Same Performance, Better Grades

Academic achievement hasn't improved much, so why are college-goers getting higher GPAs than ever before?

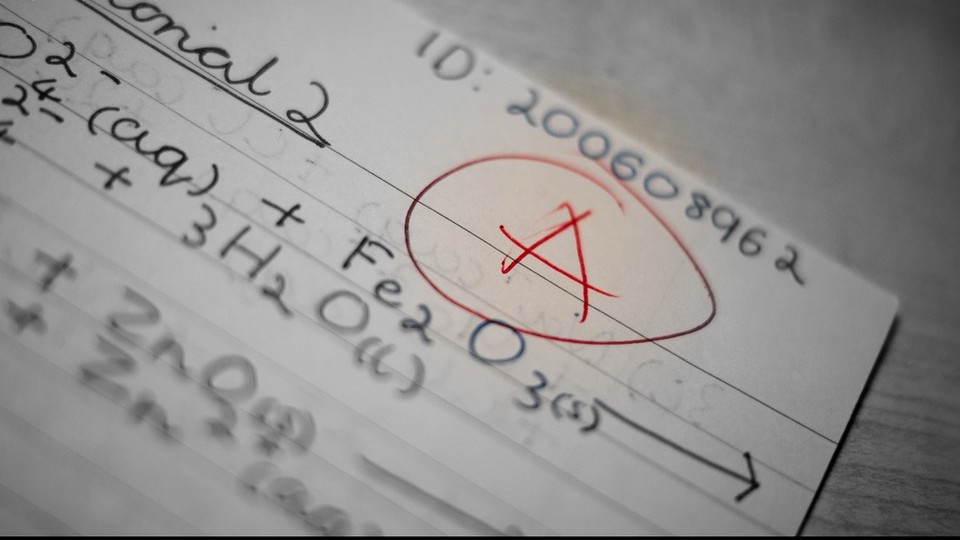

It’s raining As in America’s higher education system, and not necessarily because students are particularly smart. In fact, many of them probably don’t deserve the high marks they’re getting. They have grade inflation to thank.

That inflation is rapidly spreading to higher education institutions across the country. Despite stagnant academic performance, more students than ever before receive higher grades than they should. The trend is raising ethical questions and marks a 180-flip from a few decades ago, when the opposite problem—grade deflation—plagued many colleges.

“Students aren’t getting smarter," said Stuart Rojstaczer, a writer and former science professor who calls himself the country’s “grade inflation czar.” “They aren’t studying more. When they graduate they are less literate. There’s no indication that the increase of grades nationwide is related to any increase in performance or achievement.”

Rojstaczer’s website, GradeInflation.com, compiled GPA data from more than 230 American universities. These studies corroborate the inflation, showing that the growth rate started to escalate following the Vietnam War.

Average college GPAs in 2006 were much higher in they were in 1930, according to a study of more than 160 colleges and universities that was published in the Columbia University-based publication Teachers College Record. Rojstaczer co-authored the study with Christopher Healy, who teaches computer science at Furman University and said such inflation can ultimately undermine students’ achievement.

“If you give everybody an A, either people are not going to take it seriously or those who do take it seriously might get the wrong impression,” Healy said. “When students receive grades, they’re receiving feedback on how well they did in their courses, if they put in an equal amount of effort [in] each one. And [if] they receive higher grades in some subjects, they logically come to the conclusion that they are good at certain things. It wouldn’t normally occur to them that they happened to receive a grade that was out of line."

Grade inflation is more prevalent now at private institutions than it is at public ones, according to the study. The mean GPA for both private and public schools in the 1930s was 2.3, or a C+. That number for both types of institutions increased at the same rate until recently. Today, the average GPA at private universities is 3.3, a B+, while that at public colleges is 3.0, a B.

A 2013 study conducted by the University of North Texas’s Department of Economics might help explain the forces behind recent grade inflation, suggesting that several key players could be responsible for the overall trends. For one, the study shows that classes in certain subject areas are more prone to inflation than others. English, music, and speech courses experienced higher rates of inflation compared to those in math and chemistry, for example.

Class size also appears to be a factor. One theory is that departments with smaller student-faculty ratios have a greater tendency to exaggerate grades because those instructors have less job security than their colleagues in larger-scale college divisions. “Let’s say my department finds out that we give far fewer As than some other department that we’re competing against for students,” Healy said. “That may give an incentive for faculty to increase their grades.”

The type of degree program could also influence the extent to which professors overstate students’ grades. Inflation was more prevalent among Ph.D. departments, for example, than it was among lower-level programs, according to the study, which looked at data between 1984 and 2005. The instructor’s gender could be a factor, too: Inflation is much higher among female educators than it is among their male counterparts.

Meanwhile, student evaluations could incentivize instructors to give their pupils higher grades than they deserve in an effort to “buy” higher evaluation scores, the study says.

Whatever the cause, an analysis of average test scores—as well as literacy levels—over time confirms that rising GPAs are not a reflection of increasing academic achievement. Though standardized exams are certainly flawed measurements of intelligence, comparing trends in scoring with those in grades is revealing: Unlike average GPAs overall test scores have remained relatively steady over time, demonstrating that the grade inflation is artificial. Graduate literacy has also kept constant; the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy found that average literacy hasn’t changed since 1992.

Students in some areas may actually be performing better academically, which could help explain the inflation, but they can’t account for national upward grade trends. On a national level, student quality hasn’t improved enough to justify the inflation.

Ultimately, grade inflation has severe consequences. Not only does it make it difficult for employers to vet the caliber of an applicant, but it also misleads students, who often use their grades as benchmarks to help diagnose their strengths and weaknesses. “If everybody gets an A or a B, then grade point average doesn’t carry as much as information as a signal to potential employers or graduate schools,” Michael McPherson said, an economics professor at the University of North Texas. Grade deflation—which still affects some institutions, including Boston University—has its repercussions, too.

The epidemic of grade inflation—and deflation—brings America’s higher education system under further scrutiny, particularly because many administrators and professors appear to condone, or at least accept, the grade manipulation.

“We’re not in an era of strong, moral ethical leadership in higher education,” Rojstaczer said, “Leaders are obsessed with national reputation and the size of their endowment and not very concerned about the quality of education.”