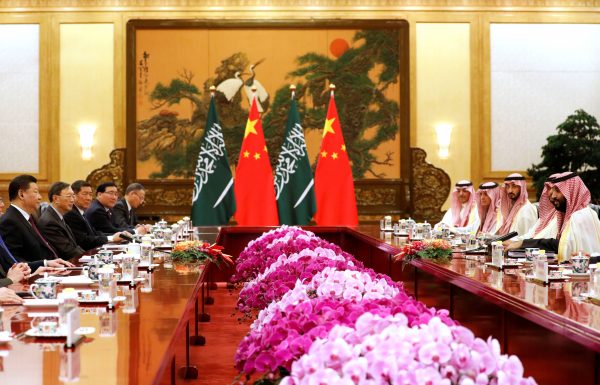

Some saw this as a reflection of worsening US–Saudi ties in the wake of the Jamal Khashoggi murder in 2018. It is actually part of a growing bilateral relationship between China and Saudi Arabia that has been deepening since diplomatic relations began in 1990. This in turn is part of China’s growing relations with the other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

For the Gulf monarchies, dense relations with extra-regional powers are an important pillar of their foreign and security policies. The United States has played this role since the aftermath of the Gulf War, signing defence cooperation agreements with Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and the UAE, and building upon the facilities access agreement it signed with Oman in 1980. Underwritten by the Carter Doctrine, the United States has consistently practiced a balance of power approach to the region with two goals: ensuring that no other external power is able to challenge American dominance, and that no regional state becomes strong enough to disrupt this fragile balance.

Under the US umbrella, China is taking advantage of this security guarantee to significantly deepen its regional presence. Its focus is primarily economic. As the world’s largest energy importer it is no surprise that China would see the Gulf monarchies as important trade partners. From 2000 to 2017, China–GCC trade grew from just under US$10 billion to nearly US$150 billion. But it is not as one-sided as China buying huge volumes of Gulf oil and gas. The trade relations are relatively balanced and China actually exports more to Bahrain and the UAE than it imports.

Beyond trade, the economic relationships are well-rounded, with finance and investment as the other pillars. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) into the GCC is substantial, at nearly US$90 billion between 2005 and 2018. This is important for the Gulf monarchies as they are all under pressure to create more diverse economies, and so are embarking upon massive infrastructure and construction projects. Chinese firms are especially well-positioned to take advantage of this, with a competitive approach to infrastructure development driving much of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Chinese institutions are also establishing investment funds with Gulf sovereign wealth funds to finance projects related to Gulf diversification programs and the BRI. So far, the UAE and Qatar have created joint funds and Saudi Arabia and Kuwait are reportedly at the planning stage.

Both the UAE and Qatar have also set up renminbi currency swaps to support the many projects Chinese firms are undertaking in the region. The UAE’s renminbi clearance house was used to clear over US$7 billion in transactions in 2018 alone. With Chinese banks building-up their regional presence, mostly in Dubai, expect the renminbi to be used more in China–GCC trade.

Many point to the economic nature of these relationships as a sign of inherent weakness. Without a corresponding security arrangement, China will never be considered a top-tier power in the Gulf. In this view, it is an opportunistic free-rider taking economic advantage of a loophole that the US security architecture provides. Unless it is willing to protect its trade and investments with bases and boots on the ground, China will not be taken seriously in the Gulf.

This view misses the point of China’s approach. For one, there have been slow and largely quiet steps toward a larger security role. Recent years have seen joint military training exercises, increased high-level meetings between defence officials, port calls from the People’s Liberation Army Navy and increasingly important weapons sales.

While none of this is in the same ballpark as the US security role, it is not meant to be — a larger Chinese security presence would most likely be perceived as a challenge in Washington. There is no point in antagonising the United States needlessly in the Gulf and Chinese leaders seem well aware of this.

More importantly, China is not ready to be seen as a major military power in the Middle East. While the BRI is expanding its power and influence, it is not yet militarily on a comparable level to the United States. So Beijing has used its economic presence as a means of deepening relations in a strategically important region while at the same time working to not be perceived as disruptive or overly ambitious.

It is hedging in the Gulf, building strong ties with every state in the region at a time when the US commitment to the Middle East is in question. The GCC is especially receptive to this attention from China, keen to deepen their pool of extra-regional powers with an interest in Gulf stability. As the BRI continues to take shape in the Middle East, expect to see greater China–GCC cooperation.

Jonathan Fulton is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Zayed University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates and author of China’s Relations with the Gulf Monarchies.