Grace Krause

abstract | Historical data from the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 shows that Chicago Chinese Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries deliberately constructed foodways as a method of mediation between themselves and a frequently unfriendly social landscape. In turn, white middle-class residents of the United States used Chinese American foodways to reinforce racial hierarchy. This research explores Chinese American identity through foodways, and foreign food as a contact zone where perceptions of race and ethnic identity have been negotiated. Chinese immigrants settled in Chicago with the rapid expansion of railroads by 1869, opening restaurants and laundries in a small enclave along Clark Street. Despite hardships, they learned to manipulate white perceptions of their culture to present an alternative way of living in the United States with the fair as a catalyst for change.

keywords | ethnohistory, Chinese Americans, World’s Columbian Exposition, contact zones, foreign food

Introduction

For Chicagoans, the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 has been so thoroughly incorporated into the cultural landscape that extant aspects have all but lost their historical meaning. The purpose of the fair was to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World and to present a global display of progress and progressive ideas with the United States at the center. Chicago’s selection as the site for the fair was a boon for a city then considered inherently uncultured, diseased, and dangerous.[1] The Museum of Science and Industry (formerly the Palace of Fine Arts), Jackson Park, and the Midway Plaisance are a few of the more conspicuous artifacts that remain. Organizer Frederic Ward Putnam originally intended the Midway Plaisance, an extension of the fair located on the parkway connecting Jackson and Washington Parks, to be a collection of serious exhibitions on world ethnography. Instead, it turned into an exposé on the exotic and novel, placing the so-called Other in the spotlight. Anthropologist and ethnohistorian Raymond Fogelson described it best as a “self-congratulatory orgy of ethnocentrism.”[2] The nature of the Midway’s exhibits created tension between the exploitative goals of the fair’s managers and the entrepreneurial attitudes of many of the participating groups.

Provoked by U.S. immigration laws that unfairly targeted Chinese migrants, the Qing government refused to send a delegation to the fair. Consequently, Chinese Americans and Chinese migrants living in Chicago decided to represent their heritage on the Midway, where they opened a café that sold Chinese and Anglo-American food as well as Chinese teas. At a time when food in the United States generated extensive debate, the Chicago fair was a pivotal event for white middle-class perceptions of foreign food. Chinese food, in at least some form, was present at the fair, available on the infamous yet popular Midway Plaisance. The Chinese Village served food and tea as entertainment, intentionally playing into the U.S. perception of Chinese people as exotic Others.

This essay discusses the role of Chinese food in Chicago through Chinese involvement at the fair and argues that the placement of the Chinese exhibit on the Midway created a contact zone that influenced white middle-class perceptions of Chinese culture through cuisine. Contact zones, as defined by literary scholar Mary Louise Pratt in her book Imperial Eyes, are social spaces in which disparate cultures come in contact with each other and interact on unequal terms.[3] Contact zones are created through colonial relationships: Pratt shows how travel writings by European authors during colonial periods produced foreignness for a European audience by describing their explorations of the world through the lens of imperial ideologies. While the subjects of Pratt’s book are mostly travel writers, her theories are widely applicable, including to the 1893 Columbian Exposition. As global migration and industrialization accelerated, white middle-class encounters with people from all over the world significantly increased in the period leading up to the fair.[4] Foreign food in the late nineteenth-century United States enacted a large-scale contact zone in which cultures mingled and clashed, pushing the boundaries of edibility.[5] Foreign food on the Midway represented an asymmetrical relationship among cultural groups where white fairgoers functioned as colonizers juxtaposing those groups as the Other, a static cultural foil by which to support their perceptions of race. Negotiation of group identity was not the sole purview of the colonizers in contact zones, however. Pratt describes how “colonized subjects undertake to represent themselves in ways that engage with the colonizer’s own terms” to assert their autonomy while maintaining the contact zone.[6]

Culinary adventurism—the negotiation of white middle-class identity through the consumption of foreign cuisines—became popular toward the end of the nineteenth century and helped Chinese food gain a platform in broader U.S. society during and after the fair. However, more than the desire for new taste experiences, the rise of culinary adventurism after the fair was a way to symbolically colonize China through consumption. The contact zone that formed on the Midway in 1893 persisted through the subsequent culinary adventures of the white middle class and the ongoing efforts of Chinese American culinary entrepreneurs.

Chinese Identity in Chicago

Chinese migrant workers started arriving in significant numbers to the mainland United States in the 1850s with the onset of the Gold Rush. Migrant workers predominantly identified as male and primarily came from southern China, particularly the Guangdong Province, commonly known as Canton in English. In addition to their culture and dialect, these migrants brought regional Guangdong food traditions to the United States, where the restaurant business was often a lucrative option. Food in Guangdong during this period was socially stratified, sophisticated, and influenced by international trade flowing through the region. The creation of popular elite dishes, such as shark’s fin soup, marked Guangdong both as economically prosperous and a place of great culinary innovation, although the poorer classes struggled with food shortages.[7] Everyday cooking methods employed extensive preparations, brief exposure to high heat, steaming, or a combination of boiling and steaming. Chinese migrants brought all of these methods to the U.S. and adapted them to new physical and social environments; they were often forced to make do with minimal ingredients and western-style cookware.[8]

Reasons for leaving China varied among migrants, but their desire for improved living conditions and quality of life was undeniable. Problems in China largely outweighed problems in the U.S., according to Chinese laborers and businessmen who left written records after their initial arrival on the West Coast.[9] Overpopulation, poverty, disease, famine, uncertain political conditions, war, and agricultural crises were some of the major factors contributing to migration.[10] Social mobility was difficult for the merchant class because of class discrimination. As commerce and industry began to accelerate in the 1880s, this stigma was partially removed, inspiring people from other professions to try their hand at economic ventures abroad. Migrants were not China’s poorest or least educated citizens. Many had already migrated, traveled widely in their home country, or experienced Western culture.[11] Historian Mae Ngai also emphasizes that migrants had often participated in wage labor before migrating: the Guangdong Province has been home to significant commercial industries in agriculture, textiles, and metals since the seventeenth century.[12]

As they migrated, Chinese men carried Confucian traditions of familial duty, although they were rarely able to physically bring their families with them. Confucianism dictated that men were responsible for the economic success of the family.[13] Most migrants hoped that success in the U.S. would allow them to return to China and their families. These men have been called sojourners, a term defined in this specific context by Chicago sociologist, Paul Siu, in the 1930s.[14] Return migration was available to about one-third of the sojourner population, and the rest chose to stay in the U.S. and send for their families when possible.[15] Sojourner identity in the U.S. was initially based on family or clan, with a gradual shift toward a broader Chinese identity in the late nineteenth century as the nationalist movement gained momentum.[16] Siu’s characteristics of sojourner identity also include “ethnocentrism and the in-group tendency” meaning the sojourners had pride in their heritage and sought to maintain it in their new location.[17] Chinese Americans also exhibited characteristics of a growing Chinese nationalist identity in the choice to participate in the fair and in the design of the exhibit.

After the initial flood of sojourners into the United States in the 1850s, white residents of the U.S. frequently opined in newspapers and other public contexts that they were taking all the jobs. During Reconstruction, the white middle class grouped Chinese laborers with formerly enslaved black laborers, perceiving both as morally degenerate and dangerous to Republican social and economic values.[18] The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad and closing of vast numbers of mines in the second half of the nineteenth century caused many Chinese laborers to switch to other jobs that had traditionally hired whites, heightening anti-Chinese sentiment on a national level.[19] The same racial prejudices directed at black and indigenous residents of the U.S. were extended to Chinese Americans—they were unfairly associated with uncivilized behavior, such as trafficking, opium use, gang violence, and unsanitary foodways, activities perceived to be connected to Chinatowns across the country.[20] Thus, federal legislation began to curb entry into the country and employment for Chinese migrants. Naturalization of Chinese people as citizens of the United States was prohibited in 1870. The Page Act of 1875 prevented Asian contract laborers, Asian women likely to engage in the commercial sex trade (all single women, according to the Act), and convicted criminals of any ethnicity from entering the United States. These laws, as well as mounting anti-Chinese sentiment, led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which was enacted to prevent most Chinese from entering the country for ten years. In 1892, the Geary Act extended the Exclusion Act and required all Chinese to carry resident certificates.[21] All these discriminatory acts of legislation caused the diplomatic relationship between the United States and China to deteriorate.[22]

Immigration laws created nearly insurmountable hurdles for Chinese wishing to move to the United States. The U.S. government only allowed men who could prove citizenship, or diplomats, students, and merchants across the border, making illegal entry the only option for many. The Chinese found and exploited a loophole in the immigration laws, which created a unique subgroup of immigrants called “paper sons,” men who claimed kinship with a registered Chinese resident of the United States.[23] Previous immigrants would register more children than they actually had on their official immigration paperwork and sell the extra slots. To aid in this process, paper sons would purchase family study guides to prepare for rigorous entry interviews.[24] Immigration officials were aware of illegal immigration but seemed to be unable to devise successful methods to prevent it.[25]

In spite of the prejudicial treatment of Chinese labor, immigrants as a whole were expected to uphold the economy of the United States through their labor on the soil and consumption of U.S. goods.[26] The U.S. briefly saw China as a potential new frontier, a hinterland with vast economic potential available to support U.S. expansion, which would also promote the spread of western ideologies, particularly in consumer practices and puritanical Christian ideologies.[27] Historian Matthew Jacobson has written that these conflicting anxieties about the role of foreigners in U.S. society during the nineteenth century were translated into one of two beliefs: that they could be helped along the path to civilization or that they were so hopelessly behind that it was unnecessary to treat them as equals.[28] The Chinese were most often sorted into the latter category.[29]

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Chicago became a more appealing environment for Chinese migrant workers in comparison to the West Coast. Many fled to the city hoping to escape anti-Chinese violence and rhetoric elsewhere in the country. Others followed the railroads to Chicago or intended to settle there due to social connections. By 1869, rapid expansion of railroads across the West brought the first sojourners to Chicago.[30] At the time of the Columbian Exposition, a relatively small but thriving Chinese American population operated restaurants, laundries, groceries, trade outfits, and other types of businesses, largely for the internal benefit of community members. The original Chinatown was located on the north side of the city, along Clark Street, between Van Buren and Harrison.

The Chinese population in Chicago increased from 172 in 1880 to 584 in 1890, three years before the opening of the fair.[31] At the time of the fair, City of Chicago officials estimated approximately 2,800 Chinese lived in the area with more still to be registered.[32] While these figures are drawn from the census, a precise count of Chinese in Chicago is impossible to tally. Illegal immigration, falsified family information, and low English literacy among Chinese immigrants during this time period suggest numbers that were likely higher than the official count.[33] In this article, I choose to include the published numbers to provide evidence of the fair’s impact on Chicago’s Chinese population. Still, the demographics remained predominantly male, with three percent or less of the Chinese population identified as female in the late nineteenth century.[34]

The Midway Plaisance

The golden age of world’s fairs began with the Great Exhibition, held in London in 1851. Fairs touted industry and progress as reasonable and desirable products of modernity, showcasing the cultures and technologies of all participating nations. The underlying reality of world’s fairs, however, was a supreme ethnocentrism buoyed by hierarchical constructions of race by whites. Large fairs became popular places to display human “zoos”—ethnographic collections of peoples perceived as inferior by colonial powers displayed in an enclosure with traditional housing, dress, and objects, often far removed from their native environments. These displays were thought to be educational and entertaining.[35] Organizers designed much of the Chicago fair with the goal of surpassing the Exposition Universelle (held in Paris in 1889). The Midway Plaisance directly responded to the human zoo and amusements of the Paris fair.

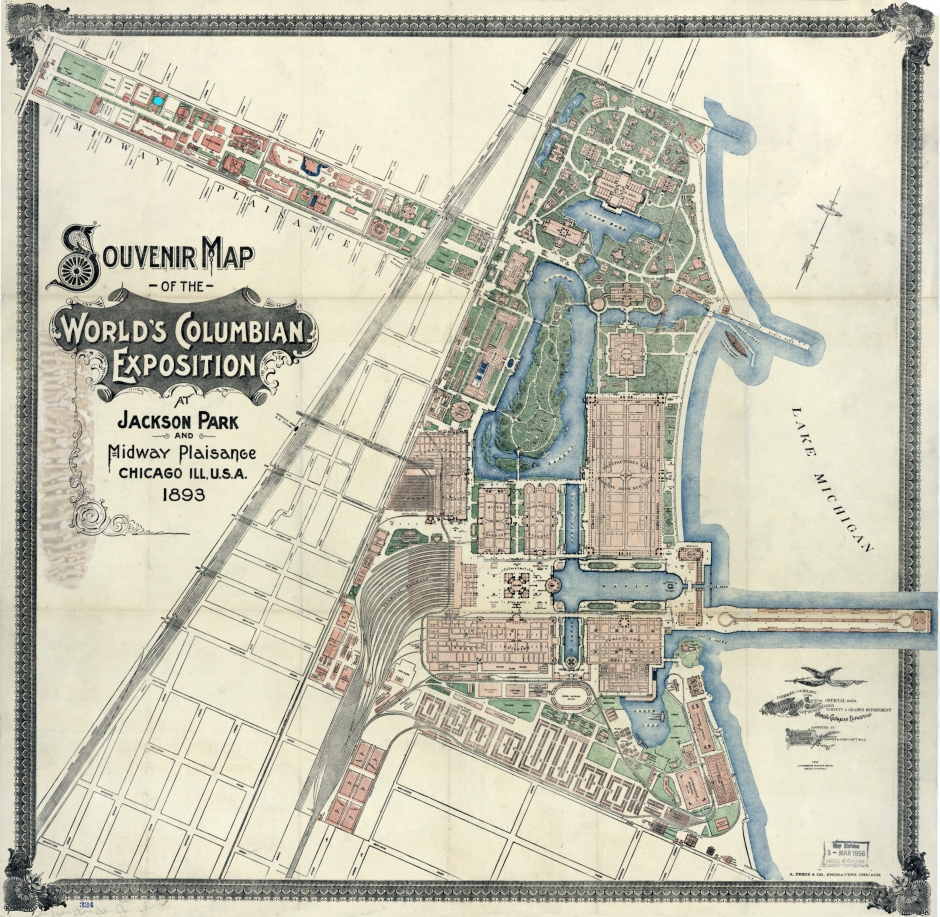

Currently known as 59th and 60th Streets, the Midway Plaisance was located directly west of the main fairgrounds (see Figure 1) and was originally conceived as a place for dignified ethnographic displays. Changes in management and serious construction delays plagued the Midway, and it did not open until almost two months after the official opening day, causing management to cut corners. Construction delays also increased management costs, so the organizers turned to amusement and spectacle, which were historically far more lucrative than educational exhibits at world’s fairs, to recover funds.[36]

The Exposition Universelle included a variety of ethnographic displays designed by anthropologists, although most of the groups featured derived from the African or Asian continents. For the Chicago fair, organizers invited anthropologist Frederic Ward Putnam to recreate Paris’s human zoo of so-called primitive peoples.[37] Sol Bloom, an entertainment entrepreneur from San Francisco who organized the Algerian Village for Paris, later replaced Putnam as the major decision-maker and manager for the Midway.[38] Although he remained the official director, Putnam was unable to control the activities on the Midway due to pressure from Bloom, and, consequently, it lost most of its educational intent.[39] Progressive-era scientists presented cultural progress according to color, from black to white, an approach to social evolution common among white residents of the U.S. in which skin tone and technology determined the level of civilization. White, and in the case of the fair, Anglo-American, civilization was perceived as the highest form, while blackness and African features were considered almost simian. Other skin tones fell somewhere between.[40] The White City, of course, held the elevated position of the ideal civilization, with its gleaming white structures and physical separation from the Midway.[41] Whether the various participants were acutely aware of this hierarchical ordering or not is unclear, as the majority of them did not leave written records of their experiences.[42]

In addition to ethnographic displays, Bloom conceived of the Midway as a place for fun of a less “wholesome” nature. Frederick Law Olmstead, the landscape architect who was instrumental in designing the fair, was adamant that the endeavor should contain an equal element of play and fun in addition to beauty and education. Bloom shared his interest in play and accepted Midway exhibits that were purely for the amusement or awe of the fairgoers, such the Ferris Wheel, captive balloon ride, and natatorium.[43] A writer for the Chicago Daily Tribune argued that the Midway was completely for fun and amusement with no element of education at all.[44] Novelty animal exhibits also appeared on the Midway, such as an ostrich farm and carnival displays of dangerous animals.[45] Though considered scandalous by late nineteenth-century white middle-class standards, Bloom included women performing dancing displays and vendors shouting enticing vocal advertisements in a variety of languages. Turnout at the fair’s opening in May was disappointing, but attendance improved considerably by the end of June. It is probably no coincidence that June’s impressive figures coincided with the opening of the Midway.[46]

The Midway lured visitors with the promise of being able to see something exotic. Newspapers like the Tribune were aware of the exotic appeal and used it to advertise and report on the exhibits. Guides to the fair published in the newspaper included descriptions of what the average fairgoer could expect to experience at the different exhibits and the types of foreign people they would be able to see. “Race Types of the World’s Fair” was one such guide, printed on July 30th after the Midway was in full swing. An unknown artist drew each race from life using a participating man or woman from the Midway dressed in clothing representative of their culture.[47]

The Midway was geared toward the middle class as well as those working-class people who could afford to go. Newspapers projected the belief that upper-class residents of the U.S. visiting the fair would not to want to spend time at the Midway because of its purported character as a tawdry spectacle. When an upper-class white person did go to the Midway, it was grounds for special mention in the newspapers, such as when the Spanish Infanta Eulalia visited without military escort.[48]

Food on the Midway was diverse and intentionally novel, from Boston baked beans to cold French cider.[49] In general, the fair expected to serve 356,400 meals per day and claimed “every style and variety of service for the cosmopolitan,” including the Midway, which was flooded with food services no matter the nature of the exhibit.[50] The fair at large exhibited regional foods from all over the United States, with individual state buildings that often featured some kind of concession. Some concessions even had a temporal aspect, such as the Old New England Cabin exhibit, where they served foods thought to be popular in the previous century.[51] Foreign delegations were less individualistic in their selections, offering at their concessions a few choice dishes they felt would be popular while representing a stereotyped aspect of their nation.

Prior to the 1870s, foreign foods were considered inferior and indigestible by U.S. middle- and upper-class whites. Anglo-Americans believed that palates were inherited according to one’s cultural background and status.[52] Lingering nationalist ideologies from the Civil War also discouraged the consumption of non-American foods during Reconstruction.[53] These ideas stemmed from the racial hierarchy constantly in play during the nineteenth century, in which peoples perceived as foreign were considered less civilized than white middle-class residents of the U.S. After Reconstruction, more and more people began living in urban areas, where they were more likely to both come into contact with individuals from other parts of the world and purchase food instead of growing their own.[54] Cosmopolitanism was not a result of new ways of thinking about ethnicity, but rather, a renegotiation of whiteness in urban environments in which a wide knowledge of the world reinforced superior status.[55] Also, most foreign cuisines were relatively inexpensive and allowed middle-class families to eat out cheaply on a regular basis.[56] Historian Yong Chen concludes that Chinese food in the U.S. during this period was viewed more as a kind of social service than a cuisine due to the inexpensive nature of the popular dishes.[57]

The same day as an article entitled “Food at the Fair” was printed, the Tribune also ran an article interviewing Dr. Gee Woo Chan about Luck Low, the head chef for the Chinese Café on the Midway, a pairing of Dr. Chan’s enthusiasm with an appeal to growing cosmopolitan taste among the white middle class.[58] The vast majority of food served at the fair, however, was Anglo-American fare—roasts, bread, sandwiches, ham, ice creams, coffee, and so on. Demand was so high that caterers were serving dishes that could easily be supplied in bulk.[59] In addition to regular fare, the Columbian Exposition also occasionally held special events, such as the International Ball, in which different cultures were expected to mingle. The food supposedly served at the International Ball was a bizarre combination of boiled potatoes, hash of unknown origin and ingredients, camel humps, monkey stew, reindeer, fried snowballs, doughnuts, and assorted sandwiches.[60] Such a spectacular advertisement would appeal to attendees that considered themselves cosmopolitan. Indeed, one article about the International Ball opened with a quote from a self-labeled cosmopolitan attendee that stated, “all men are brothers.”[61] An earlier Tribune article billed the Midway as the “Real Cosmopolis of the Great Exhibition,” enhancing its appeal as a cosmopolitan destination. The Midway had effectively domesticated the exotic for safe consumption by the white middle class.[62] The popular Rand McNally Columbian Exposition guidebook said that fairgoers should only visit the Midway after the White City, suggesting the higher importance placed on white “American” civilization.[63] The popularity of the Midway is perhaps best reflected in the looting that took place after the fair closed. By January the following year, little was left of the exhibit buildings as people took souvenirs of the “Merry Midway.”[64] By itself, the Midway paid out over four million dollars to the fair treasury, with an unknown amount of profit for the vendors.[65]

The Chinese Village

In protest against the 1882 and 1892 immigration acts, the Qing government, headed by Empress Dowager Cixi, refused to participate in the World’s Columbian Exposition. Despite the boycott by the Chinese government, Chicago Chinese still wanted to participate in the fair. They believed declining the offer had also lost China an opportunity to correct the unsavory stereotypes Westerners had attached to their culture. Presenting a respectable image of Chinese people to combat prejudices was the primary motive of the three prominent businessmen—Dr. Gee Woo Chan, Sling Hong, and Wong Kee—that organized the Chinese exhibit under the name Wah Mee (“Chinese American”) Corporation (see Figure 1).[66]

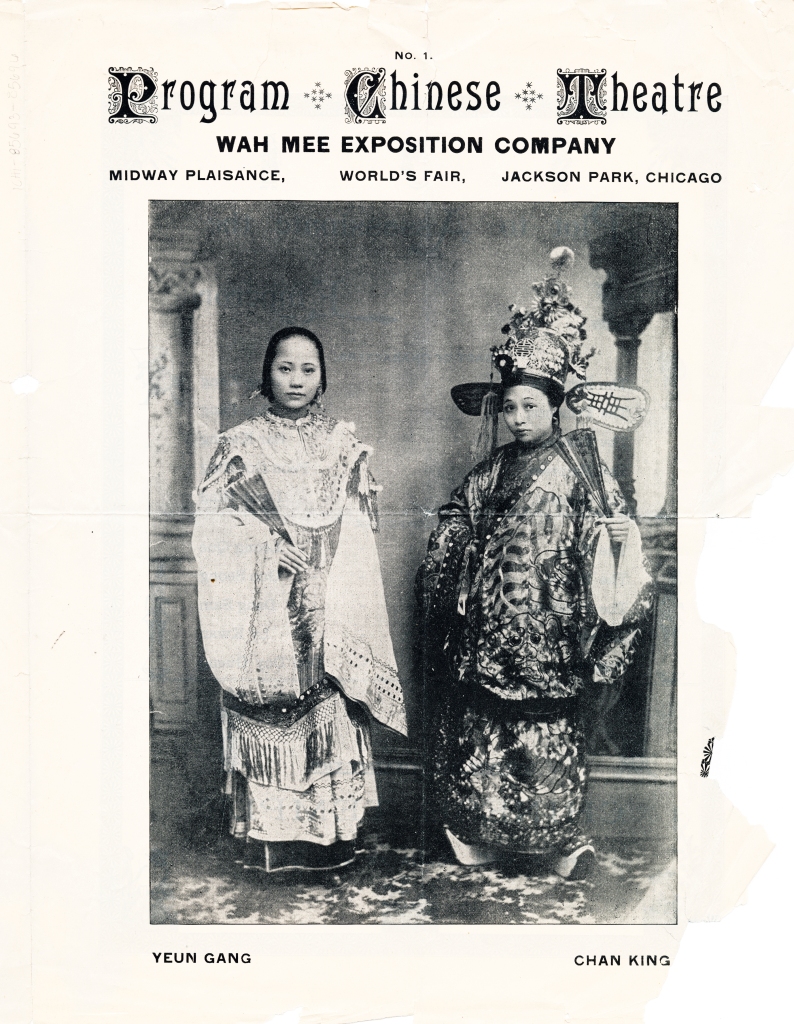

Chan was originally a Qing government official, but he also practiced herbal medicine. Upon arriving in the United States in 1884 to attend the New Orleans Exposition, he decided to invest in U.S. real estate and other business enterprises. Hong arrived in Chicago from Omaha, Nebraska, where he had invested in railroad real estate after a stint as a railroad contractor on the West Coast. He became a wealthy and experienced restaurateur connected with civic leaders in Chicago and believed the fair would be a good business opportunity. Wong was the owner of a Clark Street grocery and widely believed to be the richest Chinese man in Chicago.[67] All these men were praised by the newspapers for their business savvy and westernized lifestyles.[68] Chan was named president of the company and Hong general manager (see Figure 2), but Wong’s position is unknown. Wah Mee had competition from another merchant group with business objectives, the Wah Yung Company organized by the prominent Moy brothers, Dong Chow Moy and Dong Hoy Moy. Wah Mee ultimately won the spot on the Midway with a bid of $90,000 after the Moys were unable to move their theater troupe of four hundred past Immigration and Naturalization Services due to falsified permits.[69]

Although contradictory to the Chinese government’s decision, the men of the Wah Mee Co. felt that a Chinese presence at the fair would also help immigrants be seen as good residents of the U.S.[70] Without government support, they were only able to hire a Euro-American architectural firm (Wilson & Marble) to design the exhibit, as no Chinese firms would support the project.[71] Called the Chinese Village, the exhibit was located on the Midway Plaisance (see Figure 1) and boasted a theater, a “joss house” (catch-all English slang for a Chinese religious structure), bazaar, tea garden, and café. The Wah Mee Co. hired two hundred people from China to work at the exhibit. Goods, furnishings, and décor of all types were ordered to flesh out their plan for the Chinese Village experience. The Wah Mee Co. wished to give these features of the exhibit a respectable and traditional feel. Participation in the fair, they felt, was patriotic, but they also decided to participate in related activities to bolster their image. Hong, for example, marched at the head of his theater troupe as they carried the flags of the United States and China in the Independence Day parade held at the fair along with many other “grotesque” foreigners from the Midway.[72] The Chinese Theater also planned to put on a special performance of the story of U.S. independence in Chinese, according to the Tribune.[73]

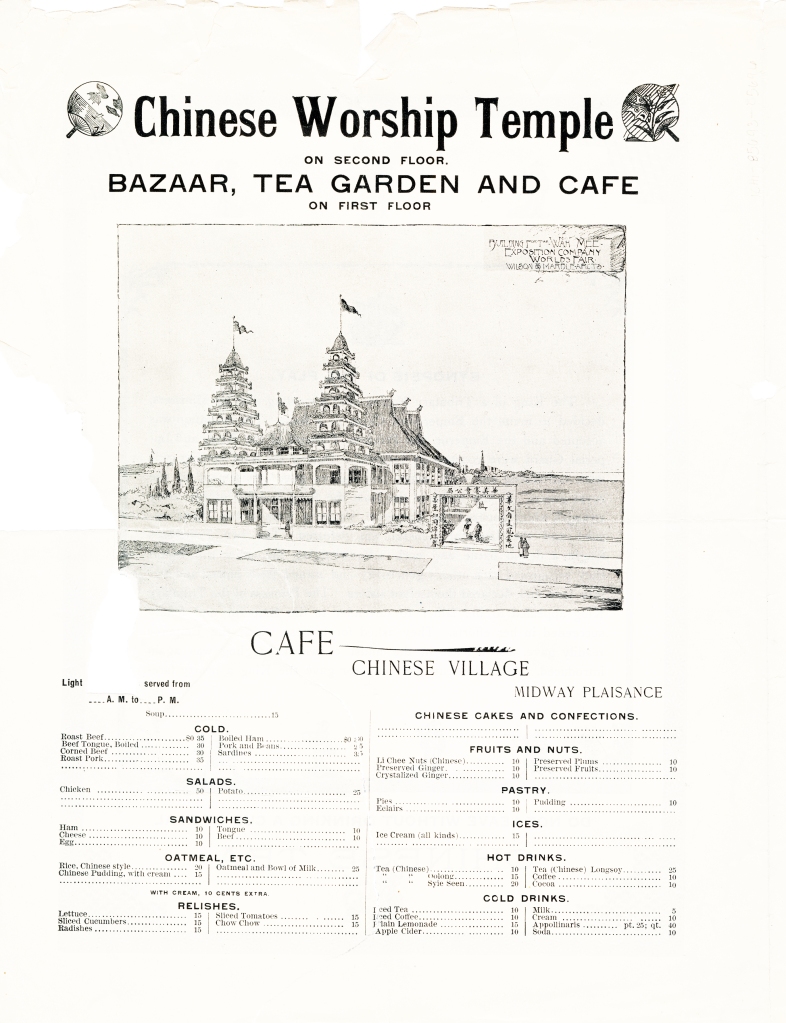

The image of Chinese culture presented at the fair was distorted, despite the best intentions of the Wah Mee Corporation. The architects were not familiar with Chinese style and created their own image of how the structure should look, which was more Thai than Chinese (a drawing of the exhibit can be seen in Figure 4).[74] The interior of the temple and theater complex, however, appeared to have been designed by someone familiar with Chinese style, contrary to the opinion of a newspaper reporter from the Tribune on September 24, 1893.[75] The shows at the theater were also classic stories, costumes, and roles, performed in Chinese by experienced actors from China.[76]

Placement of the Chinese Village on the Midway spoke to U.S. views of race, foreignness, and Chinese civilization. The Midway represented an asymmetrical relationship between the fair’s organizers and average fairgoers, the majority of whom were white residents of the U.S., and the various cultural groups represented. Considering the Midway spatially, the closest exhibits to the White City were the New England log cabin, Irish exhibits, Japanese bazaar (no relationship to the national Japanese exhibit located in the White City), and Hagenbeck’s animal show.[77] The Chinese Village was undeniably located near the very end of the Midway where it emptied out into the Wild East Show, an exhibit of Bedouin horsemen. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, an attraction that was unsanctioned by the fair’s management, lay just a few blocks south of the Midway at 63rd Street. The size of the Chinese Village was also considerably smaller than many of the other exhibits on the Midway. Old Vienna directly across the way appears to be at least three times the size of the Chinese Village on maps of the fair. Exhibits directly surrounding the Chinese Village included the Ostrich Farm, the Captive Balloon, the Brazilian Music Hall, the Combination Booth, Volcano Panorama, Old Vienna/Austrian Village, Dahomey Village, Lapland Village, and the Orpheum.[78] Reviews of the fair described none of these exhibits as particularly educational or civilized, which influenced the fairgoers’ perception of the Chinese Village. The use of the word village to describe the Chinese exhibit and many other exhibits on the Midway is significant. Close to but outside the White City, these false villages appear as subordinate to the “great white civilization.” Although China was an imperial power at the time, on the hierarchy of civilization portrayed by the organizers of the fair, it hardly deserved a spot on the map, unlike Japan, which received a prime location on Olmsted’s Wooded Island. Japan escaped criticism directed at other Asian nations at the fair by exhibiting qualities considered progressive, civilized, and “American.” White residents of the U.S. held a favorable yet paternalistic view of the Japanese government’s keen interest in commercial ties with the United States, as well as accelerating industrialization within Japan.[79]

Placed by journalists and the Wah Mee Co. alike, the Chinese Village was advertised in newspapers, fair catalogues, pamphlets, and guidebooks. The tone of the advertisements ranged from enthusiastic to morbid, depending on the writer. The men of the Wah Mee Co. worked hard to garner excitement from potential fairgoers for the exhibit. In a February 18, 1893 article in the Tribune, Chan was interviewed about the Chinese Café and teahouse to be opened in the Chinese Village. He expressed high hopes that the exhibit would garner the most curiosity from fairgoers, predicting that his acquisition of the “best cook in Hong Kong” would be a major draw.[80]

When the fair was in full swing, the Tribune published a sensational article entitled “Freaks of Chinese Fancy” complete with Chinese-inspired drawings.[81] A Tribune author described the exhibit as a cacophony of sound and activity, located near a boiler factory and railway station, with a band playing instruments of “barbaric construction” and participant names that were “unpronounceable for Christians.”[82] The band was reportedly comprised of a thief, a murderer, and a grave robber. Either the author was unaware of the true origins of the foods mentioned, or they were making a great show of sarcasm by calling ham sandwiches, corned beef, potato salad, and oatmeal with milk “characteristic Chinese delicacies.”[83] The author did, however, go on to recommend the Chinese method of fortune telling and describe the fortuneteller at the Chinese village as a professor in exotic clothing that was only capable of telling good fortunes, all of which appealed to the fantasies of fairgoers.[84] This author also gave the theater a more favorable review, though one steeped in Orientalist wonder. The piece ends with a criticism of the Chinese government for not participating in the fair when the Chinese attractions were clearly so popular.[85] The tone and content of this article contrasts with the informed and enthusiastic nature of Chan’s interview in the February 18th Tribune article.

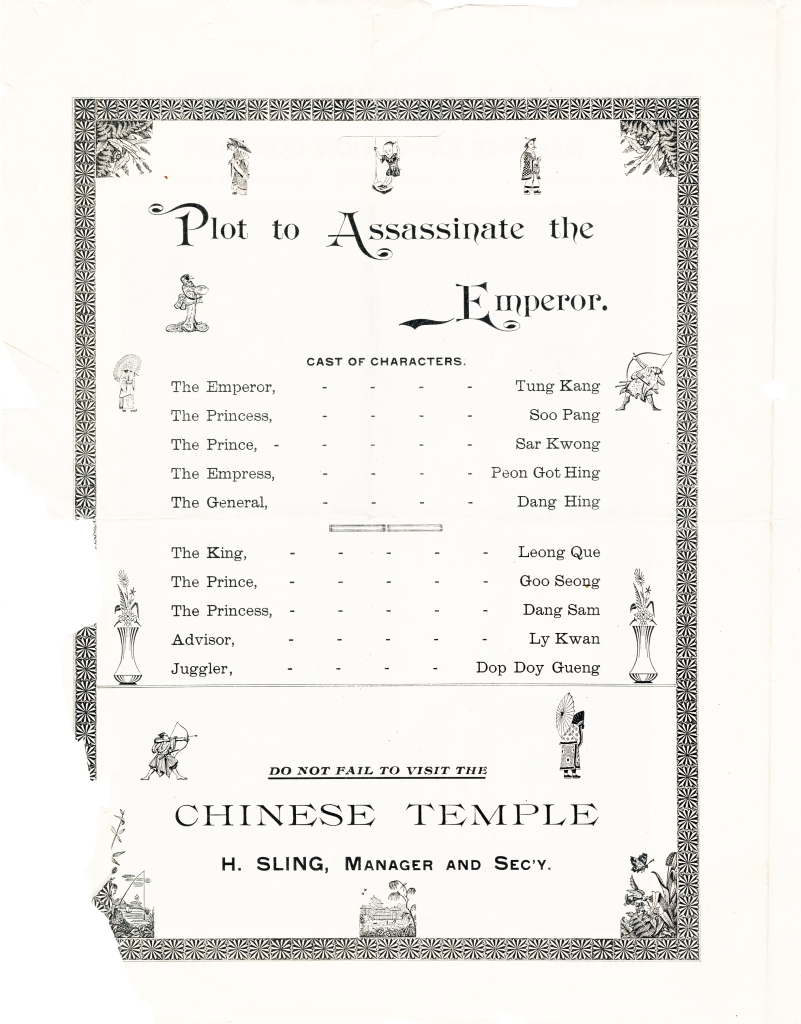

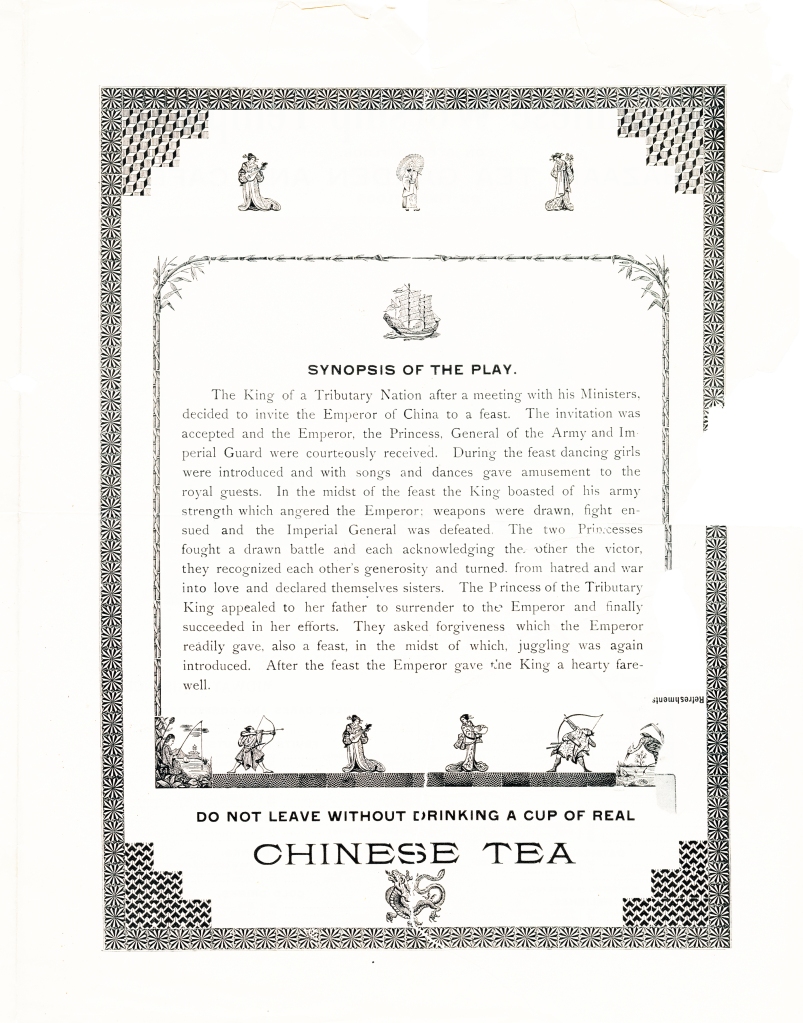

The exhibit pamphlet, organized for distribution by the Wah Mee Co., advertises authenticity to fairgoers and includes a stunning photograph of actors in costume and small but detailed motifs throughout. Under the synopsis of the play, the Wah Mee Co. entreats visitors in bold letters to “not leave without drinking a cup of real CHINESE TEA” (see Figure 2).[86] Of course, authenticity is a concept dependent on temporal and regional context as well as individual experience, and the men of the Wah Mee Co. exploited it to draw visitors to the exhibit. Cohesive authentic cuisine cannot exist because within a group there are varying opinions on what should and should not be included, which is further complicated by the shifting perspectives on the history of old dishes and the creation of new dishes.[87] The primary goal of most booths was to present an air of authenticity while feeding as many people as possible in a cheap and efficient manner. Therefore, authenticity in the context of the contact zone could be described as a performance for outsiders.[88] By advertising to serve “real Chinese tea,” backed up by Chan’s interview in the Tribune, the Wah Mee Co. made the exhibit appealing to culinary adventurers, while at the same time serving U.S. dishes to appear safe for the average fairgoer.[89]

The Chinese Café was approximately eighty by one hundred feet and was elaborately furnished with “ebony tables and stools all artistically inlaid with pearl.”[90] While no definitive record exists, the Chinese Café is widely believed by scholars of Chinese American history to be the first Americanized Chinese restaurant in the Midwest.[91] Although Chinese food encompasses myriad regional cuisines, each with unique characteristics, the Chinese Café exhibited not only an Americanized version but a homogenized version through its limited menu. The menu was not extensive and featured mostly U.S. and familiar European dishes, such as pork and beans, oatmeal, ice cream, and soda. The Chinese character of the café was found in the emphasis on rice, preserved fruits and relishes, and teas. Imported teas were valued at up to $100 per pound.[92] Some dishes were European in background, such as corned beef and éclairs, or of U.S. origin, such as sliced tomatoes. Other dishes were of uncertain background, or perhaps new inventions since the menu offered no description, such as “Chinese pudding, with cream.” Unfortunately, some sections of the menu are unspecific, namely the types of soups and “Chinese cakes and confections” that were available. Prices for food items ranged from five to fifty cents (see Figure 4). Foods advertised before the opening of the Chinese Village, such as yon wo gong and chow of jun, were not listed on the café menu.[93]

The Wah Mee Co. may have decided the café should primarily serve food that was not Chinese to appeal to a wider audience. The Midway was perceived to be a safe environment for white middle-class residents of the U.S. to enact fantasies of consumption in the form of exotic food, along with performances, souvenirs, and architecture.[94] Western utensils were provided, despite the fact that two thousand ivory chopsticks had been ordered for the exhibit. Chan was also quoted in the Tribune as having said, “English people can’t eat with chopsticks,” a statement suggesting that he felt fairgoers were not interested in a fully Chinese dining experience.[95] Middle-class culinary adventurers, like the traveling adventurers of Pratt’s Imperial Eyes, used the exotic as a way to negotiate their own identities through cultural contrast and appropriation.[96] Burgeoning culinary adventurism in the late nineteenth century was tempered by the culinary conservatism of the previous decades, and different cuisines became acceptable at differing rates.[97] White middle-class advocates of the melting pot approach to Americanization had stated goals of cultural homogenization and culinary uniformity, of which the Wah Mee Co. was surely aware.[98] Asian American studies scholar Robert Ji-Song Ku situates this process in the specific context of Chinese food, concluding that consuming the cuisine was not the same as accepting Chinese people and culture into U.S. society.[99]

The Chinese Café menu demonstrates that “foreign” at the 1893 fair was a concept defined by the contact zone. Chinatowns in the nineteenth century were stereotyped as being dirty and unsafe for the white middle class, although curiosity about foreign cuisines and their relative cheapness was beginning to push the boundaries of edibility in the middle class. White residents of the U.S. began to explore groceries and restaurants owned and operated by other cultural groups for ingredients and taste experiences.[100] The Chinese Village did not escape all of the criticisms Chinatowns in the United States received, but even the more sensational reports agreed that it was an attraction worth seeing.

The Wah Mee Co. chose to meet these white middle-class fairgoers on their own terms by offering safe foods like ham sandwiches and ice cream while offering a version of their culture partially based on Western expectations in the design of and activities within the Chinese Village. They also appealed to blossoming culinary adventurism by providing side dishes and teas that they felt were just exotic enough to be enticing. In this way, they were able to regain some control of their social image while exploiting the exotic fantasies of the fairgoers for profit.

While the Chinese Village was certainly the most popular and best advertised Chinese exhibit at the fair, it was not the sole representation of Chinese people. The Chun Quan Kee Company, also unsanctioned by the government of China, occupied three thousand square feet in the Manufactures Building to display industries, products, arts, and artifacts of China.[101] The relationship of the Chun Quan Kee Co. to the Wah Mee Co. is not known. The contradictory placement of Chinese industries in the White City while food was placed on the Midway illustrates the dual subordinate roles assigned to Chinese people as economic support for U.S. imperialism and as perpetual foreigners unworthy of acceptance into U.S. society.

Legacy of the Chicago World’s Fair

Before the fair ended, the Wah Mee Co. went bankrupt. Chan, Hong, and forty to fifty other investors in the Chinese Village exhibit were swindled out of at least $60,000 put up for its development by their own secretary and treasurer, Pak Kuae Chan and Ming Sue Chan. The latter was put in jail, and Wing Sue Chan, one of the agents sent to purchase exhibit goods in China, was eventually retrieved by a Chinese American detective and found in violation of the Exclusion Act for providing passage for two hundred and eighty “actors” not requested by the Wah Mee Co. Over a year after the China expedition began, the investors discovered that only about half of the goods they received for the exhibit had been paid for, and many others were charged double with profits pocketed by Pak Kuae Chan, who refused to return to the United States on the pretense of illness.[102] After the fair ended, an unknown number of migrant workers were unable to return home.

In addition to Chinese Chicagoans, many other Chinese immigrants moved to Chicago after the Columbian Exposition was announced, some to visit the fair, but most were looking for employment. Pak Kuae Chan used his status to attempt to lead four hundred and eighty hopeful immigrants into the United States. Approximately five hundred more were reported to have been traveling with them in an attempt to get into the country.[103] These immigrants paid a fee to be included on the ship with Ming Sue Chan, but most were turned away by Gee Woo Chan, who selected the two hundred requested by the Wah Mee Co. before sending the remaining hundreds back to China.[104] Many more, however, were able to get through, and Chinese immigrants already in the U.S. migrated to Chicago. The main jobs available for them in Chicago were in restaurants and laundries, as in the rest of the country, but they also opened new businesses such gift shops and grocery stores.[105]

At the turn of the twentieth century, Chinese restaurateurs were beginning to define a trend of fine Chinese dining in Chicago. While some distinctions in regional cuisines began to appear among new restaurants, these establishments often catered to U.S. ideas of Chinese food.[106] After arriving in Chicago in 1895, F. Foin Chin owned the first truly luxurious—but thoroughly westernized—Chinese restaurant in the city by 1905. The crown jewel of Chicago Chinese restaurants was arguably Chin’s King Joy Lo, where high Mandarin fare was served alongside first-class U.S. cuisine and reservations were always required.[107] The Guey Sam Restaurant (owner unknown), also considered upscale, opened in 1901. Other notables were Wee Ying Lo and Song Ying Lo restaurants, owned by the Moy brothers and opened in 1903. All of these were located in or near the Clark Street Chinatown, had substantial seating, and were extravagantly designed. Chinese residents patronized these Chinatown restaurants, which served dishes that would have been familiar to their customers. Outside of Chinatown, however, fine Chinese restaurants catered to a more diverse crowd.[108] Chinese restaurants in Chicago became so lucrative that laundrymen invested in them to turn a larger profit than they received from the laundry business.[109] Chicago quickly became the self-proclaimed center of Chinese fine dining in the early years of the twentieth century.[110]

Unlike these fine-dining establishments, the ordinary Chinese restaurants that spread around Chicago were mostly chop suey houses. The dishes served at these types of restaurants were considered Americanized because they generally utilized local ingredients and tools. Their décor was far less luxurious than the upscale restaurants centered around Clark Street and the few located in other neighborhoods. The Tribune attributed the rise in the number of Chinese restaurants to the fair, because they increased exponentially with the boom in the Chinese population in 1893. Around the city, property rental agents initially refused Chinese restaurants because they felt these establishments would draw unwelcome clientele, but a member of the Moy family—Sam Moy—worked with them on behalf of restaurant companies to change public opinion. Chinese restaurateurs hoped to draw customers away from German and French establishments by providing a more adventurous choice cultivated by the fair. Most boasted at least one head chef that had been trained in China. According to the Tribune, popular dishes, besides chop suey, included mandarin punch, yang hammer, and spicy Spanish stew, all newly invented for U.S. palates. Meals usually cost about twenty-five cents, an appealing price for the restaurant-going middle class.[111] Although rising in popularity, chop suey and other Chinese American or Chinese dishes were still considered mysterious because of their foreign sounding names and cooking methods unfamiliar to residents of the U.S.[112] By the early twentieth century, Chicago had become a booming industry in supplies for bird’s nest soup, an expensive Chinese soup made with swifts’ nests.[113] Guides regarding what to order in Chinese restaurants began appearing in newspapers. These articles assured restaurant-goers that Chinese dishes were delicious, safe, and affordable.[114] Ideals of authenticity were tied up with what Ku defines as a “daring, adventurous, and daunting” approach to Chinese food for white enthusiasts.[115]

The simultaneous rise of fine and common Chinese restaurants in Chicago spawned elitism in U.S. consumers of Chinese food. Diners who wanted to be seen as having more discerning tastes were attracted to large, extravagantly decorated restaurants where the food was purportedly more authentic than the refined taste experiences found in China.[116] Part of the draw for these restaurant-goers was the lavish décor of fine establishments, pictures of which often took up more page space than the associated newspaper article. According to historian Rebecca Spang, the turn of the twentieth-century restaurant was a place of “daydream and fantasy,” where patrons imagined their own identities as global adventurers.[117] Such imagery printed in the newspapers fueled the foreign food fantasies of potential customers and appealed to their desire to appear rich and worldly to their peers, performed through consumption.[118] Like the Chinese Village, the atmosphere and menus of these restaurants were carefully cultivated to appeal to middle-class U.S. culinary adventurism, whether they claimed authenticity or the safety of U.S. dishes. Despite the efforts of restaurant owners, Chinese food as a fine dining experience never became as popular as the inexpensive dishes, in part because white middle-class residents of the U.S. maintained belief in their racial superiority by refusing to view Chinese Americans as anything but uncivilized and foreign.[119] In this way, the contact zone which began on the Midway widened to include the rest of the city as the popularity of Chinese food exploded over the next fifteen years. Chinese restaurateurs helped to push the boundaries of edibility in Chicago by recognizing the demand for foreign foods after the fair and opening restaurants which offered dishes that would be considered more exotic than those found at the Chinese Village.

Conclusion

Through the foods carefully chosen for the menu, the Chinese Village on the Midway Plaisance at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 created a contact zone where white middle-class residents of the U.S. believed they could safely enact their exotic fantasies and culinary adventurism. Chinese Americans participating in the fair were not, however, a static cultural group, but rather, savvy businessmen who exploited exoticism and culinary adventurism to turn a profit by presenting an image that was respectable for them yet also expected by the fairgoers. The Wah Mee Co. was not successful financially because of embezzlement within the corporation, but it did help to pique cosmopolitan interest in Chinese food, which made subsequent Chinese restaurants popular with middle-class Chicagoans after the fair closed.

The Chinese population boom in Chicago that resulted from the fair was also a major contributing factor to the spread of Chinese restaurants around the city. These men were able to create successful restaurant businesses catering to a new wave of restaurant-goers. Culinary adventurism among middle-class residents of Chicago was a continuation and broadening of the contact zone begun on the Midway. Foreign foods were quickly stretching the boundaries of edibility for middle-class residents of the U.S. because these cuisines were mostly inexpensive and fit with ideas of racial superiority and worldliness. Within fifteen years of the close of the fair, culinary adventurism spawned culinary elitism, or the perception of having cultivated taste for authenticity, among white patrons of Chinese restaurants. White middle-class consumers considered chop suey houses less authentic compared to the new luxury Mandarin restaurants that wealthy Chinese American businessmen were opening around the city, although fine dining establishments never achieved the same level of popularity as inexpensive Chinese restaurants. Owners of luxury restaurants outside of Chicago’s Chinatown recognized this culinary elitism and continued to cater to white middle-class exotic fantasies, offering the finest in non-Chinese and Chinese cuisine.

Notes

[1] “From Other Lands. Exhibits That Make the Fair International in Scope. Results of Hard Work. How the Attention of the Various Countries was Secured. Only One Unrepresented,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 30, 1894, 33.

[2] Raymond D. Fogelson, “The Red Man in the White City,” in The Spanish Borderlands in Pan-American Perspective, ed. David Thomas Hurst (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 75.

[3] Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (New York: Routledge, 1992), 4–6.

[4] Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United State Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876–1917 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 4.

[5] Arjun Appadurai, “How to Make a National Cuisine: Cookbooks in Contemporary India,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 30, no. 1 (1988): 3–24.

[6] Pratt, Imperial Eyes, 7.

[7] Yong Chen, Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America (New York: Columbia University Press), 130–133; Heather R. Lee, “A Life Cooking for Others: The Work and Migration Experiences of a Chinese Restaurant Worker in New York City, 1920–1946,” in Eating Asian America: A Food Studies Reader, eds. Robert Ji-Song Ku, Martin F. Manalansan IV, and Anita Mannur (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 55–56.

[8] Chen, Chop Suey; Anne Mendelson, Chow Chop Suey: Food and the Chinese American Journey (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 30–32. Mendelson notes that these methods were largely unknown among residents of the U.S. before Chinese immigrants began arriving in large numbers in the second half of the nineteenth century.

[9] Ibid.

[10] See, for example, the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864) and the Boxer Uprising (1898–1900). Exhibit text, Great Wall to Great Lakes: Chinese Immigration to the Midwest, Chinese American Museum of Chicago (CAMOC), Chicago, IL. Overburdened and insufficient farmland as a result of population increases in some regions of southern China during the period from 1838 to 1920 led to local food shortages; Mendelson, Chow Chop Suey, 56–57.

[11] Benson Tong, The Chinese Americans, Revised Edition (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2003).

[12] Mae M. Ngai, “Chinese Gold Miners and the ‘Chinese Question’ in Nineteenth-Century California and Victoria,” Journal of American History 101, no. 4 (2015): 1093.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Chuimei Ho and Soo Lon Moy, ed., Images of America: Chinese in Chicago, 1870–1945 (Chicago: Arcadia, 2005), 8.

[15] Tong, The Chinese Americans.

[16] Yuki Ooi, “‘China’ on Display at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893: Faces of Modernization in the Contact Zone,” in From Early Tang Court Debates to China’s Peaceful Rise, eds. Friederike Assandri and Dora Martins (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009), 60; Dr. Sun Yat-sen, revolutionary and world traveling Guangdong native, was instrumental in popularizing the Chinese nationalist political movement at this time. Later, he would come to be called the “father of the nation” and hold office as president of the provisional government.

[17] Paul C.P. Siu, The Chinese Laundryman: A Study of Social Isolation (New York: New York University Press, 1987), 296–97.

[18] Ronald Takaki, Iron Cages: Race and Culture in 19th-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 216–217.

[19] Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 76.

[20] Chen, Chop Suey, 82–85, 97–99; Robert Ji-Song Ku, Dubious Gastronomy: The Cultural Politics of Eating Asian in the USA (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2014), 54; Takaki, Iron Cages, 217–220; Tong, The Chinese Americans; J.S. Tow, The Real Chinese in America (New York: The Academy Press, 1923).

[21] Great Wall to Great Lakes: Chinese Immigration to the Midwest, Chinese American Museum of Chicago (CAMOC).

[22] Ooi, “‘China’ on Display at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893,” 57–58.

[23] Ho and Moy, Chinese in Chicago, 8.

[24] This information is based on the experiences and research of Eugene Kung, CAMOC volunteer researcher. I conducted a personal interview with Mr. Kung and his wife, Ruth, in 2007. Mr. Kung’s study guide was on display at the CAMOC during the Paper Sons exhibition, held May 21–December 1, 2005, and is currently displayed in the Great Wall to Great Lakes permanent exhibition.

[25] “Evaded the Law,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 7, 1894, 7. Precursors to the United States Border Patrol were not active until 1904.

[26] Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 13.

[27] Ibid., 14–26.

[28] Ibid., 50.

[29] Takaki, Iron Cages, 247–248.

[30] Ho and Moy, Chinese in Chicago, 9.

[31] Huping Ling, “Chinese Chicago: Transnational Migration and Businesses, 1870s–1930s,” Journal of Chinese Overseas 6 (2010): 254.

[32] “Chinese Pay to Join the Players. Testimony that Will Be Offered Against Ching Ming Sue,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 19, 1894, 8.

[33] Great Wall to Great Lakes: Chinese Immigration to the Midwest, Chinese American Museum of Chicago (CAMOC).

[34] Ooi, “‘China’ on Display at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893,” 59.

[35] Pascal Blanchard, Nicolas Bancel, Gilles Boëtsch, Eric Deroo, and Sandrine Lemaire, “Human Zoos: The Greatest Exotic Shows in the West,” in Human Zoos: Science and Spectacle in the Age of Colonial Empires, eds. Blanchard et al. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008), 1–49. The term “human zoo” was derived by the authors from Carl Hagenbeck’s historical term “anthropozoological exhibition.” Hagenbeck held a display of exotic and dangerous animals at the Chicago fair but did not have a hand in the ethnographic displays of the Midway. Native groups from around the world were approached by recruiters like Hagenbeck and offered monetary incentive or popular goods in exchange for volunteers. While the people involved did consent to the arrangement, they were not well informed about the conditions in which they would be forced to live in order to receive compensation. Some groups were recruited and given autonomy over their own displays, and some enterprising individuals chose to rent their own space and capitalize on their Otherness. Persons with abnormal physical features or abilities were also popular for human zoo exhibits. The common theme that categorizes all of these as human zoo exhibits is the exploitation of race or abnormality as entertainment.

[36] Reid Badger, The Great American Fair: The World’s Columbian Exposition and American Culture (Chicago: Nelson Hall, 1979), 107.

[37] Ibid., 80; Robert W. Rydell, “The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893: Racist Underpinnings of a Utopian Artifact,” Journal of American Culture 1, no. 2: 253–275.

[38] Badger, The Great American Fair, 81; Rebecca S. Graff, “Being Toured While Digging Tourism: Excavating the Familiar at Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 15 (2011): 222.

[39] Fogelson, “The Red Man in the White City,” 86.

[40] Ibid., 75–77; Graff, “Being Toured While Digging Tourism,” 226–227; Ooi, “‘China’ on Display at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893,” 62–63; Rydell, “The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893,” 269–270.

[41] Robert W. Rydell, http://encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1386.html, 2005.

[42] A few opinions from non-white participants were recorded, such as Chief Solomon O’Bail of the Seneca, who said he “had good time all summer” (quoted in Fogelson 86). When one considers that these records were preserved in newspapers or reports of the fair, they are nearly impossible to verify. Many participating groups suffered from heat, disease, and inhumane living conditions or were stranded after the fair ended. Therefore, it seems likely that Midway participants were aware of their low social status in the United States, if not their specific place in the white-dominated hierarchy.

[43] Badger, The Great American Fair, 81; Rydell, http://encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1386.html.

[44] “Wonderful Place for Fun: What the Money Catchers Offer in the Midway Plaisance,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 19, 1893, 9.

[45] Badger, The Great American Fair, 107; Cartographer unknown, Studebaker Map of World’s Columbian Fairgrounds, 1893 (Chicago Historical Society: ICHi-37111).

[46] Badger, The Great American Fair, 109.

[47] “Race Types at the World’s Fair Sketched from Life,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 30, 1893, 25. From photos of the Midway published in guidebooks during the fair and albums after the fair closed, the drawings were accurate portrayals of what participants wore to work, but the articles placed non-white individuals within a hierarchy of races.

[48] “She Enjoyed the Sights: The Spanish Princess Again at the Fair. All Semblance of Royalty Left Behind. She Rambled About the Grounds Like an Ordinary Mortal. Midway Plaisance and Other Areas of Interest Visited,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 10, 1893, 1.

[49] Justus D. Doenecke, “Myth, Machines, and Markets: The Columbian Exposition of 1893,” Journal of Popular Culture 6, no. 3 (1973): 537.

[50] “Low Luck Will Be Head Cook,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Feb. 18, 1893, 9.

[51] “Like a Kaleidoscope. Midway Plaisance Thronged with People of All Nations,” May 29, 1893, 2.

[52] Andrew Haley, Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 97.

[53] Kristin L. Hoganson, Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 106.

[54] Ibid., 112.

[55] Ibid., 105–151. Blanchard et al., “Human Zoos,” 1–49.

[56] Haley, Turning the Tables, 92–117.

[57] Chen, Chop Suey, 126.

[58] “Food at the Fair: Restaurant Arrangements; Their Extent and Capacity,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Feb. 18, 1893, 9. Chinese names are written here in the English style with the family name at the end. Inconsistencies in westernized Chinese names printed in nineteenth-century U.S. newspapers make it occasionally difficult to determine the correct name. I have tried to select the most commonly printed version for this essay.

[59] “Food Enough For All: But It Is a Task to Feed the Chicago Day Multitude,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Oct. 10, 1893, 9; The Wellington Catering Company alone, located in the White City, was said to use 40,000 pounds of meat; 12,000 loaves of bread; 200,000 ham sandwiches; 400,000 cups of coffee; 15,000 gallons of ice cream; two cartloads of potatoes; and 4,000 half barrels of beer in one day.

[60] “The International Ball at the Fair,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 17, 1893, 1; Whether or not some of these were actual dishes served or sensationalism promoted by the newspapers is unclear. I am inclined to believe the latter.

[61] Ibid.

[62] “Wonderful Place for Fun: What the Money Catchers Offer in the Midway Plaisance,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 19, 1893, 9; Doenecke, “Myth, Machines, and Markets,” 538.

[63] Rydell, “The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893,” 268.

[64] “Highway of Nations. Last Scene in the History of an Erstwhile Famous Street. Merry Midway, Adieu! Despoiled by Relic-Hunters Lies Dismantled. But All Its Best Features Are Happily Preserved in the Art Portfolios,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 15, 1894, 3.

[65] “Story of the Fair,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Nov. 1, 1893, 16.

[66] “Chinese Nipped in Midway Deal. Chan Ming Sue and Chan Pak Kuae Said to Have Embezzled $60,000,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 16, 1894, 12; Pak Kuae Chan and Ming Sue Chan, along with Gee Woo Chan, were originators of the exhibit, with Sling Hong and Kee Wong added later. Not much is known about the Pak Kuae Chan and Ming Sue Chan other than their positions of secretary and treasurer respectively of the Wah Mee Co. Several other prominent Chicago Chinese were involved in the exhibit, as well as a man from Kansas City, and a man from San Francisco, and forty or fifty other prominent Chinese in the United States.

[67] Ling, “Chinese Chicago,” 269–270; An actual summary of Wong’s assets is unavailable.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Ibid., 279. “Chinese Bound for Chicago: Customs Officers Believe that Many of Them Carry Bogus Certificates,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 17, 1893, 1.

[70] Ooi, “‘China’ on Display at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893,” 58–59.

[71] Ho and Moy, Chinese in Chicago, 110.

[72] “All Nations Join In. Unique Patriotic Celebration on the Midway Plaisance,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 5, 1893, 9, 11; “It was all patriotic and beautiful, but it was grotesque, nevertheless, to see half-naked Soudanese, long-gowned Arabs, Chinamen and Turks celebrating an event they did not understand, but as patriotic and loyal in their cheering for all that as the people who were born under the Stars and Stripes.” Hong was also given the title “Colonel” in this article as well as several others, but I was unable to authenticate their use.

[73] “Celebration on the Plaisance. The Nations of the Earth Will Do Honor to the Republic’s Birth,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 4, 1893, 2.

[74] Ho and Moy, Chinese in Chicago, 110–111.

[75] Ibid; The Tribune reporter wrote, “[T]he exhibitors have a different idea of a Joss House from that of their coreligionists, or else that they have sent their Joss away to be mended” (33). “Joss” was the term that white people used for any number of Chinese folk deities and indicated a poor understanding of Chinese belief systems. The article refers to the lack of a joss statue in the Chinese Village, where the Wah Mee Co. desired to portray a respectable and accurate image of Chinese culture.

[76] Ibid., 112.

[77] Cartographer unknown, Studebaker Map of World’s Columbian Fairgrounds, 1893 (Chicago Historical Society: ICHi-37111).

[78] Ibid.

[79] Rydell, “The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893,” 259–260.

[80] “Low Luck Will Be Head Cook,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Feb. 18, 1893, 10.

[81] “Freaks of Chinese Fancy,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Sept. 24, 1893, 33.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Ibid.

[86] Wah Mee Exposition Company, “Program Chinese Theater” (Chicago Historical Society: F38MZ 1893. Z Oversize 189978).

[87] Chen, Chop Suey, 127.

[88] Ku, Dubious Gastronomy, 37.

[89] “Low Luck Will Be Head Cook,” 10.

[90] Ibid.

[91] Ling, “Chinese Chicago,” 270.

[92] Trumbull White, The World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 (Boston: J.W. Ziegler, 1893), 580.

[93] “From Other Lands. Exhibits That Make the Fair International in Scope. Results of Hard Work. How the Attention of the Various Countries was Secured. Only One Unrepresented,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 30, 1983, 33.

[94] Blanchard et al., “Human Zoos,” 20; Hoganson, Consumers’ Imperium, 121–135.

[95] “Low Luck Will Be Head Cook,” 10.

[96] Haley, Turning the Tables, 97–98; Ibid., 137; Pratt, Imperial Eyes, 7.

[97] Haley, Turning the Tables, 98.

[98] Hoganson, Consumers’ Imperium, 210–211.

[99] Ku, Dubious Gastronomy, 52–53.

[100] Haley, Turning the Tables, 92–117.

[101] “From Other Lands,” 33.

[102] “Chinese Nipped in Midway Deal,” 12.

[103] “Chinese on the Way to Chicago. Many More Than Are Authorized Reported to Be Coming,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 16, 1893, 1; Deputy Collector McCarthy quoted in the Tribune: “If there are 1,000 Chinese on the way here, why, it must be a sort of desperate attempt to get Chinese into this country. It is a sort of last resort, I suppose, as the opportunity comes only with the Fair.”

[104] “Chinese Nipped in Midway Deal,” 12; “Chinese Pay to Join the Players,” 8.

[105] Chen, Chop Suey, 3–56; Ooi, “‘China’ on Display at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893,” 59.

[106] Chen, Chop Suey, 135–138.

[107] “King Joy Low, the Finest Chinese-American Restaurant in the World,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Dec. 22, 1906, 20.

[108] Ling, “Chinese Chicago,” 268.

[109] Ibid., 274.

[110] “King Joy Low,” 20.

[111] “Chinese Restaurants Increasing in Popularity,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 26, 1902, A7.

[112] “Chop Suey Fad Grows: Chicago’s Appetite Is Becoming Cultivated to Chinese Dish of Mystery,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 19, 1903, 43.

[113] “Chicago Headquarters for Edible Birds’ Nests,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 17, 1904, 68.

[114] “What to Order in a Chinese Restaurant,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 20, 1907, F3.

[115] Ku, Dubious Gastronomy, 66.

[116] “Joy Hing Lo,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 31, 1908, 18.

[117] Rebecca L. Spang, The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 235.

[118] Hoganson, Consumers’ Imperium, 121.

[119] Chen, Chop Suey, 86–134; Ku, Dubious Gastronomy, 60–61.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Kimberly Krause for excellent research assistance, Dr. Helen Veit for her comments and encouragement on early versions of this essay, and Eugene and Ruth Kung at the Chinese-American Museum of Chicago for sharing their personal experiences.

Biography

Grace Krause is a doctoral candidate in anthropology at Michigan State University, specializing in historical archaeology and foodways. For her dissertation, she is exploring the role of food in the business of commercial sex in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century New Orleans, utilizing zooarchaeology and landscape analysis. Alongside her research, Grace is a mentor for the Mid-Michigan Chapter of the Graduate Women in Science Undergraduate Mentoring Program.