For a few months before the pandemic trapped us in our homes, I spent a fair amount of time driving around the Midwest. Scouting out new developments in the realm of food and drinks is central to what I do here at Esquire, and I was excited to see that there were plenty of new developments to check out in states like Indiana and Ohio and Missouri.

I took a tour of Ryan Morgan’s bakery, Sixteen Bricks, in Cincinnati, and I slid into a booth at Martha Hoover’s candlelit chapel of cocktails and vintage albums, Bar One Fourteen, in Indianapolis. I knew that I would be a dolt to visit Cleveland without dropping into Larder, a deli and bakery that has become recently famous for its pickles and pastrami. I drove straight there from Columbus and parked a block away at lunchtime. St. Louis impressed me most of all. Within 24 hours I had three meals in St. Louis that rivaled anything I could find in New York or Los Angeles: lunch at Winslow’s Table, dinner at Indo, and a solo brunch (I was the first person in line when the doors opened at 11 a.m.) at Balkan Treat Box, which serves Eastern European flatbreads good enough to make you stray from pizza.

As I binged my way through these states, it was not lost on me that all three of them—Indiana, Ohio, and Missouri—had gone for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. Indiana and Missouri are core red states. Ohio (which pledged its electoral votes to Barack Obama in 2012) is a swing state so swingy that political observers have watched it for decades as if it were a weathervane. But I remember thinking that these Midwestern clusters of new bars and bakeries and restaurants—vigorously independent businesses, deeply personal businesses, places that tell us stories about culture and immigration and resiliency and nature—might represent a rising counterpoint, a kind of insurgency of delight, in regions of the United States that are still dominated by a monoculture of corporate chains.

Treat yourself to 85+ years of history-making journalism

Subscribe to Esquire Magazine

These are bars and bakeries and restaurants that have, for lack of a better word, a funk to them. That regional funk is the secret ingredient that makes all that bread at Sixteen Bricks and Larder and Balkan Treat Box so delicious. I couldn’t help but think that the food clusters in these cities echoed, in spirit, the regional music clusters that flooded college radio stations with new voices and ideas during the Reagan/Bush years of the 1980s and early 1990s. Minneapolis. Seattle. The South Bronx. Athens, Georgia. Dayton, Ohio. For a Gen Xer like me, acts like R.E.M., the Breeders, Hüsker Dü, and Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five didn’t just generate excellent music; they amplified and distributed ways of thinking that ran counter to the prevailing orthodoxy of political and economic power.

I believe that fiercely independent restaurants do something similar, particularly in parts of the country where they act as an antidote to everything generic, mass-produced, and shorn of funk. By their very presence, restaurants such as Winslow’s Table in St. Louis and Bluebeard in Indianapolis and Bouquet in Covington, Kentucky—right over the bridge from Cincinnati—tell us about the importance of supporting local farms, protecting the environment, and consuming more fruits and vegetables and sustainably raised meat and fish instead of the usual drive-thru burgers and factory-farmed dreck. These restaurants offer the green-state-ish idea that there’s a different way to use the land, and they serve as a reminder that there is an infinitude of American stories to be told about community and fellowship.

But these are the restaurants that are most at risk of vanishing altogether as casualties of the coronavirus shutdown, and it probably shouldn’t surprise anyone that the Trump administration so far doesn’t seem to care. (If regional food scenes, like regional music scenes, hint that alternative ways of thinking have gotten a foothold somewhere, why would an anti-environment, pro-pollution, anti-pluralism, pro-monoculture White House see any advantage in incentivizing that?) This week the James Beard Foundation and the Independent Restaurant Coalition released the results of a survey. The survey said that a vast majority of owners of independent restaurants—almost 80 percent of them—don’t think the CARES Act and the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) stand a chance of saving them.

We’re talking about 500,000 or so restaurants that employ 11 million people, according to the foundation. Not coming back, or viewing a comeback as a long shot. Think about that.

Meanwhile chefs from around the country—indie chefs fighting for the idea that their creations deserve to stay alive—expressed outrage that Ruth’s Chris Steak House, a corporate chain, had secured $20 million in government aid.

“This is absolute crap thanks for screwing the small business owner,” chef Chris Cosentino said on Instagram.

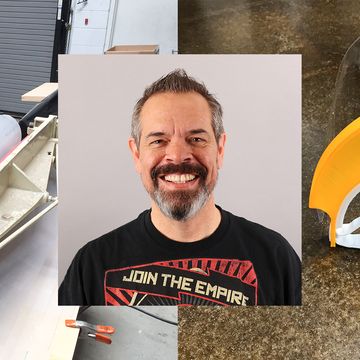

Indianapolis empire builder Martha Hoover posted a picture of an aristocrat (played by Roger Moore) smoking a cigar and chilling champagne in a bucket. "Thank you to my restaurant colleagues for sharing your outrage,” she wrote. “Ruth's Chris is sitting on 86 million dollars in the bank, yet they had the gall to request and now have received $20 million of the PPP fund—a fund intended to help small businesses. Since when do publicly traded companies count as small business? And, how many truly small, truly independent restaurants got blocked from receiving any of the SBA bailout? ... I hate using my social media space contributing to negative anything right now, but I am motivated to take my outrage and turn it into a pitchfork for change."

And San Francisco chef Mourad Lahlou posted this: “The real gems that make our neighborhoods so unique and special will all get fucked one way or another, sooner or later, if nothing changes RIGHT NOW … most neighborhoods will have the same shitty chain restaurants.” He added: “oh wait… that sounds like Trumpville.”

It’s an intriguing point. This same week the White House put out a list of people handpicked to rescue American restaurants from the brink of doom. The list included executives from Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Kraft, McDonald’s, Subway, Chick-fil-A, Papa John’s, Jimmy John’s, and Wendy’s, and then it cleared a little extra space for four old white guys from the world of white tablecloths: Thomas Keller, Daniel Boulud, Wolfgang Puck, and Jean-Georges Vongerichten, who recently (without irony) compared himself to Christopher Columbus. (That’s right: no David Chang, no Missy Robbins, no Martha Hoover, no Renee Erickson, no Kwame Onwuachi, no Edward Lee, no Michael Solomonov, no Nancy Silverton…) The implication is obvious, and it spells out Republican ideology with an uncanny degree of clarity: You’ve got your fancy foie gras restaurants for the 1%, and then you’ve got an endless highway gridlocked with cheap garbage for the diabetic masses. Trumpville. Nothing in between.

And what would be in between? As Food & Wine’s Kat Kinsman tweeted about the president, “Do you think that he has ever even once in his life eaten at a restaurant that is not either fancy white tablecloth or fast food? Anywhere at all in the middle? I am trying to picture it and cannot.” Barack Obama may’ve dined at Estela and Cosme, two spots that we at Esquire recently celebrated on a list of the most significant restaurants of the decade, but restaurants like Estela and Cosme, restaurants that (it could be argued) contribute to the cultural hum of a city as much as museums and concert halls do, appear to be invisible and indecipherable to the man whom Spy magazine once famously described as a “short-fingered vulgarian.”

There has been a restaurant revolution afoot in the United States for decades now, a revolution that stretches all the way from Chez Panisse in Berkeley to The Grey in Savannah, Georgia, and which has hinged on breakthrough moments such as the publication of Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential in 2000 and the arrival of pioneers like Momofuku Noodle Bar in 2004, and which has gradually spread outward to cities like Cleveland and St. Louis and Indianapolis and Cincinnati. It is a revolution that has transformed lives and neighborhoods. On two Esquire trips to Seattle, I have made a beeline for the Ravenna neighborhood to see what chef Edouardo Jordan has been up to: dinner at his JuneBaby on one trip, drinks at his Lucinda Grain Bar on another. On both visits, I wandered around the corner to check out the vintage vinyl on sale at M&L Records & Models, and inevitably I spent some money there. “It's the wine shop on the corner,” Jordan recently told me in an interview. “It's the little breakfast place. It's the coffee shop. It's the old-school record store. It's all these little shops. It's the antique shop just one block away that all these people are finding out about because JuneBaby is in that neighborhood.”

Great restaurants turn sleepy corners into hubs of activity. From city to city, the restaurant revolution has been a revolution in consciousness at the same time that it has been a revolution in foot traffic.

And that revolution is officially over. It came to a stark and nauseating halt on Friday the 13 in March 2020. A virus put countless independent restaurants into a coma. It’s agonizing to think that thousands of those restaurants, many of them on the brink of fostering new transformations in new places, might finally be killed off by the culture wars.

But to quote Kurt Vonnegut, a son of Indianapolis: “So it goes.”