In a tea room just outside Bangladesh’s Rohingya refugee camps, a group of young activists fiddle with their phones, which have suddenly started pinging in chorus now they are finally reconnected to the internet.

To circumvent a government internet blackout around the camps in Cox’s Bazar, they have to break a ban on travelling to nearby Bangladeshi towns, from where they can communicate and coordinate messages for the international community.

With simple smartphones the activists have been able to build some kind of Rohingya voice, speaking to the world through WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter. But their efforts have often been frustrated, mostly for a more fundamental reason than the technological barrier in place since August: they believe the aid community sent to help them is not listening.

“The Rohingya community are not weak, but the situation makes us weak,” says Mohammad Arfaat, an activist who was part of a Rohingya team that made a short film about how violence had forced them from Myanmar in 2017.

He has been calling for more help for Rohingya to launch their own initiatives, for everything from education to arts, but complains there has been no support. “The Rohingya youth are very talented … but nobody sits, nobody talks with them, so their voices have stopped,” says Arfaat.

These concerns have risen since August, when Bangladesh responded to a failed attempt to repatriate the Rohingya – for which not a single refugee volunteered – by imposing tighter restrictions on their movement and communication.

Arfaat says that, despite the crackdown, UN agencies and international aid groups have not been present.

“No one comes to research what’s happening. [They] have protection officers, but what are they protecting? Whenever there’s violence, they’re not here,” he says. “You see them on social media, talking to the public, but they don’t come to talk to us.”

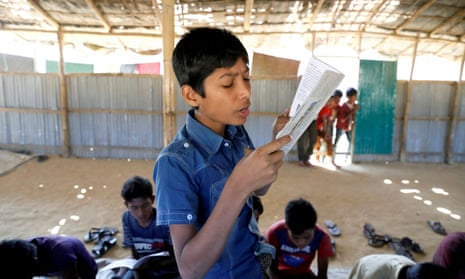

Lack of education has been a particularly pressing concern among Rohingya activists, who have campaigned for years against a government ban on all but the most basic level of schooling, warning of a “lost generation”.

They won a victory last month when Bangladesh announced a pilot programme to teach children between 11 and 13 the Myanmar curriculum. Rohingya teachers and activists had little knowledge of how the plan would work, however.

The restrictions have been in place since the existing camps were established in 1991, when the same fears about future generations prompted Rohingya who had been educated in Myanmar to set up their own independent learning centres in secret, funded by small monthly contributions from parents.

Similar models have become more prevalent since 2017, when the Kutupalong refugee camp became the world’s largest as it absorbed the hundreds of thousands of people who fled a Myanmar military operation described by the UN as having “genocidal intent”.

Activist Khin Maung says that despite three decades of Rohingya experience in the refugee camps, their expertise is not tapped by humanitarian workers.

“They don’t have the interest to develop our children, they just have the interest to implement their [own] projects,” says Maung, who heads the Rohingya Youth Association. “They are ignoring us because we are refugees. If they treated us as human beings, they would listen to us.”

He complains that organisations implementing education projects often employ underqualified tutors who teach only basic phrases and nursery rhymes, failing to utilise the talents of refugees.

A 2019 study by the Peace Research Institute Oslo said that, despite the barriers imposed on the humanitarian community by the government’s education ban, more could have been done to map out the work carried out by Rohingya themselves.

“The humanitarian sector often falls short on centring community voices in this way, which I think is due in part to policy restrictions, limited resources and a lack of flexibility,” says the report’s co-author Jessica Olney.

“It’s also due to quick staff turnaround, as many humanitarian staff are new to the Rohingya community and aren’t encouraged or permitted by their agencies to spend time in the camps just talking to people and listening to gain a deep understanding of the context and people’s needs.”

The relationship between the Rohingya and the humanitarian community has been strained by a recent government order to stop paying refugee volunteers in cash, which the authorities claim is used to buy false documents. The government has encouraged the hiring of Bangladeshis instead.

Refugees claim they have been removed from volunteer roles, which typically pay a daily stipend of less than £3, which forces them to rely solely on the aid supply of oil, lentils and rice.

NGOs operating in the area claim “miscommunication” was a reason some Rohingya had been dismissed.

“There is a major communication breakdown between some international humanitarian organisations and the Rohingya refugee volunteers about why they are being dismissed,” says John Quinley, human rights specialist for the advocacy group Fortify Rights, which has documented the dismissals.

There was a similar outcry by refugees when the UN refugee agency, the UNHCR, signed an agreement with Myanmar on repatriating the Rohingya in 2018. Refugees said they were not consulted on that deal, or about a system for biometric registration.

A spokesperson for the UNHCR says the agency used several methods to share information with refugees and engage community leaders, including face-to-face meetings, drama performances and podcasts.

The spokesperson adds: “The Rohingya refugee population in Cox’s Bazar is more than 850,000 people. This alone presents a challenge in terms of ensuring that all voices are heard. Furthermore, to communicate effectively with a very large population requires the utilisation of technology. Currently, this presents challenges in Cox’s Bazar due to restrictions on mobile connectivity.

“UNHCR works to ensure that refugees are consulted on key issues and are involved in decision-making processes including through regular protection monitoring and profiling, as well as community outreach. Refugees should be consulted on all issues related to their daily lives and not only significant political developments.”

Maung says the role played by refugees in the humanitarian response over the past two years, from volunteering as translators to other key roles, has been underestimated.

“They ignore us but without Rohingya involvement they can’t do anything in the camps, they can’t even understand us properly. They don’t know our language,” he says. “We are the nuts and bolts.”