For many reasons, Hawaii has become known as a vacation destination for people from around the world, yet most don’t know much about its rich and complicated history. The following is based on a discussion guide created by The Foundation for Global Sports Development.

When was Hawaii first populated?

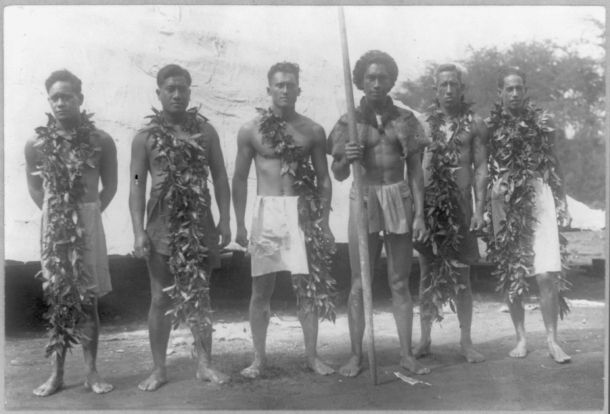

Early South Pacific voyagers arrived in Hawaii around 300-900 A.D. onboard double-hulled voyaging canoes that traveled over 2,000 miles across the largest ocean on the planet, navigating by the stars, currents and winds. This is a feat often regarded as one of mankind’s most amazing achievements. These exceptional watermen brought their traditional knowledge of fishing, farming, healing, carving, weaving and other skills necessary to establish themselves in this new land, along with their staple crops, seeds and animals to feed and sustain new and growing communities.

Upon arriving on the islands, they discovered a lush landscape with rich soil nourished by rain and volcanic ash, abundant sea life and clean trade winds, which made the archipelago ideal for settlement. Over many generations of back-and-forth voyages, the population of Hawaii grew, and through innovative agricultural and aquacultural techniques, these early Hawaiians established highly productive and sustainable food systems that easily fed the inhabitants. The phrase “He ali‘i ka ‘āina, he kauwā ke kanaka,” which translates as “the land is chief, and mankind are its servants,” sums up Hawaiians’ respect for and honor of the land and sea as supreme life-giving forces and the importance of environmental stewardship within the culture.

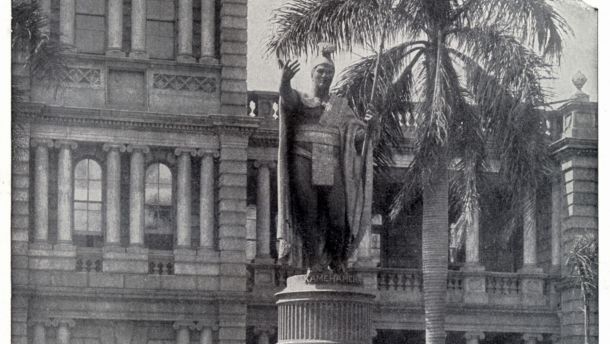

Who was King Kamehameha?

Social systems established on each island were ruled by a royal class of ali‘i (chiefs), but eventually battles among rival leaders erupted, changing the future of these separate island chiefdoms forever. Kamehameha was a Hawaii Island chief prophesied to one day rule the entire archipelago. After unifying the island of Hawaii in 1795, he took his forces to the neighboring islands in a campaign to unite them all under Hawaii’s rule. By 1810, he had consolidated them, becoming the Mō‘ī (Supreme Ruler) of Ko Hawai‘i Pae ‘Āina, the Kingdom of Hawaii. The island chain became known as the Hawaiian Islands because Kamehameha—a Hawaii Island chief—had won the wars.

King Kamehameha II and missionary influence

In 1819, Kamehameha died, and his son Liholiho was proclaimed Kamehameha II. Heavily influenced by his stepmother and Queen Regent Ka‘ahumanu who had embraced Christianity, he abolished the Kapu—a strict set of spiritual laws that governed everyday life—and had many traditional religious sites destroyed. The missionaries were critical of all things Hawaiian, believing the people and culture were barbaric and hedonistic. They found the native preference for surfing over church objectionable and began preaching against Hawaiian customs and beliefs. Kamehameha II recognized the value of the missionaries’ tradition of literacy and adopted it, helping create the alphabet for a people whose language and history had only been transmitted orally for generations. In 1824, King Kamehameha II traveled to England to meet with King George IV in an effort to strengthen Hawaii’s ties with Britain and attain recognition of Hawaii as a nation state. During the trip, the Hawaiian ruler and his delegation were entertained by the Foreign Office as royal guests at the opera and theater, but the two monarchs never got a chance to meet because Kamehameha II and his wife Queen Kamāmalu contracted measles and died in London on July 14, 1824.

King Kamehameha III and Hawaii’s kingdom recognition around the world

Following Kamehameha II’s death, his brother Kauikeaouli was named Kamehameha III. Building on his older brother and father’s work, he launched a nationwide literacy campaign that would transform a nation with a nearly zero percent literacy rate in 1820 into one of the most literate nations in the world, with a 91-95% literacy rate in just 14 years. Kamehameha III continued working to gain international recognition of Hawaii as a nation state. Nineteen years after assuming power, Kamehameha III’s envoys, including Timoteo Ha‘alilio, secured the recognition of Hawaii’s independence by Great Britain and France with the signing of the Anglo-French proclamation on November 28th, 1843, making the Hawaiian Kingdom the first non-European nation welcomed into the Family.

Over the next 50 years, through Kamehameha III’s death and the reigns of successors Kamehameha IV and Kamehameha V, the Hawaiian Kingdom signed treaties with major world nations and established over 90 legations and consulates around the world. The Hawaiian Kingdom became one of the most progressive nations in the world during the Hawaiian Monarchy.

King Kalākaua and the first Hawaiian renaissance

In 1874, following Kamehameha V’s death, Kalākaua was voted as the next King of Hawaii. King Kalākaua was of chiefly descent, closely related to the Kamehameha line. An avid enthusiast of innovation and technology, he sought to strengthen the Hawaiian Kingdom’s relationships and status as a member of the Family of Nations. He was the first foreign leader ever to be welcomed at the White House for a State Dinner in December 1874. Much like his voyaging ancestors, King Kalākaua embarked on a journey to circumnavigate the globe in 1881, becoming the first head of state to do so. Besides building stronger diplomatic ties with other countries, he was seeking knowledge and resources that could be brought back to the Kingdom. During this trip he attended the International Exposition of Electricity in Paris and later met Thomas Edison in New York who convinced him that electricity was superior to gas for lighting. King Kalākaua was so taken with the technology that he had electric light bulbs installed at ‘Iolani Palace in 1886, more than five years before the White House. Honolulu’s streets got electric lighting less than two years later, and by 1890 approximately 800 private residences had electricity, well before other nations.

King Kalākaua‘s motto was “Ho‘oulu Lāhui“—to promote all things Hawaiian and grow the nation of Hawaii by reinvigorating cultural practices such as Hula (Hawaiian dance), Mele (music), Lā’aulapa‘au (traditional healing), Mo‘okū’auhau (genealogy) and Mo‘olelo (traditional stories). The King’s growing popularity and promotion of language and culture antagonized the Reform Party (also known as the Missionary Party), which had successfully eradicated these practices. The missionary descendants had become influential in the islands’ business affairs and sought to regain control, forming the Hawaiian League, an armed group with the aim of protecting settlers’ business interests in the belief that the “native was unfit for government and his power must be curtailed.”

What was the Bayonet Constitution?

In 1887, with King Kalākaua’s popularity at its peak, the Reform Party staged a violent takeover of the Kingdom’s government. With the support of the Honolulu Rifles, the Hawaiian League forced King Kalākaua to sign a new constitution under duress. Later known as the Bayonet Constitution because of the use of force involved, it diverted power from the King to the missionary-controlled cabinet and attached land ownership and income requirements to voting rights. It also restricted voting eligibility to Hawaiian, American or European men who had been residents for a minimum of three years. This watershed moment shifted voting and political power away from Native Hawaiians who were generally not landowners, and into the hands of the American, British and German business parties in Hawaii.

The Bayonet Constitution also put an end to the Kingdom-sponsored Education of Hawaiian Youths Abroad program that Kalākaua had launched in 1880 to provide students with educational opportunities beyond those available in Hawaii. Through this initiative, students had attended institutions in Italy, England, Scotland, China, Japan and California, but were now recalled or left to find their way back to the islands on their own. King Kalākaua died from chronic health problems while visiting San Francisco, California on January 20, 1891 and was succeeded by his sister Lili‘uokalani. He is remembered as the architect of the first Hawaiian Renaissance for his efforts to reinvigorate Hawaiian traditions. At the time of his death, the population of Native Hawaiians, which was estimated to be more than 800,000 in 1778 when English explorer Captain James Cook arrived in the islands, had dropped to 40,000 due to the introduction of foreign diseases of which the Hawaiian people had no immunity.

Queen Lili’uokalani and the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom

When Queen Lili‘uokalani ascended to the throne in 1891, she toured the Hawaiian Islands and learned that an overwhelming number of her subjects were distraught over the Bayonet Constitution which had stripped Native tenants of their voting rights. In response, she moved to draft a new constitution. Alarmed by this development, the Committee of Safety, a group of wealthy businessmen worried about the possible impact on their interests, overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom’s government with U.S. Navy support on January 17, 1893, forcing Queen Lili‘uokalani to abdicate. She did so under written protest to the United States, assuming that following an investigation into this act of war, the United States would restore her as constitutional monarch of Hawaii. Her restoration was never enacted. The overthrow ushered in an era of prolonged confusion regarding the Hawaiian Kingdom’s political status and marked the beginning of the denationalization of Hawaii.

The annexation of Hawaii and the suppression of language and culture

The Committee of Safety quickly proclaimed themselves the Provisional Government of Hawaii and its rightful leaders. Intent on strengthening the Provisional Government’s hold on the Kingdom, they declared themselves the Republic of Hawaii in 1894, naming Sanford B. Dole as president. Three years later, the Republic of Hawaii sent envoys to Washington D.C. to lobby for annexation to the United States. The Hawaiian community responded by initiating a signature drive opposing the attempt. The Hui Aloha ‘Āina (Hawaiian Patriotic League) and the Hui Aloha ‘Āina Wahine gathered more than 21,000 signatures on the “Kū‘ē Petition—The Petition Against Annexation.” Presented to the United States Congress by Queen Lili‘uokalani and the delegates of the Hui Aloha ‘Āina, the Kū’ē petition demonstrated the overwhelming opposition to annexation by the people of Hawaii. Congress failed to reach the required two-thirds majority vote and the annexation treaty was defeated. Hawaii was eventually made a U.S. territory in 1898 and the fiftieth state on August 21, 1959.

In 1896, the Republic of Hawaii banned instruction in Hawaiian within the public schools and many Hawaiian children were physically and emotionally punished for speaking it in school. The language would not be heard in a classroom again for the next four generations. A decade later, the Hawaii Department of Education created the “Programme for Patriotic Exercises in the Public Schools.”

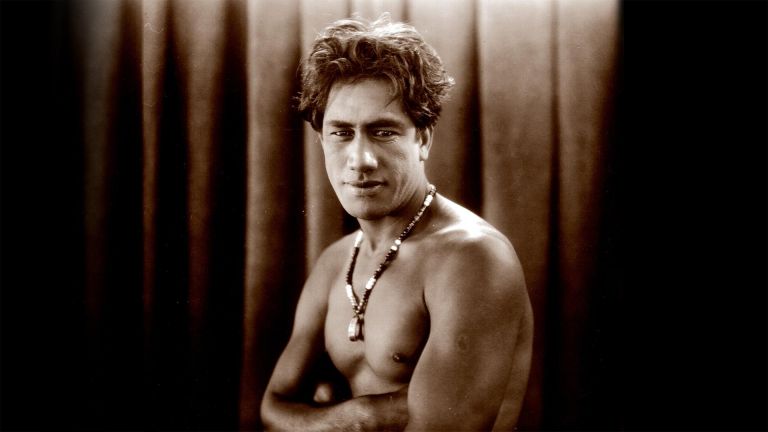

Duke Kahanamoku and the second Hawaiian Renaissance

Duke Kahanamoku was only three years old when Queen Lili‘uokalani was deposed and the Kingdom was overthrown. As a young boy in school, he was taught exclusively in English and reprimanded when speaking his mother tongue. He would reclaim his Hawaiian identity in the water by surfing, swimming, fishing and diving like his ancestors before him. By the early 1900s, Duke Kahanamoku’s success on the world stage turned him into a local hero. He was someone Native Hawaiians could look up to, admire and see themselves in—his achievements evidence of their forefathers’ abilities and the value of their way of life—sparking a revival of Hawaiian cultural pride at a time when political powers in Hawaii were actively distancing themselves from the Kingdom’s government and history, native language and customs. But it wasn’t until the 1970s, after more than 80 years of repression of Hawaiian culture, that a movement to recapture what had been lost ignited and became widely known as the Hawaiian Renaissance.

They reclaimed traditional navigation and voyaging knowledge by sailing the canoe Hōkūle‘a from Hawaii to Tahiti without the use of modern instruments, disproving theories that Polynesians had simply drifted aimlessly until they reached land (Walker, 2011, page 116). As a community, they demanded their right to access Hawaiian language in schools and that it be made an official language of the State. Collectively, these efforts helped instill a sense of Hawaiian cultural pride, Hawaiian language revitalization and advocacy for the protection of the ‘Āina (land). Hawaiian historian and author George Kanahele gave a speech to the Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs in 1977, helping coin the phrase “Hawaiian Renaissance.” For Kanahele, this rebirth of the Hawaiian language and culture “reversed years of cultural decline; it has created a new kind of Hawaiian consciousness; it has inspired greater pride in being Hawaiian; it has led to bold and imaginative ways of reassessing our identity; it has led to political awareness; and it has had and will continue to have a positive impact on the economic and social uplifting of the Hawaiian community” (Walker, 2011, page 10).