The Sindhis of Shanghai: how an Indian diaspora cracked China

From the old Silk Road to the new one, there is one community of traders that has proved particularly successful. But then, perhaps they have an advantage: ‘Business runs in our genes’, they say

Daryanani, Lalwani, Malpani, Chatlani, Chandiramani. No matter where you might come across a Sindhi, their distinctive surnames make them easy to spot. The same is true even when they anglicise their first names, as they often do, in an effort to integrate in a foreign land, and Haresh becomes Harry and Kishan turns into Kenny. Although they remain unmistakably Sindhi, it is this ability to adapt that has seen this community, whose origins go back to Sindh province in Pakistan, succeed.

Today, the Sindhis of Shanghai and the neighbouring Yangtze River Delta are engaged in a wide range of businesses, from trading in apparel, textiles, daily use household products and plastics to machinery, pharmaceuticals, electronic products, and more. Most Indian traders outside Shanghai are in Yiwu, Keqiao, and Ningbo in Zhejiang province.

Yiwu, which lies about 100km from the provincial capital, Hangzhou, is easily the most famous of the three. Described as “the world’s largest wholesale market of general merchandise”, by the United Nations, it is a magnet for traders from around the world. At more than five million square metres, the Yiwu International Trade Mart is massive, spreading across the city centre, a one-stop destination for wholesale buyers of consumer goods. On a recent visit, ahead of India’s festive season, nearly everything needed to celebrate an Indian festival – including Hindu deities – was on sale in bulk.

Keqiao, the textile hub of China, is a county-level district within the Shaoxing municipality with a permanent registered residents’ population of 725,800 – and a migrant population of 876,000.

According to “Indians in the Chinese Textile City: Middleman Traders in Upgrading Economy”, a research paper published by Cheuk Ka-kin for the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford, about 5,000 Indians have established intermediary businesses, brokering fabric trade deals for overseas buyers.

Lost in Cuba: China’s ‘forgotten diaspora’

Labelled “Little India” in China, the transformation of Keqiao “from a local Chinese textile market to an international textile export centre” is credited to these Indian traders. A Hindu temple and a gurdwara stand side-by-side in the heart of the district, managed by a single Indian Hindu priest who looks after both places of worship. Ningbo, which lies on the shore of the East China Sea, is also coming into its own with a port that is second only to Shanghai in terms of annual cargo throughput.

If we smell a good business opportunity we will move anywhere

Ranked the 21st most competitive city by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the major economic drivers in this coastal city are petrochemicals, electrical machinery, telecom equipment manufacturing, IT, and port-related industry. Average annual growth has been more than 7 per cent over the past five years. Most Indians here source from Chinese manufacturers for buyers overseas. A few have ventured into manufacturing, but these are more likely to be partners in a joint venture and serve as the marketing arm of the enterprise. Still others are diversifying and investing in restaurants with long-term plans of staying.

The Sindhi ability to spot business opportunities is legendary, and they seem particularly adept at negotiating and deal making. “Business runs in our genes,” is a common refrain. “We are a business-minded community. We basically deal in business. If we smell a good business opportunity we will move anywhere,” says Girish, the restaurant owner in Yiwu.

Shanghai-based Prakash Chatlani, however, does not see this as being unique to his community. Says Chatlani: “The Jews, Arabs, and other diaspora groups are equally enterprising. These communities were often displaced and had to make a go of it in faraway lands to succeed. They have had a history of moving around to make money, just like the Sindhis. Their enterprising spirit has a long history. The Sindhis were among the earliest group of Indians to set up ventures abroad; their association with China dates back to the early 1880s.”

The community’s northernmost outpost in China was in Tianjin, where most were employees of companies headquartered back in Sindh, with a few family-run businesses.

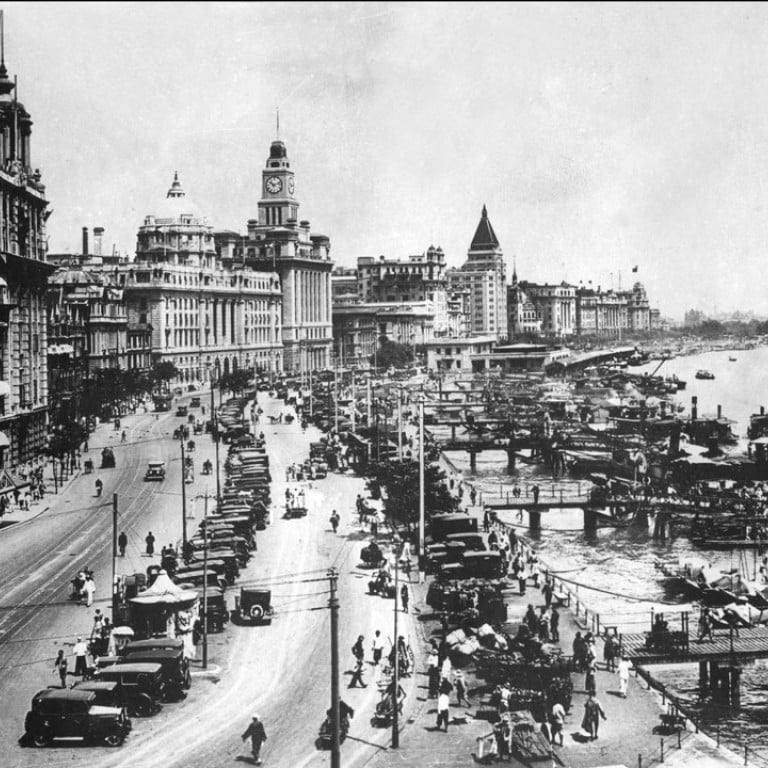

After the first world war, the community expanded its network to Shanghai, trading in silk products, thanks to Sindh’s proximity to the Silk Road.

According to historian Claude Markowitz, of 40 to 50 foreign firms listed as silk exporters in 1934 Shanghai, seven were Sindhi firms. This shows they commanded a significant share of the silk leaving Shanghai, which handled the bulk of China’s exports in this field.

One factor behind their growth as an entrepreneurial class is linked to an unfortunate chapter in South Asian history. The birth of Pakistan in 1947 sparked one of the largest migrations in human history, and with Sindh province located within the newly formed Muslim Pakistan, Sindhi Hindus led the exodus.

Wang Gungwu, the scholar who helped the West understand China

The loss of their homeland, stories of partition, and the resulting hardships have shaped the Sindhi identity. Keqiao-based Sanjay Rajpal says: “Hindu Sindhis were forced to flee their homes at the time of partition. They left behind everything. They had to start from scratch wherever they went. Everybody had to make a new life. The enterprising spirit comes from those days also.”

It’s a view shared by many. “Everybody earned money after 1947,” says Manoj Makdani, a trader in Yiwu. “We started from scratch. You can say that Sindhis are self-made.”

Markowitz writes that the Sindhi network grew and diversified rapidly in part because of the tendency of firms to split – due to factors such as family divisions and managers setting up their own firms, resulting in significant growth over four or five decades.

The Sindhi business presence in Shanghai is not as large as it is in Yiwu, Shaoxing, or Guangzhou, says Prakash Chetlani. Most live in Shanghai with their families for the cosmopolitan lifestyle and modern luxuries. Many have their core businesses in Shaoxing or Yiwu and commute often between these cities and Shanghai. In terms of Sindhi business families, there are no more than 40 to 50 companies in Shanghai.

Sindhis can be found in almost all economic corridors of the world. The “textile Sindhis” started off in Japan, South Korea, and Dubai when Korea was a textile powerhouse. They moved to Keqiao when China became the manufacturing hub, arriving not just from Pakistan, but from Africa and Latin America.

In a study of Indian and Chinese immigrant communities, author Jia Haitao claims most Indians living in Guangzhou are successful businessmen, “among whom the Sindhis are the most outstanding”. “The Sindhi people are usually compared to Chinese businessmen from the Wenzhou and Chaoshan areas because they are perceived to be frequent world travellers and born businessmen”.

Mahesh Rughani says: “After coming from Japan, Dubai and Korea, we struggled with the lifestyle here. Keqiao is a relatively new township … just over 15 years old. After 6pm, there is nothing to do here.” And then there is the language. “We couldn’t go anywhere without a translator. When we brought our families down, they didn’t like it. There are larger issues of health care and schooling. But we adjusted and settled down eventually. There were just 35 of us in 2001. Now there are around 2,000 Indians.” Among them are 500 Sindhi families.

Younger Sindhis face many challenges. In a market crowded with suppliers, it is not easy to convince global buyers of their reliability. Many of them come from difficult circumstances. They have to succeed – going back is not an option. “A Sindhi may work for somebody initially but he will always open his own business at some stage of his life. Sindhis will become small traders, shop owners, or businessmen, but they are all hooked on business,” says Haresh “Harry” Manek of Yiwu.

As they traverse the world looking for business, might they settle in China? It depends. “We are here long term, but not permanently. As long as we can make money here, we will stay. If there’s a better option or opportunity elsewhere, we will move on,” says Rughani. “Just like we did before.” ■

Excerpted with permission from ‘Stray Birds on the Huangpu: A History of Indians in Shanghai’, published by Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing Company, edited by Mishi Saran and Zhang Ke