For months now, America’s business press has been telling us that the country is facing a historic labor “shortage,” thanks to the low, low unemployment rate. Bosses are scrounging to find workers and sweating over the possibility of having to hike pay as their employees threaten to quit for better jobs, we’ve been informed. The odd hysteria reached its zenith on Thursday, with a tweet from CNBC that might as well have compared the mere threat of rising wages to the plague:

Maybe that’s just what clickbait for the C-suite set looks like?

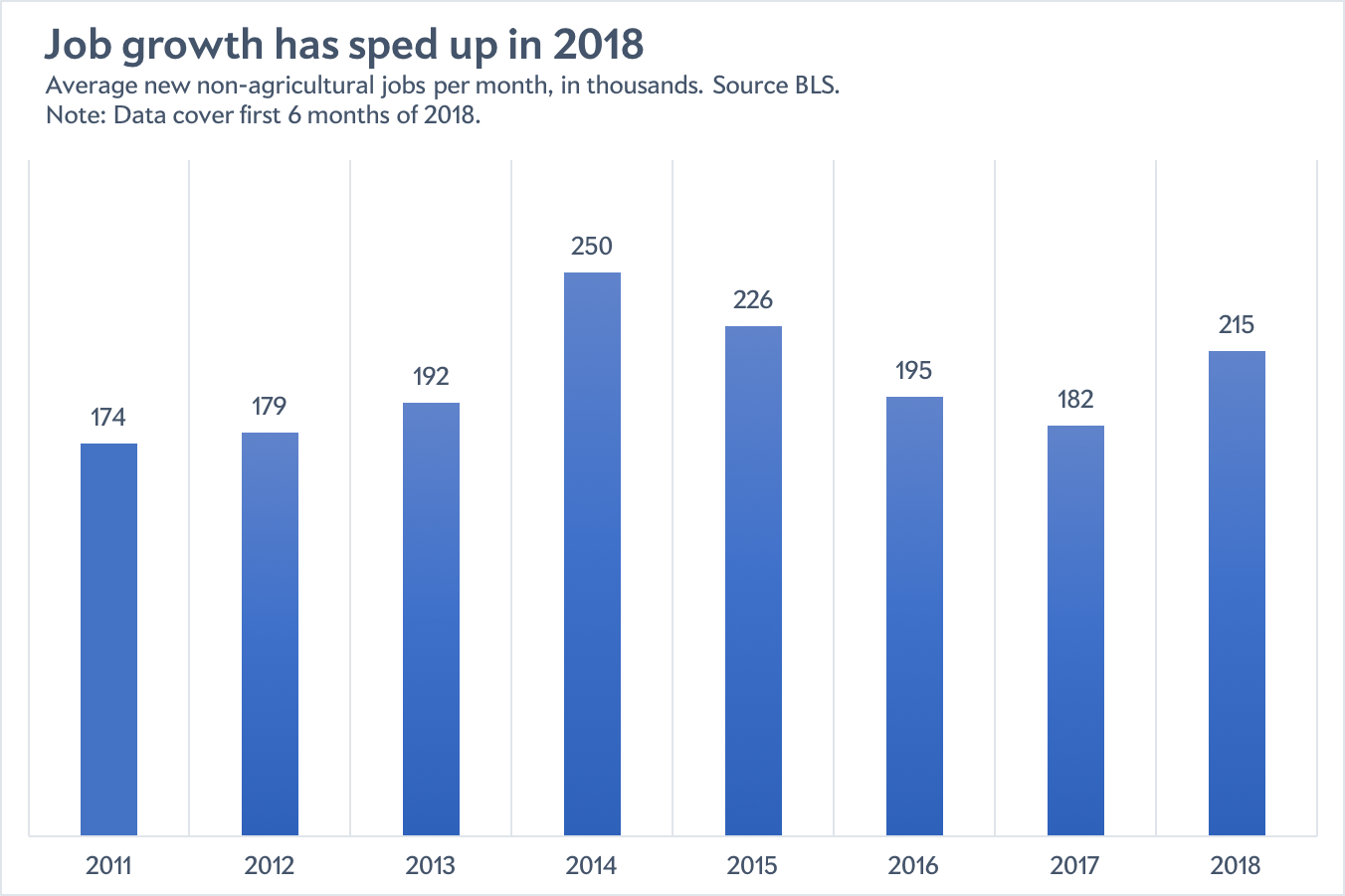

And yet: Despite all the hype about shortages, companies still seem still seem to be finding plenty of people to hire. The U.S. added 213,000 new jobs in June, the government reported on Friday, bringing the average for the first half of 2018 to 215,000 per month. Payrolls are actually growing faster this year than they did in 2017 or 2016.

This is not what you would expect to see in a country facing a crippling dearth of employable adults. If there literally weren’t enough workers to go around, job growth would eventually have to tail off. That, of course, isn’t happening. Despite the low official unemployment rate, employers are filling somewhere north of 200,000 new positions, month after month, far more than is necessary to keep up with population growth.

One reason for this dissonance is that when some people say there’s a “labor shortage,” they don’t literally mean there isn’t anybody around to hire. Rather, they mean that companies can’t find what they consider traditionally qualified applicants willing to work at the exact wage management wants to pay. One theme that’s come up again and again in articles this year is that companies are finding themselves hiring people they might not have a couple of years ago, such as ex-cons or teenagers. In its piece Thursday, CNBC suggested that businesses might have to start spending more money on training their staff, God forbid. But none of that means there’s a shortage of labor per se. It’s a sign that the economy is good enough that people who wouldn’t have been able to find work before now can. Only a Walmart executive or a McDonald’s franchisee could view that as crisis.

It’s possible, of course, that the U.S. could be adding jobs even faster if there were more workers to go around. There are signs, for instance, that employers are having a somewhat harder time filling job vacancies, which could be holding back the economy slightly. It’s also possible that individual cities or towns might really be hurting for workers, especially in parts of the Midwest where populations have been declining.

But along with the strong headline jobs number, Friday’s jobs report offered other evidence that there are still plenty of workers available for the hiring. For instance, the unemployment rate went up. That was because the government only counts people as officially “unemployed” if they are hunting for work while jobless, and last month more Americans dipped back into the labor pool to go looking for employment. In other words, people saw the economy was getting better and got off the sidelines. Meanwhile, hourly wages are still growing at well under 3 percent year-over-year—slower than before the Great Recession—suggesting that companies still aren’t facing intense pressure to hike pay. Overall, the numbers paint a picture of a steadily improving job market that’s been getting friendlier to workers, but still has yet to reach its full potential. It’s the same basic trend we’ve been looking at for years. We should only be so fortunate for it to suddenly turn into an “epidemic” of higher pay—but we’re not there yet.