7 Strange Days

With The Young Men of The Syrian Resistance

Words and photographs by Danny Gold

In late March in a safe house in the embattled Syrian city of Ras Al Ayn, where a fragile cease-fire stands between warring rebel factions, Yilmaz is doing his best to convince me that Mossab actually prefers to sleep with men. Mossab, to the left of me, is not amused. As the perpetual brunt of jokes in the brigade, he can only shake his head and sigh. Fahd is, as usual, on the phone with one of his girlfriends, his hand still bandaged from the sniper bullet that tore through it a while ago. Later that evening I will inquire and learn that his standards are quite low. I will also learn the Arabic word for spastic or disfigured, I can't tell which. Chava, the sixteen-year-old they call "the mad one" because of how recklessly he behaves in battle, is poking around Facebook on his tablet. Someone is on his cell, trying to score some hash. The one everyone calls "the Iraqi" is playing music on his phone, alternating between sad songs about Iraq and Mariah Carey ballads. Usama Hilali, the stone-faced commander with a bounty on his head, is in the corner, grim but chuckling every so often.

"You believe these guys are fighters?" Abu Islam, the thirty-year-old financial advisor turned sniper, asks me with a smirk.

Syria is a place of misery. One of leveled cities, starving children, the dead and the wounded, destroyed families. But while the leaders make deals, shift and break alliances, the young men bear the brunt of the battle. They fight and they lose friends and they worry about the family they haven't seen in eight months and they kill. Even those who had never touched a weapon and bear no sectarian grudges grow less and less compassionate on a daily basis. You can see it in their eyes as they mainline videos and photos uploaded to the Internet of people like them, people from the same city or born into the same group, killed or beaten or tortured beyond recognition. And you can see the anger rise and the willingness to do the same or worse to the perpetrators build. It is easy to imagine that day after day after day of this, martyrs and shaheeds and scars and torture and bloodied children, propaganda or otherwise, you'd be hard-pressed to let thoughts of mercy into your mind.

And yet these are still young men. And though they are caught up in one of the most brutal wars in recent memory, with no end in sight, they behave like young men. Talking women, talking shit, busting balls. When this war ends, if it ends, however it ends, these are the young men who will have to be persuaded to put down their guns. For some, the revolution is the first time they've ever picked one up. For a small few, it's another battle along ethnic or sectarian lines, like those fought in Lebanon or Iraq. The Iraqi even claims he killed some Americans in Fallujah. But we'll get to that later. What's important right now is that I learn the correct Arabic pronunciation of the phrase "Fuck your mother's pussy."

It's past midnight, and we're sitting in one of four rooms in a single-story house that's become a base of sorts for the Mashaal Tammo brigade—a mixed Kurd and Arab group of fighters from Hasakah province that takes its name from a prominent Kurdish politician and activist murdered during the beginning stages of the revolution. The brigade first formed through networks of activists. Some had known each other for years, while others met through the peaceful stage of the revolution or through the Internet. Some only recently joined.

Roughly ten or so fighters sleep here at one time, ranging from sixteen to thirty-six. Charging laptops, phones, tablets, and walkie-talkies are sprinkled across the floor. Electricity is scarce in Ras Al Ayn, and power is only on for an hour or so every few days. This house, however, has a generator running most of the time.

Camouflage pants hang here, a couple of guns are strewn about over there. Ashtrays and cigarettes are everywhere. A hookah, used often, sits in the corner. At first, the guys claim they took the house from a shabiha, one of the irregular fighters supporting the Assad regime. A few days later I'm told the house was given to them. Then I'm told the man who owns the house is actually the brother of ashabiha, and he fled to Aleppo.

The men spend most of their time gathered in one of the rooms, sitting, smoking, making phone calls, texting. This is the downtime of the war. They stay up until five or six in the morning, smoking and talking shit with each other, then sleep late. There's little to do, and some are itching to get back to the battle. Sometimes someone will go off to another village, sometimes there will be a protection run. But for now, the fighting has stopped. This means sitting around the house, awaiting orders, killing time. Friends stop by and visit, siblings for those who live close by. TV is watched; social media is consumed.

The man who brought me here is a Syrian Kurd named Yilmaz. He was born and raised in Ras Al Ayn, a city of about fifty thousand people on the Turkish border. It's a diverse mixture of Kurds, Arabs, Christians, Armenians, and Chechens in Hasakah province, where the majority of Kurds are concentrated. Kurds make up about 10 percent of Syria's population, and were notoriously repressed by the Assad regime.

The early-twenties Yilmaz is a member of what he calls the "activist media." Essentially, that means he tags along with the Free Syrian Army, uploading videos and releasing statements. Like many of the fighters, he started off as an enthusiastic participant in the peaceful revolution, leading demonstrations and desecrating public images of Assad. He remains personally nonviolent —though during one drive around town, he proudly points out a poster of Assad he shot up with a paintball gun.

When the revolution started, the main Kurdish political party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), tried to avoid aligning with any of the different sides. While they despised the regime, they also did not trust the Sunni Arab rebels leading the Free Syrian Army (FSA), whom they felt had not assured them Kurdish rights would be respected in a new system. The PYD also had intentions of carving out more autonomy in the Kurdish majority areas in Syria, much as the Kurds in Iraq had done after Saddam Hussein's fall.

The PYD gave birth to the People's Protection Units (YPG), the most powerful Kurdish militia. Not all Kurds, however, support the PYD and YPG. Affiliated with the Turkish Kurdish insurrection movement known as the Kurdistan Workers Party, the PYD and YPG are seen by some as being too authoritarian. Accusations have flown about the PYD using all manners of repression against Kurds who don't toe their party line, especially those who wanted to start fighting the regime right away.

It's these incidents that pushed some Kurds, like Yilmaz, into joining up with the overwhelmingly Sunni Arab Free Syrian Army, under whose aegis the Mashaal Tammo brigade falls. For the majority of Kurds, though, the YPG is the only armed group they trust to protect them.

Everywhere we go in the city, there are bullet holes, rubble, burn marks. The hospitals and the schools, many the scenes of pitched battles, have all been shut down. Down the street from the safe house, the Al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat Al Nusra has set up shop. Across town, the YPG has a sizable force patrolling the streets. Despite the cease-fire, if some of the FSA fighters in the safe house cross over into YPG areas of town, they'll likely be shot or taken prisoner.

Some, like Usama Hilali, are rumored to have heavy prices on their heads.

Hilali started the Mashaal Tammo brigade in the city of Qamishli, regarded as the capital of Kurdish Syria. Good-looking, stocky, with a perpetual five o'clock shadow and a beanie, he carries himself with a more serious air than many of the others.

He's reluctant to talk at first, and answers questions with only two or three words. He's found mostly in the corner of a room, laptop in hand, watching online videos of battles, checking the Facebook pages of various rebel groups.

Facebook is huge among the Syrian fighters. They are friends with different groups and commanders, are constantly uploading photos and communicating with each other. They post updates from battle preparations, and photos of themselves with their fellow soldiers, holding their weapons or rebel flags. They constantly share videos and photos of the dead as well.

Hilali says he was one of the first peaceful protesters, like Yilmaz, leading the revolution. His father's shop was located near the main mosque in Qamishli where the protesters and activists organized. Hilali started to supply them with food, water, and paint, to plan with them, to help. He says the YPG didn't like that. He was imprisoned. After he was released, he decided to form his own armed brigade, and at that time the YPG were the only ones with guns. They didn't like him picking them up. The FSA, on the other hand, supported him.

Rumors circulated online that he was fighting with the Islamists—teaming up with the Arabs against his own people. His family is constantly watched, he says. The shop he runs with his father has been firebombed.

He's also wanted for a murder—which he admits he committed—prior to the revolution. His sister and her husband were having issues. Hilali went to mediate. Six men attacked him, and he fought back, killing one. If the rebels prevail, he will have won liberty for his people, but lost his freedom. "If I survive the revolution, I will turn myself in," he told the website KurdWatch.

He shows me pictures of his children. In some, they are holding guns. He smiles. He's proud of his children. He's more proud, though, of the videos he shows me of the aid organization he worked with during the peaceful revolution, doling out food to internally displaced people in Homs. "The peaceful revolution was more beautiful," he says.

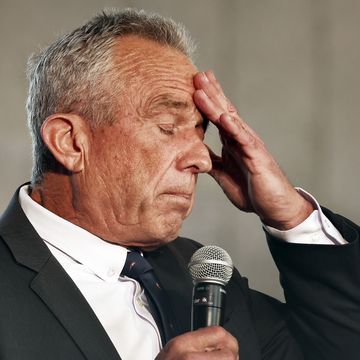

Chava (pictured above) is "the mad one." He's sixteen, also from Qamishli. He was a singer during the peaceful revolution, singing songs about ridding Syria of Assad, attending demonstrations. He was detained a number of times as well. Eventually he picked up a gun. Now he rarely puts it down, even when there's no fighting anywhere remotely close by.

He started fighting at fifteen after being taken prisoner by the YPG. He had gotten to know Marwan, a commander of a separate Kurdish FSA group, and he followed him. He fought in Idlib, an opposition stronghold that has been bombarded by the regime, and then received a little training. He still has family in Qamishli, though one of his older brothers is off fighting with the FSA.

Chava, like any sixteen-year-old, is habitually antagonizing, talking about how much he loves his gun, how much he loves fighting, how much he loves Islam, how he likes Bin Laden (but also George W. Bush).

I ask Chava whether he gets nervous before fighting, and an older man chimes in, "There is no time to be scared." He is Abu Islam, the brigade's best sniper, much admired and usually the center of attention. He grows very intense when he speaks, but he's also frequently funny and punctuates his jokes with loud eruptions of laughter. When a lanky fighter who occasionally gets physically too close for comfort passes through the room, Abu Islam turns to me and goes, "I do not like this man. He is like a spaghetti," and makes a face of disgust.

Even when he's clearly joking, there's always a hint of seriousness. Like when he asks how much Obama would pay if they pretended to kidnap me.

Abu Islam is an excellent sniper, he says, because he grew up hunting, mostly rabbits. Even before the revolution, he ran afoul of the regime: He worked as a financial advisor to a company run by an Assad family member, and was accused of stealing. He claims he had to flee his own wedding when they came after him.

Like all the young men I met in Syria, Abu Islam's taste in music turns toward eighties and nineties divas. At this moment, Whitney Houston's "I Have Nothing" comes on, and Abu Islam starts talking about how much he loved her, and how sad he was when she died. "Her husband was so bad," he says, listening to "I Have Nothing." "He learned her these things," he says.

The one they call the Iraqi is partial to Mariah Carey, the Backstreet Boys, and sad songs about Iraq. Abu Muhammad is thirty-six, the oldest man living in the house, but he giggles uncontrollably as he purposely gets my name wrong every time, yelling out a variety of white American names before finally sticking with "Edward."

He, like Hilali, has the look of a fighter—stocky, with a shaved head, five o'clock shadow, and thick forearms. He appears menacing. The first time we meet, he's holding a giant, dull knife he says he just used to cut the throat of two shabihas. Later, he'll show me their pictures, grainy shots of two unidentifiable men lying in a field covered in blood, dead, after he shows me photos of his wife and baby.

His father is Iraqi, and his mother is Syrian. When the Americans invaded, he left Syria for Iraq in 2003, only returning in 2007. It was a matter of pride. He needed to defend his father's homeland, he says. Throughout the course of the week, he plays Iraqi songs and videos on his phone for me. These aren't songs of anger or revenge, they're songs of sorrow. The videos show images of bloodied children, men clutching dead babies, old women crying, fire, death, destruction. In a lighter moment, he sings me a song he calls the new Iraqi national anthem. Abu Islam translates it for me afterward. It amounts to the singer basically saying, Fuck this, fuck me, fuck you, fuck your grandmother, fuck your grandfather, that everything in Iraq has gone to hell, so fuck everything, and fuck you.

He fought in Fallujah, with a group called Jeish Muhammad. He proudly tells me he killed six Americans there, including two women. I'm skeptical of the women claim and make a note to look it up when I have a chance. After he returned to Syria, he was arrested by the regime and held in prison for nearly three years. He says he was tortured. He shows me fearsome scars on his chest and sides. He wants revenge, but he also wants more than anything to go back to his wife and kids, who he hasn't seen in over a year. They live in regime-controlled territory in Damascus. He says he Skypes with them as much as possible. "When the war is over, I'll go back to my family. I love my family," he says. He's been fighting off and on for a decade now. He says he didn't come back to Syria for fighting—he came back for a normal life.

Hash is smoked most of the nights. About half the guys partake. Weed is even smoked one night, though it probably wouldn't even qualify as marijuana in California. Abu Islam asks me if I'll mention the hash smoking. He's nervous because one of Assad's main talking points early on was that the resistance is a bunch of drugged-out criminals. "We're not drug addicts, you know," he tells me. After a brief conversation, however, Abu Islam decides he wants the world to know that they smoke hash. "It is not just Allahu Akbar and fighting, you understand?"

The days pass. We're standing in a makeshift graveyard with Yilmaz, located right on the border with Turkey in a weedy field. There are seven or eight graves, and a few unfilled holes, ready for more.

In one of the graves lies Yilmaz's cousin, Faisal, his best friend. It is marked only by cinder blocks. Yilmaz says a prayer for the dead, holding his hands up to his face and speaking quietly to himself. It's the first time he's been back since his cousin was buried a month ago. I ask him if it makes him want to pick up a gun. "No, I'll never pick up a gun. I hate weapons, man," he says. We walk away. When we get to the car, Yilmaz shakes his head. "I've lost so many people, man."

Later, Mossab, another young man in the activist media, tells me how it happened. The brigade was going from house to house in downtown Ras Al Ayn, breaking through walls of ground-level apartments and stores to stay out of the open. "They were thinking to attack in a little street, they thought there were no snipers," he says. It was Fahd, Faisal, him, and a few others. They opened the door to go out, with Faisal at the front. Mossab was last, Fahd was second. As soon as Faisal stepped out completely, bullets rained down. They ran back in. Fahd was shot in the hand and leg. Faisal just put his hand on his cheek, Mossab said, and walked slowly. He then sat on the ground. There was blood on his hand. "I'm shot, guys, I feel it, I'm shot," he kept saying. They picked up his shirt and saw a hole near his heart. He recited a prayer, "I am witness, there is no god but Allah and no messenger but the prophet Muhammad." He said it three times, then the blood came out of his mouth, and he died.

Mossab's eyes glisten as he recounts the story. Most of the young men in the brigade count a handful of close friends dead. But Faisal's death has had the biggest impact. Tribute photos of him are the background pictures for many of the guys' Facebook profiles. Faisal's death is the one that really hurt. And it is the one that the men say they seek revenge for.

We're eating dinner, and the Iraqi announces, "I haven't seen my baby in one year, two months." I point to the guys and ask whether he considers them his family now. "Yes, this is my wife," he says pointing to Mossab. "And this is my baby," he points to Fahd. "He's not a good baby, though. He drinks too much whiskey. I think I'll give him back." Everyone cracks up.

That night, two of the big boss men also drop by the house. Montaser Al Khaled is a former captain in the Syrian regime forces who defected. He is now said to be leading the FSA in Hasakah. He appears with a man who is said to be a rank just below him. This man is also a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. He sports a tough leather jacket over a military uniform, and has an elegant, reddish long beard, with deep hazel eyes. He's one of the most interesting-looking men I've ever seen. He doesn't say much.

A nice meal of stewed chicken is prepared for the high-ranking officers. When they show up, the tone changes. Things are more serious, the young men are deferential. Al Khaled and Hilali huddle in the corner and discuss some things. We start to talk to Al Khaled. When he answers questions about Syria, he is stone-faced, grim. When he talks about his family, he lights up. He talks about his two young sons, how he just wants to go home. He speaks of his anger at Jabhat Al Nusra, and of his confusion as to why America and the West refuse to help the moderate FSA. He says this is why Syrians are turning to the jihadi groups. They have money, guns, ammo, food, while the FSA, with little outside support, struggles to take care of its members.

Then it's our turn to answer questions. What do we think of Jabhat? Why isn't America doing anything? Do we have children? Do we have wives, girlfriends? I tell him an old tale of heartbreak, and he starts to beam. It's the most animated I've seen the men—they can't get enough. He makes sure it is all translated for his fellow officer. He tells me these things work out eventually, and that it is probably for the better, that she probably wasn't worth all the trouble anyway, that I will know when I meet the right woman.

Said, a businessman from a nearby city, stops by. He trades in medical supplies and despite his youth, has done well for himself. He is a financial supporter of the brigade, and has known Abu Islam since before the revolution. He tells me he can get wounded FSA treated in regime hospitals because he knows all the doctors. He changes their names, and sneaks them in. He also sometimes helps treat them when they're injured, including Fahd and his hand, from the attack that killed Faisal.

The Iraqi is playing with his knife again. He politely and nonchalantly informs me he just wants to cut me a bit, giggling, using his index finger and thumb to indicate an inch or two. Then he tells me he'll kill everyone. Then he tells me he was kidding, and that he hasn't killed anyone.

Abu Islam is a bit perturbed that I haven't seem them during battle so far. He insists that for the article, I must get the complete picture. "When we are here, we are cool guys, but when we are fighting, we are bad fucking guys," he says.

The men ask me if I want to go for a ride to visit another group of soldiers stationed on the outskirts of town. We pile into a minivan, them clutching their weapons, and drive recklessly through the darkened streets, blasting Free Syrian Army songs with the windows rolled all the way down, stopping here and there to pass armed checkpoints manned by young men much like them.

We pull up to the outpost where the men of Zaid Bin Harith, a small faction of the large Liwa Allahu Akbar brigade, are staying. It's a former checkpoint for the Assad regime. Out front sits a tank tagged up with graffiti like an old subway car.

Their living conditions are much rougher than those of the others. They live in a small, spartan two-room building that used to be an Assad regime building. Their food is sparse. The entire faction here is from a poor neighborhood near the destroyed city of Deir Ezzour, known as Al Bukamal. It's a major crossing point for insurgents moving back and forth between Syria and Iraq, so much so that U.S. even staged a cross-border attack their in 2008. Many of the fighters in this group knew each other before the revolution began. When the fighting started, they joined together.

We sit in the smaller room and partake in the usual getting-to-know-you icebreakers. We talk about girls, America's role in Syria, the dogs in the Assad regime. One of the fighters bears a striking resemblance to Che Guevara. A few of the men from the different brigades know each other, but for the others, introductions are made and handshakes exchanged. Guns are passed around, examined, their finer points discussed thoroughly.

These men are tougher, more on edge, wilder. A few are crudely tattooed. They are looser with their weapons. They play with grenades. At one point, one of the leaders grows agitated when a friend keeps knocking on the door to get in. He points his handgun through a broken window and fires off a shot. Everyone laughs.

This area has recently been bombed by regime forces, they say, with one strike missing their base by fifty yards. "We're not afraid of anything but the airplanes and the snipers," says Abu Kados, who sports homemade tattoos on his forearms and feet. And the tank? They stole it from near Deir Ezzour and somehow managed to drive it over here, despite having no idea what they were doing.

Later, the Mashaal Tammo soldiers tell me that these guys are irresponsible, "crazy."

Yilmaz asks me if I would like to go to a club. I'm confused. He tells me there's a secret disco close to the border that everyone goes to when there is no fighting. Before he can finish his sentence I tell him we have to go. I hastily pack up my stuff. As soon as I tell him I'm ready to go, he starts cracking up, and so do the others.

I ask him what's so funny. "There's no secret disco, you idiot!" He roars with laughter. "We just tell that to journalists to fuck with them." I unleash some of the profane Arabic phrases I was taught on the first night. The men are beside themselves.

Mossab is cooking in the kitchen. The Iraqi is in the big living room, crouched down in front of a laptop. The photographer took a great shot of him in front of the tank, and he's trying to upload it as his Facebook profile pic, but the Internet is acting janky and he's growing frustrated.

Talk turns to politics. Chava is heavy on conspiracy theories, but so are many of the older guys. The main theory right now is that the U.S., Hezbollah, Israel, China, and Iran are propping up Assad. It's a theory I hear frequently from Syrians, despite it making no logical sense. Abu Islam, generally one of the more sensible people in the house, thinks that maybe there is no alliance between everyone, but that all are working to tear Syria apart, because they fear how powerful a strong, united Syria could be.

At this point, Ziad, another rebel, in his late twenties and clad in a Nike hat and Al Qaeda patch on the sleeve of the military uniform he never takes off, starts getting a bit excited. He starts shouting, "We will liberate Lebanon! Iran! And then the Golan!" Someone yells out from behind him, in a fake enthusiastic, mocking tone, "Yeah, and then we'll free the people of North Korea!" This is met with raucous laughter.

The Iraqi is missing his wife, and his family, and his home. He starts talking.

"This country, I love, but everybody, child, woman, baby die. Die die die. I just want my home."

"I want my wife, I want my babies. This, I hate this. I hate guns. My mother, my house, my work is in Damascus."

"Everybody in my country is sick. Everybody in Syria is sick."

"I like waking up in the morning, going to work, see my baby. I'm big man now, you understand? Thirty-six. No more fighting. Finish."

"Condoleezza Rice," Abu Islam pipes up emphatically. "It's just the face she makes when she is talking. I don't know man, the way she talks…I really want to fuck her. She was very good at her job."

We're back at the base, and some of the guys are already stoned. A few more joints are being rolled. Giggles are spreading contagiously. Abu Islam, as always, is dominating the conversation, flowing back and forth in English and Arabic, holding court with his token intensity. "Susan Rice, I think she looks like Condoleezza. I can fuck her," he says, quizzically, as if he has just come to accept this fact.

When talk turns to Hillary Clinton, he grows even more animated. He's a huge fan of the Clinton family. He says he respects Hillary way too much to ever consider sleeping with her. "I wouldn't fuck her, but she is so classy. She's from a great family," he says.

Talk then turns to famous actresses, and the others chime in. Angelina Jolie, Halle Berry. Abu Islam grows quiet for a few minutes. "Who is she, the one in Unfaithful? Diane Lane! Oh, she is a wonderful woman!"

Abu Islam continues to opine about the wonders of Diane Lane, while I start doing Google image searches so the guys can update their Hollywood lust. I introduce them to Emmy Rossum and some of the female cast members of Game of Thrones, but they're not won over, preferring to stick to the classic desirable actresses of the nineties.

Later in the night, the big boss men stop by again. The others are haphazardly watching television in a room, flipping through channels. One of the pro-FSA networks is running a panel of sorts. Al Khaled tells them to keep it on this station. He walks up close to the television and sits down in front. The other men shrug their shoulders and turn away, leaving only Al Khaled to watch. After, we gather in the main sitting room for a bit, with Al Khaled and the general. They say that they will attack Hasakah soon, they are just waiting for weapons and ammunition. Then they ask if I've seen the new iPhone yet.

Chava has picked up my camera and is horsing around with it, again. Later I'll learn that over the course of the week that he took probably two thousand shots. Some of the ones he's shown me aren't half bad. I tell him he should think about being a photographer when the war is over. Without Yilmaz around to translate, he answers in broken English. "Don't like journalists," he says. "No like pictures. Like gun. Like soldiers."

He says he will stay a soldier after the war. He wants to be a "big boss." I tell him he should consider giving photography a shot since he really seems to enjoy it. "No," he says. "No, no, no. Don't like yes, only like no. No, no, no!" He turns it into a song, and from now on whenever I ask him to do something or to answer a question, he sings the song to me. He's also taken to trying to tickle me whenever I'm concentrating on jotting down notes.

Slowly, though, he's growing impatient. He keeps talking about Al Nusra, how he admires them. He gets upset when I try to take a picture of him when he has a moustache, since it is haram. He's started to dress more in all black.

It's the day before I'm due to leave Syria, and it's cleaning time at the base. All the cushions and pillows are thrown outside as the Iraqi starts to sweep and mop the floor. I step into the yard to chat with the others. At one point, the Iraqi pops his head out and asks, "I'm going to set a trap for shabiha, kill them, then steal a car. Who wants to come?" When I volunteer, he tells me he is just kidding, that he doesn't kill anyone.

Back inside, the cleaning is finished. The Iraqi is discussing the specs of different weapons with some of the young, less experienced members of the group. At one point, he gets up to get a briefcase. It's locked. It's the only thing I've seen locked in the entire time I've been in the clubhouse. He starts to undo the lock. He is handling the briefcase with finesse. I don't know what he could be pulling out. It could be human ears, for everything he's told me.

The Iraqi clicks the briefcase open and removes a bottle of air freshener. He sprays it into the air. Then he takes out one fancy bottle of moisturizing lotion and another of hair conditioner. He lays them on the bed. Lastly, he picks up an ornate handheld mirror and begins to apply the moisturizing lotion to his face while staring into it, cooing, "I love me."

Three days later, having left Syria, I'm in Sanliurfa, Turkey, when I suddenly remember to look up American female KIAs in Iraq. In the deadliest attack ever on female U.S. soldiers, four women were killed there after a suicide bomber, backed up by armed insurgents, ambushed a convoy in Fallujah.

EPILOGUE:

Shortly after I left, Jabhat Al Nusra arrested Yilmaz and Mossab for filming a battle in Raqqa. They were imprisoned for nearly a month before being released. Fighting in Ras Al Ayn started up again a few months later. The FSA was forced out and it is now the focal point of the battle between the YPG and jihadis. Marwan and Chava left to join a more jihadi-influenced group. Chava is currently fighting with them in a village near Ras Al Ayn. Abu Islam is staying with his family. Hilali was arrested and held by Jabhat and their affiliates for a week. He was released, but was recently arrested again and is still being detained. Fahd and the Iraqi are with another FSA group in a village near Ras Al Ayn.

Mossab and Yilmaz fled to Turkey after they were released. When I asked Yilmaz if it would be okay to publish this or if it would put him at risk with certain groups, he replied, "They can all go fuck themselves." He's still nonviolent. He still believes in the revolution more than anyone I've met.

Danny Gold is an American journalist based in Brooklyn. His stories, which focus on crime and conflict, have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, NBC World News, The Atlantic, Vice, and other publications. Follow him at @DGisSERIOUS.