The Cities That Never Existed

What if the urban visions of famous architects and planners had actually been built?

It was a bright summer morning in 1940. As Paris emptied of people, a single panic-stricken thought swept through the chaos of the crowds: Il y a péril en la demeure—there is danger in delay. The thief thought so too, though in a different sense. He watched as the families scrambled onto trains bound for no particular destination, just anywhere south of the capital, out of reach of the advancing Germans. He left the station by another exit, the secret pocket in the lining of his jacket already full. Closing his eyes briefly, he felt the sun on his face. Then he headed for the river and the rows of cross-shaped, residential-tower blocks on the horizon.

He passed over the vast green spaces between the towers. He was old enough to remember when this area had been called Le Marais. It had been full of ramshackle old shopfronts, Russian accents, synagogues. All gone now, bulldozed and dynamited, replaced by Le Corbusier’s monumental modernist vision of concrete, steel, and glass. They’d even moved some of the centuries-old churches and palaces elsewhere, among them the Church of Saint-Gervais-et-Saint-Protais and the Hôtel de Beauvais. He paused on a bridge above a highway; one side was stuck fast with traffic and furious terrified runaways, the other deserted. The sound of horns, shouts, and engines faded as he approached the building. The lobby was empty. The corridors were deserted.

He took the elevator to the top. Toys were scattered around the rooftop kindergarten. The swimming pool was empty. He could see, far below, an airdrome already abandoned, littered with passenger stairs. He thought he could hear bombardments in the distance. For one night, he had his pick of virtually anywhere and anything in the towers. He was a king in a disintegrating republic.

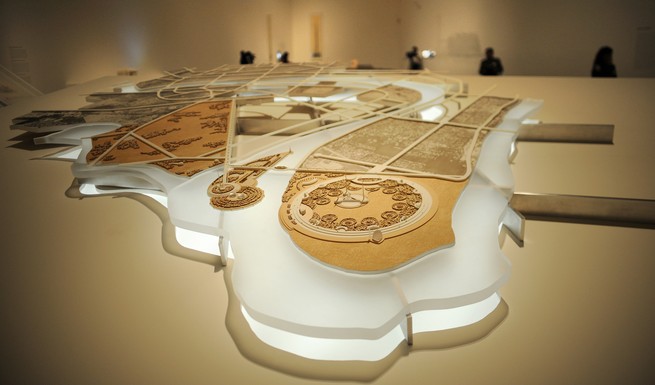

These things both did and didn’t happen. Paris would indeed fall to invading German forces on June 14, 1940, and thieves surely did prowl that dark confusion. But Le Corbusier’s proposal to replace the city’s central districts with tracts of high-rise towers was never realized. Those visions of the early 1920s, known as Ville Contemporaine, Plan Voisin, and Ville Radieuse slipped into an alternate time line, one our version of Paris, and the world, will never see.

Citizens would do well to revisit these unbuilt cities, to let their alternate histories roll around in the head. People might return to unbuilt architecture as inspiration for the future, but unrealized cities offer more than just old ideas renewed. They also remind people of how the world, so solid and certain to us now, could easily have been so different.

Though unbuilt, Le Corbusier’s proposals would go on to influence others. They inspired Lúcio Costa, Roberto Burle Marx, and Oscar Niemeyer’s urban plan for Brasília, a planned capital that seems refined to the point of being nearly inhuman. By contrast, in 1932 Frank Lloyd Wright designed his unbuilt suburban utopia, Broadacre City, in a disgusted response to Le Corbusier’s proposed Parisian grid (he called them “feudal towers ... with no life in them”).

From the beginning, Le Corbusier knew his original plan to house 3 million Parisians would have a polarizing effect. “The shock of surprise caused rage in some quarters and enthusiasm in others,” he noted. His projects contained good ideas and bad. The prospect of bulldozing vernacular architecture, obliterating streets, and displacing communities were rightly derided as philistine. But Le Corbusier’s stated intentions always offered what he saw as healthy solutions to pressing questions of the time, from slums to urban sprawl, traffic to population density. Shoddy imitators proceeded to desecrate the concept of living in the sky. Others, ignoring his careful consideration of zoning, destroy urban tracts without long-term plans. But some elements of Le Corbusier’s plans have aged well—his emphasis on green spaces as “the lungs of the city”; a serviced apartments approach (with childcare, laundry, exercise, and cuisine provided in-house) that is now omnipresent in luxury if not egalitarian circles; his romanticism of aesthetics, and his obsession with access to light and air: “As twilight falls, the glass skyscrapers seem to flame.” In their haste to condemn and forget the failings of the Plan Voisin and its kin, urbanists risk throwing away the lessons it offers in how to live rationally and even poetically.

Historians sometimes bemoan hypotheticals as entertaining, but indulgent, diversions. Uncovering objective truths seems paramount for those studying the past, even if humans are subjective creatures. And considering what might have happened is notoriously slippery. Change one detail and, via the butterfly effect, all manner of subsequent ones also alter. Yet despite the dangers of dreaming of what might have been, people do so anyway, partly because the storytelling aspect to history is an art as well as a science.

It is also partly because there were many moments when everything came close to being completely different. History is clotted with contingency, and those accidents reverberate through the built environment. In June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria narrowly escaped assassination in Sarajevo, only for his chauffeur to take a wrong turn and end up on a street where another would-be assassin, Gavrilo Princip, happened to be standing (though apocryphal, he is said to have been eating a sandwich at Moritz Schiller’s delicatessen). A plaque now marks the spot, near the Latin Bridge, where history’s tracks shifted dramatically toward World War.

Where the Gasteig now stands in Munich, there was once a beerhall called the Bürgerbräukeller. A disgruntled leftist carpenter by the name of Georg Elser had placed a time-bomb there, inside a pillar, in anticipation of a speech by Adolf Hitler. The Nazi leader cut his speech short unexpectedly, due to his flight being canceled by fog, and left early for a train. The bomb went off moments later, killing seven and instilling a belief in Hitler that he had been protected by divine Providence.

When reviewing memorials to the victims of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it’s worth remembering that the ancient town of Kokura was spared the blast, due to poor weather and visibility, while Kyoto was reputedly saved due to the fact that the U.S. Secretary for War, Henry L. Stimson, had honeymooned there. Parallel worlds are so close, so often, it’s remarkable that their shadows go unnoticed.

It is May 2, 1958. King Faisal II of Iraq is celebrating his 23rd birthday at the nation’s consulate in Manhattan with a special event: an unveiling of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Plan for Greater Baghdad. The young monarch had invited leading international architects of the day (including Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Alvar Aalto) to contribute to his new vision of society.

Wright’s vision began with an opera house and ended with an incredibly ambitious concept, repeatedly geometrically referencing the spiral of the Great Mosque of Samarra and the famed round city of Baghdad from the days of the Abbasid Caliphate. It would be based around Pig Island in the Tigris, which he’d spotted as his plane was coming in to land.

The king gave his approval. Inspired by a childhood love of One Thousand and One Nights, the American architect came up with an orientalist, but not ahistorical, fantasia of waterfalls, bazaars, and museums, with statues of Harun al-Rashid and Aladdin.

Wright’s Greater Baghdad could have had numerous outcomes. In one, its university becomes a modern-day House of Wisdom, and the Hashemites are revived as benevolent enlightened leaders. In another, it becomes a proto-Dubai, buoyed up by oil and foreign investment. But a broader context is crucial. The island Wright picked out was prone to flooding, rendering the site unstable from the beginning. At the same time, politics in the region was becoming increasingly turbulent. Faisal’s grand vision could well have been a derided, expensive folly or an extravagantly derelict post-Olympics-style liminal space ignored by most Baghdadis. Equally, it could have become the site for public protest or even, with its planned communications centers, a target in the coup d’état conspiracies that were fomenting at the time.

But Wright’s Plan for Greater Baghdad would never be built. Faisal’s birthday celebrations would be his last. A cabal within the Iraqi military turned against him, seizing key installations and surrounding the palace. The royal family made it out into the gardens, where—accounts of the specific details differ—they were reportedly gunned down. The conspirators would not live or rule for very long; most would die by sabotage and assassination. They’d set into motion a series of events that would bring the Ba’athists to power during the bloody Ramadan Revolution of 1963 and eventually the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein.

It is impossible to study the almost-Baghdad of Frank Lloyd Wright without laden knowledge of the Baghdad that followed, from the Swords of Qādisīyah to the Green Zone—and their attendant costs in human lives. To consider lost ages as golden ones, whether in the past or in an unrealized untested retrofuture, is a form of romanticism and escape that remains understandably tempting for Iraqis given what they have endured.

Instead, people should occupy unbuilt cities, even if just in the mind, and dig deep into their implications. We can imagine what it would be like to drive through or reside within the sequence of glass pyramids in Stanley Tigerman’s Instant City (1965), where symbols of power no longer enshrine pharaohs but the supremacy of the automobile.

We can wonder whether King Camp Gillette’s metropolis on the Niagara Falls (1894), at once modern (with the latest in telecommunications, elevators, and hydroelectric power) and quaint (an exterior of porcelain, apartments fitted with parlours and music rooms), would have become a roaring success or a series of dilapidated vertical mega-slums. For a man who made his fortune selling safety razors, Gillette had a remarkably radical view of the future, “No system can ever be a perfect system, and free from incentive for crime, until money and all representative value of material is swept from the face of the Earth.”

We can look at numerous encased cities like Seward’s Success (1968) with their climate-controlled environments and kitsch sci-fi monorails, and wonder at the psychological effects of living under a dome with thousands of others in Arctic or Antarctic conditions.

However much designers and citizens alike might wish or assume it, architecture does not remain aloof from wider social and political developments. Would Le Corbusier’s plan to turn Algiers into a linear city have reduced the pressure that burst from the Casbah and culminated in the Algerian Revolution or caused it to explode further and faster? Would Tatlin’s Tower, with its revolving chambers, loudspeakers and projections, be a long-malfunctioned post-Soviet ruin now, in dire need of repair and restoration by those nostalgic for what the future used to be? What would have happened to Iofan’s Palace of the Soviets with its colossal figure of Lenin (halted at the onset of the German invasion) after the fall of Communism and the iconoclasm that accompanied it?

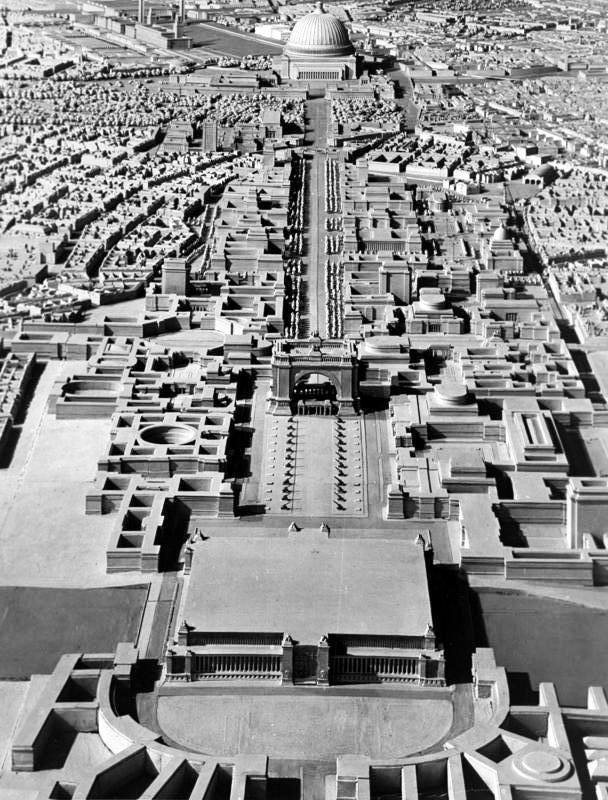

Or consider that there is no Moscow at all anymore. What was once the capital lies under a vast reservoir. Its inhabitants were murdered or deported as slave labor under the victorious Third Reich’s plans. The Baltic, Crimea, the Volga, and the Middle Eastern oilfields are in German hands. Bolshevism no longer exists bar fractured forces east of the Urals and in the Caucasus. Hitler and Speer’s architectural plans have been realized. Berlin is replaced by Germania, declaring itself the “World Capital,” with a Volkshalle so large clouds form inside it, and a Triumphal Arch that could swallow up Paris’ Arc de Triomphe. Linz builds the grandest collection of art on the earth at the Führermuseum. The Deutsches Stadion in Nuremberg accommodates over 400,000 people. Huge, dread towers to the Nazi dead, based on the Tannenberg Memorial, rise across Europe. Yet the grandeur of Germania is capsizing under unstable soil, foundations slowly buckling, cracks appearing in walls; just as the sinking prototype Schwerbelastungskörper suggested.

Utopian/dystopian plans may envisage a world where they build on blank spaces, where they can somehow start again without memory or consequence, but the past cannot easily be erased. The millions of murdered Jews, Slavs, Roma, and homosexuals, some worked to death excavating building materials for Germania, may have been officially written out of Nazi history but the Earth would have remembered them, like a secret waiting to be discovered. There is a chilling moment in Albert Speer’s Inside the Third Reich when, amidst his fantastical plans and moral acrobatics, he talks to his friend, the SS Reichsführer Karl Hanke. “Sitting in the green leather easy chair in my office, he seemed confused and spoke falteringly, with many breaks,” Speer writes. “He advised me never to accept an invitation to inspect a concentration camp in upper Silesia. Never, under any circumstances. He had seen something there which he was not permitted to describe and moreover could not describe.”

This moment underlines the vital importance of looking at what happened, at what could have happened, and what could yet come to pass if we follow plans blindly or without formulating our own. “Other worlds are possible” seems an attractive proposition, but those alternate futures might be dreams, or they might be nightmares, depending on how people act in the here and now.