Between The Elephant And The Dragon 4: World War II

This is part 4 of a history series exploring the relationship between Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam.

The Winds of War

By the 1930’s events taking place north of Indochina would have serious repercussions for the region for the next six decades.

The winds of war were blowing across Asia long before September 1939. Between 1904-05 Japan had inflicted an embarrassing defeat on a major European power, Russia. This new expansionist ‘supernova in the east’ took control of the Korean peninsula and set eyes on China, moving in from 1931 and arguably beginning the Second World War following the ‘Marco Polo Bridge Incident’ and Japanese capture of Beijing, Shanghai and the Chinese capital of Nanjing in 1937 .

The Chinese Community

The 19th and early 20th century had seen massive upheaval in China, rebellions, war and famine finally ended the 2000 year old Qing dynasty in 1912. A mass exodus of Chinese, mostly young men, spread across the whole Pacific region during this period.

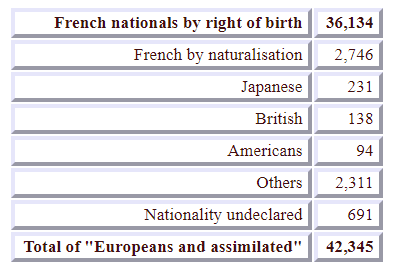

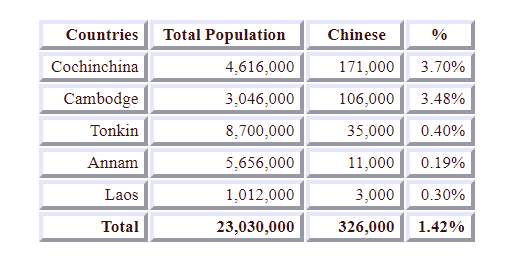

A 1937 French census showed there were almost 10 times as many Chinese immigrants in Indochina than there were French-born.

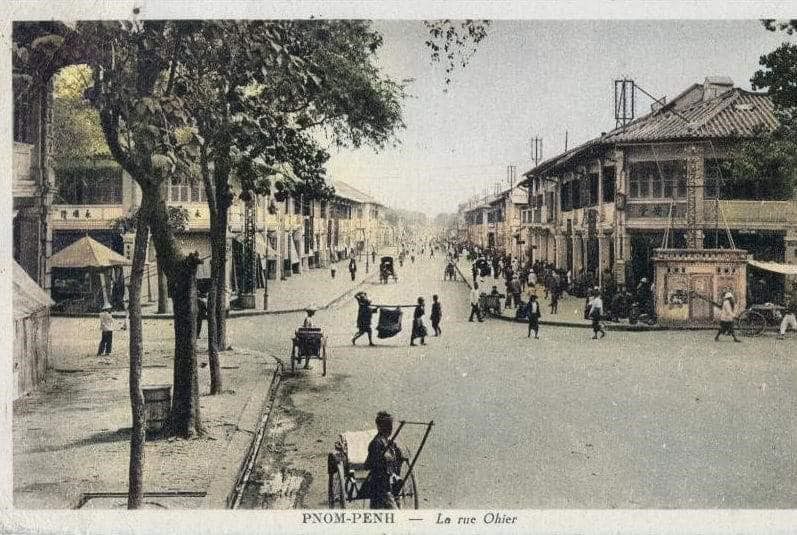

The new arrivals in Cambodia, mostly known as Teochew, quickly set themselves up as middlemen, traders and money lenders. Although there were issues with the French, mainly over the unwillingness to pay taxes and the control of the lucrative opium trade, the Chinese were soon established as a trader class in Phnom Penh. The ‘Chinatown’ of the capital was the Quartier Chinois, to the northwest of the Royal Palace around modern-day Street 13.

Although mixed marriages were very common, many customs and traditions were kept, or merged with the Khmer, and the newcomers were not universally accepted. The majority of modern Khmer people who trace some Chinese ancestry come from these immigrants.

One example of how the mood may have been, came from Anglophile King Vajiravudh (Rama VI) of Siam who published a Thai newspaper article in 1914 titled “The Jews of the East”. He accused Chinese immigrants in Thailand of excessive “racial loyalty and astuteness in financial matters.” The king wrote; “Money is their God. Life itself is of little value compared with the leanest bank account.”

The descendants of these Chinese traders would face persecution across much of Southeast Asia for all of the 20th century.

Japanese Expansion

In mainland China a three-way struggle was being fought between imperial Japan, nationalist forces under the control of Chiang Kai-Shek and the Chinese Communists (who themselves were occasionally infighting and making purges within their ranks).

The Chinese nationalist government was importing arms and fuel into the Vietnamese port of Haiphong and into Yunnan province to use against the Japanese. Japan wanted to stop this, but remained cautious.

The alliance between imperial Japan and Nazi Germany since 1936 was written for a common enemy in Stalin’s Russia, and Tokyo did little to provoke European interests in Asia following the fall of France in the summer of 1940.

The new Vichy government of Marshall Petain was permitted to keep most of France’s colonies, but unlike those in the Mediterranean and near-East, Indochina was far away and isolated. As other French colonies in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean joined the Free French under Charles De Gaulle on the Allied side, Indochina remained loyal to Vichy. To appease the Japanese, the supply routes to China were cut and a small Japanese force allowed to garrison in the colony.

However, it was Bangkok, not Tokyo who attacked Indochina.

Franco-Thai War 1940-41

Major-General Plaek Pibulsonggram (Phibun), the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, (changed from Siam in 1939) had taken power in 1938, following a revolution in 1932 and a series of counter-coups that moved the kingdom from an absolute to a nominally constitutional monarchy. A great admirer of Italy’s fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, the de-facto military state was nationalist, anti-Chinese and pro-Japanese.

He gambled that Vichy France could not resist a Thai military campaign to recover parts of Cambodia and Laos lost in 1907. In October 1940, the military forces of Thailand attacked across the border with Indochina and launched the Franco-Thai War.

France was at a disadvantage from the offset. Around 48,000 Indochinese troops and 12,000 French and Foreign Legionnaires faced a larger Thai military that had been modernized with ground, air and naval weaponry from Britain, USA, Sweden and Japan.

The superior Royal Thai Air Force, which included Japanese made Mitsubishi Ki-29 and Ki-30 and US made Martin B-10 bombers, along with Curtiss P-36 Hawk fighters and older Vought O2U Corsairs conducted daytime bombing runs over military targets in Vientiane, Phnom Penh, Sisophon, and Battambang with impunity.

The French, with an inferior Armée de l’Air retaliated with their own air attacks with less than equal results. The activities of the Thai air force, particularly in the field of dive-bombing, was such that Admiral Jean Decoux, the governor of French Indochina, grudgingly remarked that the Thai planes seemed to have been flown by men with plenty of war experience.

On 5 January 1941, following a French attack on Aranyaprathet launched from Poipet, the Thais launched an offensive on Laos and Cambodia. The French responded, but were beaten back by the better-equipped Thai forces. The Thai army swiftly overran areas of Laos, but the French forces in Cambodia managed to rally and offer more resistance.

At dawn on 16 January 1941, the French launched a large counterattack on the Thai-held Cambodian villages of Yang Dang Khum and Phum Preav, initiating the fiercest battle of the war. Poor co-ordination and non-existent intelligence against ready and waiting Thai forces saw the French retreat back to Sisophon. The Thais were held back from advancing by the artillery of the Foreign Legion.

As the land war situation deteriorated, France still had a superior navy. Admiral Decoux ordered all available French naval forces in the Gulf of Thailand to prepare for an ambush and offensive. The plan given to Capitaine Vaisseau Regis Berenger was to support a planned offensive against the Thais advancing into Cambodia “Attack the Siamese coastal cities from Rayong to the Cambodian frontier, compelling the Siam government forces to retreat from the Cambodian frontier”

Early in the morning of 17 January, a French naval squadron, along with naval aircraft flying out of Ream airbase, caught a Thai naval detachment by surprise at anchor off Ko Chang island. The subsequent Battle of Ko Chang resulted in the sinking of five Thai warships with just 11 French sailors killed. Fearing the war would turn in France’s favor, the Japanese intervened, proposing an armistice agreement.

A week later on 24 January, Thai bombers raided the airfield near Siem Reap. The last Thai mission bombing Phnom Penh commenced at 07:10 on 28 January, when the Martins of the 50th Bomber Squadron set out on a raid on Sisophon, escorted by thirteen Hawk 75Ns of the 60th Fighter Squadron. At 10.00 the same day an armistice was declared and a peace treaty was signed in Tokyo on 9 May.

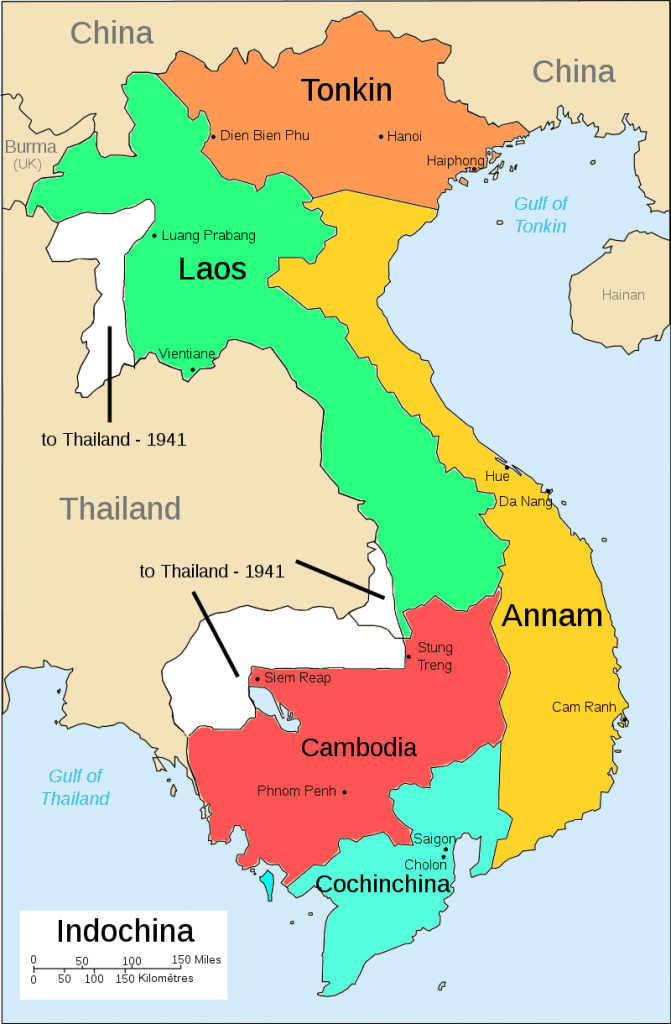

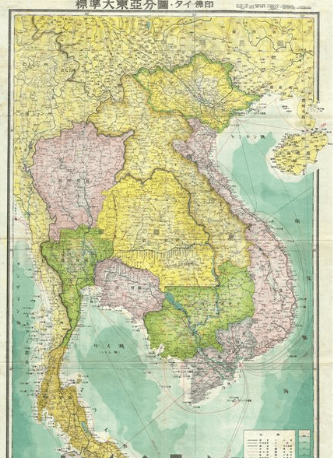

Japan forced the French to accept a peace treaty that returned the disputed territories of western and northwestern Cambodia back to Thai control. Battambang, Banteay Meanchey, Oddar Meanchey, Preah Vihear, Siem Reap, and parts of Kampong Thom and Stung Treng were put under Thai control. While Cambodia was permitted to keep Angkor Wat, Cambodia had again lost around 1/3 of the country to the Thais.

The Thais were jubilant, although compared with what was taking place elsewhere in the world, the casualty rates on both sides were low. The French army suffered a total of 321 casualties, of whom 15 were officers. The total number of missing after 28 January was 178 (six officers, 14 non-commissioned officers and 158 enlisted men). The Thais had captured 222 men (17 North Africans, 80 Frenchmen, and 125 Indochinese).

The Thai army lost 54 men killed in action and 307 wounded. 41 sailors and marines of the Thai navy were killed, and 67 wounded. At the Battle of Ko Chang, 36 men were killed, of whom 20 belonged to HTMS Thonburi, 14 to HTMS Songkhla, and two to HTMS Chonburi. The Thai air force lost 13 men. The number of Thai military personnel captured by the French was just 21.

The Teenage King

King Monivong, who had supported French interests all his life, fell into a deep malaise and retired to his royal residence on Bokor mountain, where he died on April 23 or 24, 1941, at the age of 65.

It was not the best of times for another bitter royal succession. The Japanese were demanding that 8,000 soldiers be based in Cambodia, a gloating Thailand were celebrating the first ever Southeast Asian victory over a European power, and the rivalry between the Sisowath and Norodom branches of the large royal family was always in danger of spilling over into civil war.

The French decided to install a 19-year-old prince, who was of both houses Sisowath and Norodom, supposedly to heal the rift. Despite these claims, it was believed by all that the young Norodom Sihanouk was chosen for his youth and inexperience, which would make him more malleable to French interests. This would later prove to be wrong.

World At War

A Japanese force arrived in Cambodia in August, and as the reduced kingdom offered little more than a conduit westward on the road to India, the administration was left intact. In Tokyo plans were already being drawn up for the most audacious strikes in history.

On December 7, 1941, at 7:48 a.m. Hawaiian Time Pearl Harbor base in Hawaii was attacked by 353 Imperial Japanese aircraft (including fighters, level and dive bombers, and torpedo bombers) in two waves, launched from six aircraft carriers.

Simultaneous attacks were launched on US bases in the Philippines, Guam and Wake Island and on the British Empire in Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong. Japan was now at war with the US and British Empire.

The 3 Hour War

Also on December 7 Japan sent a formal request to Thailand to allow free passage for Imperial troops to attack the British in Burma. A formal alliance was also proposed, but the matter needed a reply within 2 hours. After the Thai government failed to come up with a response, Japanese forces launched an attack on four coastal provinces. Around 3 or 4 hours later the Thais capitulated. On January 25, 1942, the Thais joined the Japanese and declared war on the US and Britain.

In a strange twist, the Thai ambassador in Washington DC, Seni Pramoj, refused to deliver the official declaration, therefore, the United States did not declare war on Thailand. With American assistance, Seni, a conservative aristocrat (his great-grandfather was Rama II) was another Oxford educated Thai, with well established anti-Japanese credentials. He helped organize the Free Thai Movement in the United States, recruiting Thai students to work with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Seni was able to achieve this because the State Department decided to act as if Seni continued to represent Thailand, enabling him to draw on Thai assets frozen by the United States.

Rising Nationalism in Indochina (1942-44)

Although the colonial government had been left in charge, Japanese calls of “Asia for the Asiatics” found an audience among a small, but growing group of Cambodian nationalists. When a prominent, politically active Buddhist monk named Hem Chieu, was arrested and defrocked by the French authorities in July 1942, the editors of the nationalist Nagaravatta newspaper led a demonstration demanding his release. They apparently overestimated the Japanese willingness to back them, and the Vichy French authorities quickly arrested the demonstrators and gave Pach Chhoeun, one of the Nagaravatta editors, a life sentence. The other editor, Son Ngoc Thanh, escaped from Phnom Penh to Bagkok and turned up the following year in Tokyo.

Acceptance of the Japanese presence had mostly ensured that atrocities carried out in other parts of Asia were not carried out elsewhere in Asia. The Thais, satisfied for the moment with regaining the provinces ‘lost’ in 1907, turned to claiming back parts of Burma long considered to belong to Thailand.

The resistance to both France and Japan was predictably centered around the ever-restive region of Tonking, northern Vietnam.

Nationalist Vietnamese groups, both communist and non-communist had long been based over the border in China’s Yunnan province. A man known as Quốc had been serving as a Southeast Asian advisor to the Chinese Communist Party since around 1938. He had changed his name (one of many aliases) to what translates as ‘He who has been enlightened (by) will/spirit bright’. We know him as Ho Chi Minh, head of the Indochinese Communist Party and leader of the Viet Minh rebel army.

Ho Chi Minh returned to Vietnam in 1941 and was soon imprisoned under the orders of the Chinese nationalist General Chiang Kai Shek. Ho spent 18 months in prison, before his release was arranged. By 1944 the Việt Minh claimed to have 500,000 members of whom 200,000 were in Tonkin, 150,000 in Annam, and 100,000 in Cochinchina.

The Final Days of War (1944-45)

With the war looking winnable, the Allies met in Cairo in November 1943. President Roosevelt, who loathed Charles De Gaulle did not want to see the French control a post-war Indochina, and offered the region to Chiang Kai Shek to govern under a Chinese administration. The Generalissimo’s reply was said to have been “Under no circumstances!”. A terrible famine took hold in Vietnam over 1944-45 with anywhere between 600,000-2 million Vietnamese dying of starvation. The French and Japanese blamed each other, along with the Viet Minh.

The war had mostly passed Cambodia by until the final months. The Thais, worried that their alliance with Japan may cost them the reclaimed provinces in Laos and Cambodia gave support to Poc Khun*, an aristocratic Khmer, and related to the royal family through marriage, who founded armed group in Bangkok in 1944, and called it the Khmer Issarak. *Think this is Pach Chhoeun, who was imprisoned by the French in July 1942.

American air raids hit the Vietnamese ports at Haiphong and Saigon, while on 7 February 1945, bombing of Phnom Penh by the USAF saw Wat Ounalom hit by mistake, killing several monks and civilians.

On 9 March the Japanese removed the French administration in Indochina and interned most French military and administrative personnel. During ‘Operation Bright Moon’ around 15,000 French soldiers were held prisoner by the Japanese. Nearly 4,200 were killed, with many executed after surrendering – about half of these were European or French metropolitan troops. Practically all French civil and military leaders as well as plantation owners were made prisoners. Emperor of Annam, and the last of the Nguyễn dynasty was installed as a Japanese puppet in the newly created Empire of Vietnam.

In Phnom Penh, King Sihanouk was allowed to take full control, and on 12 March he voided all agreements with France and proclaimed the independence of the Kingdom of Kampuchea.

Son Ngoc Thanh was brought back from Japan to serve as foreign minister, possibly to serve Japan’s interests if the king was found to be too pro-French. Thanh’s time abroad had changed his politics to that of a republican fascist. Following the Japanese surrender on August 15, he became Acting Prime Minister and quickly made himself unpopular among the elite.

Japanese Surrender

A power vacuum was left after the Japanese surrender in Vietnam. In July 1945 at Potsdam, Germany, the Allied leaders made the decision to divide Indochina in half—at the 16th parallel—to allow Chiang Kai-shek to receive the Japanese surrender in the North, while Lord Louis Mountbatten would receive the surrender in the South.

The Allies agreed that France was the rightful owner of French Indochina, but because France was critically weakened as a result of the German occupation, a British-Indian force was installed in order to help the French Provisional Government in re-establishing control over their former colonial possession. However, the US did not fully support the return of the French as a colonialist power, and pushed for reforms.

The Japanese began handing over weapons to the Viet Minh, who seized control of the major cities. The US, which had been secretly supporting the Viet Minh in their fight against the Japanese had sympathy for the communists.

On August 22, American intelligence officer Major Archimedes L. Patti arrived in Hanoi to secure the release of American POWs held by the Japanese in Indochina. Accompanying Patti was a French team headed by Jean Sainteny, ostensibly in Indochina to care for French POWs. Ho Chi Minh warned Patti that Sainteny’s real objective was to reassert French control over Vietnam.

Patti reported to his superiors in China that “Việt Minh strong and belligerent and definitely anti-French. Suggest no more French be permitted to enter French Indo-China and especially not armed.” Patti refused to allow the release of 4,500 French soldiers imprisoned in Hanoi by the Japanese.

On September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. He quoted the American Declaration of Independence which had been supplied to him by the OSS (the American pre-CIA intelligence department)– “We hold the truth that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among them life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. This immortal statement is extracted from the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America in 1776. These are undeniable truths.” One week later a force of 150,000 Chinese troops arrived to take the Japanese surrender and hold the peace, although this army was made up mostly of peasants who looted and pillaged their way down from the border.

Ho Chi Mih and OSS officers, 1945

British-Indian troops landed in Saigon on September 15 and began the process of handing Indochina back to the French.

They faced resistance and there were several bloody clashes between the European and Viet nationalists. Named Operation Masterdom by the British and the Southern Resistance War by the Vietnamese, the conflict between British and Indian troops lasted for over 6 months before British troops pulled out in March 1946. Around 40 British and Empire soldiers were killed, with 6 members of the small contingent of British troops left in Vietnam being the last, after they were caught in an ambush in June.

The First Indochinese war (the Anti-French Resistance War) officially began in December 1946. Tactics honed and lessons learned would go on to shape Ho Chi Minh’s independence struggle for the next 30 years.

A detachment of Gurkha troops arrived in Phnom Penh on October 8, 1945, and managed to avoid any confrontation. On October 15, General Jacques-Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, Commander of the French Far East Expeditionary Corps, arrived from Saigon. He summoned Prime Minister Tanh and immediately arrested him and sent him back to France.

On January 4, 1946, an agreement was struck which saw Cambodia as an independent kingdom within the new Indochinese Federation. France retained control of foreign relations, so Cambodia could not join the United Nations or have embassies with other countries. All defense and military affairs were also placed under French command.

Although the protectorate had ended, the new federation pleased next to no one. Sihanouk, looking for full independence on his terms begrudgingly began the democratic process, as required by the new Fourth Republic government in Paris, and approved of by the US.

Meanwhile, the Khmer Issarak, which was mostly right-wing at the time and supported by Bangkok, took up positions along the Thai border areas. The occupied territories taken in 1941 were returned in 1946 as a condition of Thailand joining the United Nations.

To the east the Viet Minh had already began using Cambodian jungles as bases to fight the French, and were busy recruiting and training the “Khmer People’s Liberation Army” and spreading Marxism.

With the French still holding a central administration together, the combination of indecisive leadership and interference from across the borders meant that Cambodia was preparing to tear herself apart, as had been the case since the last kings of Angkor.

Thank You. Very interesting, continue

Thank – you , to all involved that made this post possible !

And all 4 editions ave easy access !

Very informative , authentic pics as well !

( I became ill in Oct /Nov & didn’t see the original post ,BUT I did see Part 4 , &

that’s all that matters ) !

The French introduced brothels & bagets to Cambodia,both very tasty