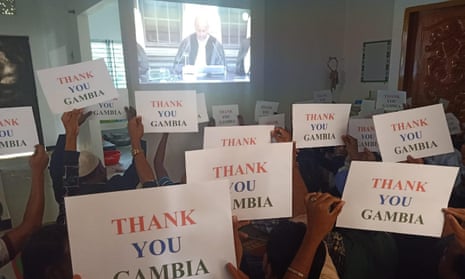

On Thursday the internet in Kutupalong, a city-sized refugee camp in south-eastern Bangladesh, was switched back on for a few hours. The camp’s residents gathered around their phones as, 5,000 miles away in The Hague, the international court of justice (ICJ) delivered a ruling on Myanmar’s treatment of its Rohingya Muslim minority. They cheered as the court issued a set of legally binding obligations: that Myanmar’s military does not commit acts of genocide against some 600,000 Rohingya who still live in the country, and that evidence of past crimes remains intact.

This was the first legal victory for Rohingya since 2017, when upwards of 700,000 were driven into Bangladesh in a campaign by Myanmar’s military that produced the most concentrated outflow of refugees anywhere since the Rwanda genocide in 1994. Responding to attacks by Rohingya militants on security posts in Myanmar’s Rakhine state in late August 2017, military units acted with such ferocity that, within two months, the country had been emptied of nearly half its entire Rohingya population. Those who made it to Bangladesh recounted how troops encircled villages at night and opened fire, cutting down those who fled. Satellite imagery revealed more than 380 destroyed villages, and in the year that followed, new security bases were built where Rohingya homes once stood. Yet until now, there had been little substantive international action.

Aung San Suu Kyi has dismissed the credibility of the case, which was brought to the ICJ by the Gambia. In December, she travelled to The Hague to defend the military, and in an piece for the Financial Times yesterday, she wrote that the ICJ has been “precariously dependent on statements by refugees” in Bangladesh who “may have provided inaccurate or exaggerated information”. She insisted there have been efforts to bring “stability and progress” to the region where the violence took place, but that they have been hindered by international condemnation.

In that corner of Myanmar, remaining Rohingya are confined to camps, ghettoes and villages – as they have been for seven years – and face arrest if they leave without permission. The tide of public antipathy is overwhelming, and Aung San Suu Kyi’s line echoes a popular view inside Myanmar of Rohingya as scheming and deceitful. Soon after the exodus began in 2017, government spokesperson U Zaw Htay told media that the flight of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya was part of a “plot” to mislead the international community.

For those in Myanmar who see deceit in everything Rohingya say, any investigation that draws on their testimony is illegitimate. But there is also no appetite for on-the-ground investigations: a UN fact-finding mission has been repeatedly denied visas. Mass demonstrations in support of the military’s campaign, and of Aung San Suu Kyi’s recent defence at The Hague, show that derision of Rohingya cuts across longstanding political divisions in Myanmar.

Unsurprisingly, Aung San Suu Kyi’s government was quick to reject yesterday’s ruling, stating that whatever occurred in 2017 was being investigated internally. This is unconvincing. When journalists working for Reuters produced evidence in 2018 that 10 Rohingya had been executed, seven soldiers were jailed. Less than a year later, they were quietly released.

The kind of language used by government officials provides further evidence of just how precarious the situation is for those who remain. Their supposed deviousness – spoken of as a collective trait, common to all Rohingya – has provided the basis for the violence of recent years to take on its collective dimension. That shift from individual to group produces the mental state in which genocide becomes possible, and the ICJ’s decision should be read as a warning that once that state has been established, the threat of recurrent violence is high.

The ruling, which requires that Myanmar produce periodic reports detailing the protective measures it is now obliged to enforce, ensures that whatever the military does from now on will remain under the close scrutiny of the court. But while violation of the Genocide Convention could, and certainly should, invite serious criminal charges against perpetrators, that remains subject to political will – the ICJ has no jurisdiction over individuals, so it cannot bring those charges itself. The likelihood that the architects of the genocide – chief among them Min Aung Hlaing, head of Myanmar’s military – will face trial is slim. International law has yet to devise effective mechanisms to bring actors protected on the UN Security Council by powerful countries – in Myanmar’s case, China – before a judge.

Until that changes, states that seek to drive populations beyond their borders, whether in response to a perceived threat or for political capital, or both, can continue to do so. The ICJ ruling is a bright point in an otherwise woeful international response to the internment of Rohingya and the organised violence against them – a process that began long before the violence of 2017 – but its powers are limited.

As the international legal expert Priya Pillai notes, the ICJ twice ordered provisional measures during the Bosnian war, yet this did little to stop the Srebrenica genocide. Rohingya will become yet another test case for how international law protects vulnerable minorities, but they won’t be the last.