Oakland, California’s Lake Merritt is the oldest wildlife refuge in North America and home to dozens of bird species. Within its 3.4 miles of shoreline, it’s not uncommon to see great blue herons and snowy egrets soaring over flocks of bobbing ruddy ducks. But over the past year, another bird—well, a Bird—has joined the other lake denizens. Just in October, cleanup crews fished out of the lake more than 60 electric scooters, made by Bird and its competitor Lime as well as lesser-known comers like Scoot and Wind, according to James Robinson, executive director of the Lake Merritt Institute. Robinson recently met with representatives from Lime and Bird as well as Oakland’s Department of Transportation to address what he’s calling a “crisis” for the lake.

Oakland’s not the only place you’ll find troubled waters. In Portland, Oregon, so many scooters have ended up in the Willamette River that some disgruntled Portlanders made a website, scootersintheriverpdx.com, that documents just what its URL promises: How many scooters have been thrown into the Willamette River? Portland police have responded to several reports of people throwing the scooters into the river. In Los Angeles, maintenance workers have reported seeing the electric conveyances tossed into the Pacific Ocean around Venice Beach, where Instagram shots of half-sunken scooters abound. In Spokane, Washington, two Lime scooters were found in the Spokane River in October, and Lime has fished its scooters out of the Trinity River in Dallas, too. In Indianapolis, council member Zach Adamson found one in the Broad Ripple Canal and lamented, “It’s not OK to throw scooters in our waterways.” In San Francisco, it’s become routine to see a Bird or Lime scooter washed up along the rocky shores of the Bay.

Bird and Lime pitch their devices as environmentally friendly alternatives to cars, since they’re electric and are attractive options for short trips within cities. But the companies have also taken a rapid approach to expansion, sometimes launching in cities without regulators’ permission. Even when local governments do sign off on the scooters—which users can rent with an app, and leave on any sidewalk when they’re done—it’s not clear how closely the companies are working with cities to ensure these new streetscape additions aren’t too nettlesome. It’s anyone’s guess why so many of these vehicles are ending up in lakes and rivers, but one reason might be that some people just find them enraging, or at least annoying enough to hurl into the nearest body of water. But that hasn’t slowed down the scooter-makers: Both Bird and Lime have raised hundreds of millions in venture capital funding, poising the companies to continue expanding across the country.

In places such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Raleigh, North Carolina, officials have moved to cap the number of scooters allowed on their streets. In Oakland, scooter company officials have met with the city multiple times and heard complaints from the nonprofit Lake Merritt Institute, which has argued that its staff should be compensated for their time and efforts to remove scooters from the lake. “While the companies did not directly address the problem of scooters dumped in the lake, they said that they would retrieve scooters within 24 hours when notified,” read the September Lake Merritt Institute newsletter following a meeting with Oakland’s Shared Mobility Committee. Robinson said in a more recent update that actions from that meeting haven’t stopped scooter-dumping.

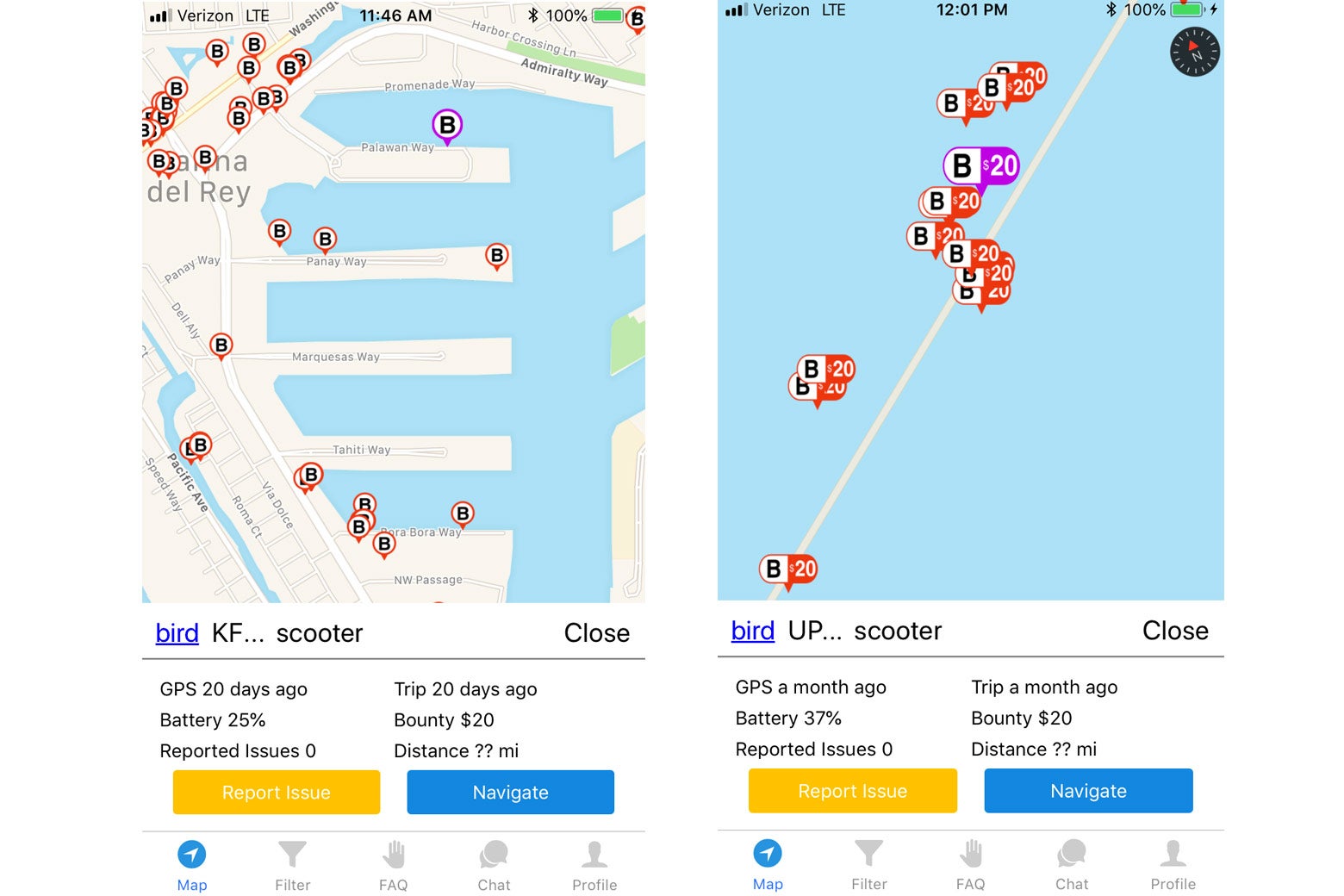

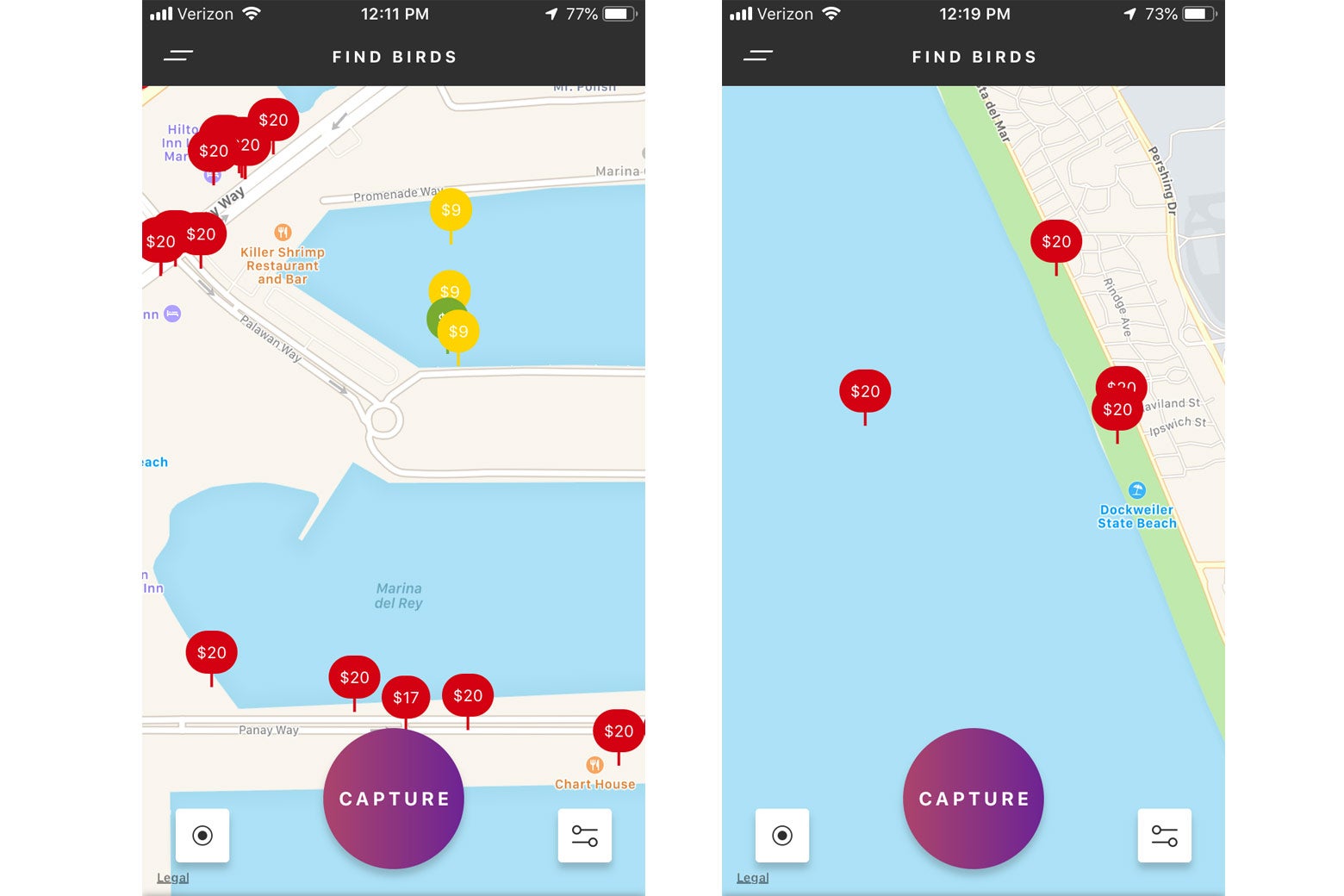

Anyone can sign up to be a charger for Bird and its competitors, which means collecting scooters on the street at night and charging them in your home, for which the companies compensate you. The toolkit these chargers use provides a useful window into the bodies-of-water problem. Using the apps’ maps, as well as third-party sites like Scooter Map, they can see where there are scooters in need of more power. And those locations often include lakes and other waters. One Bird charger in Los Angeles shared screenshots showing six scooters in the water in the Marina del Rey area and off Dockweiler State Beach.

Dozens more scooters (mostly Birds) in Marina del Rey appear to have been left right on the water’s edge for days—some for months, according to Scooter Map. The maps show where the scooters were when their GPS last picked up a signal, which means that they could very well be in the water and pinged their apps right before getting tossed in. One Bay Area–based charger I interviewed, Nicholas Abouzeid—who has been collecting and charging scooters for Lime, Bird, and Scoot—says that he hasn’t seen scooters on the map “that are blatantly in the ocean because the GPS itself sucks, placing the scooter at random places and because companies clear out the ‘ghost’ scooters after the GPS goes offline.” Ghost scooters may show up on the map but aren’t actually there or aren’t retrievable—perhaps because they are already in a lake.

When I asked one of the people behind Scooters In the River why he began documenting scooters thrown into the Willamette River, he said it was “the environmental impact, plain and simple. The Willamette River has been abused enough, it doesn’t need any additional toxic compounds from decomposing scooter batteries.” The maker of the website, who asked to remain anonymous, hasn’t heard from any of the scooter startups.

But scooter companies are very aware of the problem. “We have our local ops team patrolling [Lake Merritt] for scooters on a daily basis,” Lime spokeswoman Mary Caroline Pruitt wrote in an email, adding that the company acts immediately if it receives a report of a scooter in Lake Merritt. Lime has also implemented a “no parking zone” around the lake to prevent passersby from throwing the scooters in the water—meaning the scooters won’t be able to end their rental session in the lake’s immediate vicinity.* Pruitt added that Lime plans to donate to the Lake Merritt Institute to help compensate its cleanup efforts. Bird says it investigates all instances of vandalism and works with law enforcement to take “appropriate measures” when a scooter has been damaged, like by being thrown in a lake. Neither company commented on larger plans they have to prevent their scooters from polluting waterways in cities where they operate.

It’s hard to know exactly how damaging a deluge of scooters is for a body of water and its denizens. Dozens of scooters regularly being thrown in a lake “is certainly going to be incredibly disruptive to ecosystems,” says David Cwiertny, a professor of environmental engineering and director of the University of Iowa’s Center for Health Effects of Environmental Contamination. “What’s going to make this problem hard to address is that there are unanticipated consequences.” Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, the kind that power laptops, smartphones, and electric scooters, commonly contain nickel that can leach out into the environment over time, Cwiertny said. The Environmental Protection Agency warns that in high concentrations, nickel is a dangerous pollutant for aquatic life.

The case for putting more scooters in more cities, like bike-share systems before them, is clearly attractive: Give people more ways to get around—particularly ones that can fill the gaps of public transit—and they’ll probably use cars less. But it’s hard to know what the prescription is to address the vandalism that seems to afflict these vehicles. Even when these scooters don’t end up abandoned in waterways, many of them end up trashed, either because they weren’t built for such sustained use or because vandals rip them to pieces. One company, Scoot, which was permitted to operate scooters in San Francisco in October, told the Wall Street Journal that within two weeks of launching, more than 200 of the 650 scooters they introduced had been stolen or irreparably destroyed.* The need to constantly re-supply these fleets should, at minimum, complicate the narrative of low environmental impact that these companies pitch. Still, for now Bird and Lime appear to have cash to spare, and are using a chunk of it to absorb the cost of the vandalism and fishing their devices out of rivers, oceans, and lakes—even if their efforts have thus far failed to stop the problem.

What’s a concerned, marine life–loving human to do? “Even if one claims that scooter vandalism is a protest against the intrusion of VC-backed startups into our communities, it still doesn’t explain what good putting one in a lake or river will do,” Scooters In the River’s creator told me. “There’s a billion better ways to fight the man.”

*Correction, Dec. 14, 2018: An earlier version of this article misstated the timing of when Lime implemented a no-parking zone for scooters around Lake Merritt.

*Correction, Dec. 11, 2018: An earlier version of this article misidentified the company Scoot, which spoke to the Wall Street Journal about issues with stolen and vandalized scooters.