Everyone has their own personal workout-to-race conversion. Take five runners who each complete an identical predictor workout at the same nominal effort, and they’ll produce five different times in their next race. And those conversion factors aren’t constant. When the stakes are highest, some runners find an extra gear, while others get stuck in neutral. Pressure does funny things to people.

I’ve been thinking about clutch performance—and its mirror image, choking—thanks to a recent study of baseball performance published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. Three researchers who all formerly worked with Los Angeles Angels analyzed the pitching, hitting, and fielding performance of 1,477 Major League Baseball players who competed in postseason games between 1994 and 2019. The results are pretty much the opposite of what I would have expected, which tells us something interesting about either clutch performance or, perhaps, about another hot topic in pro sports, load management.

The basic idea of the study is fairly straightforward. The researchers quantify pitching performance with a metric called Fielding Independent Pitching; batting with Weighted Runs Created Plus; and fielding with Errors per Inning Out. The details of these metrics aren’t important here, but they give simple measures of how well a player is performing.

Based on their regular-season stats, the players were divided into four tiers in each metric: excellent, above average, average, and below average. The researchers wanted to know if players in these tiers responded to playoff pressure differently.

On the whole, players got worse in the playoffs. This is not surprising, and similar findings crop up in other sports. For example, a 2015 study of more than 2 million free throw attempts found that basketball players were more likely to miss free throws in the final 30 seconds of tight games. WNBA players got 5.8 percent worse, NBA players got 3.1 percent worse, and NCAA women and men got 2.3 and 2.1 percent worse respectively. Again, not surprising—but there was a twist. College players who went on to play professionally had a six-percent bigger drop in accuracy than those who didn’t make the pros. The better players choked more than the worse ones.

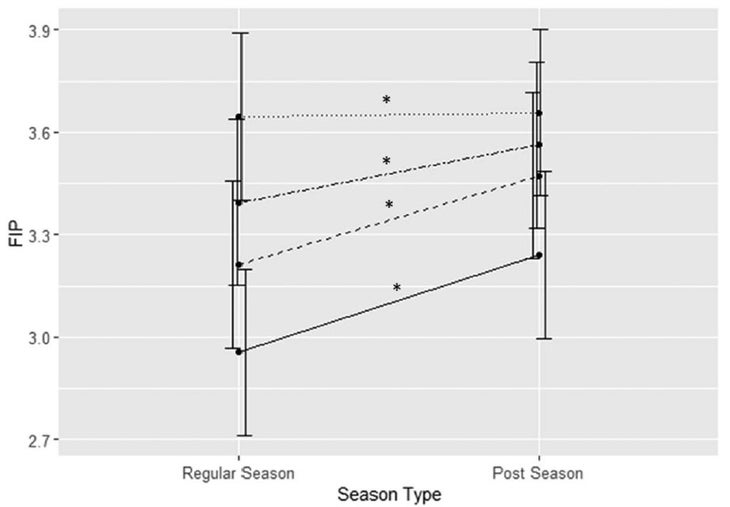

This pattern, it turns out, shows up in the baseball data too. Here’s the average pitching data for regular seasons versus playoffs, broken down by performance category. A lower number indicates better performance; the solid line is the excellent group, dashed line is above average, dot-dash is average, and dotted line is below average.

The sub-par pitchers stay at their usual level, but every other category gets worse in the playoffs, and the best pitchers see the biggest drop-off.

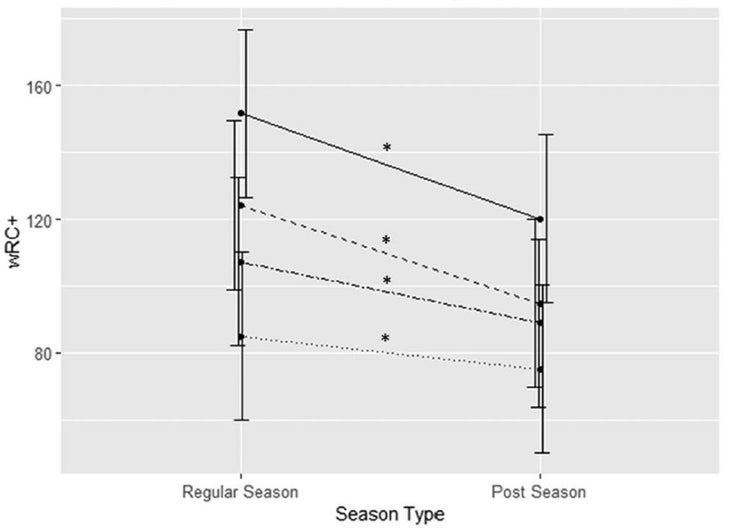

Exactly the same pattern appears in the batting data, with higher numbers indicating better hitting:

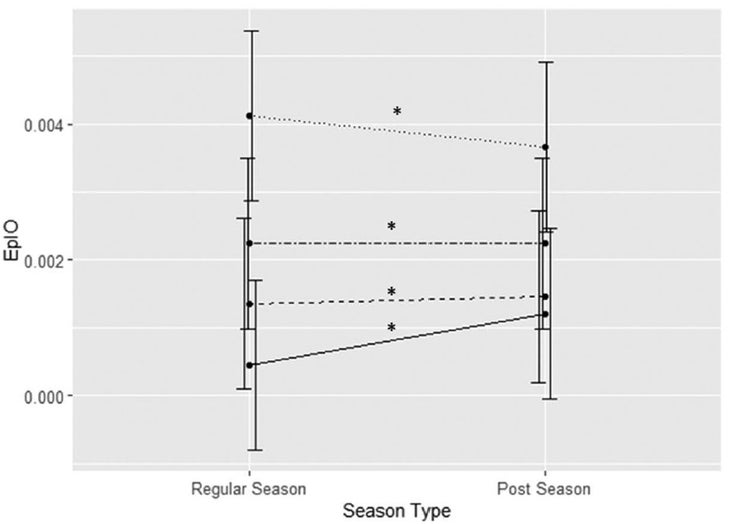

The fielding data is slightly different, in that the worst fielders actually manage to pull their socks up and do a little better in the postseason. But the overall trend between performance levels is the same, and only the excellent fielders get significantly worse. Lower numbers are better in this case.

The explanations that the authors consider fall into two broad categories. One is psychological: top players are more likely to choke in the pressure-cooker environment of the playoffs, perhaps because their teams are relying on them more heavily and their success or failure has greater consequences. The other is physiological: baseball has a very long season, with 162 games for each team, and top players get heavily used and are more likely to be tired or injured by the end of the year.

Both of these hypotheses are plausible, and we don’t have enough evidence to choose between them. But what I find most interesting is where the two hypotheses overlap. Do top players choke—that is, do their minds fail them—in part because they’re aware that their bodies are no longer in peak form? Or conversely, do attempts to allows stars to rest up during the regular season and save themselves for the playoffs—the much maligned “load management” philosophy that has gained prominence in the NBA in recent years—risk messing with their heads by ramping up the pressure they feel when the playoffs finally arrive?

These themes turn up in a great article on load management by Katie Heindl, published last week by Arizona State University’s Global Sport Institute. She quotes sports scientist Franco Impellizzeri, of the University of Technology Sydney, on the unintended psychological effects of holding athletes out of competition. Impellizzeri is skeptical that teams can use training data to reliably predict when an athlete is at higher risk of getting injured, and he worries that imposing extra rest on them can hurt their confidence. “There’s a risk in these kinds of decisions,” he says.

All of this makes me think back to my freshman year of college, when our underdog cross-country team unexpectedly qualified for the national championships. The week before nationals, we had a team time trial, which struck me as an odd decision after an already-long season. I had a mediocre performance and finished last in the time trial; a week later, I was our team’s second scorer. In fact, the team’s finishing order at nationals was almost perfectly reversed from the time trial. The only teammate who beat me was the one team member who had missed the time trial.

I’ve always thought of this as a story about mindset: I was able to elevate my performance when it mattered most. (Hold on a sec while I pat myself on the back.) But I probably haven’t given enough credit to a simpler explanation: those who pushed hardest in the time trial were more tired the following week. In fact, those two explanations are inevitably intertwined: seeing yourself as a “big-race runner” leads naturally to some load management, because you’re less likely to really go to the well in races you perceive as insignificant.

That’s a problem for Olympic selection policies in countries that (unlike the United States) emphasize repeated “performance on demand.” If every race is a big race, there are no big races. More generally, it illustrates the complicated relationship between physical and mental readiness. I don’t think we can draw any universal conclusions from the baseball data about whether star athletes are more likely to choke: those findings are specific to the demands of professional baseball. But perhaps we should be more careful about how we label people as chokers or clutch performers. If you’re an athlete who’s always firing on all cylinders, there’s nowhere to go but down.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.