The Mummy, released last month (June , 2017) in the USA and Canada, is the latest in the long-established franchise that started in 1932. Tom Cruise stars in the latest reboot playing the charming boy-scoundrel Nick Morton who, while stationed in Iraq, seizes the opportunity to hunt for antiquities.

For this review, the Nile Scribes do what Egyptologists do best: talk about ancient Egypt. All too often, films like this one become the only interaction the general public has with ancient Egypt, something even more true since the Egyptian Revolution in 2011, when international tourism to Egypt has been at an all time low.

Unfortunately, we only get to see the ancient Egyptians in brief flashbacks: princess Ahmanet with her father the king, and a couple quick glimpses into the royal palace. Historians have rolled their eyes at the ethnically inaccurate casting of ancient Egyptians since the beginning of filmmaking, including such decisions as Yul Brynner as Ramesses II, Sigorney Weaver as Queen Tuya, and Gerard Butler as the god Seth. The original mummy in the 1932 film, Boris Karloff, was a British actor.

For this retelling, princess Ahmanet is played by Sofia Boutella, an Algerian-French actress, and her father King Menhepetre is played by Selva Rasalingam, a British actor of partly Tamil descent (of South India and Sri Lanka). These casting decisions are perhaps the most ethnically accurate for ancient Egyptians in the mummy franchise, to date.

Our mummy antagonist is the Egyptian princess Ahmanet, the first female mummy of the franchise. Her name means “the hidden one” and is obviously in homage to the name of the goddess Amunet, consort of the god Amun. There were no doubt numerous historical Amunets but our villain does not appear to be based on a known person. Her father, King Menehptre, whose name might mean “the established one is the steering oar of Re,” is also not a historical person, but his name might be a phonetic conglomeration of the throne and birth names of Mentuhotep Nebhepetre (II), pharaoh of the Eleventh Dynasty and founder of the Middle Kingdom.

The source of the “mummy’s curse,” and Ahmanet’s powers, is the Egyptian god Seth, the god of chaos and disorder, deserts and desert animals, foreigners and foreign lands. Through Seth, she is endowed with tattooed symbols (that are oddly not Egyptian hieroglyphs) and a number of fearsome powers. She controls swarms of rats, birds, and camel spiders (a non-venomous arachnid that lives in desert biomes like Iraq); drains the life out of living persons with a kiss; and raises an army of undead crusaders with a single command in ancient Egyptian (weben, meaning “to rise”). While Seth does not actually make a physical appearance, he is represented as the god of death throughout. The Egyptians would have understood him as the negative counterpart to Osiris, whom he killed only for Osiris to return as god of the underworld. An equation as god of death, though, reflects more Western attitudes with connections to Lucifer or Satan.

Fact-checking the Ancient Egyptian elements

The legendary dagger of Seth with a ruby on its hilt is central to Ahmanet’s plans. In the story, Crusaders stole the dagger and took it to England; the ruby was buried with a crusader and the dagger was hidden away in a mediaeval reliquary. Rubies, not native to Egypt, did not come into use in Egypt until the Roman period (or over 1,500 years after the plot of the film), when the stone was imported from as far away as India. Egyptians did believe, however, that materials had symbolic properties and could have positive or negative connotations.

The movie begins with a (fictional) quote from the “Prayer of Resurrection”:

“Death is the doorway to new life.

We live today. We shall live again.

In many forms shall we return.”

Many examples of prayers inscribed by individuals on stelae or ostraka (sherds of broken pots) were often directed toward a specific deity and survive from ancient Egypt, but the writers of The Mummy have not used an authentic example of such prayers.

Despite this, quite a bit of the film’s dialogue is spoken in the ancient Egyptian language, which means that Ahmanet’s lines were translated from English into Egyptian for the film (we scanned the credits for the Egyptologist(s) who consulted on the film, but either they have not been credited or we missed them). Egyptologists take much of their understanding of the language’s pronunciation from Coptic, the last phase of the Egyptian language and a language still used liturgically today in Coptic churches. Students of Egyptology learn to read the signs aloud, but our pronunciation varies from school to school based our tutelage.

Pro-tip: they’re called hieroglyphs not hieroglyphics. ‘Hieroglyphic’ is an adjective, while ‘hieroglyph’ is a noun that means “sacred carvings” in Greek. Shame on our fictional film archaeologist for the mix up.

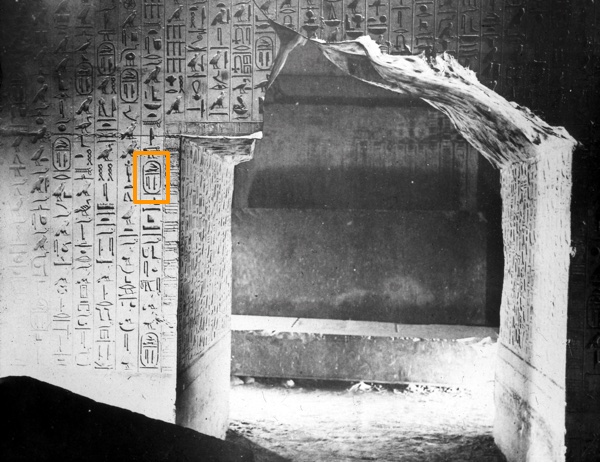

Our first glimpse of ancient Egypt in the film is a bizarre (and very un-Egyptian) wall carving of hieroglyphs discovered in the crusaders’ catacombs. While we only get a brief look, a cartouche of King Unas (last king of the Fifth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom) is visible in the hieroglyphs, if you’re quick enough to try and read them. Unfortunately his cameo is entirely arbitrary – we learn later that our mummy Ahmanet was a New Kingdom princess during her lifetime. Confusingly, Jenny (Annabelle Wallis), the film’s “archaeologist for hire,” dates the New Kingdom (1,550-1,069 BC) to 5,000 years ago, or around 3,000 BC, a period that most Egyptologists ascribe to the Early Dynastic period.

However, Ahmanet’s story does seem to be a nod to Hatshepsut, famous Queen-turned-King of the New Kingdom who became co-regent with her stepson Thutmose III, when her husband, Thutmose II, died. Hatshepsut’s solution was more cunning than Ahmanet’s, who simply makes a pact with the god Seth for eternal life and power. She promises to aid Seth in his desire to rule with her in human form and then kills her father, his queen, and the newborn prince. (After a few years of ruling alongside her stepson, Hatshepsut declared herself king, even changing her image to that of a man’s.)

Curiously, in the very beginning of the film, Egyptian priests pour mercury into Ahmanet’s coffin and lower it into a “ritual well” filled with mercury (the archaeologist explains that the Egyptians believed the material wards off evil). Ancient Egyptians, of course, never did use the commodity in this capacity; however, red mercuric sulphide (Cinnabar) is present in Egypt and was used to create a bright red pigment, or mixed with other metals as a compound (especially gold and silver) as early as the 5th century BC.

Ahmanet’s Cruel Fate

As punishment for murdering her father, princess Ahmanet is mummified alive and taken far away from Egypt to be buried outside the pharaonic lands. The ancient Egyptians believed that the foreign lands were under the tutelage of the deity, Seth, another (unseen) antagonist of the film. While there isn’t any evidence of an ancient Egyptian royal burial outside of Egypt, the filmmakers’ adoption of this idea finds corroboration in Egyptian attitudes to being buried abroad in Egyptian literature. In the well-known Story of Sinuhe, the protagonist laments the possibility of dying outside of Egypt and feels redeemed, when Pharaoh welcomes him back to pharaonic lands to be buried here.

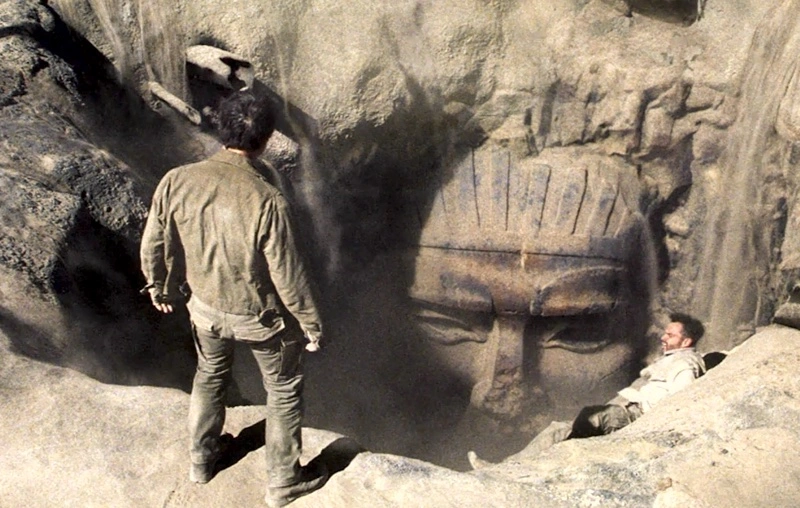

The location of her burial under an Iraqi village seems striking. Egyptian tombs are normally located on the west bank of the Nile (as Egyptians believed that the entrance to the underworld is found at the place where the sun sets) in close proximity to the river’s floodplain. The village is not located near a body of water – a fact perhaps emphasising her wrongdoing and offence of the gods. The tomb’s entrance and a monumental face, uncovered after an airstrike on the town, marked the location of a huge underground cavern. The face wears a nemes-headdress (a sign of royalty) and evokes a loud scream. The style and overall carving of the face does adopt some Egyptomanian aspects, though like Ahmanet’s coffin it could have used more Egyptian influences.

At the bottom of the cavern a shaft was filled with mercury and was encircled by four statues of Anubis, their faces pointing toward the centre. This is obviously a way for the deity to ‘guard’ over the tomb, ensuring the evil stays contained. Egyptian tombs are famous for their many books of the afterlife that are inscribed on the walls: a normal burial would encourage the deceased to be born again through these texts. Ahmanet’s burial lacks these texts entirely, instead, she is watched by the protective gaze of Anubis.

Portraying the Middle East

The opening sequence is a chilling look into how a colonial power asserts its quest for antiquities in far off lands. The overall sentiment of the opening is a disrespectfully light-hearted portrayal of the destruction and looting currently happening in the war-torn landscape of Iraq (Iraqi forces are poised to liberate Mosul from the Daesh (ISIS) this month). Nick and his partner Chris Veil (Jake Johnson) possess a map that tells them a cache of treasures is to be found in a northern Iraqi village, appropriately named Haram, or “forbidden” in Arabic. As they run into the insurgents almost immediately after entering the village, they do not toy for long with the threat of the insurgents and call in an air-strike. The village is flattened, the insurgents leave, and the protagonists are at last in peace to claim the spoils and pillage Ahmanet’s tomb, declaring that they are not looters but “liberators of antiquities.”

The carelessness of our protagonists in approaching members of a different culture is enough to bring chills to the spine of the modern archaeologist. The field has long struggled with the ever-changing regulations of the countries we work in; archaeologists were once allowed to export their finds back to their respective countries with only minor limitations. The film, perhaps unintentionally, gives a nod of approval to the many antiquities dealers or professional looters who combed through Egypt and the Middle East over the last few centuries, filling the coffers of many modern museums in the process. The situation is not helped with the stereotypical portrayal of sand dunes, village terrorists, and endless, seizable treasures – all elements we associate with the Middle East. The scenes were not even filmed in the Middle East, but within continental Africa in Namibia.

The Archaeology

The discovery of the ruby from Seth’s dagger’s by a construction crew in London who were digging railway tunnels gives viewers a realistic, if somewhat embellished, glimpse at one way antiquities and archaeological sites are commonly discovered in the modern era. Construction projects in all parts of the globe often reveal secrets of the past that have long been buried, especially in cities that have been continuously inhabited for centuries. Only months ago an aqueduct dating to the 3rd century BC was discovered in Rome during construction of a metro line.

Our biggest disappointment was just how little Egypt features in the film at all, which takes place entirely in Iraq and the UK (and filmed in the UK and Namibia). Moviegoers get a couple quick glimpses of a computer-generated Giza plateau, and a typical Hollywood-ified ancient royal palace in flashbacks of Ahmanet’s life, but otherwise, our Egyptian mummy finds herself in a C-130, medieval churches and catacombs, and the Natural History Museum in London (although wouldn’t the British Museum have been a more fitting place for her to wind up?).

If you’re looking for a heavy dose of ancient Egypt in your life this week, you might want to look elsewhere. But if you always wanted to see an Egyptian mummy command an army of zombie crusaders while Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde attempts to rid the world of supernatural evil, this is your film.

Did you see the movie? What did you think?

Our rating:

Interested in other Egyptological reviews of The Mummy? Check these out:

- “The Mummy reviewed by an Egyptologist: ‘Tom Cruise’s Late Egyptian is passable’”

- “A review of ‘The Mummy’: sex, death and inaccuracy”

Photos:

- Relief of Mentuhotep II from his tomb and mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari, Thebes (11th Dynasty) [07.230.2, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York] – LINK

- Looking toward the burial chamber within the Pyramid of Unas at Saqqara (5th Dynasty) [WikiMedia]

- An Osiride column from the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut from Deir el-Bahari (18th Dynasty) – [authors’ photo]

- The mummy gallery within the British Museum in London – [authors’ photo]

- Image from ‘The Mummy’ trailer posted on the Website of the Washington Post – LINK

- Image from ‘The Mummy’ trailer posted on the Website of the Washington Post – LINK

Fantastic. Both educational and entertaining. A great blog I’ll share with many. Makes one wish Hollywood writers would do some research before attempting fiction. Perhaps it would even improve their plot.

Great piece, and very informative. Thank you. Keep it up!