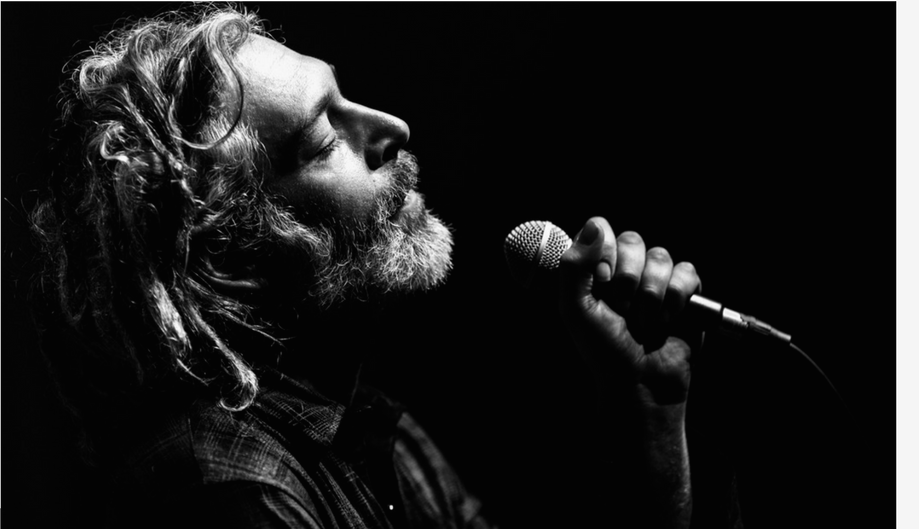

When he first started performing in 2004, Matthew Paul Miller says his approach to the music industry was embracing “a religious, rebellious punk rock attitude.”

Six years later, when he released his debut album, Shake Off the Dust… Arise, it was clear that Miller, better known as Matisyahu, was taking that philosophy to heart: he was refusing to perform on Friday nights, to stay in fancy hotels and also to shake women’s hands—all in the name of his orthodox Hasidic Jewish lifestyle.

True to his ideals, his music reflected his beliefs: he frequently touched on themes in Judaism combined with a unique spin on reggae, rap and hip-hop. Over the course of his five albums and more than 10-year career, Matisyahu did not perform or collaborate with a woman.

One aspect of Orthodox Judaism prohibits a woman from singing in front of men, that a woman’s singing voice is a sexual temptation, and while this aspect of his faith never really sat well with him, Matisyahu’s experience with religion was all-or-nothing, he says. When Shakira attended one of his shows and offered him an opportunity to open for her on a world tour, he turned the gig down. When he saw female performers within his community struggle between pursuing their dreams and remaining faithful to their religion and family, he was torn.

That feeling of conflict continued to build until a few years ago when he finally decided that this was one rule worth breaking.

In 2016, Matisyahu collaborated with New York-via-Columbia electro-pop duo Salt Cathedral on two songs, his first time working on music with a woman.

“I started to trust my own intuition again after spending a lot of time really going beyond myself and out of myself,” Matisyahu said. “I was like, ‘Hey, this is really not godly at all. I can’t see how this could be something that could be commanded by God and the God that I know and relate to.’ ”

The results of those sessions produced, “Unraveling,” the lead single from Salt Cathedral’s upcoming 2017 debut full length, Big Waves/Small Waves, and “Carry Me,” from Matisyahu’s 2016 EP Release The Bound. Despite not collaborating with a woman on music before, the writing process for both songs was surprisingly organic, Matisyahu said. The duo played him “Unraveling” and he got writing, penning his verse, and then the chorus, which he thought would suit vocalist Juliana Ronderos’ voice.

“That’s the first time I’ve written and have someone else sing the part that I wrote,” he said. “That was a cool experience for me, that was kind of unfamiliar.”

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/290401863″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

While Matisyahu sees his change in perspective as the ushering in of a new phase of his career, there are plenty of other musicians who have experienced both religious and professional enlightenment from merging their faith with their art.

For the better part of a decade, Miriam Sandler was traveling the world, attending parties with the rich and famous and lending her vocals to the likes of Gloria Estefan, Julio Iglesias and Michael McDonald as a backup singer both live and on recording. Her debut album The Solution, featured writers and producers that worked with Estefan, Ricky Martin and Jennifer Lopez.

It was a life she describes as both glamorous and toxic. She had reached the peak in her career and was wondering if there was something more out there for her. Following her sister’s lead, Sandler connected to her Jewish faith, a denomination she grew up identifying with, but didn’t practice dedicatedly. Her father’s subsequent pancreatic cancer diagnosis helped bring her closer to him and eventually the orthodox lifestyle she now lives.

Because of this, Sandler only performs for audiences of women and girls. For the same reasons Matisyahu turned down opportunities to collaborate with women, Sandler chose not to sing in front of men. She found it a transformative experience, one that made her feel safe, welcome and not in competition with other women.

“I realized after performing for female-only audiences that this was the reason I had a voice,” Sandler said. “I’ve been doing this for close to 17, 18 years. I’ll never go back to performing in front of men. I feel like a completely different person.”

While Sandler and Matisyahu have experienced different shifts in their careers, both are in agreement that their choices when it comes to their faith haven’t hindered their opportunities.

“In your career, you piss off a lot of people, that’s a part of what happens,” Matisyahu said. “I don’t think a person’s career is based on who they piss off or who they don’t.”

Orthodox Jewish artists are hardly the only musicians altering their career paths due to religion.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4O_yq2P6Oes&w=560&h=315]

Cat/Yusuf Stevens famously converted to Islam, sold his guitars and embarked on a charitable path—without music—for nearly 30 years. While all music, in the broadest sense of the word, is not prohibited by Islam, music with content that includes swearing, mentions of sexual activity, or consumed for entertainment purposes is forbidden. In order to avoid confusion, Stevens opted to stay away from music altogether until he saw one of his son’s guitars laying around the house in the early 2000s.

“I picked it up and my fingers knew exactly where to go,” Stevens said in a 2006 interview with Billboard. “I’d written some words and when I put them to music, it moved me and I realized I could have another job to do.”

Beginning with his 2006 album An Other Cup, his first recorded work since 1978, Stevens gave the music industry another go without regrets in regards to his time away from the spotlight.

Throughout her childhood in Amsterdam, Moroccan-born singer and performing artist Rajae El Mouhandiz faced navigating two religious realities: the Christian teachings in school and the Islamic teachings at home.

“From a very young age I unwillingly became an expert in inter-religious dialogue and intercultural dialogue because I grew up with grown ups all defending their big faiths and telling me what ‘the truth’ is and trying to sell me ‘the truth,’” El Mouhandiz said.

The arts, she found, didn’t rely on truths and faiths, but rather your discipline and dedication to practicing and performing. So at 15, El Mouhandiz left home and studied music at a Dutch conservatory where the rules were about hitting the right notes and not whether you’re a Muslim woman.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYMEYAUNkYs&w=560&h=315]

The intersection of El Mouhandiz’s background and music career created friction when both Western and Muslim labels were unsure of how to market her. She didn’t want to give into a sexualized image, popular with Western musicians, however she wasn’t satisfied with remaining behind-the-scenes as a songwriter for their male artists. So she started her own label, Truthseeker Records.

“I was able to say, ‘I’m going to go and create my own little island, I’m going to start my own label,’ ” she recalled. “I don’t care what the Western world says with their boxes or the Muslim world with their patriarchal label because in the arts it’s still not done for a woman to be a performing artist and be in dialogue with the whole world. That’s the biggest lesson [my mentors] have taught me: don’t be sad you were born in all these weird boxes, maybe that’s your blessing, maybe that’s the story you’re going to tell.”

Faith is a defining characteristic for many people, regardless of their profession. Despite strong beliefs many artists continue to create secular music or lyrics with allegories without overt religious overtones.

On her 2015 debut, Julien Baker confronts God, most notably on “Rejoice,” a song that details an omnipresent divinity. “But I think there’s a god and he hears either way / when I rejoice and complain,” she sings. Baker grew up Christian, but found a stronger sense of faith when she came to terms with her sexuality and how God is accepting of her.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lYIiHZCcZpw&w=560&h=315]

“I believe there’s a God that’s listening, but I think that we owe it to ourselves as people who believe in love and compassion to do more than a trite ‘God is listening,’ ” Baker said in an interview with the Observer.

Similarly, Sufjan Stevens, also a Christian, manages to create a more inclusive sonic narrative rather than one that “alienates listeners of different beliefs,” the Atlantic points out. His 2004 album Seven Swans touches on many Biblical allegories like the story of Abraham.

With both Baker, Stevens, Matisyahu and many others, their faith has not proved a hindrance to their collaborative abilities or their marketability. In fact, the extension of their beliefs into their music isn’t just an aesthetic choice at this point—it’s a become a defining characteristic of their music that’s driven them to levels of creativity they might never have reached had they not dared to tap into the struggle between their faith and ambition as a source of divine inspiration.

“I still describe myself as a Christian, and my love of God and my relationship with God is fundamental, but its manifestations in my life and the practices of it are constantly changing. I find incredible freedom in my faith,” Stevens said in an interview with Pitchfork.

But for El Mouhandiz, finding freedom outside religious doctrines, while still respecting her own heritage—she was the artistic director and producer for a Dutch version of the American production of Hijabi Monologues—and the faiths of others has helped her offer different, unique perspectives and share stories from all over the world, including the Muslim and Christian worlds she balanced in her youth.

“It’s still not done for a good [Muslim] girl to be a performer, it’s still frowned upon,” she said. “If she’s famous of course they’ll love her when she’s on the TV singing love songs, but she shouldn’t have her own opinion, she shouldn’t be commenting on religion, she shouldn’t be commenting on relationships or society. If any group should, it should be religious women whether they’re Muslim or Christian or Jewish, they should take artistic spaces to talk about who they are.”