Then I’ll get on my knees and pray

We don’t get fooled again.

The Who, Won’t Get Fooled Again

For most of history we had an excuse. Emperors, pharaohs, czars, kings, queens, sultans, sheiks, they descended on us via peremptory power structures and the vagaries of genetics. If the king was a warmongering dolt or half-mad egomaniac, it wasn’t our, the people’s, fault. The best we could do was keep our heads down and suffer as God almighty seemed to want us to. Occasionally there would be regime change, a new family of dolts and psychotics in charge, but for the mud-dwellers of the 99%, life was largely a cowering slog through the nether regions of obedience.

American democracy was supposed to change all that. No more twits or hysterics ruling over us, no more beef-fed murderers in ermine robes; we would choose for ourselves, a system that assumes some skill for discernment on the part of the chooser. Rare is the candidate for high office who announces he intends to screw the common folk. Policy is always put forth in the name of the greater good, to be judged as better or worse, sound or flawed based on reasoned analysis and experience, but beyond policy a more instinctive, earthier judgment is taking place about truth, character, authenticity, all in search of the straight talker who means what he says and intends to carry through. Americans care a lot about authenticity, rightly so. Every election is a quest for the genuine article. This is precisely what makes the long con of American politics such a rich and mystifying study.

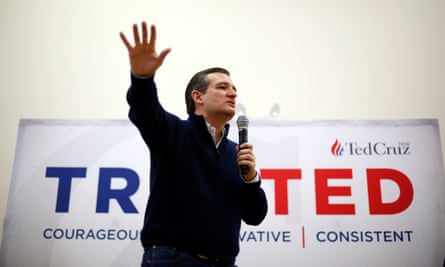

As Trump, Cruz, Clinton, Sanders, and the rest of the 2016 crew tackle the snows and insults of February in pursuit of votes, all the theatrics of authenticity are on display. The furrowed brows. The throbbing voices. The feel-your-pain hugs. Then they get on their campaign buses and move on to the next town. Americans are a famously skeptical people, but in the gyms of Iowa, the Rotary Clubs of South Carolina and all the coffee shops and civic halls to come, our perennial gullibility is there for the plucking.

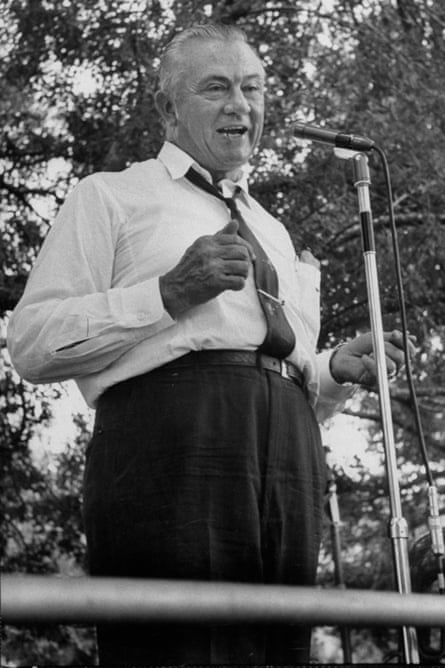

Let the record reflect: the American people are a bunch of suckers. “Weapons of mass destruction.” “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.” “Read my lips.” “I am not a crook.” “We still seek no wider war.” And these whoppers are merely a sampling from a handful of recent presidents. To strike the broad pure vein of American credulity one need dig only a bit to turn up such gems as Wilbert Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel of Fort Worth, Texas, a Depression-era salesman for the Burrus Mill and Elevator Company, producer of Light Crust Flour. In the early 30s, O’Daniel began hosting a radio show featuring the soon-to-be famous Bob Wills and the Light Crust Doughboys, though O’Daniel’s soothing, fatherly voice and easily digestible patter quickly became the real draw of the show. At 12.30 each weekday the broadcast opened with a country matron’s request to “please pass the biscuits, Pappy”. For the next 15 minutes, listeners – many of them housewives taking a midday break – were treated to twangy renditions of gospel and hillbilly tunes, interspersed with Pappy reading scripture, ad copy for Light Crust Flour, sentimental poems, and tributes to motherhood, Texas heroes, and good Christian living. His popularity grew to the point that he left Burrus Mill and started his own company, Hillbilly Flour, and began blasting his show over the 100,000 watts of XEPN, a pirate radio station across the border in Mexico.

Flour sales boomed, and Pappy himself was a star, the biggest mass-media celebrity in the south-west and a man with his eye on the next big thing. On the regular Hillbilly Flour program of 1 May 1938, he announced that as the result of a letter-writing campaign from thousands of listeners, he would bow to popular demand and run for governor. His platform consisted of the Ten Commandments, tax reform and a guaranteed pension of $30 a month to every Texan over the age of 65. His campaign theme was Pass the Biscuits, Pappy, his motto the Golden Rule. He avowed that his business experience would enable him to manage state government in a businesslike manner, and with his wife, three kids, and the Hillbilly Band (Wills had left years ago, disgusted with Pappy’s skinflint ways), the radio star began a barnstorming tour across Texas.

The effect was electric. O’Daniel had what would later be known as “name recognition”; everyone had heard, or at least heard of, Pappy. Crowds of 20,000 or more turned out for his rallies, and more than once mobs of fans forced his caravan to an unscheduled stop so they could hear the “common citizen’s candidate” rail on professional politicians, recite scripture, and plug Hillbilly Flour. An evangelical fervor was present from the start, fanned by the candidate’s Christian oratory and old-timey gospel music. The prominent Baptist minister J Frank Norris compared Pappy to Moses, predicting he would lead the country back to its Christian roots. As one historian wrote:

The O’Daniel rallies appealed to the same deep human instinct and provided the same emotional outlets which the camp meeting formerly offered. Here again was the chance to enjoy the thrill and glory of a martial movement without risking any physical bloodshed. Christ was still the hero and Satan still the enemy, but … Christ’s good, which had previously radiated from the camp-meeting preacher, was now represented by the flour-salesman. Satan’s evil, previously attached to that abhorred aristocracy which had been the pioneer’s European superior, was now found to reside in the professional politician.

When attacked by establishment candidates, O’Daniel responded with scripture: “Blessed are ye when men shall revile you and shall say all manner of evil falsely against you for My sake.” He countered objections to his Yankee origins (he was born in Ohio, reared in Kansas) with a touching story about his name: one of his uncles, a Union soldier in the civil war, had been mortally wounded, but was nursed so tenderly on his deathbed by a southern family that he sent word to his sister saying if she should ever have a son, he should be named after the great Confederate general Robert E Lee. In answer to charges of being secretly backed by big business, he replied: “How can you say I’m against the working man when I buried my daddy in overalls?”

If you’re looking for the phony in American politics, you could do worse than follow the money. In fact O’Daniel was being backed by a cabal of Texas’s richest oilmen and bankers, ultraconservatives all, and his campaign was directed by a sharp PR man out of Dallas. O’Daniel himself had grown wealthy in business and real estate, which didn’t keep him from sending his pretty daughter out at rallies with a small barrel labeled “Flour Not Pork”, appealing for desperately needed campaign funds. Sales of Hillbilly Flour doubled over the course of the campaign, and O’Daniel swept the election with more than twice the number of votes of his nearest competitor. Once in office, he began broadcasting directly from the Governor’s Mansion, pledging: “This administration is going to be me, God, and the people, thanks to the radio.”

Listening to O’Daniel’s broadcasts today is to be treated to the rankest sort of huckster charm, along with a primer in the shamelessly pandering arts of political suasion. Christian homilies, dogtrot poetry, and treacly moralizing are delivered in a smooth, slightly formal country voice that goes down like lemonade with all the tang sugared out of it. Did he believe his own schtick? He was, one longtime acquaintance said, “a born actor. He may not believe it, but he feels it at the time.” Once, his eyes tearing up as the band played The Old Rugged Cross, Pappy leaned over to a visitor and whispered: “That’s what brings ’em in, boy. That’s what really brings ’em in!” In person he was aloof and awkward, reluctant to engage the legislators with whom he had to work, even avoiding constituents who journeyed to Austin to meet their hero and tell him their troubles. But with a microphone to his lips, O’Daniel, as they say in showbiz, killed. “Son,” one longtime listener explained to her bewildered offspring, “I’ve been having breakfast with Lee O’Daniel on the radio … for the past eight years, and I know he’s a good man.”

A man who delivered pretty much zilch to the working people who adored him. In the span of four years he won four statewide elections for high office, including a 1941 special election for the US Senate in which he beat a young congressman named Lyndon Johnson. Even as his allegiance to big business and special interests became increasingly clear, Pappy’s rural and blue-collar base kept the faith. “Just because he’s a Christian man.” “Because he’s honest, mister, and because he ain’t no politician.” “He’s almost a preacher. He knows how to catch up with them congressmen and tell us about them.”

In the arsenal of the phony, the politics of God is one of the deadliest punches to the sweet spot of the American mind. Citizens capable of the most acute analysis in other areas of their lives – regarding finance, say, or electronics, or the infinitely complex variables of fantasy sports leagues – are reduced to blithering dupes when exposed to the Christian pitch. Something spooky happens to that excellent American mind that brought us moon landings and the silicon chip and the wonderful stuff that saves our kids from polio. No matter if the candidate has had three or four wives or fired thousands of workers or dropped biblical plagues of bombs on rice farmers and sheep herders, merely saying the magic words makes it so. Christian values. Strong for Jesus. In God we trust, and all the rest. Incantations that render large chunks of the electorate as dazed and vulnerable as pre-contact tribesmen from the deepest Amazon hearing a transistor radio for the first time.

If O’Daniel could be said to incarnate the phony as media celebrity and man of God, his colleague in the Senate, Joe McCarthy, embodied that other avatar of American phoniness, the national security bully. Even as he became a hero to many Americans for his anti-communist assaults, McCarthy had for most of his career what would now be called “high negatives”. This should come as no surprise: high negatives are the bully’s stock-in-trade.

Later it would be known as the McCarthy era, though it has other names as well. The Red Scare. The Scoundrel Time. The Time of the Toad. But early in his career McCarthy was known mainly for fighting price controls on sugar, work that earned him the nickname “The Pepsi-Cola Kid” for a $20,000 personal loan he received from a Pepsi executive. He was disliked by his fellow senators, who found him quick-tempered, insolent, and crude; the Senate press corps voted him “worst senator” one year. But he instantly became a national figure with a February 1950 Lincoln Day speech in which he claimed to “have here in my hand” a list of 205 Communist party members “working and shaping policy” in the State Department, setting off a media firestorm that surprised even McCarthy himself. The next day the number of names on his list dropped to 57, then rose to 81 and varied wildly thereafter, but McCarthy had struck a nerve. Riding high on his sudden fame, the senator embarked on a national speaking tour with the comment that he had “a sockful of shit – and knew how to use it”.

He had seized on a legitimate national security issue, and now proved to be a master at exploiting it for partisan advantage and personal gain. America was ripe for the kind of paranoia McCarthy was peddling. The Soviet Union had successfully tested a nuclear weapon the year before, and was aggressively consolidating its control over eastern Europe. Communists had triumphed in the Chinese civil war; within months of the Lincoln Day speech, North Korea would invade South Korea. The Alger Hiss-Whitaker Chambers affair was fresh in Americans’ minds, and a young Richard Nixon was making a name for himself with allegations of far-reaching communist conspiracies in the US government. McCarthy entered the scene like a blowtorch touched to a gas leak, and proceeded over the next four years to ruin the careers and reputations of scores of Americans without achieving a single arrest or indictment for espionage, much less a conviction in a court of law.

Like every phony before him and all the rest to come, McCarthy was a headline whore. Developing information, careful research, all the painstaking work of an actual investigation, these didn’t interest McCarthy or his chief counsel, Roy Cohn. The senator’s specialty was the media spectacle, the high-profile hearing or speech whose most salient characteristics were exaggeration, insult, innuendo and outright misrepresentation, all delivered in sensationally brutal style. A favorite tactic was scheduling announcements for late afternoon, when reporters would have scant time to check facts or get a response from the person accused. For their part, reporters and editors usually gave McCarthy the benefit of the doubt, respectful not only of his power but their own bottom line. The man sold newspapers. He glued eyes to the tube. He put on grand inquisitorial shows and was as reliable as a shooting war for generating good copy.

God, or at least his anointed mouthpieces here on Earth, stood firm by his side. New York’s Francis Cardinal Spellman declared: “Only the bat-blind can fail to be aware of the communist invasion.” The Rev Billy Graham, future consigliere to a succession of war-making presidents, termed communism a “tool of Satan” and pledged his support as the senator pursued nests of spies among the State Department, the White House, Voice of America, Hollywood, defense contractors, the US army, and embassy librarians. When Senator Margaret Chase Smith, Republican of Maine, and six more GOP senators called for an end to the smear tactics, McCarthy belittled his colleagues as “Snow White and the six dwarfs”. He habitually referred to the Roosevelt and Truman administrations as “20 years of treason”. When Eisenhower’s first year as president failed to deliver wholesale purges of alleged communists, McCarthy amended the catchphrase to “21 years of treason”. To oppose the senator, or even to identify oneself on the liberal side of the political mainstream, was to risk attack and condemnation in apocalyptic terms. McCarthy’s genius lay in using fear to transform honest differences over method and policy into moral absolutes, leveraging hysteria to a level of unchecked power that’s rarely been seen in American politics. Edward R Murrow, one of the few journalists willing to confront him head-on, is worth quoting at length:

[McCarthy’s] primary achievement has been in confusing the public mind as between the internal and external threats of communism. We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty … We will not walk in fear, one of another. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep in our history and our doctrine, and remember that we are not descended from fearful men … The actions of the junior senator of Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay amongst our allies abroad, and given considerable comfort to our enemies. And whose fault is that? Not really his. He didn’t create this situation of fear; he merely exploited it …

Fear, as Yoda said, and as Dick Cheney tacitly acknowledged, leads to the Dark Side. One might put a finer gloss on that and say unhinged fear is the active agent of our doom. Fear is a natural part of life. Hysterics, not necessarily so.

If 2016 is any indication, it seems fair to say that the phony, like the rich, will always be with us in American politics. Hairstyles and clothes may have changed, and the enemy goes by a different name, and technology has pushed the political message system into every crease and capillary of waking life, but the schtick remains the same. The celebrity, the man of God, and the national security bully are still at it, trying to separate us from our brains and our better angels. So the antidote might go something like this: hang on to our brains. Consult regularly with our better angels. And Pappy can keep his damn biscuits, thank you.

Ben Fountain, author of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, is writing a series of 2016 election articles for the Guardian

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion