The Strangely Revealing Debate Over Viking Couture

An archeological discovery has raised questions about Muslims’ influence on Europe.

A researcher at a Swedish university says that Viking burial clothes bear the word “Allah”—and some people really want to believe her.

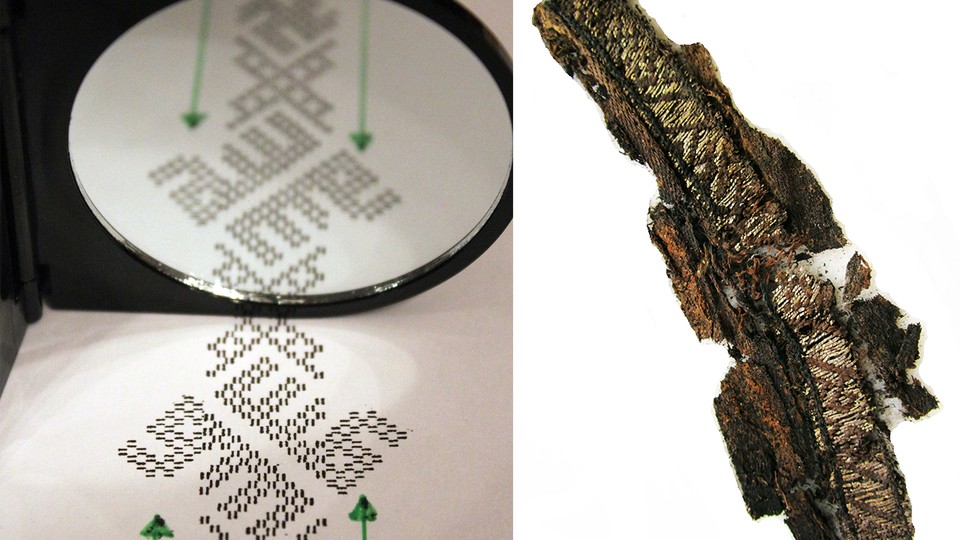

Annika Larsson, a textile researcher at Uppsala University who was putting together an exhibit on Viking couture, decided to examine the contents of a Viking woman’s boat grave that had been excavated decades ago in Gamla Uppsala, Sweden. Inspecting the woman’s silk burial clothes, Larsson noticed small geometric designs. She compared them to similar designs on a silk band found in a 10th-century Viking grave, this one in Birka, Sweden. It was then that she came to the conclusion that the designs were actually Arabic characters—and that they spelled out the name of God in mirror-image. In a press release, she described the find as “staggering,” and major media outlets (including The New York Times, The Guardian, and the BBC) reported the story last week.

But other experts are not sure the silk bears Arabic script at all, never mind the word “Allah.” They warn that people being credulous of Larsson’s claim may be guided less by solid evidence than by a political motivation: the desire to stick it to white supremacists.

“Everybody wants a counter-narrative for the narrative that’s been put forward by white supremacists,” said Stephennie Mulder, an associate professor of Islamic art and architecture at the University of Texas at Austin. She was referring to the tendency of white supremacists to appropriate the symbols of Vikings, whom they claim constituted a pure-bred white race; in Charlottesville, for example, neo-Nazis were seen toting banners with Viking runes. The idea that Vikings were influenced by Muslims would likely be anathema to them. “The Vikings are every white supremacist’s favorite white guy.”

Mulder took to Twitter on Monday to debunk Larsson’s claim. In a 60-tweet thread, she described her three main issues with it.

First, the style of Arabic that Larsson says she has identified—square Kufic—is not known to have been used in the 10th century; it only became common about 500 years later.

It’s a style called square Kufic, and it’s common in Iran, C. Asia on architecture after 15th c., ex: Safavid Isfahan w/Allah and Ali 9/60 pic.twitter.com/pbGJNFITGk

— Stephennie Mulder (@stephenniem) October 16, 2017

Second, even if you read the script as Arabic, it does not say “Allah” but “lllah,” a meaningless non-word. In place of an alif or “a,” it has a lam or “l.”

The word “Allah” in Arabic looks like this: الله. It has an upright alif, two more uprights (lam), and a final ـه 'ha' 29/60

— Stephennie Mulder (@stephenniem) October 16, 2017

Third, the end of the word “Allah” does not actually appear in the artifact; instead, it’s part of what Larsson imagines might have existed beyond the edges of the frayed fragment we have today. Larsson is looking at the pattern that’s visible and extrapolating what may have been beyond it, as part of her attempt to reconstruct what the artifact might have looked like in full.

There is a small triangular shape, but no final ha ـه. Frag. was published in 1938 by Agnes Geijer, original drawing looked like this: 31/60 pic.twitter.com/DxDossuWzs

— Stephennie Mulder (@stephenniem) October 16, 2017

But reconstruction drawing by @UU_University textile archaeologist Annika Larsson shows extensions on either side that include a ha. 32/60 pic.twitter.com/1NyQzcqDV2

— Stephennie Mulder (@stephenniem) October 16, 2017

These extensions practically double width of band. Not mentioned in press accounts: Larsson’s extensions are entirely conjectural. 33/60

— Stephennie Mulder (@stephenniem) October 16, 2017

This reconstruction is unfounded, according to textile expert Carolyn Priest-Dorman, who told me the artifact could not have extended farther out (to include the end of the word “Allah”) given how narrow its borders are: “Larsson’s saying the artifact was wider than it is.”

“She might be indulging in some fanciful readings that aren’t justified by the evidence,” agreed Paul Cobb, a professor of Islamic history at the University of Pennsylvania. He clarified that it’s already an established fact that the Viking world and Muslim world were closely integrated through trade and travel; he and other experts like Mulder and Priest-Dorman aren’t disputing that. They’re only disputing whether these specific burial clothes truly bear Arabic script.

“People want to see Arabic there, because it resonates today with a dream of a more inclusive Europe. There’s a real desire to document that Vikings had interactions, not to mention intermarriages, with many non-Vikings,” Cobb said. “That flies in the face of the white supremacists, who see Vikings as Nordic warriors defending Europe from foreign pollution, when nothing could be further from the truth. They were one of the great international societies of the Middle Ages.”

In fact, for Vikings, Arabic may have come with cultural cachet. They circulated coins bearing Arabic inscriptions, as well as weights for measuring silver bearing pseudo-Arabic inscriptions (writing that imitates the look of Arabic but doesn’t get it quite right). In a journal article for Current Swedish Archeology, scholar Lotta Fernstal writes that Vikings may have used the language to “‘spike’ certain objects with additional meaning” as part of constructing their self-image. “It seems likely that the Eastern, Oriental, Arabic and/or Islamic was alluring and desirable, perhaps as an ideal image of the ‘Other’ as part of a Viking Age Orientalism,” she adds.

Given this exoticizing attitude, Mulder said, it wouldn’t be surprising if Vikings were to have bought funeral clothes with Arabic inscriptions. “It would be like, for us, buying a perfume that says ‘Paris’ on it,” she told me. “Baghdad was the Paris of the 10th century. It was glamorous and exciting. For a Viking, this is what Arabic must have signaled: cosmopolitanism.”

Priest-Dorman added that it wouldn’t be unusual to find an eclectic mix of styles in the burial finery of a single Viking woman. “Everything beautiful goes with everything else beautiful—that is the Viking aesthetic.”

Still, the critics believe there isn’t yet enough evidence to support Larsson’s claim, and are concerned by how quickly her non-peer-reviewed findings went viral. “If stories like this are not fully fact-checked, white supremacists can then say, ‘Look, that wasn’t Arabic at all, the journalists are just pushing their PC agenda,’” Mulder said. Or as Cobb put it: “The story might well support my political views about Europe, but if it’s poorly documented, that makes it an easy target.”

In an email, Larsson indicated to me that additional details of her research are forthcoming. Another word that she says she discovered in the burial clothes—“Ali,” the name of the fourth caliph of Islam, revered especially by Shia Muslims—does not appear in the same artifact that purportedly bears the name of God. “Ali is not depicted in this ribbon. It is to be found on other ribbons that I’m working with and that is to be published in a coming work.”

Responding to critics who say that the burial clothes say “lllah” and not “Allah,” Larsson wrote, “If it is another word, it is still Kufic … that’s interesting.” She does not agree with the experts who say that there’s a dating issue with that claim and that “lllah” is a senseless jumble of letters.

“The meaning of research is to open questions,” Larsson added. “This discovery opens new questions.”

That, at least, is certainly true. Perhaps unusually for questions in medieval archeology, these questions feed directly into a contemporary heated political debate. The answers and debunkings of those answers are sure to be used as fodder by the left and the right alike.