On Tuesday, NASA announced that its chief of human spaceflight, Doug Loverro, had resigned after just six months of working at the space agency. This news, coming just eight days before NASA's first launch of humans in nine years, has rocked the civil aerospace community and kicked up a flurry of rumors.

This post will attempt to assess what we know, and what we don't know, about his departure and what it means for the space agency's human spaceflight programs moving forward.

Why did Doug Loverro resign?

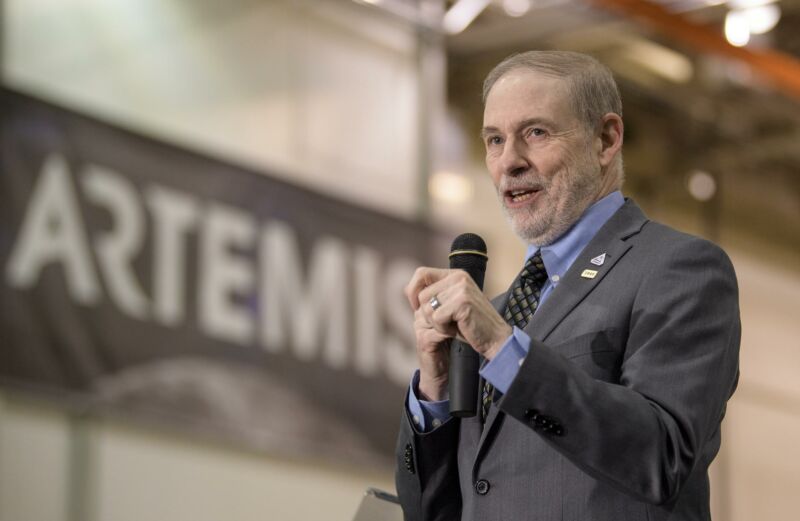

He made an error during the procurement process of the Human Landing System, during which NASA selected bids from Blue Origin, Dynetics, and SpaceX to build lunar landers as part of the Artemis Program. In his resignation letter to employees on Tuesday, Loverro admitted he made a "mistake" earlier this year. Multiple sources have suggested that he violated the Procurement Integrity Act.

It's worth noting that on March 25, 2020, NASA's inspector general announced an audit of "NASA’s acquisition strategy for the Artemis missions to include landing astronauts on the Moon by 2024." It seems plausible that this audit may have involved some action taken by Loverro.

So what did he do?

Neither Loverro nor NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine are speaking directly on this question, but we can make some educated guesses. Loverro's number one job when he was hired to replace Bill Gerstenmaier was to get humans to the Moon in 2024. Full stop. That was his remit and he took it seriously.

Loverro was also known to like "integrated launch," which means that he wanted to launch a complete lunar lander on a single rocket, rather than pieces of the lander on commercial rockets, to be assembled in orbit around the Moon. He judged this approach to be too complicated. And—here we're saying the quiet part out loud—the reality is that none of the three Human Landing System contractors selected by NASA are likely to be ready by 2024. Traditionally, at least, 4.5 years is just far too short of a time to design, develop, test, and build a deep-space vehicle that must go down to the Moon's surface and back.

So Loverro was under the gun to get humans on the Moon by 2024, he had concerns about most of the bids, and he favored integrated launch. This means Loverro likely favored the design of Boeing's bid for a Human Landing System, which entailed launching an integrated lander on a "commercial" Space Launch System rocket. It seems reasonable to assume that Loverro may have been pushing Boeing to come up with a more competitive bid. (After the awards were given to Blue Origin, Dynetics, and SpaceX, the agency's "source selection statement" indicated that Boeing's bid did not make it past a preliminary round of consideration).

When the inspector general found out about this, it likely precipitated Loverro's resignation.

How did the inspector general find out about this?

That's a very good question.

What might Boeing's reaction have been to not winning a lunar lander contract?

That's a very good question.

What were Loverro's true motivations?

Everyone I've spoken to believes that Loverro's motivations were pure in the sense that he was legitimately trying to get NASA to the Moon in 2024. But as one source said late Tuesday, "Speeding in good faith is still speeding." It does not appear that Loverro favored one contractor over another for political or financial reasons.

Rather, it seems that Loverro truly believed that launching an integrated lander on the SLS rocket was the only path that had any chance of putting NASA astronauts on the surface by 2024.

Does this affect the SpaceX Crew Dragon launch?

Probably not. In Associate Administrator Steve Jurczyk and in Loverro's deputy, Ken Bowersox, NASA has the leadership it needs to give the Crew Dragon mission final approval. In fact, if Commercial Crew Program Manager Kathy Lueders signs off on the mission, that will carry a lot of weight.

We'll know more after Thursday's Flight Readiness Review meeting for this launch, of course. But right now, people close to the mission remain relatively confident that the launch continues to track toward its original May 27 date. This is a testament to the hard work by NASA and SpaceX.

So Loverro's departure has nothing to do with SpaceX?

It seems not—at least directly.

What does this mean for Artemis?

This is a tougher question. The program is already racing for time, so any delays to moving forward with the lunar lander contracts would set Artemis back further. As of Tuesday, no protests—Boeing and the other bidder who did not receive a contract, Vivace Corp, had a right to object to NASA's final decision—had been filed since the lander awards were announced on April 30. Work is continuing with the three winning bidders.

That's a positive for NASA, but it's going to need a lot more funding in the coming years to make Artemis a reality, and that's where Congress comes in.

So where will Congress come in?

It is not clear what role, if any, Congress may have played in the departure of Loverro.

However, the chair of a House subcommittee that oversees NASA, Kendra Horn of Oklahoma, tweeted on Tuesday, "I am deeply concerned over this sudden resignation, especially eight days before the first scheduled launch of US astronauts on US soil in almost a decade. Under this Administration, we’ve seen a pattern of abrupt departures that have disrupted our efforts at human space flight."

Based upon her previous comments and her role in authoring HR 5666, Horn appears to favor Boeing's plan for an integrated lunar lander launched on a commercial SLS rocket. Boeing has other allies, too, particularly in the US Senate where Sen. Richard Shelby chairs the Appropriations Committee.

It seems clear that Bridenstine is going to have a lot of questions to answer when he goes to Capitol Hill to seek funding for Artemis—whenever that occurs in this era of COVID-19 and virtual meetings.

Is there any animosity between Bridenstine and Loverro?

There does not appear to be. People at NASA headquarters seem to be pretty shaken up by Loverro's sudden departure. These were not crocodile tears.

What do you think will happen?

We are only seeing part of the picture here. Ultimately, the White House and Congress are going to demand answers for this, and Boeing's anger at being left out of the Human Landing System awards may drive some of the response. It would not surprise me to see Boeing receive some kind of landing system award in the future to smooth all of this over.

One thing is sure: Jim Bridenstine's already difficult job as the head of NASA has just gotten more difficult. Perhaps he is facing a Kobayashi Maru test?

reader comments

344