Ingesting carbohydrates has long been known to improve endurance performance, primarily during events lasting longer than 45 minutes. But there has been a backlash against carbohydrate fuelling in recent years, alongside the emergence and growth in popularity of the concept of using fat as the primary fuel for endurance.

This debate has driven a wedge between those who are resolutely ‘pro carb’ and those who fervently practice Low Carb, High Fat diets (LCHF). This blog looks at why the topic is so polarising and what the current evidence suggests is best practice for endurance athletes.

Early research into carbohydrate fuelling

Check out this abstract for a paper examining the potential benefits of carbohydrate ingestion for athletes in 1925...

The chemical examination of the blood of a group of runners who participated in the Boston Marathon showed that the sugar content at the finish of the race was moderately diminished in two runners and markedly diminished in four. There was, furthermore, a close correlation between the physical condition of the runner at the finish of the race and the level of the blood sugar.

In making the report, it was suggested that the adequate ingestion of carbohydrate before and during any prolonged and vigorous muscular effort might be of considerable benefit in preventing hypoglycemia and the accompanying development of symptoms of exhaustion.

It’s widely acknowledged that this paper is the earliest formal study of the use of carbohydrate supplementation to improve endurance performance.

It goes on to describe how runners who carb-loaded the day before the next Boston Marathon and then consumed sugar (in the form of sweet tea and confectionery) during the marathon almost all ran faster, had improved post-race blood sugar levels and were in better general condition than they had the prior year.

Therefore, it’s the earliest scientific evidence that eating carbs is a good thing if you’re doing a long, hard endurance event.

I think it’s fair to say that, at a simplistic level at least, the researchers’ conclusion that consuming additional carbs the day before a hard endurance event, and then some easily digestible carbs during it, is the best way to maintain performance and reduce fatigue, holds true nearly a century later.

How your body uses carbs and fat to fuel exercise

The reason the researchers in Boston chose to give the runners candy and sweet tea during the event rather than bacon or butter was that, even back in the 1920s, we understood that carbohydrate is the body's preferred source of energy during higher intensity exercise and that running out of carbs is a sure-fire way to induce premature fatigue.

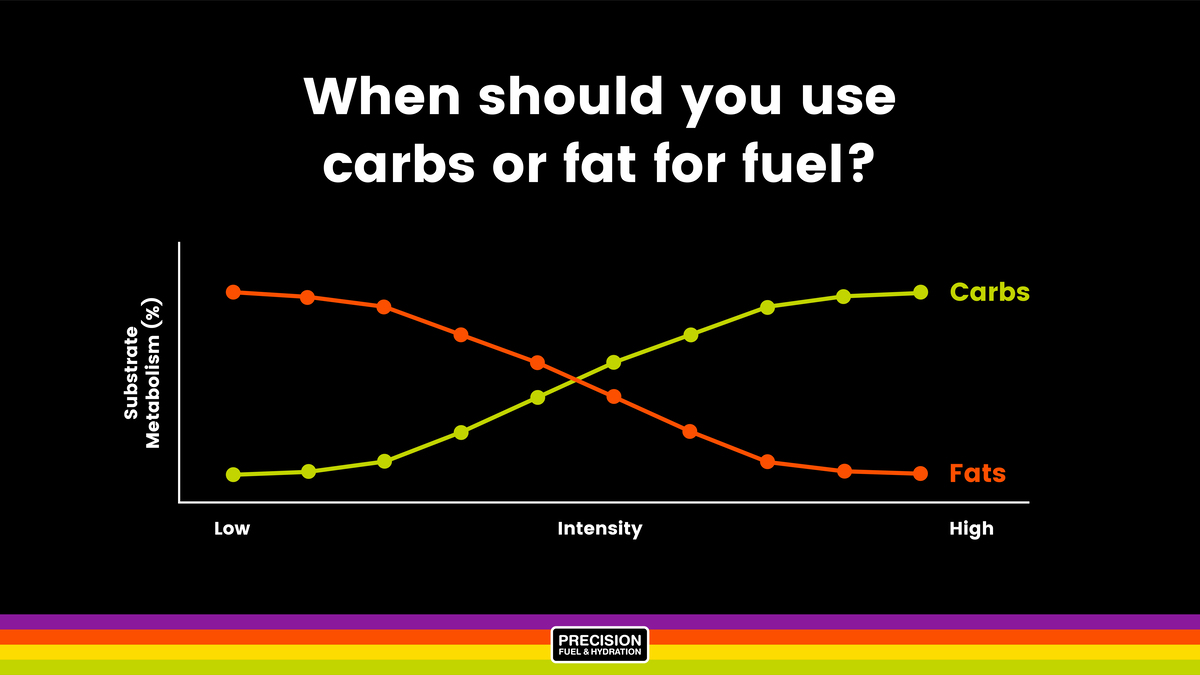

A simplified but illustrative way to think about how fuelling for exercise works is on a continuum, with fat as the primary source on the extreme left and carbohydrate on the right. This is known as the crossover concept and was first described in the 1990s.

The left side of the graph aligns with very low intensity activity (e.g. zone 1-2 training, walking, jogging or spinning on the bike) and the right represents really hard, high intensity activity (e.g. repeated sprinting or going at a relatively high percentage of VO₂ max for sustained periods of time).

Fat is preferentially used for low intensity exercise because it requires a lot of oxygen to break it down into fuel for your working muscles (and oxygen is more abundant when you’re not working too hard!).

It’s also extremely energy-dense and, because we have lots of it stored in our bodies, it will basically never run out in a sporting context. Even quite lean people have ~100,000 calories available as stored fat!

At the opposite end of the spectrum, carbohydrates are needed when exercising hard because their energy can be released far more quickly and easily than from fat - and without as much oxygen - which is clearly less abundant when you’re ‘red-lining’.

But, there’s a big trade-off here. Even when recently fed, the average person has only got about 2,000 calories of carbohydrate stored in their body (as glycogen) and you can burn through pretty much all of that in 90-120 minutes of hard exercise.

So carbs represent ‘fast’ fuel for working hard, but are in somewhat limited supply and need to be topped up frequently if exercise intensity is to be sustained beyond the point when your glycogen stores start to become depleted.

Crudely speaking, the mixture of fat and carbohydrate used to power your activity changes to reflect your relative intensity. At lower intensities, you’ll use proportionally more fat. You’ll burn more carbs as your effort level increases.

This all gets interesting when you begin to look at what point along the continuum you generally start burning significantly more carbs than fats (i.e. the crossover point); and when you ask whether anything can be done to shift the point at which your fat-burning ability drops off.

Can fat be used as a fuel for endurance exercise?

Fatigue in endurance exercise is a complex topic and Alex Hutchinson’s brilliant book ‘Endure’ dives deeper into the topic than I can in this blog. But one thing that has been known for decades is that running out of glycogen - commonly called a ‘bonk’, ‘the knock’ or a ‘hunger flat’ by cyclists and ‘hitting the wall’ by marathon runners - is a recipe for a pretty immediate and catastrophic deterioration in performance.

It’s the physiological equivalent of running out of petrol in your car. If you’ve ever experienced it, you’ll know exactly what I mean. Even the best in the world have suffered, and pro tour cyclist Nico Roche shared his experiences of 'bonking' with us...

So, it’s long been something of a Holy Grail for athletes to find a way to tap into the body’s fat stores and use them preferentially to carbohydrates, preventing or putting off the bonk for longer.

An infamous 1983 paper explored this in detail, seeking to take advantage of the adaptive nature of human physiology to ‘learn’ to burn more fat through dietary manipulation.

The study compared the performance of cyclists in a time trial to exhaustion after they’d either followed several weeks of a ‘normal’ diet containing around 60% carbs, or a very low carb (ketogenic) diet containing less than 20g of carb per day (less than in one banana) and a lot more fat to make up the difference in calories.

Interestingly, the study showed basically no difference in the time to exhaustion in the time trial, suggesting that fat can indeed power a similar level of steady-state endurance performance as sugar.

The physiological measurements taken demonstrated that the cyclist’s bodies had significantly adapted, learning to burn more fat, more effectively in the weeks on the ketogenic diet. This had protected their muscle glycogen stores far more than was the case when carbohydrates made up a larger proportion of the diet. In essence they had indeed shifted the fat-burning point to the right of our ‘exercise intensity continuum’.

It’s worth noting that, although the main part of the study looked at submaximal steady-state endurance performance, the riders’ performance in anaerobic (i.e. sprinting) tests was significantly blunted on the ketogenic diet, as the fat-adapted cyclists struggled to burn energy quickly enough to produce really high power outputs for short periods.

There was also the fact that, whilst on average performance was maintained in the group, some participants fared much better than others with the different dietary approaches. This is a very important point and I’ll come back to it a bit later on.

The rise of low carb diets

Phinney’s 1983 paper aside, during the latter part of the 20th century, sports nutrition research was dominated by investigations into the impact of taking in carbohydrates. And the general consensus was that carbs were ‘rocket fuel’ for endurance and their intake should be prioritised by athletes.

It was only after the turn of the millennium that a groundswell of anecdote from maverick ultra endurance athletes, who claimed to be training themselves to be ‘fat-adapted’, started to pique the interest of sports scientists and nutritionists.

One reason why going low carb for athletic performance started to go more mainstream was that eminent (and controversial) sport scientist Dr Tim Noakes (whom we’ve written about before in relation to hydration) fully endorsed the idea of ketogenic diets for athletes. This was a dramatic U-turn given that he’d spent the majority of his career so far promoting carbohydrate use instead!

Noakes’ influence led to many more people experimenting with the approach in an attempt to improve their performance. This led to further research into fat adaptation. Arguably the most interesting and influential of the more recent studies into low carb diets and endurance performance have been conducted by Louise Burke and her colleagues at the Australian Institute of Sport.

Between 2015 and 2020, they ran two variants of a large study on elite race walkers, where LCHF diets were tested against more traditional forms of high-carb fuelling, to see how they affected metabolism and performance in actual race-like situations.

Alex Hutchinson has written extensively on these studies, pointing out that, although they both demonstrated impressive enhancements in athletes’ ability to burn fat and spare glycogen stores, none of this translated into any real world performance gains whatsoever. Which is, ultimately, what actually counts when dealing with competitive athletes.

Also, the changes in metabolism that eating a LCHF diet triggered came at the expense of efficiency and blunted top-end speed and power (as also reported in Phinney’s 1983 paper), something that represents a significant competitive disadvantage in most sports where relatively brief periods of high intensity effort (like climbs or head-to-head sprints) contribute significantly to the outcome.

Carbs vs Fat - what do elite endurance athletes use?

The evidence provided by Burke’s studies goes a long way to validating the kind of high-carb approach to fuelling that we see practiced by the overwhelming majority of elite endurance athletes in the real world today.

Through our own work with professional athletes and teams in a whole host of endurance events, from IRONMAN triathlon to ultra marathon runners and Pro Tour cyclists, we’re lucky enough to get pretty detailed insights into what elite guys and girls eat and drink to support their intensive training regimes and arduous races.

Despite the huge amount of chatter online about the benefits of LCHF diets for performance, it’s genuinely not an exaggeration to say that we’re yet to come across anyone consistently practicing a truly low carbohydrate strategy at the elite level in endurance sports, especially during phases of hard training or races.

These folks hit the carbs very, very hard indeed. This is an important observation because usually if there’s some advantage, however slight, to taking a different approach to your competitors, in elite sport a way will be found of exploiting it!

Whilst many elite athletes have tested LCHF approaches, it has not gained a significant amount of traction at the top end of sport. Sport at the highest level is a brutally competitive, evolutionary process that selects for concepts that work and deselects those that don’t pretty quickly.

I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that LCHF diets have so far failed to pass the acid test of being widely adopted by elite athletes who habitually tend to double down on things that maximise their chances of winning.

Respected physiologist Trent Stellingwerff has made similar observations from his extensive work with elite athletes. In 2015 he published a paper detailing the Competition Nutrition Practices of Elite Ultra Runners where he highlighted that, although many in the sport of ultra running claimed anecdotally to be following variations of a LCHF approach, when their race nutrition intake was properly studied, it actually contained very high levels of carbs. The athletes’ carb intake levels were in line with current sports nutrition guidelines, at around 70g per hour and showed very low levels of fat.

He has also been quoted on numerous occasions as saying that for ‘Olympic-level endurance athletes’, a low-carb approach to competition is not warranted due to the very high levels of intensity demanded in the kind of sports represented at the Olympic Games.

Lisa Nijbroek - the head nutritionist for Team DSM on the UCI World Tour - shared similar sentiments from her work with some of the very best cyclists in the world...

Training low leads to training adaptations at a muscular level, which means that your fat metabolism will be stimulated and your glycogen amounts will be saved until a later moment in the race.

Theoretically, this sounds interesting for (extreme) endurance sports, since glycogen will be predominantly used during intense efforts.

However, for almost all of the "train low" methods, there's been no performance benefits exhibited.

So you could ask yourself: why train low if you're not sure about racing faster? Is it worth the potential negative side-effects of disturbed sleep, less quality of training, extended recovery time required, and potentially underfuelling?

If you perform low carb efforts, my advice would be to make sure that it's undertaken during sessions that aren't dedicated to heavy training loads.

Some pre-ingestion of caffeine might help you perform your low carb training more effectively.

Low carbohydrate training should always be undertaken alongside high carbohydrate training sessions during the same week, where the intended competition fuelling schedule is simulated (e.g. up to 90 g of carbohydrates per hour for long endurance sports).

So, does this mean carbs are a better endurance fuel than fat?

The available evidence suggests that, as was the hunch of the Boston Marathon researchers in 1925, fuelling hard endurance efforts with adequate carbohydrate is still the best nutritional approach to maximising endurance performance that we currently have at our disposal.

With that being said, some selective and intelligent use of periods of low carbohydrate availability may be useful in training to drive enhanced adaptations and to make the most of fat burning abilities where they could offer an advantage...

When a LCHF approach makes sense

Whilst I do firmly believe that fuelling with plenty of carbohydrate is critical to support high levels of performance and recovery around hard training and most endurance races, this is not the same as saying athletes should universally eat lots of carbohydrates AT ALL TIMES.

It’s fair to say that there is likely to be a very large degree of individual variation in how people respond to different diets, with some doing exceptionally well (and others really badly) on LCHF for reasons that are not yet fully understood.

This was partly demonstrated in the 1983 study where performance on the keto diet was markedly different for some individuals in the group and mirrors what we see in many areas of the study of training and physiology; that there are ‘responders’ and ‘non-responders’ to most physiological stimuli.

Here’s when a low-carb diet might be beneficial:

1. If you’re in a phase of training where weight loss is a key target

Whilst the studies and wealth of anecdotal evidence from athletes practicing LCHF approaches haven’t shown evidence of outright performance enhancement over a high carb diet, they have demonstrated comprehensively that by shifting intake away from carbohydrate and towards fat for prolonged periods of time, you can genuinely teach the body to burn more fat, more effectively.

And, on a simple level, this may be very useful for weight loss, which can of course be performance-enhancing in some cases. However, there’s a big caveat here in that weight loss is definitely not always useful or indeed healthy for athletes. Any serious change in body composition needs to be done in a suitably controlled way if it’s deemed necessary. Please see this blog on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) for more information on why that needs to be approached with caution.

Some implementation of a LCHF approach may also help the body to learn to preserve glycogen stores during submaximal exercise and promote a level of ‘metabolic flexibility’ - that is making it less highly reliant on carbs than it would be if they are prevalent in the diet 100% of the time - something that has wide ranging health benefits, as well as potential performance benefits.

2. When you’re exercising for very long durations at a low intensity

For those who do respond especially well to a LCHF approach, it’s definitely plausible that being fat adapted could offer significant advantages when it comes to fuelling very, very long, even-paced endurance events at a low-to-moderate intensity, where fat is a more ideal fuel source than carbohydrate.

This is probably for events lasting ~12+ hours and where the need to change pace is limited. 100 mile track running world record holder Zach Bitter (who ran a mind blowing 6 minutes 48 seconds per mile for the century distance in 2019) appears to be such an individual, though even he admits to using carbohydrates as ‘rocket fuel’ to see him through selected workouts and higher intensity efforts.

A highly selective (rather than complete) low-carb approach to fuelling centred around certain specific workouts or phases of training being undertaken in a low carb state could also be very useful for stimulating greater overall adaptations in muscles to endurance training and enhance subsequent fuel utilisation abilities.

This topic is addressed in great detail on this podcast with Sam Impey, a leading researcher into a topic he has called ‘Fuelling for the work required’ and does feel like it represents a really practical use of LCHF practices as it’s being adopted by many successful elite athletes already.

Looking ahead, we can definitely hope for more research and field-based evidence to emerge in this specific area in the coming years, as this avenue of performance nutrition attracts more and more interest. But I will stick my neck out and offer the prediction that race-winning marathon runners in 2125 will still be ingesting carbohydrates on their way to victory - assuming they’re not genetically modified by then!