Like all of the leading Republican presidential contenders, Ted Cruz has vowed to pass a series of implausibly large tax cuts that would disproportionately benefit the wealthy. But is his plan so heartlessly regressive that it would actually raise taxes on the poor?

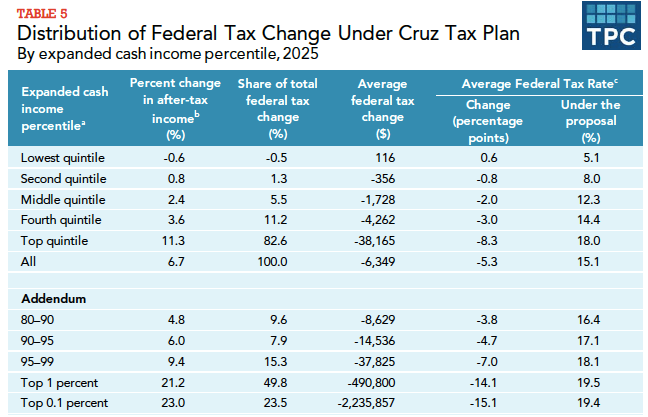

A new analysis by the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center says, indeed, it is.1 The think tank finds that by 2025, Cruz’s proposal—total cost: well more than $8 trillion over a decade—would increase the average federal tax burden for the bottom fifth of Americans by 0.6 percentage points, or $116 dollars. The top 1 percent, in contrast, would get a 14.1 percentage point cut, on average, worth $490,000. That would distinguish Cruz’s framework from the proposals put forth by Jeb Bush, Donald Trump, and Marco Rubio, which at least have the decency to offer pretty much everyone a tax cut while handing an especially large windfall to the rich.

Tax Policy Center

However, other analysts have reached different conclusions about the Cruz plan. The conservative Tax Foundation, for instance finds that it would actually raise after-tax incomes among the bottom 20 percent.

Why the discrepancy? It’s a little technical, but basically boils down to whether you buy some of the vaguer policy promises that Cruz has made to voters.

Cruz has never said that he wants to raise taxes on the poor. But it is a potential side effect of the highly regressive overhaul he’s proposed. The Texas senator plans to eliminate a whole host of taxes—including the corporate income tax, the payroll taxes that fund Social Security and Medicare, and the estate tax—while setting a flat income tax rate of 10 percent. To make up for some of that lost revenue, Cruz would then introduce a 16 percent “business flat tax,” which, branding aside, is really just a variation on what the rest of the world calls a value-added tax, or a VAT.2

The key thing to know about a VAT is that it doesn’t just hit business profits; it taxes payrolls as well. And at 16 percent, Cruz’s VAT is actually steeper than the current U.S. payroll tax. The Tax Policy Center assumes that cost will get passed on to workers in the form of lower wages. And since the poor typically don’t pay federal income tax, they won’t benefit from Cruz’s rate cuts. Hence, their overall tax burden will rise. Of course, it’s possible that instead of cutting their employees’ take-home pay, companies will pass the cost of the VAT onto customers. But in that case, the bump in consumer prices would eat away at Americans’ purchasing power and, adjusted for inflation, wages would still fall. And at the end of the day, the poor would still end up worse off.

Now here’s where things get a little ambiguous. Theoretically, Cruz has a proposal to deal with all these issues. The candidate says he wants to “expand” and “modernize” the Earned Income Tax Credit, which boosts after-tax earnings for low-wage workers, and could offset the the VAT’s erosive effect on their wages. Unfortunately, the public version of Cruz’s tax plan doesn’t offer any further detail, so the Tax Policy Center assumes he won’t actually increase the credit. The Tax Foundation, on the other hand, says Cruz is going to boost the EITC by 20 percent, which would more than make up for the VAT.

Who to believe? On this narrow point, I might actually go with the Tax Foundation, since it has a fairly decent working relationship with the Republican candidates, and the Cruz campaign may have offered it more in the way of specifics.

But in some ways, that’s missing the forest for the trees. In the end, Cruz is proposing a multitrillion-dollar rejiggering of the entire U.S. tax system that, if it falls short on the dubious promise of delivering a staggering surge of economic growth, would have barely anything to offer society’s neediest, and could leave them marginally worse off. The fact that we even have to discuss whether a major presidential candidate might actually hike taxes on the poor is horrifying on its own.

1Some conservatives will argue that TPC leans liberal—which is accurate insofar as, unlike more conservative think tanks, its analyses don’t assume that tax cuts will unleash a torrent of new economic growth. However, that assumption is also basically true to what the empirical literature tells us.

2 That’s calculated on a tax-inclusive basis—so if a blender cost $119, $19 would go to tax. If you look at it on a tax-exclusive basis (which is how most people think about sales taxes), it’s a 19 percent rate (a $19 tax on a $100 blender). But we don’t need to dive that deep into the weeds.

3The money a company earns in profit and spends on wages are considered its economic “value-add,” hence “value-added tax.”