Why the 'China Model' Isn't Going Away

From Bangkok to Caracas, Beijing's style of authoritarian capitalism is gaining influence.

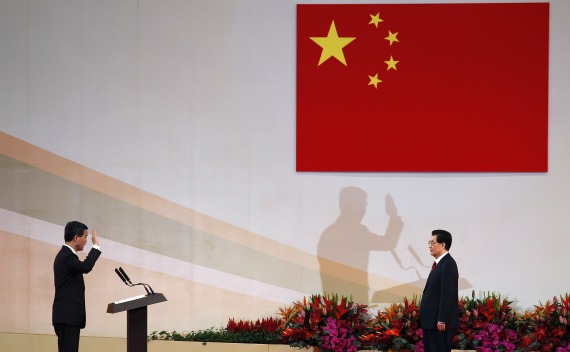

(Bobby Yip/Reuters)

Once considered an awkward, unsustainable blend of authoritarian politics and capitalist economics, China's growth "model" has shown impressive resilience in recent years. In this excerpt from his new book Democracy in Retreat, Joshua Kurlantzick explores why the "Beijing Consensus" has attracted so many admirers in recent years.

The attendees of the annual World Economic Forum in Davos are not exactly used to being told what to do. The Swiss resort draws the global elite: the highest-powered investment bankers, the top government officials and leaders, the biggest philanthropists, and the most famous celebrities, who gather each year to solve the world's most pressing problems and still have time for evening cocktails.

But in January 2009, the Davos crowd had to listen to a blistering lecture from a most unlikely source. The first senior Chinese leader to attend the World Economic Forum, premier Wen Jiabao, some thought, might take a low-key approach to his speech to the Forum. But at Davos, that genial grandpa was not in evidence. Months after Lehman Brothers collapsed, triggering the global economic crisis, Wen told the Davos attendees that the West was squarely to blame for the meltdown roiling the entire world. An "excessive expansion of financial institutions in blind pursuit of profit," a failure of government supervision of the financial sector, and an "unsustainable model of development, characterized by prolonged low savings and high consumption" caused the crisis, said an angry Wen.

Five years earlier, such a broadside from a Chinese leader would have been unthinkable. Though in the 1990s and early 2000s China had used its soft power to reassure its Asian neighbors and expand its influence in regions like Africa and Latin America, until the end of 2008 nearly every top Chinese official still lived by Deng Xiaoping's old advice to build China's strength while maintaining a low profile in international affairs. But in 2008 and 2009 the global economic crisis decimated the economies of nearly every leading democracy, while China surfed through the downturn virtually unscathed, though Beijing did implement its own large stimulus package, worth roughly $600 billion. China's economy grew by nearly 9 percent in 2009, while Japan's shrunk by over 5 percent, and the American economy contracted by 2.6 percent. By August 2010, China (not including Hong Kong) held over $860 billion in U.S. treasuries; when Chinese leaders returned to Davos the year after Wen's scolding of the West, they came not to chat but to hunt for distressed Western assets they could buy up on the cheap. In the downturn's wake, the crisis made many Western leaders tentative, questioning whether not only their own economies but also their political systems actually contained deep, possibly unfixable flaws. The economic crisis, said former U.S. Deputy Treasury Secretary Roger Altman, has left "the American model ... under a cloud."

These flaws appeared especially notable when compared with what seemed like the streamlined, rapid decision-making of the Chinese leadership, which did not have to deal with such "obstacles" as a legislature or judiciary or free media that actually could question or block its actions. "One-party autocracy certainly has its drawbacks. But when it is led by a reasonably enlightened group of people, as in China today, it can also have great advantages," wrote the influential New York Times foreign affairs columnist Thomas Friedman. "One party can just impose the politically difficult but critically important policies needed to move a society forward." Even John Williamson, the economist who originally coined the term "Washington Consensus," admitted, in an essay in 2012, that the Beijing Consensus appeared to be gaining ground rapidly, at the expense of the Washington Consensus.

As Western leaders, policy-makers, and journalists questioned whether their own systems had failed, Chinese leaders began to more explicitly promote their authoritarian capitalist model of development. After all, in the wake of the crisis many Western governments, including France and the United States, bailed out their financial sectors and many of their leading companies. These bailouts made it harder for Western leaders to criticize Beijing's economic interventions. In Beijing, a raft of new books came out promoting the China model of development and blasting the failures of Western liberal capitalism. "It is very possible that the Beijing Consensus can replace the Washington Consensus," Cui Zhiyuan, a professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing, told the International Herald Tribune in early 2010. Suddenly, too, the same Chinese leaders who in the early and mid-2000s still had played the role of the meek learner became, in speeches and public appearances and writings, very much the triumphalist teacher. In one article in the China Daily, one think-tank expert from China's Commerce Ministry wrote, "The U.S.' top financial officials need to shift their people's attention from the country's struggling economy to cover up their incompetence and blame China for everything that is going wrong in their country."

***

In previous reverse waves, eras when global democratic gains stalled and went backwards, there was no alternate example of development anywhere near as successful as China today; the Soviet Union claimed to be an alternate example, but it never produced anywhere near the sustained growth rates and successful, globally competitive companies of China today. In the early 1960s, another time of a reverse wave following the post-WWII democratization in Europe and parts of Asia, the only real challenger to liberal, capitalist democracy was the communist bloc.

Today, China -- and to a lesser extent other successful authoritarian capitalists -- offer a viable alternative to the leading democracies. In many ways, their systems pose the most serious challenge to democratic capitalism since the rise of communism and fascism in the 1920s and early 1930s. And in the wake of the global economic crisis, and the dissatisfaction with democracy in many developing nations, leaders in Asia, Africa, and Latin America are studying the Chinese model far more closely -- a model that, eventually, will help undermine democracy in their countries.

***

In recent years, the "China model" has become shorthand for economic liberalization without political liberalization. But China's model of development is actually more complex. It builds on earlier, state-centered Asian models of development such as in South Korea and Taiwan, while taking uniquely Chinese steps designed to ensure that the Communist Party remains central to economic and political policy-making. Like previous Asian modernizers, China in its reform era has devoted significant resources to primary education, resulting in youth literacy rates of nearly 98 percent; in many other developing nations, the youth literacy rate is less than 70 percent. Like other high-growth Asian economies, China also has created highly favorable environments for foreign investment. Yet in the China model, the Beijing government maintains a high degree of control over the economy, but it is hardly returning to socialism. Instead, Beijing has developed a hybrid form of capitalism in which it has opened its economy to some extent, but it also ensures the government controls strategic industries, picks corporate winners, determines investments by state funds, and pushes the banking sector to support national champion firms. Indeed, though in the 1980s and 1990s China privatized many state firms, the central government still controls roughly 120 companies. Among these are the biggest and most powerful corporations in China: of the 42 biggest companies in China, only 3 are privately-owned. In the 39 economic sectors considered most important by the government, state firms control roughly 85 percent of all assets, according to a study by China economist Carl Walter. In China the Party appoints senior directors of many of the largest companies, who are expected to become Party members, if they are not already. Working through these networks, the Beijing leadership sets state priorities, gives signals to companies, and determines corporate agendas, but does so without the direct hand of the state appearing in public.

What's more, in this type of authoritarian capitalism, government intervention in business is utilized, in a way not possible in a free-market democracy, to strengthen the power of the ruling regime and China's position internationally. When Beijing wants to increase investments in strategically important nations, such as Thailand or South Africa, it can put pressure on China's major banks, all of which are linked to the state, to boost lending to Chinese companies operating in those nations. For example, Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei, which is attempting to compete with multinationals like Siemens, received some $30 billion in credit from state-controlled China Development Bank, on terms its foreign competitors would have salivated over. By contrast, though the Obama administration wanted to drastically upgrade the United States' relationship with Indonesia, an important strategic partner, it could not convince many American companies to invest there, and, unlike the Chinese leadership, it could not force them to do so.

In short, the China model sees commerce as a means to promote national interests, and not just to empower (and potentially to make wealthy) individuals. And for over three decades, China's model of development has delivered staggering successes. Since the beginning of China's reform and opening in the late 1970s, the country has gone from a poor, mostly agrarian nation to, in 2010, the second-largest economy in the world. With the economies of leading industrialized democracies still suffering, today China, and to a lesser extent India, are providing virtually the only growth in the whole global economy.

Since 2008, not only top Chinese leaders but also people across the country clearly have become more confident about Beijing's place in the world. Some of this confidence is only natural, part of China reclaiming its position as a major world power. But some of the confidence comes from China's more recent rise during the global economic crisis, which put Beijing in an international leadership role far before its leaders expected. And, some of the confidence comes from Chinese leaders, diplomats, and scholars traveling more widely, and realizing that their democratic neighbors -- Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and many others that used to lecture China about human rights and freedoms -- actually are falling behind China's breakneck growth. "Chinese leaders used to come here and want to learn from us," one senior Thai official said. "Now it's like they don't have anything left to learn ... They have no interest in listening to us."

China's newfound confidence has manifested itself in many forms. When the Nobel committee awarded the 2010 Peace Prize to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, jailed in China for organizing an online petition calling for the rule of law, Beijing condemned Norway and other European nations, and applied intense pressure on European officials, and many from Asian nations as well not to attend the ceremony awarding his prize. Ultimately, several of the nations China pressured the hardest, like the Philippines, declined to send representatives to the Nobel ceremony.

A few months earlier, Beijing had applied similar pressure on European nations, this time to join with it in an unprecedented public call to replace the dollar as the global reserve currency. China followed up on its call by helping Chinese firms, and foreign companies, begin using the renminbi more readily in international transactions, as well as in funds based in Hong Kong. When, in the fall of 2011, European nations looked for saviors to their growing economic crisis, China stepped in. Chinese officials signaled their willingness to contribute as much as 100 billion euros to the European Financial Stability Fund, or possibly a new bailout mechanism set up by the International Monetary Fund. In Greece, China launched plans to invest billions in infrastructure, including its ports, while also repeatedly offering to buy up Greek debt.

Beijing has become more forceful in dealing with Washington, too, a forcefulness that can add to its appeal with developing countries, who've often looked for another major power, and particularly a power hailing from Asia, to balance their relations with the United States. When the Obama White House informed Chinese officials in the summer of 2009 that it, like every other recent American administration, planned to host the Dalai Lama for a private meeting, Beijing aggressively lobbied the White House not to meet the Tibetan leader. The White House acquiesced, and for the first time since the administration of George H.W. Bush, the Dalai Lama came to America without meeting the president, a huge victory for China. "There has been a change in China's attitude," Kenneth G. Lieberthal, a former senior National Security Council official focusing on China, told the Washington Post. "The Chinese find with startling speed that people have come to view them as a major global player. And that has fed a sense of confidence." Or as one current senior American official who deals with China said, "They are powerful, and now they're finally acting like it."

In 2010 and 2011 and 2012, China also surprised its neighbors by stepping up its demands for large swaths of the South China Sea, other contested waters, and regions along its disputed land borders. In the summer and fall of 2010, China reacted so furiously to Japan's decision to impound a Chinese fishing boat in disputed waters that it cut off shipments to Tokyo of rare earth materials, critical to modern electronics like cellular phones and fiber optics. Beijing also later clashed again with Japan over disputed islands, and has warned its neighbor Vietnam not to work with Western oil companies like ExxonMobil on joint explorations of potential oil and gas in the South China Sea. It has detained Philippine and Vietnamese boats, and claimed nearly the entire sea -- Beijing's claims extended nearly to the shores of the Philippines, hundreds of miles from China's territory.

***

This increasingly assertive Chinese diplomacy has alienated some other countries, particularly in Asia. Yet along with more forceful diplomacy, Beijing has started to proactively promote its model of development, and in some ways, its newfound confidence only adds to its global appeal, since other, smaller countries want to join forces with a clearly rising power. But even as China has become more confident, its leadership still recognizes that it cannot challenge American military power, at least not anytime soon. Despite boosting its defense budget by over 10 percent annually, China remains a long way from developing a global blue water navy, or expeditionary forces capable of fighting far from China's borders. Most years, the Pentagon's budget surpasses the defense budgets of all other major military powers combined. "We need to think more on how to preserve national integrity. We have no intention of challenging the US [militarily,]" admitted Major General Luo Yan, a senior member of the People's Liberation Army.

Recognizing that China remains decades from challenging the Pentagon, Beijing's leaders realize they can compete in other ways, such as by promoting their development model, and as other countries learn and adopt aspects of the China model, they will become more likely to align with China, to share China's values, and to connect with China's leaders. The economic crisis, Chinese economist Cheng Enfu told reporters, "displays the advantages of the Chinese model ... Some mainstream [Chinese] economists are saying that India should learn from China; Latin American countries are trying to learn from China. When foreign countries send delegations to China, they show interest in the Chinese way of developing."

By the early 2000s, China already had developed training programs for foreign officials, usually from developing nations in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia. These officials came to China for courses in economic management, policing, and judicial practice, among other areas. At the time, Chinese officials would not necessarily suggest China had an economic model to impart. But by the late 2000s, many of these courses explicitly focused on elements of the China model, from the way Beijing uses its power to allocate loans and grants to certain companies, to China's strategies for co-opting entrepreneurs into the Communist Party, to China's use of special economic zones to attract foreign investment over the past thirty years. One Vietnamese official who repeatedly has traveled to China for such programs noted how the style of the programs has changed over time. Now, he said, Chinese officials, far more confident than even ten years ago, would introduce the example of one or another Chinese city that had successfully attracted sizable investments, talking through how the city government coordinates all permits and other needs, and moves favored projects swiftly through any approval process. Central Asian attendees at Chinese training sessions noted how they increasingly learned about the Chinese judicial system, in which the Party has almost complete control, and then returned to their home countries, where their governments used similar types of control measures over their judiciaries.

Beijing also has built close political party-to-political party ties with several other developing nations. Increasingly, it has utilized these ties to promote its model of political and economic development. For at least two decades, Vietnamese officials have traveled to China, and have based many of Vietnam's development policies on China's strategies. More recently, Chinese officials have worked on development planning with leading politicians in neighboring Mongolia, which democratized after 1989 but where the public has become increasingly disenchanted with corruption and weak growth. Chinese officials also have co-operated with United Russia, the main pro-Kremlin party, whose leaders want to study how China has opened its economy without giving up political control. In 2009, United Russia held a special meeting with top Chinese leaders to learn Beijing's strategy of development and political power.

These efforts to promote a China model of undemocratic development build on a decade-long effort by Beijing to amass soft power in the developing world. Among other efforts, this strategy has included expanding the international reach of Chinese media, such as by launching new China-funded supplements in newspapers in many different countries, and by vastly expanding the reach and professionalism of Chinese newswire Xinhua. Today, according to its own figures, China's state-backed international television channel reaches over sixty-five million viewers outside the country. This strategy also includes broadening the appeal of Chinese culture by opening Confucius Institutes -- programs on Chinese language and culture, at universities from Uzbekistan to Tanzania. It has involved a rapid and substantial expansion of China's foreign aid programs, so that Beijing is now the largest donor to many neighboring nations like Cambodia, Burma, and Laos. An analysis of China's overseas lending, compiled by the Financial Times in 2010, found that China lent more money to developing nations in 2009 and 2010 than the World Bank had, a stark display of Beijing's growing foreign assistance. And the soft power initiative has also included outreach to foreign students, providing scholarships, work-study programs and other incentives to young men and women from developing countries. The number of foreign students studying in China grew from roughly 52,000 in 2000 to 240,000 in 2009.

Over the past decade, too, China has set up networks of formal and informal summits with other developing nations. At first, the summits offered China the opportunity to emphasize its role as a potential strategic partner and source of investment and trade. But over the past five years some summits, like those with Southeast Asian and African leaders, also subtly advertised China's model of development, according to numerous participants. Several Thai politicians who attended the Boao Forum for Asia, a kind of China-centered version of the World Economic Forum in Davos, noted that, in recent years, some of the discussions at Boao had shifted from a kind of general talk of globalization and its impact in Asia to more specific conversations about some of the failings of Western economic models exposed by the global economic crisis, and whether China's type of development might be less prone to such risks.

The soft power initiative also has involved a coordinated effort to upgrade the quality of China's diplomatic corps, replacing an older generation of media-shy, stiff bureaucrats with a younger group of Chinese men and women, many of whom are fluent in English and comfortable bantering with local journalists. One day, while working in Thailand, reporters saw the then-U.S. ambassador Ralph Boyce, appearing on a prominent Thai talk show. Boyce was known in the diplomatic community for his knowledge of Thailand and command of Thai; on the show, he spoke fluently and elegantly. Alongside him, the Chinese ambassador to Thailand also appeared, speaking fluent Thai and appearing right at home in the freewheeling television talk format. In one cable released by Wikileaks, even American diplomats stationed in Thailand admitted that Thai officials had become increasingly admiring of China and its model of development, and less interested in the American model.

***

Until the past two or three years, the China model appealed mostly to the world's most repressive autocrats, eager to learn how China has modernized its authoritarianism. But in recent years it is not just autocrats who have been learning from Beijing. China's soft power offensive has given it increasing leverage over democracies in the developing world, and made Beijing's model of development more attractive to leaders even in freer nations, places where there has already been some degree of democratic transition.

Since China's advocacy of its model of development is still relatively new, it will take years to see the full effect of its challenge to Western liberal orthodoxy. Still, one can see some initial effects in developing democracies. In Venezuela and Nicaragua, Beijing has ingratiated itself with the leadership, offering $20 billion in loans to Caracas in the spring of 2010, a time of economic downturn in Venezuela; China's loans helped Hugo Chavez perpetuate his government, even in the face of significant opposition. As China has gained a larger presence in nations like Venezuela, Chavez increasingly sent top diplomats and bureaucrats to Beijing to specifically examine China's strategies of development, and how they might be applied in Central or South America.

Similar shifts have taken place in Southeast Asia, where China's soft power, and its economic strength, has broadened its appeal, even when its military aggressiveness sometimes have hurt it at the same time. What's more, China has used its influence to push Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam , and Thailand to deport Uighurs, Falun Gong practitioners, and other political migrants fleeing China, as it has used its growing power in Nepal to push the Nepalese government to run back Tibetans fleeing China, even though Nepal has for years provided shelter to many Tibetans. And in Central Asia, where China increasingly conducts training seminars for local police, judges, and other justice officials, Central Asian officials say that Beijing has pushed them to use their judicial systems to arrest and deport Uighurs as well.

Across Southeast Asia, in fact, China's model has gained considerable acclaim. "There are, of course, no official statements from [Southeast Asian] countries about their decisions to follow the Beijing Consensus or not," writes prominent Indonesian scholar Ignatius Wibowo. "The attraction to the Chinese model is unconscious."

Still, it is possible to quantify this "unconscious" appeal. Having analyzed surveys of political values in Southeast Asia going back a decade, Wibowo concludes that people in many Southeast Asian share a willingness to abandon some of their democratic values for higher growth, and the kind of increasingly state-directed economic system that many of these countries had, in their authoritarian days, and that China still has today. Southeast Asian nations "have shifted their development strategy from one based on free markets and democracy to one based on semi-free markets and an illiberal political system," Wibowo writes. "The 'Beijing Consensus' clearly has gained ground in Southeast Asia." Indeed, by examining the political trajectory of the ten states that belong to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, going back more than a decade,

Wibowo found that with only a few exceptions, each country's political model, examined through a series of political indicators, has moved in the direction of China and away from liberal democracy over the past decade, largely because these nations had watched China's successes, and contrasted it with the West's failures. Many Southeast Asian leaders and top officials were implementing strategies of development modeled on China's, including taking back state control of strategic industries, recentralizing political decision-making, and using the judicial system as, increasingly, a tool of state power, and re-establishing one-party rule -- all changes that undermine democratic development. Supporting his claims, the most recent Economist Intelligence Unit's survey of global democracy, which analyzes nearly every nation in the world, found that the global financial and economic crisis "has increased the attractiveness of the Chinese model of authoritarian capitalism for some emerging markets" -- which has added to democracy's setbacks.

In Thailand, for example, growing numbers of politicians, bureaucrats, and even journalists favorably contrasting China's undemocratic model of government decision-making with Thailand's messy, and sometimes-violent pseudo-democracy. In the past five years, as Thailand's urban-based middle-class, and its favored political parties, have taken back dominance of politics, they have increasingly adopted tools of control similar to China. These have included creating an Internet monitoring and blocking system like China's and skewing the judiciary, through judicial appointments and "instructions" to judges from the royal palace, so that judicial rulings weaken potential opposition parties and ensure the dominance of the ruling party. Although not every element of Thailand's political change was explicitly modeled on China, of course, many Thai officials noted how the use of the judiciary, the control of the Internet, and other political tools did have some inspiration from China.

Even outside Southeast Asia, in other parts of Asia, China's gravitational pull and its soft power have had an influence on democracies. Overall, concluded political scientist Yun-han Chu, who studied Asian Barometer surveys about East Asians' commitment to democracy, "authoritarianism remains a fierce competitor of democracy in East Asia," in no small part because of the influence of China's ability to foster economic success without real political change, providing an alternative model that is clearly visible to other East Asians, who travel to China, work with Chinese companies, buy Chinese products, and host Chinese officials. As he notes, China will, in the coming years, become the center of East Asian trade and economic integration, giving it even more power. "Newly democratized [Asian] countries [will] increasingly become economically integrated with and dependent on non-democratic countries," Chu writes.

To be sure, China's model of development, just like democratic capitalism, suffers from numerous flaws. These flaws potentially include an inability to hold corrupt or foolish leaders to account, a lack of checks on state power, and a reliance on benign and wise autocrats for the China model to work, which is hardly a given -- for every Deng Xiaoping, the politically savvy and foresighted architect of China's economic reforms, one could find ten Mobutu Sese Sekos or Kim Jong Ils. Rising inequality within China, between the favored urban areas and the less well-off interior rural provinces, also threatens to unhinge China's economic miracle, either through growing waves of protests by rural dwellers or massive popular migrations that unleash instability. Already, China has shifted from one of the most equal -- if poor -- nations in Asia in the late 1970s to one of the most unequal societies, today, in East Asia. But for now, China has seen relative success in its attempt to quietly impart its model of development to other nations.