The first time I touched my father was the day I cut his hair. Bill sat very still with his back to me, rigid and upright on a stool, a towel tied around his throat, and remained very quiet while I trimmed the white tufts behind his huge ears with kitchen scissors. My fingertips could feel the warmth of his neck. His creased skin was much softer than I had expected. It had always looked like roughly hewn granite. As I finished cutting the last strand, I lowered my hand so that my fingers brushed his wrist. It was the only time in my life that I remember touching him. Two days later, he died.

Children take sides, whether they mean to or not. From an early age, I had sided with my mother, who was bookish and lonely. My father was a hard Tory who believed so strongly in being independent that he refused to accept anyone’s help. Even when he was out of work, Bill would not go on the dole because he considered it immoral to do so. Only layabouts accepted handouts. His mantra was: “When you have family, you don’t need anyone else.” But we didn’t even have family – we were just people living under the same roof.

It seemed to me that my father was scared of living. Once he gave me a warning. I was holding a torch in place while he attempted to re-thread fuse wire in its ceramic block, and had momentarily lost concentration. “One day, when you’re grown up,” he angrily told me, “all the lights will go out and you won’t know how to repair a fuse, and the blackness will close in around you and there will be nothing you can do about it but sit in total darkness, where anything can happen.”

He believed that if you couldn’t do everything by yourself, you were weak and deserved to fail.

Bill’s beliefs weren’t mine, and we fought so much that it seemed likely that he might attack me. I was imaginative, creative, impractical – a cuckoo in the nest. How, he wanted to know, would I ever find suitable employment? This was in the 70s, times that were not suited to imagination. The social framework of the past was being destroyed, and no one knew what would replace it. Bill was convinced that if we all just kept our heads down and worked harder, things would come right. But I knew he had lost his job once before, and things hadn’t come right at all.

As we couldn’t afford to renovate our terraced house, Bill would try to do everything by himself – or worse, would get me to help him, which spelled certain doom. He would tell me to put away my notebooks and force me to hold bits of hardboard covered in Bostik and G-clamps, but my attention always drifted. No job was ever properly finished, and it seemed I was somehow to blame.

I wasn’t frightened of my father; I didn’t understand him. I felt him to be a coward, and he gradually diminished in my eyes.

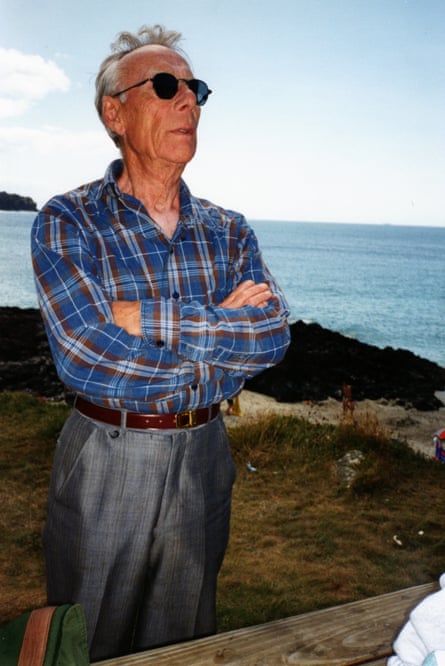

For his part, Bill turned me into “the topic we never mention”. After the war, the English had developed a deep suspicion of anything artistic. Art was feminised as something that would soften and damage masculinity. Books needed to be solid, improving and factual, and I wanted to be a writer. Bill was disappointed in me. A man who always looked immaculate in his grey suit, white shirt, grey silk tie and polished black Oxford toecaps – he did not own jeans or plimsolls – and even wore his suit and tie on the beach.

My dreams of a university education evaporated when I saw that I would have to get a job and ease the family’s finances. I went knocking on the doors of advertising agencies, and was offered a placement as a copywriter in a Regent Street company, on the condition that I learned to type and painted my own office. Say what you like about the 70s; it was never hard to find work in London.

I had thought this would ease tensions at home and that my father would be pleased, but he was furious. It was not that I had shown initiative and escaped, but that I had so easily achieved my ambition without any effort at all. When I went back to the family home, he refused to speak to me. I couldn’t simply stop going there because to do so would have punished my mother, so I continued to return and made matters worse with each fresh visit.

When my father realised that his sullen, accusatory silences were having no effect on me, he extended them to my mother, so that the house became a virtual tomb. The situation worsened with explosions of temper and destruction that caused my mother to call the police, although she would never have considered anything as drastic as divorce. I couldn’t understand what was going on, and had no way of putting the situation right.

My father was not a cruel man by any means. He was trying to find his way through life without accepting advice or financial support from anyone, including his own family. Once, he hid behind a door when a friendly neighbour came to call. Nobody in our house believed in self-help, therapy or self-awareness. No one would have dreamed of checking for signs that something might be wrong. The idea of mental wellbeing was either frowned upon or ridiculed as being unmanly, a waste of time and money.

The darkening situation affected my younger brother, who avoided being left at home and went to stay with friends. My mother became so isolated that I now realise she suffered the symptoms of a nervous breakdown, taking to her bed, unable to cope.

It struck me that something must have happened in our past to create this damage, so one evening after work I met my mother in a cafe and we talked, very awkwardly, about their marriage. Getting any information from her was like pulling teeth, but she described one event that finally provided a key.

My father had once worked in an innovative scientific unit and had been destined for great things. When the unit was offered funding in Canada, it was assumed he would go with them. But I was just about to sit my exams and teachers had advised my mother not to uproot me from London, as I was expected to do very well. My father had watched the unit leave without him. Shortly after, he changed careers and became bitterly unhappy in his new work.

Suddenly everything made sense. He had abandoned a decade of hard graft so that I could step straight into my chosen career without any kind of sacrifice or compromise. Meanwhile, he had lost his status and his purpose. Lines of regret etched themselves deeply into his face, until he looked as old as my grandfather. Bill had worked hard all his life and had been left with nothing to show for it but an ungrateful son. The family that should have been all he needed had failed him.

After I had my first novel published, my mother told me that, much to my amazement, he was proud of me. It wasn’t mentioned, of course, but the next time I went home I offered to cut his hair, and my offer was quietly accepted. I arranged the towel around his neck. As I began snipping, I thought of him standing in the darkness at 17, firewatching as phosphorescent bombs left trails above St Paul’s. He was imagining life among the stars, thinking of what might have been.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion