Lou Reed is a bit of a hero of mine. When I was nine, Walk On The Wild Side was number 10 in the charts, and there had never been a record so languid and funky and cool and sexy. Doo de doo de doo de doo... So many of us wanted to be Lou with his shades and leathers, making out with the he's-that-were-she's and the she's-that-were-he's in the happening New York. A few years earlier, as the boss man in the Velvet Underground, he became the godfather of punk. Some songs, like Heroin, screeched with feedback, talked about the desire to nullify life and struck a chord with so many young people. Others, such as Sunday Morning and Pale Blue Eyes, were so tender, so ethereal, they barely existed.

Thirty-plus years on, he is one of our more unlikely survivors. He has seen off heroin and alcohol, and outlived his mentor Andy Warhol, heartbreak chanteuse Nico, and Velvet Underground guitarist Sterling Morrison. He restricts himself to water and Diet Coke, t'ai chi and wholesome foods, and he is still making records. Many of them are about loss and memory, growing old and evaluating life. A few months ago he released a double CD, The Raven, based on Edgar Allan Poe poems: although it was widely derided for its pretensions, the crystalline purity of a handful of songs touch the soul like in the old days. Now he has released a double-CD collection, NYC Man, which takes us from year zero to the present, and he is touring Europe to promote the albums.

Today he is in Stuttgart. It's not quite Berlin, where Reed made probably the most depressing album ever and named it after the city, but downtown Stuttgart is pretty bleak in its own right. I've heard bad things about Reed being uncooperative in interviews, but it's probably apocryphal. After all, I've been vetted by his people, and the sun is shining blissfully.

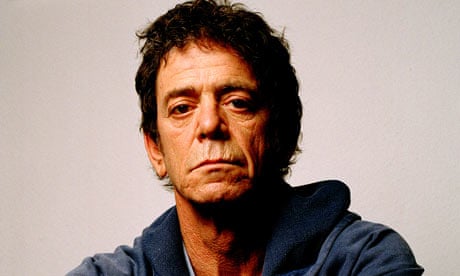

Reed is playing at the local concert hall, which looks made to measure for Reed in its concrete misery - the Barbican meets Belmarsh prison. We wait expectantly. Eventually, a people carrier draws up. A man in hooded sweatshirt jumps out, shadow boxes and runs inside: the camouflaged Reed makes it inside unimpeded. There's only the photographer, Eamonn, and me waiting, but Reed has lost none of his star quality.

After a quick snack, he is ready for a photograph. He's a small man but well-built - big pecs, big belly, tight T-shirt. He's 61 years old. He grips my hand and eyeballs me. Hi, I say. He stares. "He's not doing the interview in here, is he?" he asks the PR. No, she says. "So he doesn't need to be here for the pictures."

I'm sent off upstairs to a sterile, empty room to wait for him. He's not been that friendly, but once I tell him how I grew up to Walk On The Wild Side, we'll bond. There is so much to talk about; the smack years, if he can remember them; flirting with death; how his parents sent him for a course of ECT when they thought he was gay; how his relationship with a transvestite inspired Transformer; how he went back to live with his parents after he quit the Velvets and worked as a typist for his accountant father; how he interviewed celebrity fan Vaclav Havel; how he recovered his karma thanks to t'ai chi and his love for partner and performance artist Laurie Anderson.

I hear footsteps. It's the PR, Ginny. Bad news: Lou wants to soundcheck before we talk. Good news: we can listen. On stage for more than an hour, he drives his band relentlessly towards perfection. I'd forgotten what a great guitarist he is. After the soundcheck, I'm packed off back upstairs.

He walks in silently, with swaggering B-movie menace. Of course, he'll act the hard man, but my copy of NYC Man is on the table and once we start talking about his greatest songs he'll relax. I know he will. Hey, I say, when I look at this record it makes me feel nostalgic for my youth, and I didn't even write the songs, so God knows what it does for you. He gives me a withering look. "No, that's not what occurred to me. I was interested in making them sound as good as I can make them because the original mixes really hold up because they are recorded on to tape and they sounded really good."

Ah, typical Reed - hiding his heart behind the technobabble. So didn't it take him back, remastering all these classics? "I told you, I was interested in the sounds. There are things on some of these tracks that have bothered me for ever." He sounds as if he means it. Good actor, this Lou Reed.

I tell him I've been listening to The Raven and couldn't help noticing how reflective it seems. On one song he says one thinks of what one hopes to be and then faces up to reality; on another he asks if he had a chance to converse with his former self, what would come of it. They are familiar themes. In Perfect Day, written in 1972, the apparent idyll is undercut by the line: "You made me forget myself, I thought I was someone else, someone good."

"You can't ask me to explain the lyrics because I won't do it. You understand that, right." He gives me another look. Anyway, he says, this is just the character talking. Yes, but has he ever considered what his older self could teach his younger self, and vice versa? "I can't answer questions like that. What is it you really wanna know, because if it's personal stuff, you won't get it. So, you know, whaddya want?"

Reed has said in the past that he may as well be Lou Reed because nobody else does it better. I ask him if he thinks of Lou Reed as a person or a persona. "I don't answer questions like that."

Fine, I say, you tell me what we can talk about. But I don't feel fine. I feel unnerved and upset. "We can talk about music, is what we can talk about," he says.

But we can't, because if I ask what he felt like when he wrote Heroin, or what the line "shaved his legs and he was a she" was inspired by, that would be an encroachment. For Reed, everything is personal, except the mixing desk.

So I press ahead with the music. Back in the 70s, he and David Bowie and Iggy Pop were regarded as an unholy triumvirate. They broke down all kinds of barriers - between pop and performance art, male and female, lyricism and cacophony. There was a fluidity in their world; nothing was strictly defined. "I don't know what you mean," Reed says. Again, he stares me out, his tired eyes the colour of blood and chocolate. "I haven't a clue what you're talking about."

But I bet he has. Reed makes me feel like an amoeba. I want to cry. Look, I was a huge fan of yours, I say. " Was ?" he sneers. I still am, I say, but I'm less sure by the second. I desperately try to stick to the music. Soon after his most commercial album, Transformer, Reed made his least-commercial record, Metal Machine Music, an album of feedback. Some critics said it was his joke on the pop business. Is there any validity in that? "Zero." Is it something he can enjoy? "Well, I can." Which of his songs does he like best? "I don't have a favourite." Favourite album? "I like all of them."

Warhol, the Velvet Underground's mentor, believed that art shouldn't be tinkered with to appease the market. Did he teach Reed to value his own work? "It was great that Andy believed in us." Warhol fell out with Reed before his death, complaining that he never gave him any video work. I ask Reed if he wishes they could have made up before he died. "Oh, personal questions again."

But isn't the music shaped by his experiences and relationships? "Don't the people you're around shape the music, is that what you're saying? Everything does."

So why won't you talk about them? "You're not going to leave off that, are you? OK, let's not do it. We're not getting along. OK. You want to ask questions. I told you I can't do it so I can't do it. Thanks a lot. So I'll see you." He's off.

I shout after him, thank you, I've come all the way from England to see you, let's talk about what you want to talk about then. He sulks back in, and walks around me, as if weighing up whether to hit me. He sits down. "You wanna talk about music or not?" But, of course, he doesn't want to talk about anything.

I tell him that he's intimidating. (Actually, he's like the class nerd who worked out obsessively and graduated into the playground bully.)

"I'm not trying to intimidate you," he says, mock softly. He looks pleased. "I said don't ask me personal questions."

OK, then, can he explain The Raven to me? He tries and fails, but he does manage to say it took four years to make. Did it upset him that, after all that time, so many critics slated it? "I don't know anyone actually who does care what a critic says. Y'know, I was with Warhol, with Andy, and, the things they would say about him, up to and including when he died... and, of course, now he's quite possibly the top American painter."

The Raven features a singer, simply called Antony, with a wonderful, shimmering voice - almost castrato. I ask Reed where he discovered him, and say that he looks as if he could have popped out of Warhol's Factory 40 odd years ago. He says that his producer Hal Willner found him at the Meltdown music festival on London's South Bank. "After 15 seconds we thought: 'What an amazing voice'. Now, typical of you as an interviewer to say something as cheap as 'Oh, he looks like somebody who could have been around the Factory,' as opposed to, 'What a great voice'."

"I was going to come to that."

"Well, you could have started there."

"You never gave me a chance. Why are you so aggressive to me? What have I done to you? Why are you being so horrible?"

"I'm just pointing things out to you."

I'm lost for words. "I used to buy your records," I say pathetically.

"You used to."

"Are you really this aggressive in real life?"

"Didn't we just go through this? OK, fuck, you don't want to talk about music. ' Antony is someone who could have been in the Factory ,'" he mocks. "You don't say what a beautiful voice, my God!"

"Have I got to sit here and fawn to you? I was going to say he could be in the Factory because he's an original and his voice is stunning and ghostly. But you didn't listen long enough before attacking me."

"I didn't attack you. As attacks go, that is pretty mild. Come on! Come on ! Stop! Who you kidding?"

I ask him if he's happy. Listening to his bile, I can't help thinking this is one unhappy man. I apologise for the personal question.

"Jesus Christ!"

"I'm not a music interviewer. I do general interviews."

"Hahahahaaa!" And he is really laughing - even if it is the cruellest laugh I've heard. "Well, that explains it!"

OK, who's your music hero? "I love Ornette Coleman. I love Don Cherry. I love the way those guys play. Just my God!" For one second, he seems to be engaging. But only a second. "If you want to know records I like, on the web pages there is a top 100 or something like that."

I ask him whether we can discuss martial arts - strictly in the context of music. (There is a martial artist in his show) He nods. "I always thought martial arts was the most modern choreography we could have right now, and I always wanted to put it to music." What does t'ai chi do to his head? "I try to do it three hours a day. It does a lot of things. Mainly focus." And calmness? "I call calm focus."

Reed and Laurie Anderson were vocal campaigners against the war. How does he define himself politically? "I don't. I'm a humanist." What does he think about America at the moment? "These are really terribly rough times, and we really should try to be as nice to each other as possible." I think he's being ironic, but there's no hint of a smile.

· NYC Man is out on BMG.