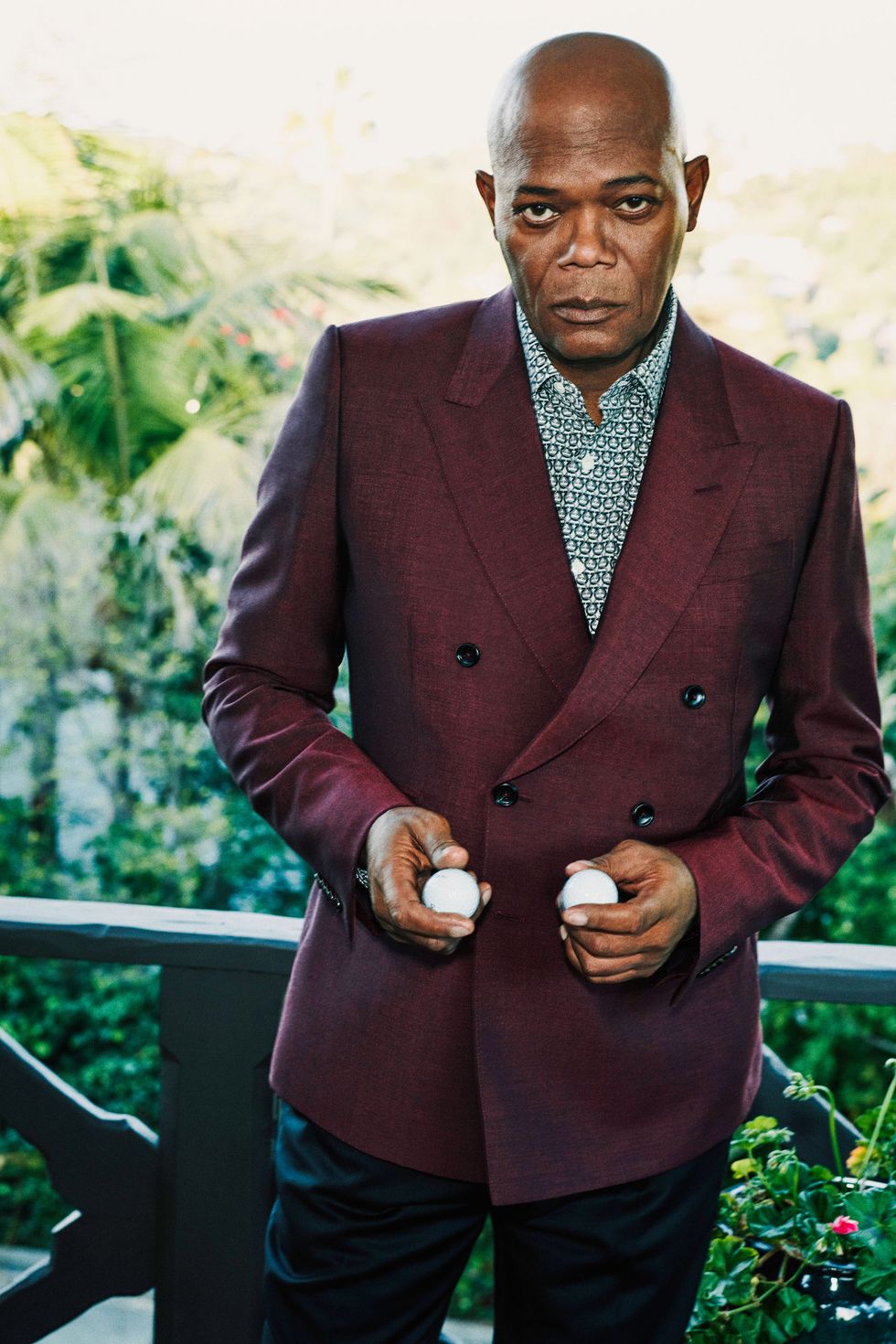

Samuel L. Jackson is driving our golf cart pedal to floor through the unseasonably cold southern California morning fog, pushing the whining electric engine to its limits. It is 8:15 a.m., and he and his foursome have already played nine holes. I met up with them at the turn and hopped into Jackson’s cart as they continued on the course, interrupting their mild shit-talking with sporadic occurrences of golf on the back nine. It is one of those bizarrely random Los Angeles groupings of people you never imagine together. Richard Schiff puffing on a cigarette in a faded Yankees cap and pink-trimmed performance golf slacks. An unfailingly upbeat producer-writer who spends much of the time encouraging everyone’s shots and explaining the game of cricket. A young semipro in a razor-crisp polo who drives the ball off the tee like he’s opening up a portal to another dimension. Don Cheadle is supposed to be here but is absent for unknown reasons. (We eventually discover on the clubhouse television that it has to do with him appearing on Good Morning America at that precise moment.) I later hear that Josh Duhamel frequently rounds out the group. I have never been on a golf course in my life.

Jackson drives, peppering me with questions (“Have white folks started confusing you with Brian Tyree Henry yet?”) and gleefully navigating around obstacles in our path by running two wheels up on the wet grass despite bountiful signage warning us not to do just that. Each time he does this, the cart threatens to pull a little movie-stunt two-wheel tip and throw me onto the asphalt pathway. “Engage your core,” he tells me with an 85 percent straight face. It is good advice from a seventy-year-old man from Chattanooga, Tennessee. I am vaguely scared and trying to play it cool. He is driving decisively, wholly unconcerned. At his age, the Hollywood veteran wears “wholly unconcerned” as comfortably as the faded black Adidas bucket hat he golfs in.

This becomes clear to me when I later interview him in the country-club restaurant and he sprinkles n-words and motherfuckers about the dining area like handfuls of glitter as Grandpa- and Memaw-type club members look awkwardly into their eggs Benedict. He behaves not only like a man who belongs here but also like one who basically owns the place. His casual inattention to the perceived authority of white power structures is so deeply woven into his way of being that in his presence it seems bizarre that anyone, anywhere, would think to behave differently. A lot of people like to say they don’t give a fuck. Samuel L. Jackson simply doesn’t.

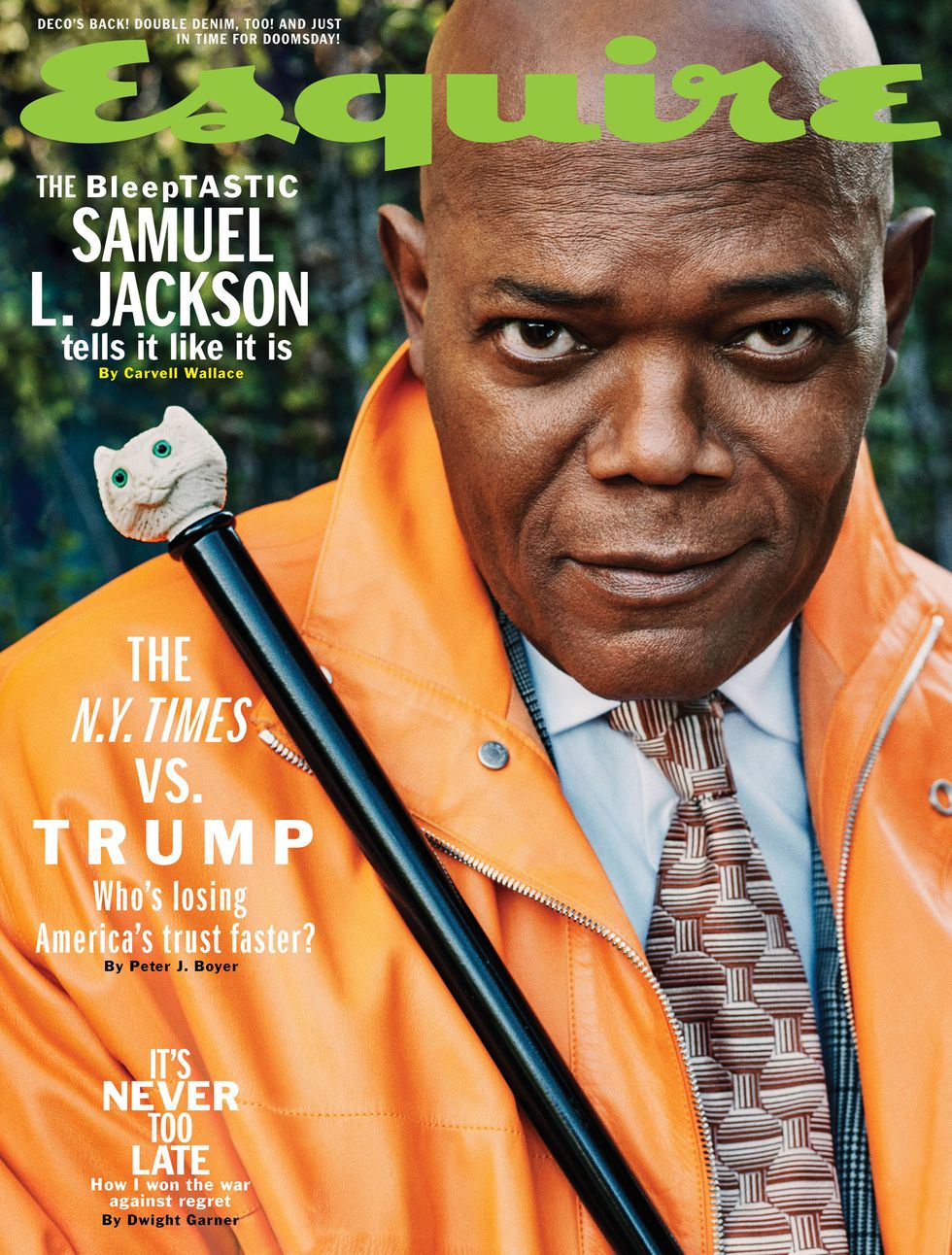

What he does care a great deal about is acting and movies (and golf—he is coy about his handicap but acknowledges it lies in low single digits), and he approaches his craft with both a childlike love for the medium and a specialist’s obsession with technique. This combination has led him to enjoy one of the most prolific film careers of any actor alive, despite his relatively late-in-life big break. Perhaps only Nicolas Cage comes close to achieving Jackson’s ability to pop up across a pantheon of wildly disparate titles, ranging from the sublime (Pulp Fiction, Unbreakable, Eve’s Bayou) to the absurd (Snakes on a Plane, Jumper, The Man). I had heard that he averaged four releases a year, which I thought was insane until he corrected me and told me that it was closer to five.

In two separate calendar years, 1990 and 2008, Samuel L. Jackson’s name was on the call sheet for seven different films. Moreover, he has found his way into megafranchises like Star Wars and The Incredibles, and as former SHIELD director Nick Fury, Jackson has shot eleven different Marvel movies, including four Avengers films.

Want Esquire delivered on the daily? Sign up for our morning newsletter.

Subscribe Here

But if any year is the year of Sam Jackson, 2019 looks to be it. In addition to his upcoming Marvel work, he will star in the sequel to 2000’s cult-classic remake of Shaft and handle narration for the much-anticipated docuseries Enslaved. This year also marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of Pulp Fiction, which will be celebrated with hundreds of theatrical screenings and a bevy of appearances and interviews by the man who immortalized Jules Winnfield. The Jackson-led M. Night Shyamalan sequel Glass opened the year atop the box office for multiple weeks, and between that and his Marvel commitments, the actor could spend the first year of his seventies with more weeks at number one than any other working actor in 2019—a remarkable feat for a man who is already the highest-grossing film actor of all time, with his movies accounting for an estimated $13 billion combined.

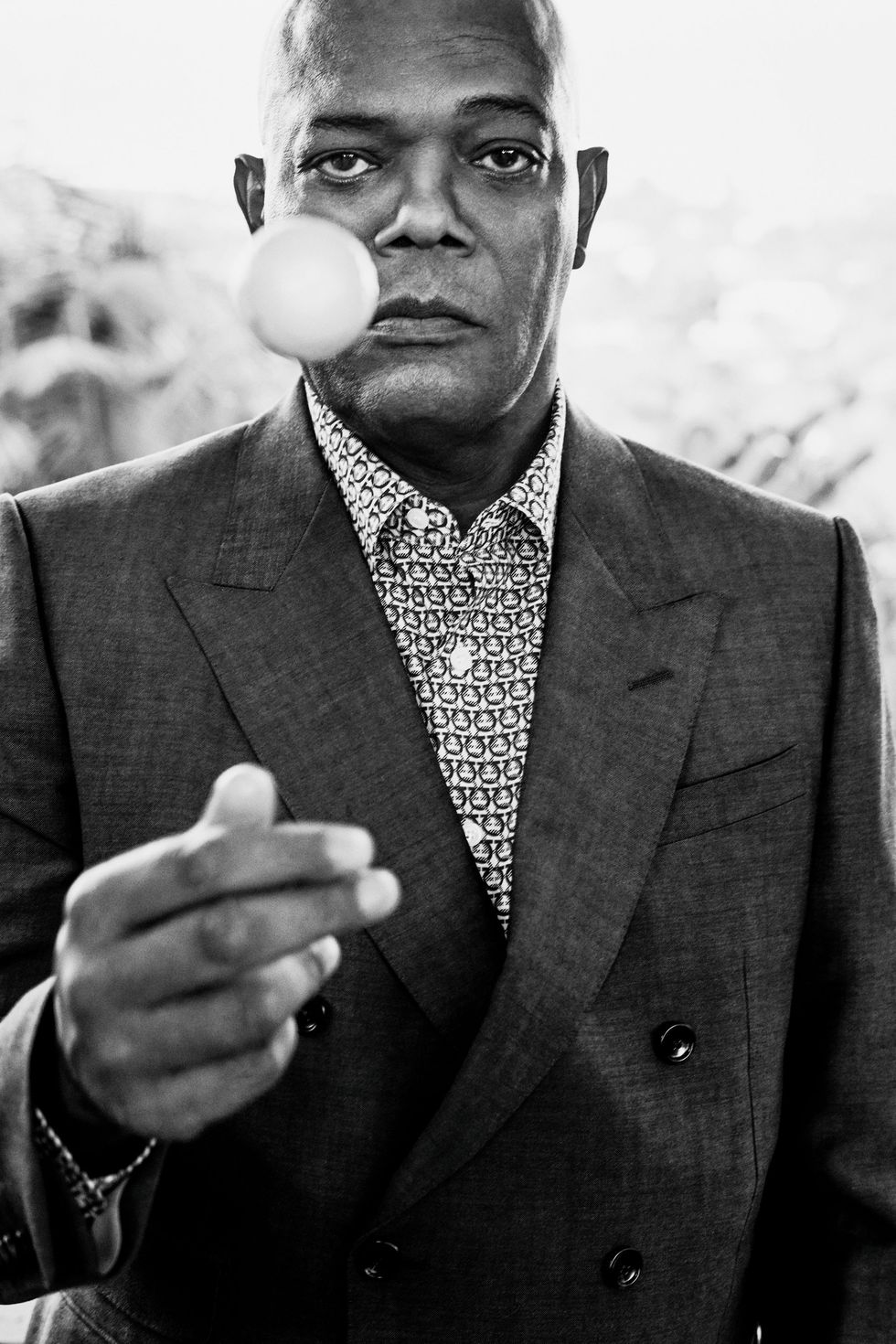

You can think of film acting—and most people do—as the art of creating convincing emotions on command. But fewer recognize it as the art of both nailing takes and saying other people’s words in a way that is so engaging, so clear, so mesmeric that viewers can’t help but stop whatever they’re doing to watch. He is an all-time great at the second and third things and is woefully underrated at the first. Sam Jackson owns words. It doesn’t matter who wrote them. Once he says them, they belong to him, and anyone else who dares speak them is immediately reduced to a cheap imitator. More than flash on film, he has managed to build a legitimate leading-man career out of the journeyman’s trade by showing up to sets on time for nearly forty years and saying his lines correctly and with inimitable style.

This gift is particularly visible in his work with Quentin Tarantino, Jackson’s most frequent collaborator. He has starred in six of Tarantino’s eight features. The director- screenwriter’s ear for dialogue marries the elegant with the profane and is a perfect match for Jackson’s talent for irreverent rhapsody. Jackson received a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination for his performance as Jules in Pulp Fiction, but a legitimate case can be made (and Jackson has made it) that he was a leading actor in that film. Ask any dorm-room Pulp Fiction fan to quote a line from the movie and the odds are high that the one they choose will have been spoken by Jules, a startling fact when you consider that he only appeared at the beginning and the end of the film.

This effect is even more pronounced in Tarantino’s follow-up effort, Jackie Brown, a long-form character study masquerading as an underworld heist flick. Like Jules, Jackson’s character—the Kangol-clad, ponytail-sporting arms merchant Ordell Robbie—is by turns winsome and pestilent. But here Tarantino and Jackson court an entirely more malignant vibe. Whereas Jules is a charming man in a world of stylish people who do horrific things with integrity and humor, Ordell is squarely situated in a province of aging criminals confronting their rapidly crumbling chances to live out their youthful dreams. Jackson cuts his winning smiles, easygoing manners, and lyrical maledictions with a heavy dose of nihilist grief and quiet desperation. His trademark charm offers a thin veil for his unutterable evil. You would like to have a couple drinks with Jules Winnfield. You would quickly leave the bar if Ordell Robbie so much as made eye contact with you.

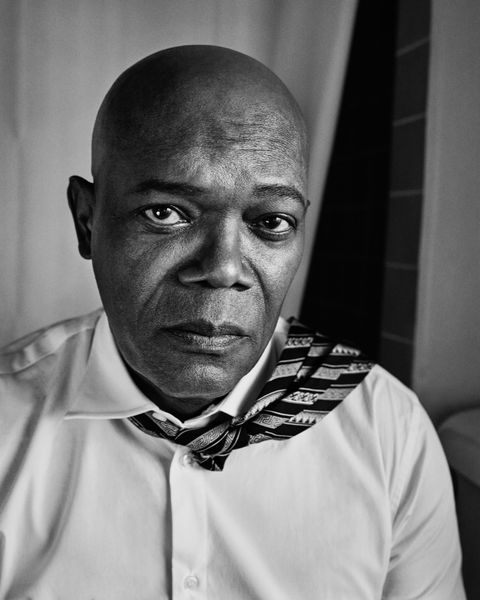

Growing up in legally segregated Tennessee, Jackson says his world was entirely black. He was an only child raised by his maternal grandmother and his mother, a factory worker and later a supplies buyer for a mental institution. His father was largely absent from his life. His aunt, a performing-arts teacher, cast him in plays and placed him in dance classes, which he ultimately came to love for the applause most of all. “You hear the claps,” he tells me, “and that shit is like ego food.” He also played multiple woodwind and brass instruments and harbored dreams of becoming a jazzman until he discovered in the eleventh grade that he lacked the ability to improvise. He entered Morehouse College, in Atlanta, just as the famously persnickety HBCU was opening its gates to a wider variety of students. The decidedly working-class Jackson found himself alongside stern, Afroed, black-fisted men newly returned from the war in Vietnam and carrying a radical militancy that made sense to the young Tennessean who had been warned as a child not to even look white people in the eye.

Jackson quickly fell into student activism, helping to take over an administration building in an attempt to secure a black-studies course and greater black representation on the board of trustees. Among the hostages in the multiday siege was Martin Luther King Sr., whom they had to let go because he was having heart trouble. For his role, Jackson was expelled in his junior year, but the event would only serve to energize him. He slept in the office of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and joined forces with H. Rap Brown and others in a scheme to steal white people’s credit cards and use them to stockpile weapons for what he thought was an inevitable race war. Meanwhile, his friends and associates were dying in “mysterious” automobile explosions.

Providence intervened in the form of two FBI officials who visited Jackson’s mother to tell her that her son was under surveillance, and that if he didn’t leave Atlanta, he would be dead within months. She quickly shipped him off to live with an aunt in Los Angeles, where he worked for the county, smoking weed and dropping acid for a time before deciding to return to school and focus on acting. Soon he was in New York City, auditioning for plays and struggling in theater alongside a tight-knit group of actors that included Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman, Angela Bassett, Bill Nunn, Laurence Fishburne, and LaTanya Richardson, his wife of nearly forty years. His drug use soon got the better of him, however. One week after leaving rehab, he took on the role that would launch his career, that of Gator, Wesley Snipes’s crack-addicted brother in Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever (1991). So powerful was Jackson’s performance that the Best Supporting Actor category was created at Cannes just so he could receive the award.

A scant thirty years and more than a hundred movies later, we are sitting in that country-club dining room and he is saying things like “Engage your core.” Glass, the much-awaited sequel to 2000’s gritty superhero epic Unbreakable, hit theaters in January; he is reprising his role as Nick Fury in the upcoming films Captain Marvel and Spider- Man: Far from Home (we’re pretty sure that’s it for his Marvel movies); and the Brie Larson–directed Unicorn Store is slated for Netflix in April. I got to sit down with Jackson over breakfast while Don Cheadle hawked his latest project on the screen above us and members occasionally smiled at us, stared at us, and quickly looked away when caught.

You have a way of making the most out of whatever character you’re given, no matter how small the part. How do you do that?

You show up. It’s like when I had that job in Coming to America. [Jackson had a bit part as a stickup man.] It was like, all right, I have to make the dude compelling. He can’t be just a motherfucker running in here with a shotgun. It’s got to look like he’s desperate. He’s got to look like he’s serious in the middle of this comedy, and he’s got to be dangerous.

You did the same in School Daze, where you represented this element that was outside the gates of a historically black college.

Interesting enough, those were the dudes that I hung out with when I got to Morehouse. My mom dropped me off and I saw a basketball court up the street. So I stopped in the beer store, bought a quart of beer, walked across, asked who was up next. And I balled with them, hung out with them that night, to the point that they didn’t know I went to Morehouse until they saw me at a dance.

I’ve heard you say that you got radicalized at Morehouse.

My class, ’66, was famously the first class of sort of street niggas that they let in. It had to do with folks like Stokely Carmichael, who was in and out of there speaking. And I was radicalized from both ends. From the black end with Stokely, Rap, and those guys, and the Vietnam vets, and I had an English professor who was driven to Morehouse on the magic bus with Ken Kesey. And then that was when I started dropping acid, and hanging out with him, and finding out what was happening in Berkeley, and then the white parts of the world. My whole existence had been black. I didn’t have a white teacher till I got to Morehouse.

You came up during real segregation.

It was normal. That was the way of the world. I lived in a black world. My teachers were black. I went to school with black kids. I only interacted with white people when I went to work with my grandfather, who worked for white people.

What was that like?

It was always scary for him, because I was that stare-at-white-people dude. I didn’t drop my head. He said, “Yeah, this boy got a little backbone.” The only other time I saw white people was when I went to town. That was it. We had our own black movie theaters in Chattanooga: Liberty and the Grand.

What are some of your earliest memories of seeing movies?

I would go to the movies on Saturday morning and we’d watch cartoons for like an hour. And then they’d have a serial like Buck Rogers. And then they would have the kiddie double feature, Francis the Talking Mule or some shit. And then the serious movies would come. . . . I always remember these Sidney [Poitier] movies because they were always so strange to me. He got killed all the time. And I would ask my mom, “Why?”. . . I’m like, “What the fuck?”

As a kid, did you look at movies and think, I want to do that!?

We looked at movies and went home and redid the movies. We pretended to be whatever we had seen that day. But I wanted to be a marine biologist.

That was actually my fantasy career growing up too!

I wanted to be the black Jacques Cousteau, because I loved 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

I thought those guys were so cool, just out at sea, chilling, looking at starfish and shit.

And I loved all those pirate movies. I wanted to be on a boat out in the ocean. I always thought the inner space was a lot more interesting than outer space.

I always ask people in my family this: Did growing up in segregation make you feel angry?

I don’t think I was ever angry about it. I’m angrier now about it than I was then just because I see these guys and I know these are the same guys: Trump and all those assholes, Mitch McConnell. But they’re the same fucking guys. And when I hear their voices, I hear the same voices. Those twangs where they didn’t specifically call you “nigger,” they said “nigra.” “The nigras.” There was no doubt about where they stood, that you were never going to be their equal and, if possible, they were going to make sure you never had as much shit as they had. And they were worried about the chasteness of their women, and miscegenation, and not having enough of them, there being more of us than there are of them.

Your first film was Ragtime in 1981. What was that like?

Awesome. It was like, going to London, that was my first time in Europe. It was a whole ’nother set of circumstances, being in the world and seeing what that world was. We used to sit and talk with James Cagney at lunch. That was his last movie. That was a big, big experience, figuring out that the world wasn’t what I thought it was. I always looked at Britain as this white place. I realized it has West Indian culture that I didn’t know much about. And from them, I connected to the African culture that was there. And then I realized, “Oh, shit. It’s a bunch of black folks that’s been here for a very long fucking time.”

So in some ways it was just seeing the diaspora in a larger sense.

Exactly. And you’re a part of it.

You finally cleaned up when you were back in New York. Why’d you stop?

Tired of getting high, using up that energy. I’d been at Ruben Santiago’s bachelor party drinking tequila all fucking day. On the way home, I decided, “I need some coke so I can even my shit out.” I went by the spot, copped, went home, cooked the shit, and passed out before I had even smoked it, drunk. That’s when my wife and daughter found me on the floor. She called my best friend, who was a drug counselor. I was in rehab the next day. I just didn’t know I was ready to go, but I was ready.

That was in 1989, not long before Jungle Fever?

Jungle Fever was the first thing I ever did without a substance in my body.

That’s ironic, isn’t it?

Yeah, because all those motherfuckers at rehab were like, “You don’t need to do this movie, because you’re going to have triggers.” . . . I was like, “Well, shit, if for no other reasons, first of all, where the fuck are you going to get $40,000 in the next six weeks? And second of all, I will never pick up another drug, because I don’t want to see any one of you motherfuckers ever again.” I hated them. But that was their job. And I made it through that. So significantly, when Gator gets killed at the end of that movie, I always look at it as the death of my . . . active addiction.

Was that cathartic?

Yeah, of course. It’s one of those things where my wife always criticized my acting as being bloodless. She said, “You’re smart. You know the right facial expression. You know the vocal inflection. You know everything to do except how to feel it.”

Do you think she’s right about that?

She was totally right, because I used to act and watch the audience for their response to what I did.

Performing rather than acting.

I understood another thing about being a crackhead and using up your relationships, fucking those things up, and what it meant to hurt the people in your family. Gator was people’s sons, their nephews, their brothers, their daughters. Everybody had a motherfucker that would come to their house and had gotten something from them or stolen something from them, broken their heart in some kind of way.

After that movie, you launched into doing sometimes as many as seven titles a year. A lot of actors don’t think of doing their work that way.

I’ve never understood that whole “I want to do two movies a year” thing. It’s like, you don’t love the job? I want to get up and act every day. And there’s a limited number of acting possibilities in everybody’s lifetime. So I’m trying to maximize my shit.

A lot of actors are concerned about doing quality movies.

What’s a quality movie? What the fuck is that?

You tell me.

Quality movies are movies that make me happy, a movie I would’ve gone to see. I’m not trying to make people cry. I’m not trying to do the profound-storytelling thing. I was entertaining. I used to go to movies to forget my fucking troubles. I used to go to movies to enjoy myself, to get out of my segregated fucking life, to see what the world was like, to travel. I want people to come, smile, laugh, leave that movie going, “Man, that was awesome.” Even if it’s A Time to Kill. It’s a serious subject, but it was something that needed to be told. And that was a way to tell it. And it’s a very different movie from the movie that I went there to do.

In what way?

Well, [my character] Carl Lee kills those dudes because he has to kill those dudes for his daughter so that she’ll understand, “The world is safe for you. And if anybody else does some shit to you, I’ll kill them, too. But I’m your protector. I will do anything to make sure you’re okay.” In the editing of that movie, everything I did that spoke to that got edited out, and it turned to: I killed some motherfucking white people and I connived to get away with it. So when I saw it, I was sitting there like, “Oh, that’s right.” They’re in control of the shit. It’s a director’s medium; they could do what they want to do to make it change. Which leads me to now, when I’m on a movie set and the motherfucker says, “Can we try this?” Sometimes I’ll be like, “Naw.”

That’s why you don’t do multiple takes.

I don’t do more than three. I don’t get to go to the editing room, but you do. And you’re going to put that thing that you asked me to do in there, because that’s the thing you like. So if I don’t do it, I don’t have to worry about you fucking with my performance.

I haven’t seen all your films—I mean, who has time to see every single Sam Jackson movie?—but. . .

I do.

Which roles do you love?

I love Mitch Henessey, the dude from The Long Kiss Goodnight. He’s another dude that’s in a job that he thinks is a con. “I’m not really a private detective, but if I can get you to hire me. . .” I just love the sincerity of that dude, who becomes brave in the face of some shit that he knew he shouldn’t even be talking about. I love the teacher in 187, because that’s like my aunt. I understand how hard that job is. And believe it or not, I love fucking Stephen from Django Unchained.

Why?

I mean, the dude ran that fucking plantation. Candyland was his fucking plantation. Leo’s out fighting niggers and doing whatever, running the strip club. Dude’s writing the bills. He’s making sure the crops get planted. He’s making sure the slaves get sold. He runs that place. And he’s been there. His father did the same job he had; his grandfather did the same job he had. And he has this misplaced love for Leo and this stuff because he raised him. He ain’t really got no kids of his own because he ain’t have time to do that. But Leo was basically his kid. And Candyland is his world. He knows outside Candyland, he’s just another nigger on the plantation.

What do you think about all the controversy surrounding Quentin Tarantino’s use of the n-word in that movie?

It’s some bullshit.

All of it?

Of course it is. When we did Pulp, I warned Quentin about the whole “nigger storage.” I was like, “Don’t say ‘nigger storage.’ ” He’s like, “No, I’m going to say it like that.” And we tried to soften it by making his wife black, because that wasn’t originally written. . . . But you can’t just tell a writer he can’t talk, write the words, put the words in the mouths of the people from their ethnicities, the way that they use their words. You cannot do that, because then it becomes an untruth; it’s not honest. It’s just not honest. And half the time, too, there are other ways. And I generally add like at least five niggas to what Quentin has already written, just because I’m talking. I mean, that one sentence to Chris Tucker [in Jackie Brown]: “I hate to be the kind of nigga that do a nigga a favor and then bam hit the nigga up for a favor in return, but I gots to be that kind of nigga.” It’s just one sentence. It’s like boom. But wouldn’t Ordell say that?

Absolutely. But that brings me to the other question: How do you reconcile having once been a radical, stockpiling weapons for a race war, with your life now, on a golf course, doing Capital One commercials?

I’m the same cat. I still got my politics. I still have my anger. But I can’t regulate a bank. I can’t deregulate a bank. I can’t do any of that. It’s been a great revenue stream right now. And because I have that revenue, we’re able to have our names on the fucking wall of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. We’re able to give money to the Children’s Defense Fund. We’re able to dig a well in Africa. But I don’t run around with a film crew and say, “Show everybody what I’m doing.” I just do what I do. It’s not like we’re just building up a stack of cash somewhere for whatever’s going to happen. They might wake up tomorrow and decide that money ain’t the thing. Then what? Everybody you work for you can have a beef with, especially in this business that I’m in, because it ain’t the studios no more; it’s corporations. I’m working with corporations. And all those motherfuckers got issues. But we do what we can. We understand our responsibility. We understand from a revolutionary standpoint what we came from, and what’s going on in the world, and what can we do to make the world a better place or to make the world a better place for a specific group of people that need betterment in that way.

You’ve been vocal about Trump. A lot of people have their beliefs but are careful about stating them, because they don’t want to jeopardize their career.

I think we feel the same way that all of the motherfuckers that hated Obama felt for eight years. So they said all that shit. They put fucking pictures up on the Internet of Michelle sitting with her legs crossed with a dick hanging down. We feel the same way that they feel or they felt about Obama being the man, even though he wasn’t fucking ruining their lives; he was trying to help their lives.

This motherfucker is like ruining the planet and all kinds of other crazy shit. And the people think that’s okay. It’s not fucking okay. And if you’re not saying anything, then you’re complicit. And I wouldn’t give a fuck if I was a garbageman and I had a Twitter account; I’d tweet that shit out. I’m not thinking about who I am and what my job is when I do that shit.

Do you worry about antagonizing fans?

I know how many motherfuckers hate me. “I’m never going to see a Sam Jackson movie again.” Fuck I care? If you never went to another movie I did in my life, I’m not going to lose any money. I already cashed that check. Fuck you. Burn up my videotapes. I don’t give a fuck. “You’re an actor. Stick to acting.” “No, motherfucker. I’m a human being that feels a certain way.” And some of this shit does affect me, because if we don’t have health care, shit, and my relatives get sick, they’re going to call my rich ass. I want them to have health care. I want them to be able to take care of themselves. This is how I feel. And I count to one hundred some days before I hit “send,” because I know how that shit is.

So you’re seventy?

Mm-hmm.

What are you getting better at as a person?

I guess opening up. I talk more to my wife and daughter than I used to. I ask them more about their shit, because it’s always about my shit. I’m getting better at talking to them about their lives and what they are doing and how they feel.

What brought about that change?

I guess age and the fact that we’re more apart than we used to be. It’s like my wife—she’s got to be in New York [doing To Kill a Mockingbird on Broadway] for a year. So it’s not like she can come and hang out with me while I talk to her.

How much longer are you going to work?

Till I can’t do it. Michael Caine’s still acting, right? It’s acting. It’s not like I’m digging a ditch. I go on set, do some shit. I go back and sit in my trailer for two hours watching TV, eat a sandwich, read. And I go back and do ten more minutes and go sit down some more. So, yeah, it’s a great job.

What have you gotten better at as an actor over the years?

Relaxing into it, not being tense about getting there and getting the big scene. I’m getting better about being patient with people on the other side.

I’ve heard stories.

Really? Yeah, well. . . My agents and managers tell me my biggest problem is I expect everyone to be as prepared as I am. And I do. We came here to do something. Let’s do it.

What is your favorite scene?

I guess it would be actually the ultimate scene that everybody turns out to love so much, and it’s the diner scene in Pulp Fiction. Everybody loved the killing ones, but the diner scene, just because there’s so much going on when John [Travolta] and I are sitting there having that conversation prior to what happened, and the bullets not killing us, and he’s making this decision about walking the earth just to see what’s going on. So by the time Tim [Roth] gets there and I have an opportunity to do that speech again, the same speech that I’ve been killing people with, and make it make sense in a whole ’nother kind of way, and, one, it’s just the biggest threat you’ve ever heard in your life. And the next, the dude’s like sitting there making a revelation about who he is and where his place is in the world, and who he actually is. He said, “I’d love to be the shepherd, and that would be great.” They said that they didn’t know how the movie was supposed to end until I did that scene. But they had no idea that that’s what all that shit meant until I did it.

I just teared up a little bit, because that is what makes that scene work: that no one—no one in the audience, no one in the movie, no one anywhere—knows what any of it means until that speech is delivered.

Exactly.

Why didn’t the bullets hit you?

Deus ex machina. And that motherfucker wasn’t that good a shot.

So what do you have planned for the rest of the day?

Pilates and then acupuncture.

L.A. life, man.

It’s not just L.A. life—this is my life. I got to work this body.

This article appears in the April 2019 issue of Esquire.

Subscribe Here