Workers wearing personal protective equipment bury bodies in a trench on Hart Island, Thursday, April 9, 2020, in the Bronx borough of New York. On Thursday, New York City’s medical examiner confirmed that the city has shortened the amount of time it will hold on to remains to 14 days from 30 days before they will be transferred for temporary internment at a City Cemetery. Earlier in the week, Mayor Bill DeBlasio said that officials have explored the possibility of temporary burials on Hart Island, a strip of land in Long Island Sound that has long served as the city’s potter’s field. John Minchillo, AP

A Catholic priest in New Orleans slipped on a surgical gown and face mask and performed last rites on a woman dying in a hospital alone.

A New York City doctor delivered messages from family members to patients taking their final breaths on ventilators.

An intensive care nurse in Chicago scribbled the name of a coronavirus survivor on a Post-it Note and stuck it on a dry erase board in the unit–a small memorial to a rare victory in an otherwise grim week.

The second week of April marked the deadliest week since the coronavirus pandemic arrived in the United States three months ago. According to numbers tracked by USA TODAY, 12,056 Americans succumbed to COVID-19 in that seven-day span.

One day registered a new deadly high of 1,973 deaths, only to be surpassed two days later, when the death toll jumped to 2,108. By the end of the week, the U.S. had eclipsed Italy with the most reported coronavirus deaths in the world, with 20,608 since the outbreak began.

The death toll was highest in New York, Chicago, Seattle, Detroit and New Orleans, where bodies beset hospitals and overflowed morgues. As the painful week unfolded, USA TODAY reporters interviewed relatives of the deceased, funeral directors, faith leaders, medical examiners, grief counselors, doctors, nurses and others on the front lines of the outbreak about what they witnessed from Sunday, April 5, through Saturday, April 11.

The coronavirus has now killed more Americans than the Pearl Harbor assault, the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the Iraq and Afghanistan wars – combined.

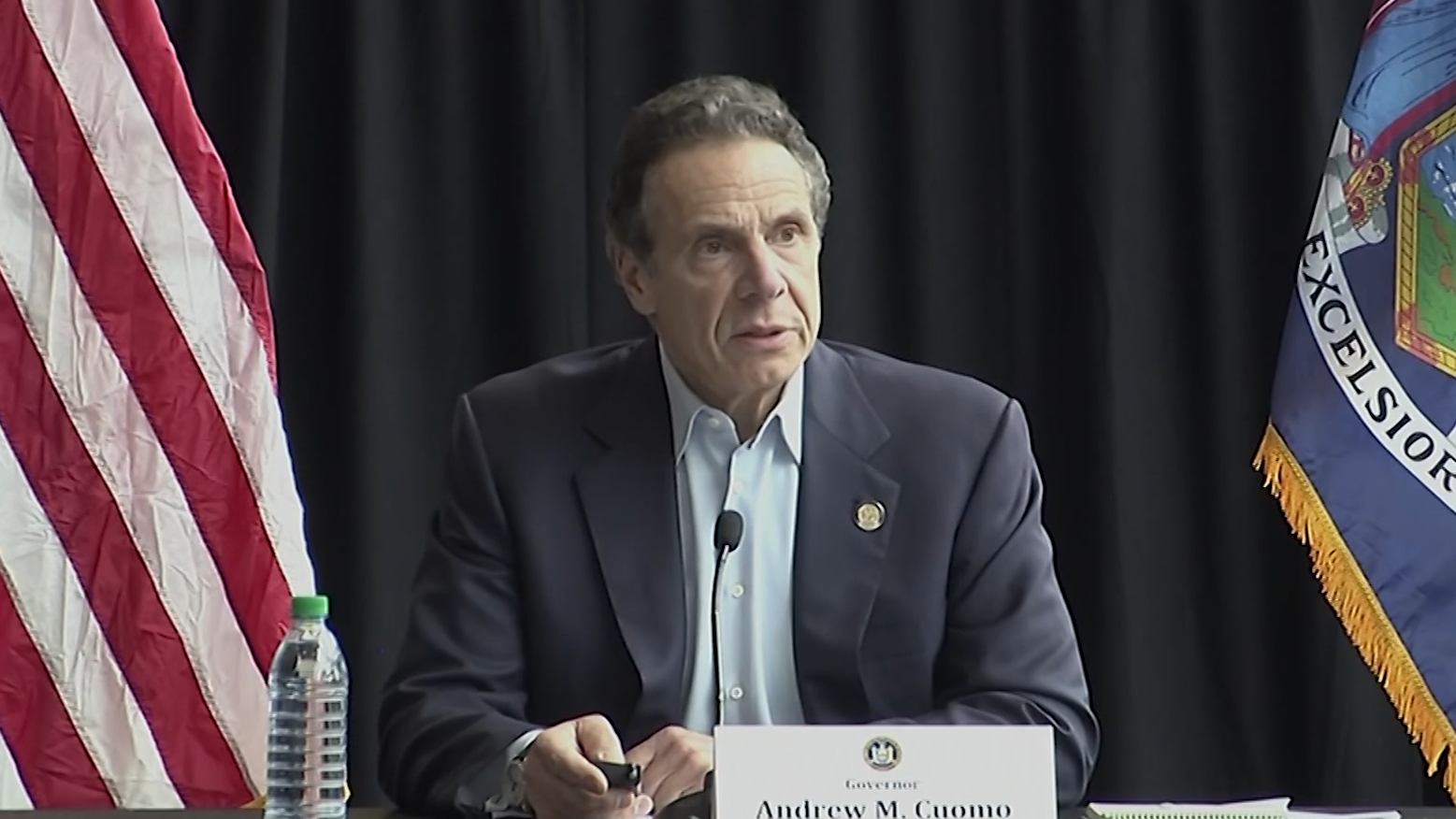

“Behind every one of those numbers is an individual,” New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said during a briefing on Tuesday, when New York reported 731 people had died from the virus. “There’s a family, there’s a mother, there’s a father, there’s a sister, there’s a brother."

COVID-19 works quickly and with lethal contagion, often forcing loved ones to die alone in hospital rooms, surrounded only by medical staff draped in protective gear and the dry rasp of ventilators.

There are also moments of hope and human triumph: neighbors stepping onto their balconies to cheer medical staff at dinnertime each evening. Homemade altars celebrating life in the face of so much death. A woman's determination to help a friend in need.

In New York, there were 6,367 deaths

Jennie Moses got a phone call. Her longtime friend Eunice Oden had cold symptoms and a hint of fever. Moses pulled out the thermometer she bought some 20 years ago and walked three blocks to her friend’s apartment in Brooklyn's Crown Heights neighborhood.

“It’s about 20 years old if you want to try,’’ Moses, 79, said to her friend. "I guess it still works.’’

They cleaned it with alcohol swabs and dried it with a paper towel. Oden put it under her tongue. It showed 100.

The next morning, Moses called to say happy birthday. Oden was turning 78, but she wasn’t feeling well. She drove a few blocks to Interfaith Medical Center, where she was admitted. She asked her friend to bring her some things.

Moses packed her mask and gloves and took the bus to the hospital. Moses was determined to get the little red bag to her friend. Tucked inside were a toothbrush, slippers, a nightgown. She waited and waited, asking nurses when she'd able to see her friend. “We don’t know," she was told.

The friends had grown closer in recent years. They attended the same church and sometimes lunched at Applebee's, often ordering salad, sometimes treating themselves to french fries.

Oden's nephew was the one who called Moses with the news: Oden was dead.

By Saturday, New York City had tallied 6,367 deaths, by far the highest in the U.S. for a metropolitan area and nearly three-fourths of the state's total of 8,650.

Moses still can’t believe her friend is among those numbers. “She was all right, always willing to help,” she said.

She regrets never saying goodbye. But God had his own plans, Moses said.

"She was just meant to be here 78 years," she said. "Her job was done. He called her in."

'Tell grandma I love her'

Of everything the virus takes, the chance to say goodbye is one of the cruelest. Dr. Susana Bejar, an internist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in Manhattan, has been delivering short messages from family members to their loved ones:

"Tell grandma I love her."

"We're thinking about you."

"We love you."

The patients are often disoriented, their brains struggling to stay alive.

“They don’t know the month or the day or the present," Bejar said. "But if you say their son’s name ... they recognize that name.”

COVID-19 patients have overrun the hospital, taking up all floors, Bejar said. Gone are the days when doctors touched a shoulder to comfort a patient, she said. Medical staff touch as little as possible.

One of the hardest things to witness is the isolation that surrounds patients in the final moments of their lives, Bejar said. One elderly woman survived being HIV-positive and years in a nursing home only to be hospitalized with the virus. She died in her hospital bed, with only Bejar at her side.

“She made it through all that only to die one Sunday night with me in a hospital," she said. “She just passed away alone to the COVID one night, and I have no family to tell.”

'I try my best not to take it in'

With her Brooklyn floral shop closed because of the outbreak, Lynn Anderson is working from home designing artificial arrangements for funerals.

Her friends and customers at funeral homes in New York are overwhelmed, she said. Some can’t take more bodies. Some are doing “direct burials,” shipping bodies from the morgue straight to the cemetery. Others have limited viewings, with families looking at loved ones through glass.

“I’m numb,’’ she said of the orders coming in. “I try my best not to take it in so much because then I won’t be able to perform my job.”

Recent orders include an arrangement of red and white flowers made of a silky material. Another will have yellow, purple and white flowers. There will be mostly roses, but there are lilies, too, and hydrangeas for fullness.

“Remember now, they can’t be choosy. They have to take what I have,’’ she said. “You can’t tell unless you go up and touch it.”

In Chicago, there were 453 deaths

On Thursday, Dr. Ponni Arunkumar, Cook County's chief medical examiner, drove 20 minutes through Chicago to a refrigerated warehouse.

The county morgue had overflowed with corpses, as had hospitals and funeral homes. The first bodies had been placed in the warehouse; many more were coming.

“We hope we don’t have to use all that capacity," she said, "but we’re prepared to.’’

As of Saturday, Illinois had reported 677 deaths, of which 453 were in Cook County, which includes Chicago.

Arunkumar sometimes springs awake in the middle of the night, thinking about the bodies.

"This is what we signed up for," she said. "We just have to carry through.”

Praying for the helpers

Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago has a strict no-visitor policy. Sometimes they make exceptions.

On Sunday, Katie Martino, a nurse in the hospital's cardiac intensive care unit, had a patient, a woman in her 60s, who was slipping fast. She led two family members wearing face masks into the room. A short time later, the woman died.

Martino finished her shift and returned home, but that death lingered. The only solace she took away was that she had been able to get the family to the woman’s bedside before it was too late.

“Thankfully, we were able to give that to them,” she said.

On the days she’s not working, she joins a neighborhood prayer group. About 10 of them stand outside their houses and pray for Martino, for a firefighter who lives on the block, and for the patients they’re treating.

Screams, howls and clapping

On Wednesday, Patrice Rosenberg watched as an anesthesia team prepared to place a coronavirus patient on a ventilator at Northwestern Memorial.

As the registered nurse in charge of that COVID-19 intensive care unit that day, she was making her rounds, checking on 20 patients and 14 nurses.

Suddenly, Rosenberg realized she didn’t know the nurse responsible for that patient.

“I looked at her ID, but she saw me,” Rosenberg said. “She busted me. I said, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t know who you are.’”

Those kinds of moments have become more frequent for Rosenberg, 29, as her hospital has converted three areas into COVID-19 intensive care units, with nurses flooding in from retirement, other departments and other hospitals to care for coronavirus patients.

Rosenberg has to learn the background of each new nurse, determine what they’re qualified for and get them up to speed on the hospital’s latest procedures for handling the pandemic.

As her 12-hour shift drew to a close, Rosenberg debriefed the nurse who would take over that night. They ran over each patient, each nurse, each batch of medications on the floor.

She got home close to 8 p.m. and prepared for her usual routine – an immediate shower, dinner and sleep. But on this day, her boyfriend made her walk out to their rooftop and listen. She heard screams, howls and clapping.

Like so many other cities around the country, people in Chicago were making noise to honor the city’s health care workers. They were celebrating her.

Post-it Notes of hope

The good days have been few and far between for Sarita Mazurowski.

Just a few weeks ago, the registered nurse spent 45 minutes watching one of the first patients die from COVID-19 at Northwestern Memorial. With his family unable to be there for their own safety, it was up to Mazurowski to hold the patient's hand and deliver their final words.

Physicians were standing outside the room, instructing her on what medications to deliver, what measures to try.

“But in the end, it was just me and him,” she said.

She was in constant contact with the man's family. They kept asking her, over and over: "Please, I know that he’s sedated, I know that he probably won’t understand, but let him know we’re thinking about him, we love him, we wish we could be there for him."

Monday started off no different. Mazurowski, 31, was in charge of a COVID-19 intensive care unit and was making her rounds when she came across a name she recognized – a woman who was one of the first three coronavirus patients to enter the hospital.

The woman had been on a ventilator for three weeks, an ominous sign.

For those patients, nurses sometimes resort to “proning” them – turning the patient onto their stomach to open up air spaces in their back. It’s rough on the patient, but it’s sometimes used when options are running out. This woman had already been proned eight or nine times.

Hospital staff called her family and told them they didn't think she was going to make it.

But as Mazurowski started talking with the nurse in charge of that woman’s care, she heard something unexpected. Nurses had been weaning the patient off the ventilator, letting her lungs take over little by little. In fact, the nurse told Mazurowski that they were going to try to remove the ventilator completely that day.

It worked.

“I couldn’t stop talking about it to my co-workers,” she said, a smile stretching across her face. “Just being like, ‘Do you remember her? She’s coming off the ventilator today.’ And then the next day, it was like, ‘Oh my God, she’s leaving the ICU, she’s doing so well.’ She may have even been able to go home. Yeah. Yeah. Just amazing.”

That day, she noticed a giant, unused dry erase board. For each patient able to come off a ventilator and transfer out of the ICU, the staff began writing their names on Post-it Notes and sticking them on the board – a celebration of life.

In Seattle, there were 282 deaths

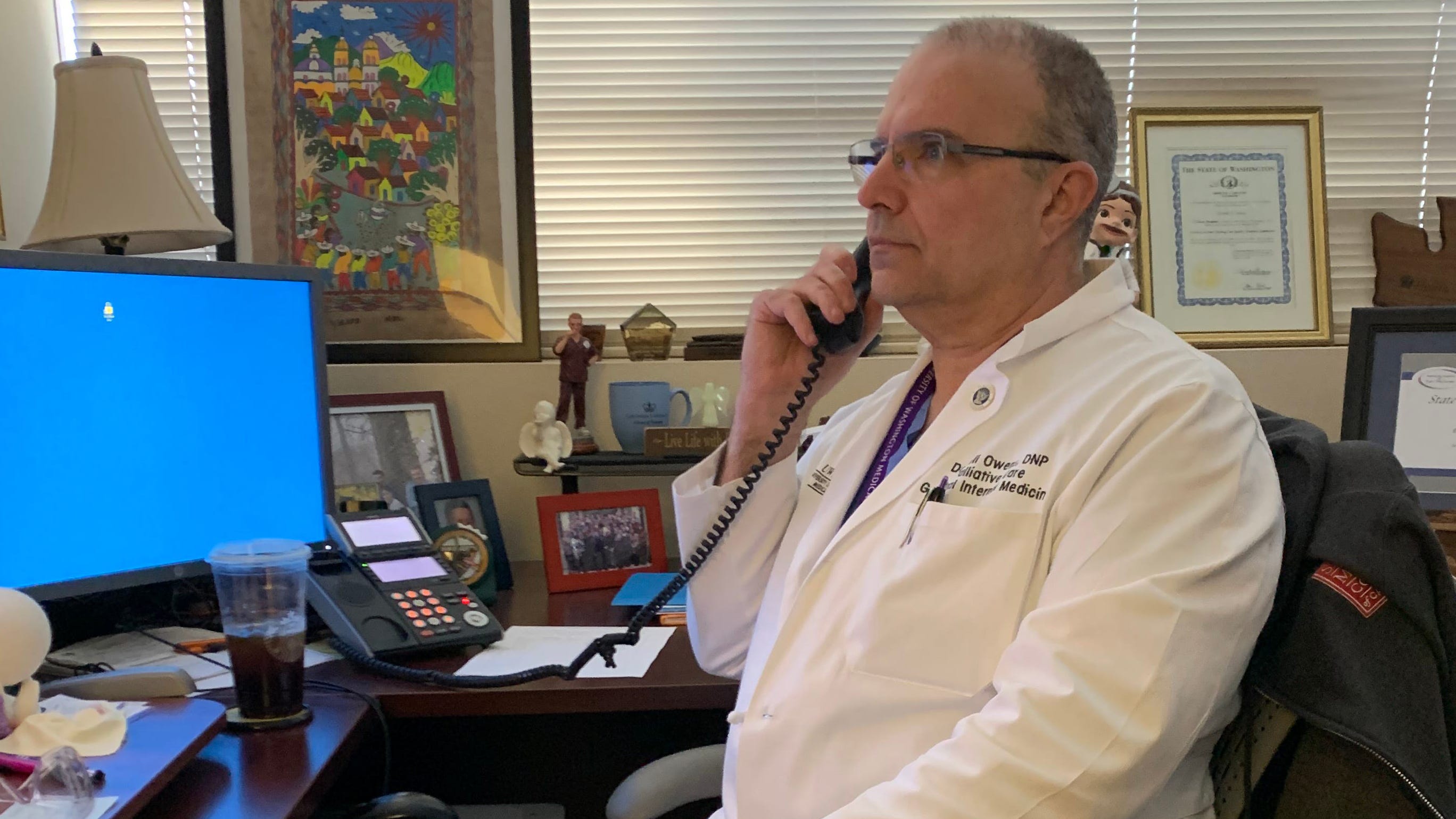

Darrell Owens checked in for his shift at the University of Washington Medical Center-Northwest in Seattle and braced for his first task of the day: Calling the family of a man in his 80s who had died overnight from the coronavirus.

The family hadn't seen the man in more than a month because he had been quarantined in a nursing home. He had checked into the emergency room the previous evening and died hours later.

As always, Owens, a nurse practitioner who heads the hospital's palliative care program, was careful to ask the relative where they were and who was with them.

He wants to make sure they aren't driving and they aren't alone.

"I say, ‘As we expected, so and so has died, so many minutes ago.' And then you just pause. You just let that painful silence be there.”

Recently, five patients died during one shift. The next day, three patients died, then two. In each case, Owens had to make the call to the family and signed each death certificate.

The Seattle region was the original epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. The first confirmed case of the virus in the country was reported in January, 50 miles north of Owens' hospital.

As of Saturday, King County, which includes Seattle, had reported 282 coronavirus deaths – or more than half of the state's 496 deaths.

For the most part, Owens, 56, tries not to think of the constant stream of death and despair rolling past him each day on gurneys. He has dinner with his husband and teenage son each night. He watches reruns of "Adam-12," a police procedural from the ‘60s.

There have been moments when he couldn’t hold it all in.

On one of his shifts, he watched an elderly couple succumb to the virus within 48 hours of each other. He called the family, then went home. On the TV that night, the local news aired a segment on the couple.

Owens burst into tears.

His son walked over, gave his father a hug and whispered: “I’m sorry you’re going through this, Dad.”

'I've never cried'

The hotline at the University of Washington School of Medicine has been ringing consistently with calls from doctors, nurses, social workers and others weighed down by the enormity of the outbreak.

Doctors call to confess while huddling in hospital corridors, trying to contain their emotions. Nurses call on their days off, expressing guilt about being away from the frontlines.

“I have people telling me, ‘I’m having to close my door and find time to cry, and I’ve never cried in my 25 years doing this,’” said Mollie Forrester, who runs the hotline.

Her department is analyzing research from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to learn how post-traumatic stress disorder affected troops in battle.

"We know there’s an impact one, two years down the road," she said. "The science shows PTSD will come.”

In Detroit, there were 343 deaths

In Southfield, Michigan, a Detroit suburb, the dead are familiar: Three pastors, a local talk show host, three members of a local ballroom dancing group, a church drummer.

Stephen Kemp, founder and president of Kemp Funeral Home & Cremation Services, knew them all. Now, they are statistics, victims of the coronavirus.

Kemp's own wife and chief financial officer of their funeral home, Jacquie Lewis-Kemp, fell sick and tested positive for COVID-19, Kemp said. She quarantined in their home for three weeks, got better and returned to work.

Their funeral home would typically process around 25 bodies a month. Since April 1, they've seen 49, most of them COVID-19 victims. Last week, Kemp ordered a refrigerated trailer as his 17,000-square-foot home was almost out of room.

As of Saturday, Detroit had tallied 348 coronavirus deaths, while the rest of Wayne County reported 304. Oakland County, which includes Southfield, counted 316. Together, the three account for 70% of Michigan's deaths.

"It's not just a death," Kemp said. "They all have names. They all have families. Most of the families, I know personally."

Kemp had a visitation planned for Thursday evening for an elderly woman who died from the virus. Early that morning, her husband died suddenly, too. The funeral for the wife was postponed, as family members mourned the husband.

Kemp said he had 13 bodies that still needed physicians' signatures to complete their death certificates. He hasn't been able to reach the doctors because they've been so busy with other COVID-19 patients, he said.

He's worried the coronavirus will soon work its way into rural communities.

"It's an equal-opportunity invader," he said, "and it's coming."

Leaning on faith

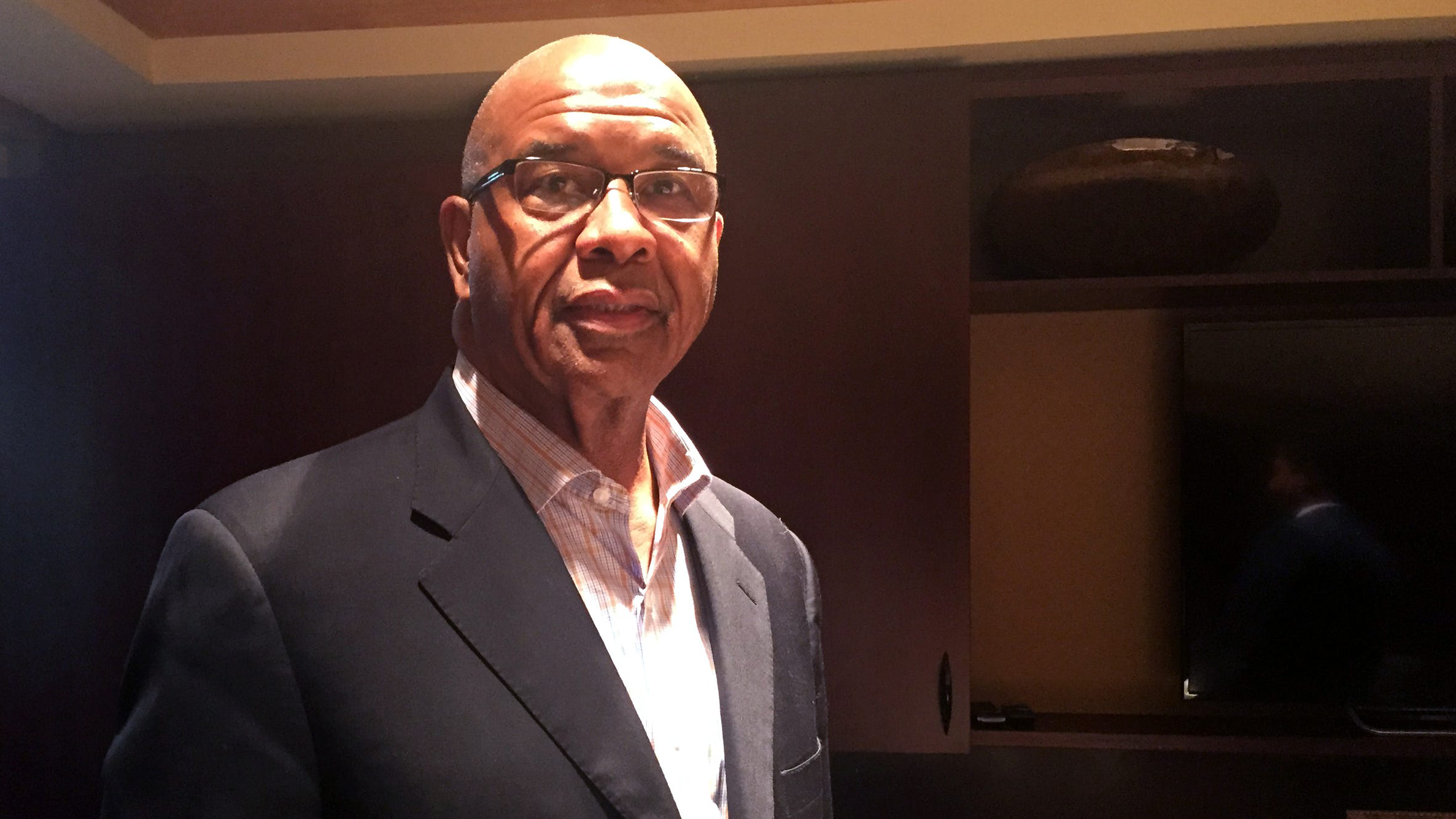

The Rev. James C. Perkins, pastor of the Greater Christ Baptist Church in Detroit, spends his days self-isolating at home, worrying and praying about the virus' assault on his church.

The coronavirus has killed three of the 800-member church's congregants and sent four to the hospital, including members of the men's ministry and the church's media team that recorded services. Two are on ventilators.

“We are a hugging, handshaking, high-fiving kind of a congregation,’’ Perkins said. “We won’t be able to do any of that for a while. It’s a different world.’’

The church can't hold funeral services, and funeral homes are restricting visitors to groups of 10.

Perkins, 69, can't join because of his age and the risk of contracting the virus.

"It’s extremely frustrating," he said. "You feel like you’re failing the family.''

Instead, he sends prayers to be read at the services.

Like the one for Robert Pontoo, a charter member who worked with the church credit union: "May you find your sorrows lightened and your faith strengthened by the thought that God is always near."

Perkins promises memorial services at the church once the virus retreats. For now, he's resigned to holding services virtually and calling congregants in need. And praying.

“This is a time like never before," he said, "when they have to really lean on their faith.”

A fire department confronts it humanity

Firefighters and paramedics at the Detroit Fire Department have been struggling under increased calls and loss of personnel. Of the 866 firefighters in the force, 52 have tested positive for COVID-19 and another 114 are quarantined, Deputy Fire Commissioner Dave Fornell said.

On Thursday, they got more bad news: Capt. Frank Williams, a gregarious and well-liked fire official from Engine 44, Ladder 18 on the city's west side, had died from complications from the coronavirus. He was the first from the force to die from the virus.

Williams' death is being classified as a "line of duty" death, which ordinarily would trigger an elaborate church memorial, firefighters from around the country and a 1937 pumper leading a long procession of fire trucks and white-gloved firefighters through the city, Fornell said.

With the coronavirus still rampant in Detroit, it's unclear if any of that will happen. "We're trying to figure that out now," he said.

In New Orleans area, there were 402 deaths

Each time the transport team from the Jefferson Parish Coroner's Office drives out to pick up a body, they go armed with gowns, gloves, N95 masks and extra body bags.

If the body is picked up at a house, they take an added precaution: A rag saturated in anti-virus solution is placed over the decedent's face, covering the mouth and nose, in case the cadaver lets out a postmortem exhale, a common occurrence, said Mark Bone, the coroner's chief investigator.

Jefferson Parish, adjacent to New Orleans, helped collect bodies, as the New Orleans area saw a surge of deaths attributed to the coronavirus. As of Saturday, Orleans Parish counted 232 deaths, while Jefferson Parish had 170, together comprising half of the state's 806 deaths.

The bodies bombarded area hospitals and overflowed morgues and funeral homes. Many ended up at the Jefferson Parish Coroner's Office in Harvey, six miles from New Orleans. When the bodies threatened to fill up that morgue, officials ordered a 50-foot refrigerated truck.

Since the outbreak began, workers at the Jefferson Parish Coroner's Office have handled more than 150 COVID-19 bodies.

"We are experiencing greater death loads per day than we did during Katrina," Bone said, referring to the 2005 hurricane that ravaged the Gulf Coast and killed around 1,300 in New Orleans.

On Tuesday, a transport team geared up and picked up a 39-year-old woman at her home in Harvey who had died of a drug overdose. When they arrived, neighbors informed them she had recently tested positive for COVID-19. They carefully placed the solution-soaked rag over her face, zipped her into a body bag and loaded her in the van.

'I was in a state of denial'

Corinne Barnwell is learning how to balance her bank accounts, decipher pension payments and maneuver through the Society Security Administration website. These are tasks her husband of 44 years, the Rev. William H. Barnwell, would have handled before the coronavirus took him away.

She had taken her husband, an Episcopal minster and civil rights advocate, to an urgent care clinic after he complained of back pain. The doctor diagnosed him with pneumonia, a symptom of the coronavirus, and ordered him to spend a night at Ochsner Medical Center, just to be safe.

William Barnwell, 81, had no chills or fever and expected to be released the next day. His condition, however, rapidly deteriorated. His lungs struggled and he was placed on a ventilator in an intensive care unit, where he fought to recover for 10 days. Corinne Barnwell, 83 and at risk if she caught the virus, wasn't allowed in.

She called each day, asking nurses or the hospital chaplain for updates. His condition plummeted.

"I was in a state of denial," she said. "I certainly didn't realize that we were going to be part of an epidemic right then and there."

When there was nothing doctors could do to revive William, his daughter from a previous marriage, Janet Barnwell Smith, donned a surgical gown, gloves and mask and entered her dad's room. She called Corinne via FaceTime and pointed her phone at her dad's bed. Corinne Barnwell watched from her living room as they removed her husband from the ventilator.

William Barnwell's body was cremated. The family plans to inter him in the garden behind Trinity Episcopal Church in the Lower Garden District in a few months, when family members can gather.

A few days after his death, a 100-car caravan drove slowly past Corinne's home, flashing their hazard lights and waving, a tribute to her husband's legacy in the city. Corinne waved back. The last car played "I'll Fly Away."

'You are not alone in your grieving'

Sister Alison McCrary's phone has rung steadily since the outbreak swept into New Orleans last month. A Catholic nun and spiritual counselor, she's fielded calls from distraught family members and friends trying to make sense of the scourge that snatches lives so abruptly and without reason or pattern. Overall, she’s taken more than 200 coronavirus-related calls since the start of the outbreak; seven of the victims she new personally.

But Thursday morning's call carried a particularly painful sting: Leona “Chine” Grandison, owner of the Candlelight Lounge in New Orleans’s Treme neighborhood, had died. McCrary, who is also a lawyer, had represented Grandison in her efforts to save the Candlelight as a live-music venue in Treme, an historic African American neighborhood and gathering place for musicians. Grandison and the Candlelight were their pillars.

"She was like a mom to a lot of us," McCrary said of Grandison, also known as "Ms. Chine." "Everyone knew and loved her."

In normal times, someone like Grandison would receive a jazz funeral and boisterous secondline – a spontaneous street parade with brass bands and dancers to celebrate a person’s life.

Instead, McCrary put on a surgical mask and created a homemade altar outside the Candlelight Lounge with Grandison’s framed photo, a bowl of meditation stones, pink hydrangeas, a rosary and a sign taped outside on the lounge’s wall: “Know that you are not alone in your grieving.”

'Is anyone among you sick?'

On Wednesday, Monsignor Christopher Nalty took the elevator to the sixth-floor intensive care unit at Touro Infirmary Hospital in New Orleans, pulled on a surgical gown, two pairs of gloves, booties, mask and a face shield and entered the room of an elderly African American woman he knew only as Gerry, who lay dying of COVID-19.

Using a dab of anointing oil on his gloved thumb, Nalty touched it to the woman’s forehead. The woman stirred but didn’t open her eyes. She was not on a ventilator but appeared sedated.

“Hello, Gerry,” he said.

Nalty, 57, is one of about a dozen hospital chaplains visiting dying coronavirus patients in New Orleans. They administer last rites or simply pray over them. Very often, the patients Nalty sees are alone with only a ventilator keeping them alive. He's often the last person with them before they die.

Before the outbreak, Nalty worked as a backup chaplain, seeing one or two patients a month, usually before a complicated surgery or after a serious prognosis. The patient would be conscious and surrounded by family. Nalty would joke, visit with family members, pray and calm nerves.

Now, he visits two to three patients a week, each ravaged by the virus and expected to die soon and alone. There are only masked nurses and doctors nearby. He's seen about 20 coronavirus patients so far.

Nalty doesn't fear being so close to the virus and is not afraid to die, he said. Still, he keeps a thermometer in his pants pocket and checks his temperature around 10 times a day, just to be safe.

For inner fortitude and solace, he visits the shrine of Francis Xavier Seelos, a German Catholic missionary who died in New Orleans in 1867 at the age 48 after ministering to victims of the yellow fever outbreak. Seelos is buried at St. Mary's Assumption Church in the Lower Garden District.

“Priests have always been there on the frontlines, in war and in times of plagues,” Nalty said. “We’re expected to be there at times of death.”

At Gerry’s bedside at Touro, Nalty said the Lord’s prayer and read from the Book of James: “Is anyone among you sick? Let them call the elders of the church to pray over them.” He asked God to pardon her sins.

“Gerry, we will be remembering you and all the sick here in our prayers,” he told the sleeping woman. He made the sign of the cross, peeled off his protective gear at the door and left the room.

Outside, a few nurses walked over and asked him to pray over them, as they often do. He obliged. Nalty said he’ll keep praying over patients and hospital staff for as long as the virus is around. His main motivator is seeing patients facing death alone, he said.

Recently, while at confession with an elderly priest, the priest asked Nalty how he’d like to be remembered when he’s gone.

He answered: “Just that I was there.”

Follow Jervis on Twitter: @MrRJervis; Gomez at @alangomez; Berry at @dberrygannett.