SEATTLE—Let's say you want to whisk across a city's downtown at a pace somewhere between walking and taxiing, and you're not interested in bus waits or looking like a dork on a hoverboard. How about a bike? How about a bike that you can pick up on practically any street corner, then leave behind in the same fashion when you're done?

That's the promise of not one but two bike-sharing efforts (Spin and LimeBike) that launched in Seattle this week. They differ largely from another former Seattle bike-sharing program, Pronto, in that they don't require any official docks. Take a bike; leave a bike. It's the two-wheeled equivalent of app-powered, car-sharing services like Daimler AG's Car2Go and BMW's ReachNow, only with a much cheaper rate of $1 per half hour of use.

Upon hearing about these services launching in my town, I got excited. Hop from place to place with shared bikes and my phone? Cool! But a few days of intermittent use—and some very odd encounters—have cooled my pedaling heels.

Helmet laws? What are those?

-

This is the first Spin bike I rode. Some bikes had their front and rear lights turn on while riding, but some of mine (including this one) did not.

-

Scan that QR code with the Spin app to start paying and riding.

-

Another QR code look. I suppose if you wanted to just start paying for this bike and messing with a Seattlite, you could do that with this photo. It's your money.

-

Baskets on both Spin and LimeBike bicycles are fixed to the direction of the wheel, not the handlebars. I personally hate that choice. Feels very disorienting when I turn the handlebars but the basket stays fixed.Sam Machkovech

-

A look at the rear wheel's locking mechanism.

-

Another look at the lock, and a better shot of the kickstand, which can be pushed in once you use the app to unlock.

-

Press on this to lock your bike and end your trip at any time.

-

More tire shots.

Pronto launched in Seattle in October 2014 with a goal of connecting a select few Seattle neighborhoods via bicycle hubs. Once you reached a hub, you could either wave a pre-paid membership card ($85/year) or pay for one-day or three-day passes, and then the system would spit out a loaner helmet and unlock a bike. The catch: you had to get your bike to another hub within 30 minutes of starting your ride or you had to pay additional fees, no matter what pass you were using. This is similar to bike-hub programs in cities across the United States, with the exception of the helmet-dispenser system required by King County law. (It started as an "honor code" system, but Pronto's helmets turned into a separate rental when helmets mysteriously stopped being returned.)

Steep pass prices, uneven hub deployment, and the constant need to shuttle bikes back to certain hubs (especially at the tops of hills) doomed Pronto from the start. The city-funded program bled cash and was canceled in March of this year. This was followed by the city green-lighting a new permitting system which would allow operators to dump bikes in the streets that have their own sign-in, sign-out systems embedded—so long as its users obey King County helmet laws and park the bikes in legal spots on sidewalks.

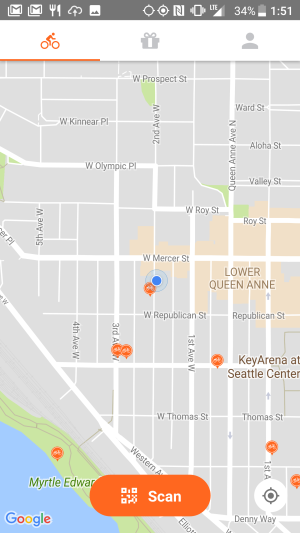

Thus, Seattle's new services, Spin and LimeBike, work in almost exactly the same fashion. Walk up to an official bike in either service (glaring orange or lime green, respectively) and use its app to scan the QR code on its seat. An audible wheel-unlocking confirms that you can ride, and then you are automatically charged $1 for every 30-minute interval you're using the bike. When you're done, find a legal sidewalk spot to leave the bike, then manually press the rear-wheel locking mechanism, and your ride is over.

The first issue with bikes on both Spin and Limebike is that they, uh, don't come with helmets.

Both apps repeatedly remind their riders to obey King County helmet laws, but while each service's bikes include a prominent basket attached to the front wheel, that basket space is not used to mount a default, fits-some-heads helmet as a backup option. I got to chat with Spin co-founder and president Euwyn Poon about this, and he expressed confidence that Seattle riders will bring bicycle helmets to their workplaces on the off-chance that they might want to hail a shared bike on a given workday. He added that the company planned on handing out free Spin-logo bike helmets throughout the city in its opening days. I asked how sustainable that was, compared to putting a locking mechanism for a helmet on the basket, and he opined that he hadn't thought of my idea.

As if on cue, this response was followed by one of the first-ever Spin riders whizzing past Poon's press event on one of the company's signature orange bikes... without a helmet on.

The bike is supposed to be right here

I was not invited to any formal LimeBike event, but I was able to sample one of its bikes, along with a few Spin bikes, parked along downtown Seattle sidewalks during the course of a week. (LimeBike appears to have a slower rollout, which the Seattle news hounds at Curbed report is an intentional strategy on their part.)

Both work as advertised, with QR codes in pretty much the exact same spot along with very similar bike designs and locking mechanisms. (LimeBike plays little bits of music when it locks or unlocks, if you're wondering.) Both companies' bikes sport three-gear systems, with LimeBike geared a little bit lower... but if you try to go up any of Seattle's hills, you're in for a bad time. This is a sticking point for a grand total of 1,000 bikes being rolled out between the two companies in the pilot Seattle program. Right now, the distributions are focused on the dense neighborhoods of Belltown (essentially, downtown, with tons of office buildings) and Capitol Hill (a younger neighborhood in identity crisis thanks to an influx of Amazon hires and condos-and-retail development).Both locations are marked by insane hills in the east-west direction, and that's not great news for a pilot program that combines heavy bikes and the added, uneven weight of built-in locks. To prove that out, I hopped off a Spin bike, began running down a hill while holding the bike, then slammed on its brakes. The rear wheel fishtailed wildly to the left just as I expected, thanks to how the lock is mounted, and I reproduced this fishtailing five more times.

My first testing bike on Spin also had a broken gear-shifter. I had to hold it firmly with one hand to keep it in first gear; otherwise, it would ratchet up to second gear, and I discovered this on a relatively steep incline while riding alongside car traffic. I had to ride a few blocks before I could safely pull off the road. (No other bike I tested with either service had this same issue, thankfully.)

-

Your first load of the Spin app tells you parking a bike is this easy. But...

-

...once you actually start paying for a bike, you are told a few rules.

-

Okay, six feet from what? Doorways?

-

What if there's a bike rack on a sidewalk corner, though?

-

What is that X-makred image indicating, exactly? Don't park next to... election booths? Bus stops?

-

How close can you be to curb ramps or driveways? Spin isn't clear, and LimeBike's "Zendesk" rules list is even less clear.

I took this opportunity to park the bike, but I'd already forgotten the rules and suggestions for parking that flashed when I first scanned my bike's QR code (and these don't pop up upon a ride's conclusion). Many Seattle blocks don't have installed bike racks, and that means parking a free-floating bicycle is a question mark of a task, even for people like me who regularly ride around Seattle. I have included the screenshot gallery above to show you the confusing info I received.

After an hour of coffee and snacks, I walked back out with my apps in hand to pick up another bike. LimeBike said it had nothing in my location, Spin suggested one bike a few blocks away on its map. However, as I walked toward a street I don't normally walk along, I realized its orange bike icon was not on a standard street but in an alleyway. On one side of the demarcated spot was a post office's loading dock. On the other was an apartment complex's parking lot. I didn't see a bright, orange Spin bike in either spot. Instead, I saw a woman curled up beneath the shade of a concrete structure. She heard me, looked up, and grunted.

Try as I might, I couldn't learn my lesson. The next day, after a successful and uneventful LimeBike ride (rode a few blocks from a haircut to a lunch), I walked toward another marked Spin bike, and it, too, led me to an alleyway with no bike in sight. Here, there were two people who clearly didn't want me walking past them, huddled up against an alleyway wall with cell phone cords and duffel bags in their hands. I'm pretty sure they didn't work for Spin; I didn't stay long enough to ask. (The whole thing reminded me all too much of last year's Pokémon Go crime waves.)

After these encounters, I decided to see how easy it'd be to mess with Spin and LimeBike by picking up parked, locked-up bikes and carrying them around. One of the Spin bikes beeped at me when I did this, perhaps thanks to a motion sensor, but one LimeBike and two Spin bikes did not beep. In one case, I carried a Spin bike toward a giant door and faked like I was going to throw it over. I didn't, but nobody noticed or cared. (I did this in part because Manchester's bike-sharing programs have suffered from ne'er-do-wells tossing shared bikes into the drink—which is a relatively easy crime to get away with, since the bikes can be picked up without logging any credentials in.)

Already flat?

When the bikes worked as advertised, I loved the middle-ground mobility they afforded me. I was able to shed 10-15 minutes off a few even-slope saunters, either between engagements or on my way to a far more efficient bus home (as opposed to needing to hop a few transfers). And I was happy to spend a measly buck each time. But I never once felt like dragging a bike helmet along, and the programs' likely target for widespread adoption—tourists—most certainly won't, either.

However, without electric bikes in the fleets, many of Seattle's most obvious biking routes are 100-percent off-limits. Even for those with thighs of steel, they still have to deal with the added burden of these services' heavy bikes. But the city's more gradual slopes and grades tend to favor commuters who are probably better off having a dedicated bike of their own. The other issue is that anybody without a smartphone is out of luck—and we'll have to wait and see if LimeBike's plans to create cash kiosks ever bear fruit.I could see Spin and LimeBike revitalizing certain Seattle corridors with an easy path to quick, 20- and 30-block trips. But without massive fleets outside the hilly downtown corridor or working solutions to King County's bike laws, the services right now look more like ways to burn through venture capital cash than sustainable, thought-out answers to Seattle's transit problems. When I interviewed Spin's president, I was told that the company did not study any bike-use heatmaps or interview citizens about what they wanted in a bike service. Instead, Poon told me he had friends test some bikes in his home city of San Francisco (assumedly in its less-hilly neighborhoods) and the incredibly flat town of Austin, Texas.

Bike sharing via apps has a technological component, sure, but there's an important data component to city planning that these companies will need to focus on to survive as truly sustainable services—not to mention wholly private ones that don't necessarily have long-term plans or quality-of-life priorities.

reader comments

230