Robotic fish designed to terrorize invasive species passes initial tests

Fear-dealing robots disguised as largemouth bass may be the key to solving a century-old quandary.

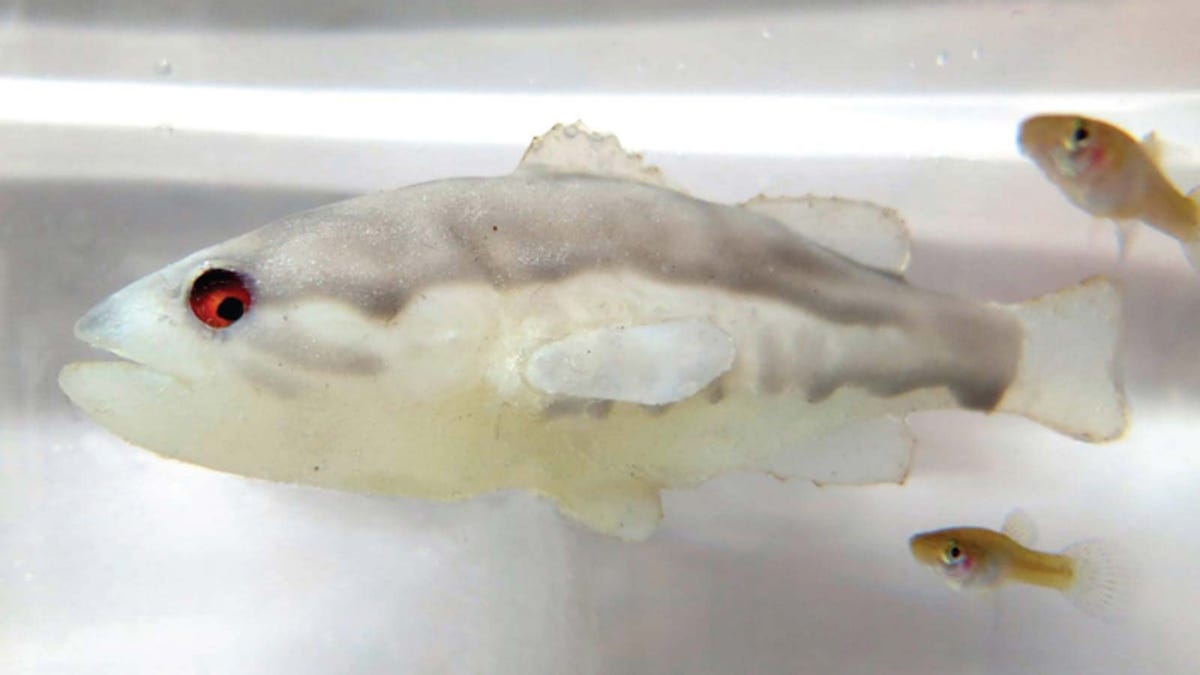

It may look like a fish...

A robot that looks and swims like a largemouth bass is effective at preventing mosquitofish from devouring vulnerable tadpoles, according to a study published Dec. 16 by iScience. Considering mosquitofish have become a global pest over the last 100 years, the robotic fish could be big news for ecosystems across the globe threatened by the invasive species.

How did the mosquitofish become such a problem for native species of fish across the world? Naturally, it's humans' fault.

In the early 1900s, mosquitos were a problem. The invention of modern mosquito repellent was still a half-century away, so a species called Gambusia affinis, known to prey on the larva of the pesky insects, was introduced in regions throughout the world as a mosquito-control agent. As you might expect, this is how the mosquitofish earned its name.

The problem is mosquitofish don't just eat mosquito larva. These tiny fish have hardy appetites for larva of all kinds, including tadpoles for rare and economically important species of fish and amphibians native to waterways where the mosquitofish was introduced. They've been an issue ever since, and now scientists may have come up with a solution.

Scientists built the robot to look and move like the natural predator of the mosquitofish: the largemouth bass. The robot uses "computer vision" to spot mosquitofish when they approach tadpoles, and then the robot moves in to scare the predators away.

"Invasive species are a huge problem worldwide and are the second cause for the loss of biodiversity," said the study's first author, Giovanni Polverino of the University of Western Australia. "Hopefully, our approach of using robotics to reveal the weaknesses of an incredibly successful pest will open the door to improve our biocontrol practices and combat invasive species."

To conduct the study, scientists set up tanks containing mosquitofish and tadpoles, then introduced the robot. They found the robot was effective in scaring off the mosquitofish. The anxiety that the robot created in the mosquitofish altered their behavior, physiology and fertility, essentially making them less effective at preying on the tadpoles over the five weeks of the study. The mosquitofish exposed to the robot became more focused on fleeing, rather than reproducing.

"While successful at thwarting mosquitofish, the lab-grown robotic fish is not ready to be released into the wild," said the study's senior author, Maurizio Porfiri of New York University.

So while the results of the study are promising, the team still has a few technical hurtles to overcome. But this novel approach to combating invasive marine life could be the beginning to the end of the world's mosquitofish headache.