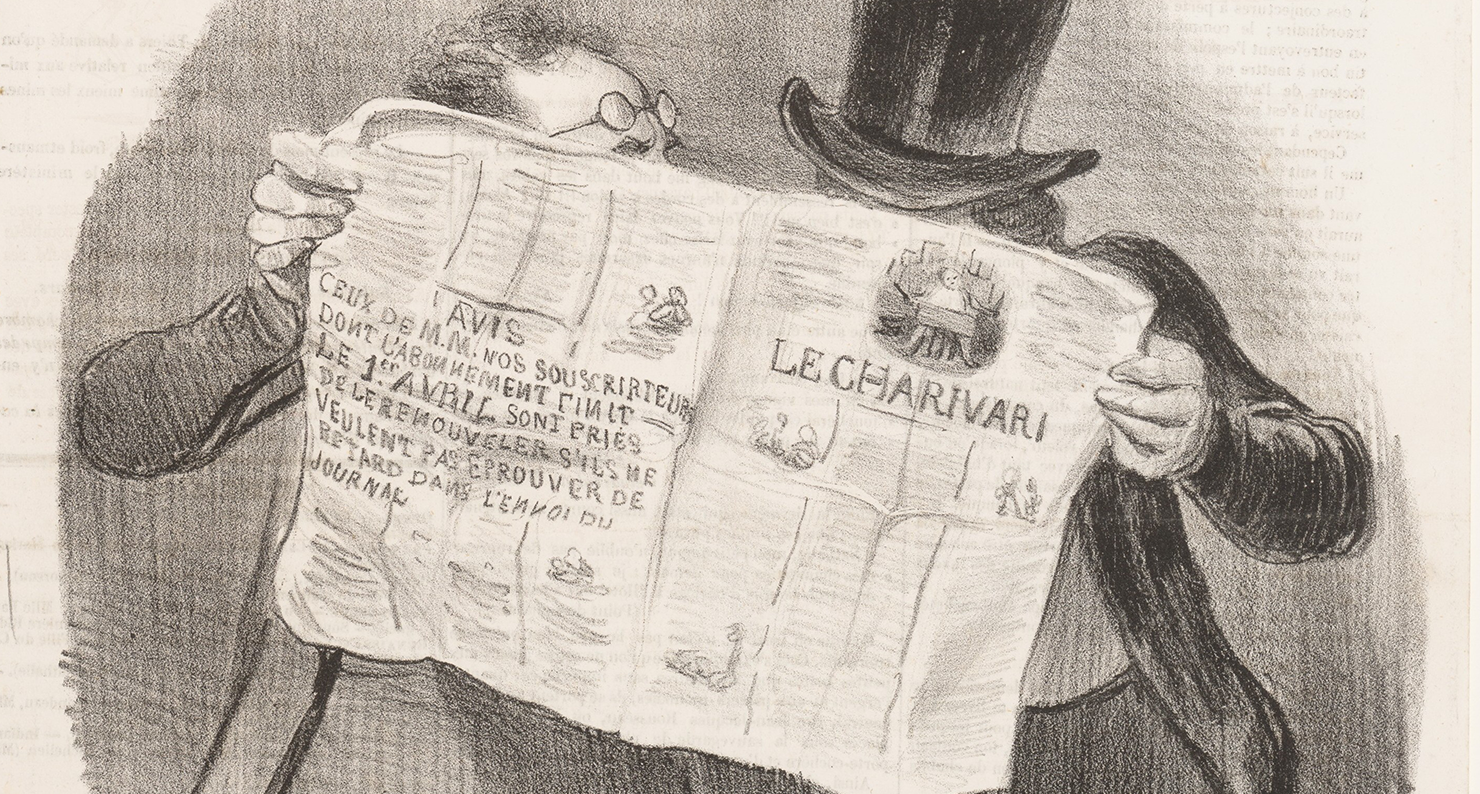

Advice to Subscribers, by Honoré Daumier, 1840. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Grace M. Pugh, 1985.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

I really look with commiseration over the great body of my fellow citizens, who, reading newspapers, live and die in the belief that they have known something of what has been passing in the world in their time.

—Thomas Jefferson

Wherever news is sold these days—online and on camera, in print or en blog—the product comes wrapped in the claim “Ours is real! Theirs is fake!” Shills and scolds on all sides of the story line or tweet, chief among them the president of the United States but also CNN and Fox, the New York Times and the Drudge Report, accuse one another of trampling out the vintage where the grapes of truth are stored. Op-ed pundits in all styles of wizard hat dress up the commotion in the trappings of apocalypse, announce the death of America’s democracy, see everywhere on the horizon fact-free dictators slouching toward Facebook to be born.

The soundings of alarm are more alarming than the sound and fury they deplore. More alarming because the keepers of the nation’s conscience apparently have forgotten, or maybe never were so informed, that news doesn’t grow on trees. All news is fake in the elementary sense of fabricated artifact, like Diet Pepsi and Ivory soap. Not what happened yesterday; a story about what happened yesterday.

The Trojan horse was fake news; so was the birth of Christ and the press release declaring all men created equal. Fake news is the stuff with which Plato made his dream of The Republic. Children of the city must believe the “noble falsehood” the rulers of the city teach them to believe in order to maintain the health and well-being of the body politic. Whether the story is true or false matters less than the children not forgetting their duty to believe it. The noble falsehood is the society’s self-preserving myth.

President Trump’s falsehoods don’t qualify as noble because they aren’t embedded in the self-preserving myth of the American democracy—government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth. The president governs by and for his imperishable self, the health and well-being of the society to be preserved in the fragrance of Empire and Success, his signature men’s colognes.

Journalists of any and all description (analog and digital, mainstream and disruptive) rely on the self-promoting myth of a free and fearless press, champion of the people, honor and duty bound to speak truth to power, deliver all the news that’s fit to print. Their noble falsehood never has commanded or deserved belief among children of the city old enough to know their baby brother wasn’t delivered by a stork. Newspapers serve at the pleasure of whatever news is fit to sell, governed by the political and commercial interest of their sponsors. The result is a product described in 1941 by Dorothy L. Sayers, British novelist and playwright, as a mash-up of fixed opinion and temporary fact, a “smear of unreality…spread over the whole newspaper page, from reports of public affairs down to the most casual items of daily gossip.” Sayers lists some of the standard operating procedures, among them sensational headlines, false emphasis, suppression of context, garbling, random and gratuitous invention, flat suppression, and deliberate miracle mongering. The tricks of the trade were as ably deployed in newspapers of the 1790s controlled by John Adams and Thomas Jefferson as in newspapers in the 1890s commanded by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst.

But in the long, dark, and lonely night before the dawn of television, readers of the printed press understood they were playing with loaded dice. They expected messages to show up on, at, or under the table armed with both a concealed and open lie. They didn’t take offense or show cause for alarm. They looked to newspapers for entertainment, not for a civics lesson, and it was generally understood by readers both literate and not that the making sense of whatever reality a newspaper chose to advertise required effort on the part of citizens seeking to be well-informed. Not much effort, but at least the knowing how and what else to read (periodicals, other newspapers, possibly a book) as well as the willingness to bear the risk of thinking for oneself.

America never has produced such readers in large and commercial quantity, but prior to the advent of television, there were enough of them in red states as well as blue to preserve the myth of a democratic society founded on the meaning and value of words. The electronic media shift the telling of the noble story to images of wealth and power signifying nothing other than their own contrived and disposable magnificence. Everything on television is advertising, all advertising the voice of money talking to money, the mounting of predatory spiels prioritized to sanction ignorance and preserve privilege.

Want to read more? The History of Fake News special issue is available for purchase here and features writing by Virginia Woolf, Mark Twain, Renata Adler, Plato, and more.