The Fukushima nuclear disaster occurred almost five years ago in March 2011. It is the largest event of its sort since Chernobyl, which occurred 25 years earlier. The accident was triggered by a tsunami and earthquake that led to a meltdown at the plant. During this event, large amounts of radioactive materials were released into the atmosphere. Fukushima Daiichi continued to leak radioactive materials into the ground and nearby ocean in the following months.

Following the accident, concerns surfaced regarding both agricultural products from the region and the fish caught in nearby waters. In response, the Japanese government began intensively monitoring γ-emitting radioisotopes to prevent highly contaminated foods from reaching the market. The two main radioisotopes released during the accident, 134Cs and 137Cs, exhibit half-lives of approximately two and 30 years, respectively. So a large amount of the radiocesium released during the accident is still around.

Recently, a team of researchers has re-examined aquatic food contamination data in order to get a better picture of food safety.

Measurement challenges

The radioisotope contamination data for aquatic food is very difficult to interpret. The detection limit depends on the measurement conditions; it can be defined as the concentration that is within three standard deviations of the instrumentation counting error. When the level of radioactive material is below the detection limit, the data is labeled Not Detected (N.D.), but that doesn't mean it's radiation free. This results in a bias against samples containing low concentrations of radioisotopes. In some cases, all measurements from a specified region have been labeled N.D., suggesting that they may have been scanned with hardware that isn't very sensitive.

To deal with this, the researchers started with data reported monthly by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) on the radioisotope contamination in foods between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2015. Using this information, the team developed a statistical analysis to quantify contamination risk for food based on spatial and temporal information. This model allowed them to fill in the missing data caused by issues with the detection limits that result in an N.D. label.

The team's analysis indicated that the present contamination can be attributed to the Fukushima nuclear accident, and it is minimally influenced by previous nuclear accidents such as Chernobyl. Their analysis also indicated that the risk of radiocesium contamination near Fukushima has steadily decreased since April 2011.

Spatial and species impacts

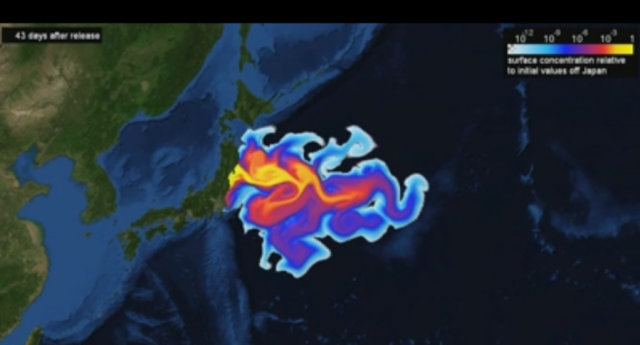

The team explored how location influenced the risk of radioactive contamination. Not surprisingly, they found that the risk of contamination of radioactive materials is highest in Fukushima itself, and contamination risk decreases as you move away from the site. The regions south of Fukushima also tended to have higher levels of contamination than the northern regions. This is likely to have been caused by higher radioactive deposition from the radioactive plume around the time of the accident.

They also explored how differences among aquatic species influenced the risk of radioactive contamination. In line with previous studies, the team found that the contamination risk for bottomfeeders is highest in marine fish and is much higher than for fish that live away from the floor and the shore. Analysis indicates that the contamination of marine fish has rapidly dispersed even at the bottom of the sea since the accident.

The scientists found that the freshwater species had higher contamination risks. This could be attributed to differences in osmoregulation systems of freshwater and marine fish, which cope with exposure to different levels of salts. Due to their osmoregulation system, freshwater fish hang on to radiocesium for longer than marine fish do.

Species-specific contamination

The team analyzed the contamination risks for a representative group of fish in Fukushima. Their results were in line with their own work and previous studies, indicating that the contamination risks are relatively high for freshwater fish, freshwater crustaceans, and fish that migrate between the oceans and freshwater.

This doesn't have as much impact on food safety as it might seem. At this point, the overall risk of contamination for most aquatic food is low. The freshwater fish used for food in Japan are typically cultured, not wild caught—the radiocesium concentrations of cultured fish are usually low. But the contamination could be a major problem for recreational fisheries and tourism. Strict regulations restrict or prohibit even leisure fishing if a fish is caught with a concentration of radioactive contamination exceeding 100 becquerel/kg.

This analysis reveals that many data points that were labeled "Not Detected" actually did have very low contamination levels associated with them. Lowering the detection limits would help increase sensitivity to better monitor contamination. Accordingly, the team recommends a revision in the detection limits of the current monitoring program. Finally, this investigation demonstrates that this statistical methodology could be leveraged to help ensure a quick and effective recovery from the Fukushima accident.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 2016. DOI; 10.1073/pnas.1519792113 (About DOIs).

reader comments

71