Discover more from Candy for Breakfast

The snowball dance is a torture ritual for adolescents, invented by the Josef Mengele of middle school.

If you’re unfamiliar with this form of cruel and unusual punishment, in a snowball dance, a large group of kids—usually early teenagers, twelve or thirteen-ish—stand in a circle around one slow-dancing couple like witnesses to a gruesome car crash. Eventually, the torture master (a.k.a. DJ) shouts “Snowball!,” and the dancing couple splits, each of them choosing a new dance partner from the surrounding spectators. The splits continue every thirty seconds or so, until all of the participants are either on the dance floor or hiding in the bathroom.

There’s really no way to win at a snowball dance. Get chosen too late and you’re indelibly marked as a loser, doomed to shuffle around shamefully as what was once a large circle of your peers becomes just a few scattered dots, like pustulous zits on the dance floor’s face. But get chosen too early and you’ll face an equally terrible fate: forced to “dance” for untold minutes to Kelly Clarkson’s 2002 single “Moment Like This” as your gawk-eyed peers stare at your awkward swaying. As with nuclear war, the only winning move in a snowball dance is not to play, which is why no one has ever engaged in either activity voluntarily, and why equivalent resources have been expended towards avoiding both.

Snowball dances, like JNCO jeans, blessedly disappeared from my life around the time I graduated from middle school. But their absence hardly improved my relationship with dancing.

In college it seemed like dancing was just a pretense for hooking up, and though I wasn’t incapable of getting girls to kiss me in other contexts, on the dance floor I felt like I was the only one who hadn’t been given the instruction manual. I’d watch in horror as boys far uglier and dumber than me would transition seamlessly from guzzling vodka to guzzling some girl’s tongue. I didn’t understand a single step of this process. How did you coordinate grinding with someone, let alone kissing them, without being able to talk to them first?

Now, of course, I understand that I was probably just overthinking everything. There was no secret code everyone was using to coordinate, just a bunch of drunk idiots not-always-consensually groping at each other. At the time, though, every dance floor was a place of stress and anxiety. I was always disappointed when the pregame was over and the walk to the real party began. Half the time, I’d peel off from the group and listen to sad, very non-danceable music alone in my dorm room. Sometimes I’d think about the excuse I’d use if someone asked me why I didn’t make it to the party, but nobody ever did.

I went to my first rave, a few months after I graduated from college, because I had just moved to a new city and was willing to go pretty much anywhere anyone invited me. This was in Detroit, techno’s birthplace in the mid-eighties and still, in 2012, home to one of the country’s most flourishing electronic music scenes. Not that I had any interest in electronic music, unless you counted “I Knew You Were Trouble” and the other Max Martin-produced songs on Taylor Swift’s just-released Red. I’m not sure I even knew what a rave was, honestly. I probably Wikipedia’d the term before I went.

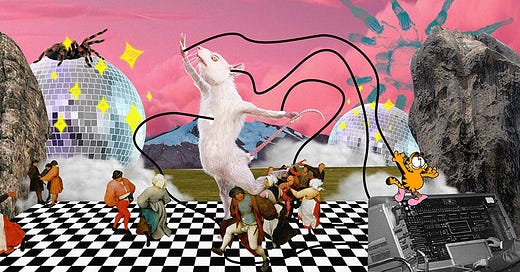

The rave was in an old warehouse, the last upright structure on a block full of abandoned buildings in various stages of decomposition. Inside it was bright and loud and by far the most crowded space I’d found in Detroit thus far. I didn’t like the music, which sounded like a dial-up modem, but I didn’t dislike it either. It existed on a plane where liking or disliking it weren’t even concepts that applied. I danced without trying to, without even thinking about it. The music somehow bypassed my brain and forced my body to move. I was like one of those lab rats that gets wires run into its brain and can be made to move its paws when the scientists press a button. I wasn’t self-conscious, because only a brain can be self-conscious, and I was just a body. It was revelatory. I went back over and over and over and over.

I was, unknowingly, only the latest participant in an ancient tradition of ritualistic dances with no purpose but ecstasy. I had always associated dancing with courtship—grinding to Usher in the middle school gym was just the modern version of linking arms with the girl next door at the neighborhood square dance, or showing off your waltz skills in a prince’s palace in 18th century Austria. But for every small-town sock-hopper or Austro-Hungarian debutante, there’s been an ancient Grecian hoping their frenzied gyrations will bring them closer to Dionysus, or a devout Shaker finding so much pleasure in movement that he doesn’t even mind being celibate.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Europe was plagued by periodic fits of “dancing mania,” wherein the citizenry would bounce and bob uncontrollably in public spaces, often until collapsing from exhaustion. There is still no consensus among historians as to the cause of dancing mania, with theories ranging from accidental ergot poisoning to social contagion to curses from angry demons. In Italy they called it “tarantism,” and its victims were said to have been bitten by a tarantula, with wild dancing the only antidote. This is almost certainly where the tarantella, a still-popular folk dance, gets its name.

Perhaps we need angry demons or spider bites or the power of Dionysus because letting yourself go like that without a good excuse is just too embarrassing.

Certainly there’s something terribly embarrassing about rave culture—the whole thing looks pretty stupid from the outside. Honestly, it looks a little stupid from the inside too. Rave culture was always cringe, but at least in its early days it was wrapped in the soft glow of all things vaguely countercultural. There’s no such thing as the counterculture anymore, though. EDM festivals are run by giant corporations, ketamine is advertised on billboards, and our parents pay thousands of dollars to take MDMA and talk about their divorces in Upper West Side therapists’ apartments.

But the cringe isn’t just an incidental part of rave culture. The cringe is the point. A rave is an embarrassment-free zone because everyone there has already made an intentional choice to look and act so dumb that it’s impossible to be embarrassed in comparison. Even at my most self-conscious, no matter how stupid I thought I looked, no matter how grotesquely I thought I was dancing, I knew I couldn’t possibly be the stupidest-looking person in the room. I couldn’t even possibly be in the top 10%.

The defining elements of rave culture—the ridiculous outfits, the over-the-top lovey-doveyness, the all-encompassing good vibes that prevent you from noticing when the music is horrible, and, yes, the drugs—are all attempts to bring participants back to a childlike state. Children are never embarrassed, they never think anything is cringe, and it would never occur to them to dance in any other way than with abandon.

It’s been a long time since I went to a rave. They got old, as even the purest pleasures do when repeated often enough, and so did I.

After all, so much of their initial power was the discovery that these places—the physical spaces themselves, and the mental spaces they brought me to—even existed. After a while, just knowing the latter was possible meant I didn’t have to go to the former to get there. I got the message, so I hung up the phone.

I think back to my days of dance anxiety and it’s hard to remember what all the fuss was about. Truth is there probably never were any eagle-eyed watchers observing my dance moves and readying their criticism—certainly not at frat parties or prom, and probably not at snowball dances either. Even in those dance panopticons, everyone else in the circle was probably too worried about their own fates to pay much attention to the kids in the center. Besides, it’s pretty much impossible to slow dance wrong in middle school. Even when you’re “dancing,” you’re mostly just standing there.

I still think snowball dances should be illegal and their inventors hauled before a war crimes tribunal. But if I was somehow forced into one now, I probably wouldn’t hide in the bathroom. I’d pretend I was a little kid, or had been bitten by a spider, or possessed by a spritely demon. And maybe, after a couple songs, I’d start to feel like all of those things were actually true.

Also cringe: asking for likes—but I’m doing it anyway. If you enjoyed this piece, consider giving the heart button at the bottom a tap.

Subscribe to Candy for Breakfast

Funny feelings, weird careers, making art, American history, and how to be alive.