Under the Surface

Part I • Part 2 • Part 3

It is 2021, and Gov. Tate Reeves is certain that the Jackson water crisis is nothing special. “Jackson has certainly got a lot of attention,” he told this reporter at a March 2 press event. “But at the height of the ice storm, Mississippi had 78 water systems that had boil-water notices.” By the time he said this, over 70% of those temporary outages had been repaired. But Jackson lagged far behind: weeks would pass before the water was again safe to drink.

The governor’s dismissal, two weeks into a crippling capital-city water crisis, was well-practiced. It echoed his earlier veto of a 2020 bill to allow Jackson residents a flexible repayment plan for outstanding water and sewer debt. (Just this week, Reeves relented, filing a version of the bill with more state control.)

“(The bill) provides no justification for its limited application,” Reeves wrote when he vetoed the 2020 bill. “There are ‘disproportionately impoverished or needy’ Mississippians throughout the state that have overdue balances for water and sewer services.”

This is one narrative of the Jackson water crisis. In the minds of some, especially Jackson’s most vocal opponents in the Legislature, it is the narrative: Jackson is nothing special, just another mismanaged city that fumbled a century’s worth of prosperity in a single generation, victim of little more than the self-inflicted wounds of petty corruption and laziness.

Another narrative is visible, far wider and far more complex. It begins, if one must pick a discrete beginning, 50 years ago.

‘We Will Not Drink from the Cup of Genocide’

Jimmy Swan, a once-popular country-music segregationist, was onstage in a white suit at a Jackson auditorium in the first days of January 1970. His musical career was over, and the first of two failed runs for governor was behind him. Still, he had the rapt attention of a crowd of more than 1,500 white people, all attending a boisterous rally for the newly minted Southern National Party.

A top goal was resisting the wave of school integration that was finally coming to southern states, after nearly two decades filled with violent white resistance gaining steam since the U.S. Supreme Court made segregated public schools illegal.

“Private schools are the only answer in this dark crisis,” Swan wailed, and so it would come to pass. New segregation academies and private-school attendance were exploding in Mississippi, and the capital city was no exception.

As 1970 dawned, the curtain was finally falling on the 15-year farce that was Mississippi’s so-called school integration after the U.S. Supreme Court tried to end it back in 1954’s Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision. The words “Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education” will never carry the national familiarity of Brown v. Board, but it hit Mississippi like a bolt of lightning. Children left public schools for Christmas break in late 1969, and many of them never returned, diverted to segregation academies to finish their education.

William Dalehite, a teacher and administrator in Jackson Public Schools in 1970, estimated in his book, “A History of Jackson Public Schools,” that more than 11,000 white families fled the district in the three years after the Alexander decision went into effect.

“Continued operation of racially segregated schools under the standard of ‘all deliberate speed’ is no longer constitutionally permissible,” the Supreme Court concluded in its succinct decapitation of the workaround that kept Mississippi’s public schools effectively segregated through the 1950s and ’60s. Justice William J. Brennan Jr.’s opinion made integration, at long last, unavoidable and urgent.

“School districts must immediately terminate dual school systems based on race and operate only unitary schools systems,” he wrote.

Yet it would not be long before a Supreme Court decision more to the segregationist movement’s liking would emerge. In 1974, Milliken v. Bradley placed limitations on the scope of Brown v. Board, asserting that the integration of the nation’s schools would not need to cross district lines. For the U.S., it meant that growing suburbs could remain white enclaves, bastions of segregated education, jealously guarded from Black encroachment through redlining and housing covenants.

For Jackson, it was the precursor to a great exsanguination, a draining of many of the city’s wealthiest residents to the surrounding suburbs, tax payments and all.

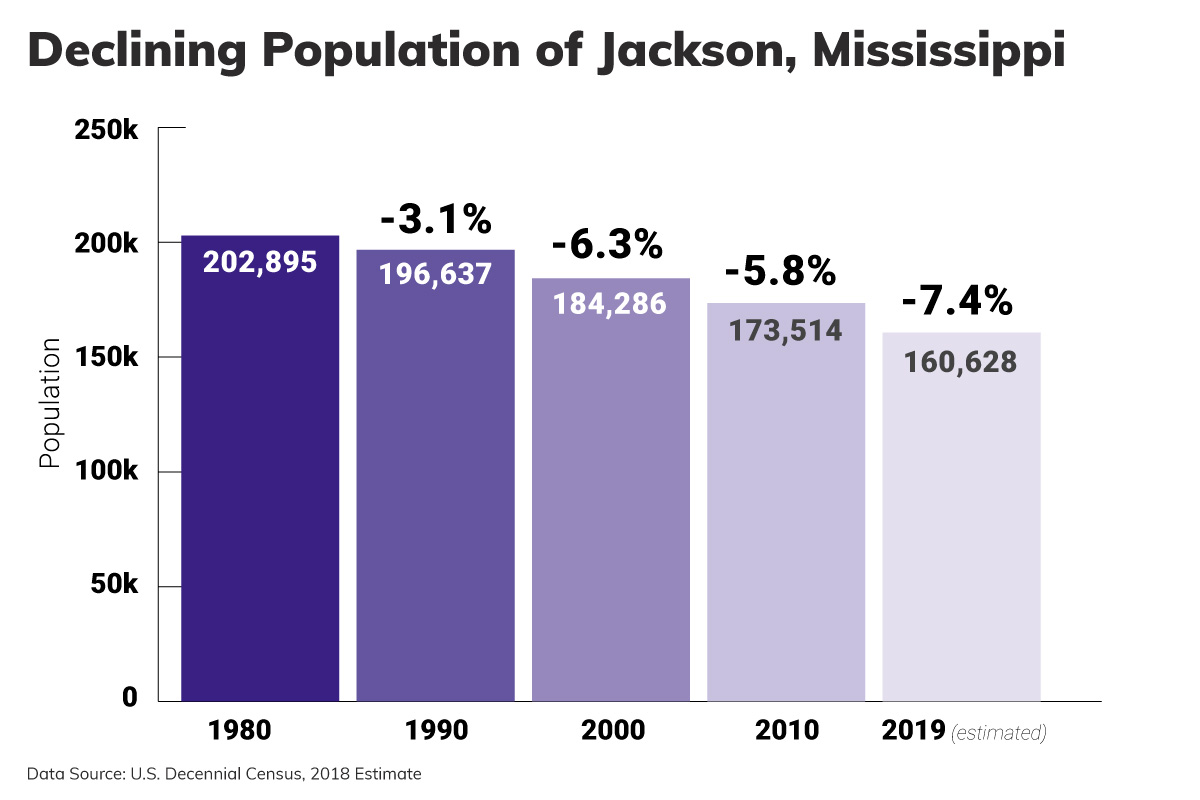

In the 1980 Census, Jackson’s population just exceeded 200,000, the peak of the city’s population, massively expanded in the previous decade before thanks to a series of annexations that ballooned the city limits. To date, it has never grown again, each decade taking another 10,000 or so from its population. Estimates from 2019 place the city population at just over 160,000, a 20% loss since its summit. The Jackson metropolitan area would trend in the exact opposite direction. This year, it is estimated to see the arrival of its 600,000th resident.

Jordan Rae Hillman, director of Jackson’s Planning and Development Department, explained to the Mississippi Free Press in a March 3 interview the links between white flight, annexations and the growing footprint of Jackson.

“If you look at the original city boundaries as they were through the 1890s up through the 1960s, you can see where the city used to have a small, dense footprint,” Hillman said.

Soon, she explained, Jackson was catering to the car, and to residents who wanted to live outside the tight city limits—away from integrated neighborhoods and schools. Jackson stretched itself thin to cater to them.

Hillman continued. “I would argue that much of the 1960 and 1976 annexations were an attempt to seek … neighborhoods that were built outside the city limits, but served by City water and sewer,” she said. “So you see some pretty significant population gains right before you start seeing the drop-off. We were expanding, capturing growth and people who had moved outside the original city limits.”

The size of the footprint of these trends is entirely unique in Mississippi, just as Jackson and the metropolitan area are unique in the state.

Few Mississippi leaders so dramatically illustrated the panic that would push thousands out of Jackson’s city limits in the years following integration as Gov. Ross Barnett. “There is no case in history where the Caucasian race has survived social integration,” he catastrophized in 1962. “We will not drink from the cup of genocide.”

Integration happened anyway, with Mississippians Black and white passing over the cup of genocide. Ironically, Jackson now drinks from the Ross Barnett Reservoir.

Bedroom Communities, Intercepted

The reaction to integration, which included white Jackson families immediately pulling 5,000 of their children out of local schools in 1970, was but one piece of the puzzle. Another came in 1972, an unintended consequence of necessary environmental reform. That year, the Water Pollution Control Act steamrolled through a veto from President Richard Nixon. Few took notice with the eyes of the nation affixed to the peace negotiations in Vietnam.

The consequences of the new environmental regulations, however, persist to this day. No longer could Jackson’s bedroom communities deposit their wastewater into minuscule sewage lagoons, where their runoff leaked into nearby creeks and rivers. Starting in 1972, the federal government required “secondary treatment” at a centralized point.

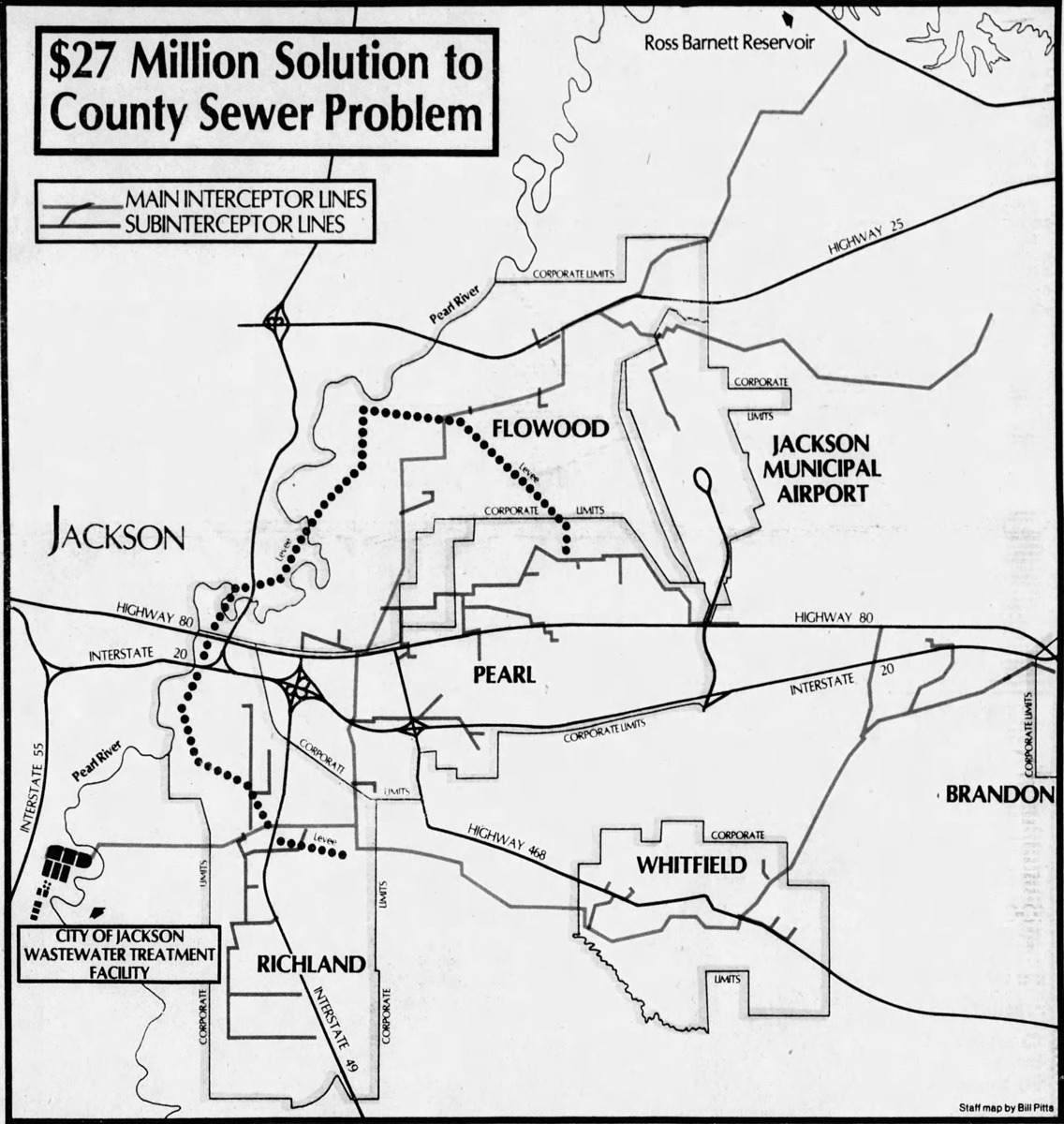

Within a decade, a sprawling web of interceptors would snake across the Jackson metro, drawing from lagoon after lagoon, the lines and their many sub-interceptors meeting at a central outflow point—the Savanna Wastewater Treatment Plant in south Jackson. The price tag was staggering, especially for the time, but the federal government was there to help.

The Clarion Ledger reported in 1981 that the Environmental Protection Agency willingly volunteered 75% of the entire production cost.

Those interceptors sketched a familiar boundary around a city on the road to a crisis. West Rankin, North Pearl, Flowood, Whitfield, Crossgates, Brandon, Reservoir and Hog Creek were names from a metro in full bloom, ringing a city at the apex of its growth, and at the precipice of a long and unending decline.

Then came the Reagan era.

‘I’m From the Government, and I’m Here To Help’

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan had the pulsating American id firmly in his grasp. Six years of morning in America had left the country in something resembling high noon. “I’ve always felt,” Reagan said in 1986, “that the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.”

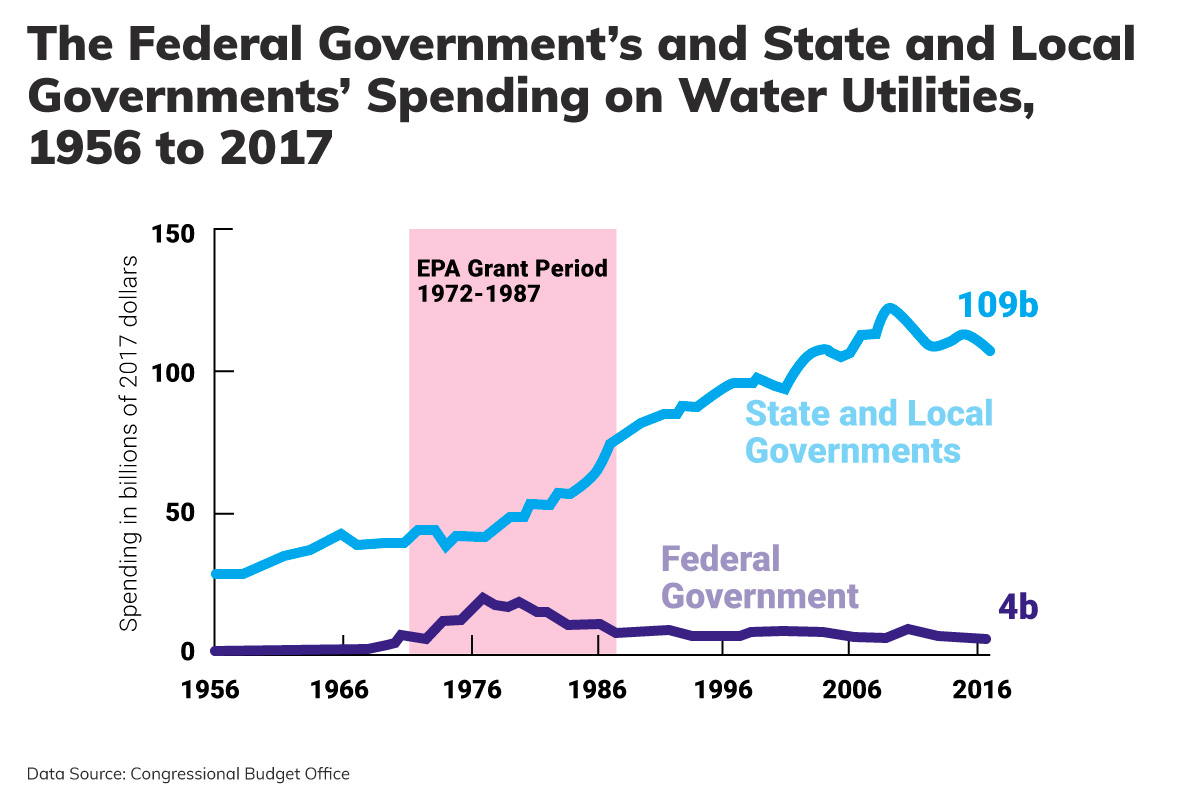

This philosophy was not so wryly worded when it showed up in policy, but show up in policy it did. Multiple amendments to the Clean Water Act over the decade dramatically reduced federal aid to municipalities for water and sewer infrastructure, capped off by the 1987 Water Quality Act. What was once a torrent was now barely a trickle, leaving cities to navigate state-managed, federally sourced loans, instead of the generous EPA grants that built most of their systems.

No regulatory relief accompanied the sea change in financial support. Cities like Jackson were and are still subject to expanding consent decrees, fines and environmental responsibilities. And yet, with its renewed spirit of self-reliance, the federal government expected these cities to pay for it with costly rate increases passed on to individual consumers. Costs rose, investment waned and a yawning labyrinth of pipes continued to age beneath the city.

Fast forward to March 2021: Jackson finds itself without water, torturous weeks becoming an interminable month. The reason is about more than just mismanagement, more than decades of delayed repair and deferred projects, white flight, regulatory burdens and federal disinvestment. It is about all of these events, happening at once, the experts explain: a constellation of competing priorities, incentives and complications no easier to disentangle from one another than the web of aging pipes beneath the city itself.

At the early March press event, Gov. Reeves drove his point home. “This is not an issue that is unique to our capital city,” he stated.

He likely had no idea how right he was.

Infrastructure Crumbles Into Trillion-Dollar Hole

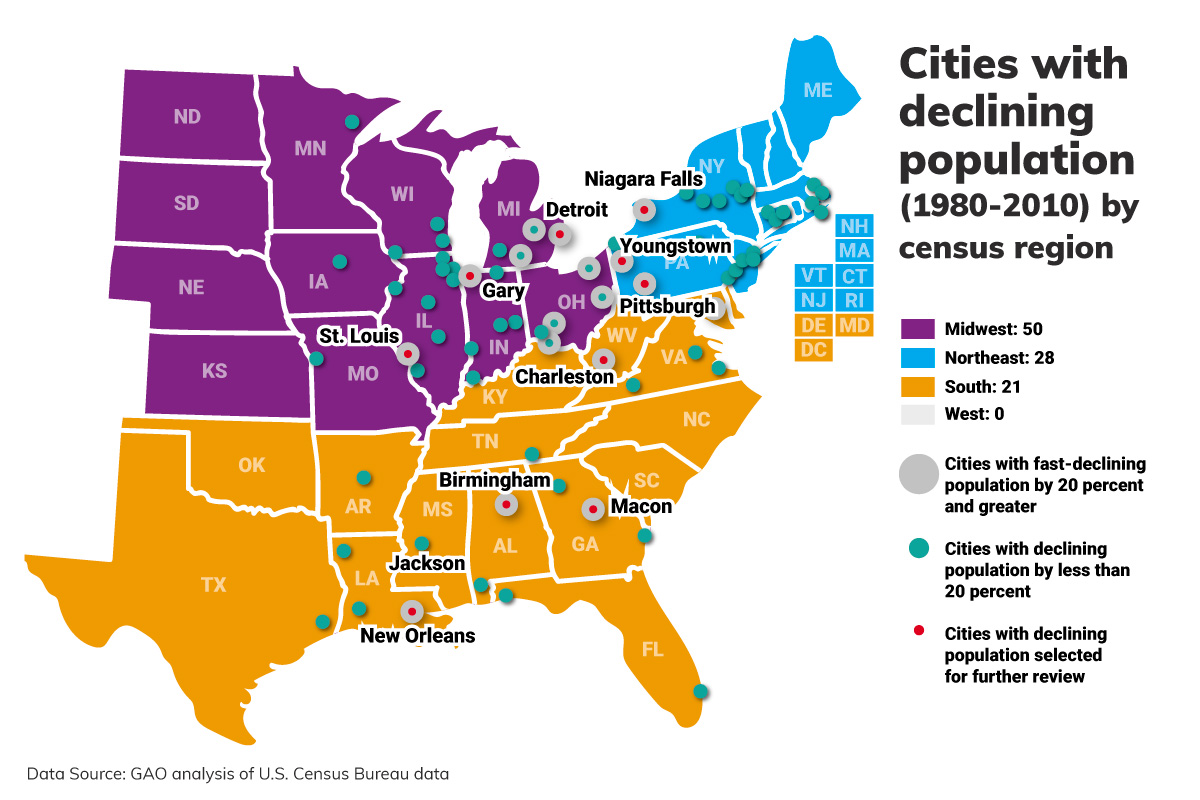

In 2016, Congress prompted the Government Accountability Office’s Natural Resources and Environment team to answer a burning question: What were America’s dying cities doing to keep their water-sewer systems alive? GAO tapped Director Alfredo Gomez to lead the study, which scanned the eastern portion of the country for “legacy cities,” large or mid-sized urban centers that had seen severe population decline in recent decades, Jackson among them.

On April 14, Gomez spoke with the Mississippi Free Press for an extensive interview. Though his team had passed over Mississippi’s capital in favor of mostly midwestern cities in their study, they identified Jackson as a key example of a southern legacy city, facing many of the same systemic burdens as places like Flint, Mich.

“We really tried to understand, for each of those cities, what are the particular challenges that they face? With declining populations, you have declining rates. If you don’t have the ratepayers, you’re going to have less money to do the work,” Gomez said.

Today, nearly 800 cities in the U.S. boast a population over 50,000. Gomez’ team identified 674, based on 2010 data. Of those hundreds of cities, 99 had consistently declining populations, scattered across the U.S., clustered in the Northeast and the Midwest especially.

Where the population declines were greatest, a familiar, persistent problem emerged. The GAO summarized its findings in a sprawling report.

“The discovery of lead in the drinking water in Flint, Michigan, in 2015 highlighted the risks that some cities confront in maintaining drinking water and wastewater infrastructure in the face of declining populations and deteriorating economic conditions,” the report states.

It continues, providing an odd mirror to Gov. Reeves’ comments on Mississippi’s capital city: “Indeed, Flint—once a large city with a peak population of more than 196,000 in 1960 that has declined to a midsize city with an estimated population of about 98,000 by 2015—is not unique in the challenges it faces.”

Jackson is one of those cities. Though its 2010 census data placed it closer to the middle of the pack for population loss, current estimates from 2019 reveal the greater than 20% population decline that makes Jackson one of the fastest-shrinking cities in the U.S.

GAO’s findings uncovered the same yawning gap between needs and capabilities reflected in Jackson’s 2013 master plan for water improvements. “Water and wastewater utility representatives whom GAO interviewed described major infrastructure needs, including pipeline repair and replacement and wastewater improvements,” the report reads.

For all the historical narratives aligning to create the Jackson water crisis, the heart of the problem is simple math.

“Water and wastewater utilities across the United States are faced with substantial costs to maintain, upgrade, or replace aging and deteriorating infrastructure—approximately $655 billion for water and wastewater utilities over the next 20 years,” the report states in an unflinching picture of the nation’s infrastructure burdens.

Those numbers are derived from two sources: the EPA’s Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Clean Watershed Needs Survey. In the years since the study, their estimates have only grown.

Mississippi’s 20-year drinking water needs in the 2011 drinking water survey were nearly $3.7 billion. That number crested to more than $4.8 billion only four years later in 2015. As of 2016, Mississippi’s 20-year wastewater needs exceeded $2 billion, and in that report the state is highlighted as one of the neediest in the U.S. in the category of runoff pollution control.

Jackson’s investment needs are not specifically broken down in the report, but it serves as the core of the capital metro containing one-fifth of the state’s entire population.

Reagan: ‘Loaded with Waste and Larded with Pork’

How could this have happened? Where did the gap between the nation’s water infrastructure needs and funding sources emerge? Jackson’s 2013 20-year capital improvement plan calls for $600 million just to keep the city’s water system afloat. Mississippi’s total need for that same period is nearly $7 billion.

A Congressional Budget Office report from 2018 provides a perfect snapshot of the problem. Federal spending on water utilities peaked at just over 30% in the late 1970s. In 2017, federal spending on water utilities had collapsed to less than 4% of the total, the lowest percentage of any infrastructure category—like highways, aviation and mass transit.

The table in question is a perfect illustration of the two trigger points in the nation’s expanding water needs and contracting water funding. The 1972 Water Pollution Control Act is the very moment that spending on water utilities takes off.

New regulatory burdens placed immense responsibilities on municipalities for the proper treatment and outflow of drinking and waste water. In the years that followed, total spending on water utilities ballooned across the nation by tens of billions of dollars.

The period of federal funding referred to as the “EPA Grant” period accompanied the new regulations. That peak of federal aid for municipal water systems lasted from 1972, with the Water Pollution Control Act, to the late 1980s, after a series of amendments to the original Clean Water Act brought it to a close.

This period spurred the expansion of water and wastewater systems across the nation. The Jackson metro interceptor project, which collected wastewater from the metropolitan area surrounding Jackson and delivered it to the Savanna Wastewater Treatment plant, serves as a perfect encapsulation of the projects and how significant federal contributions to them were.

“Jackson was ordered to build a metro wastewater treatment plant and the other eight participants (Pearl, Flowood, Brandon, Pearl River Valley Water Supply District, the Jackson Municipal Airport, the State Mental Hospital at Whitfield, Horseshoe Utilities at Crossgates, and the Richland Water and Sewer District) were ordered to tie into the system,” Charlotte R. Lancaster wrote for The Clarion Ledger in 1981.

Before the system was even completed, some of the municipalities surrounding Jackson were fighting to contribute as little as possible, including in Rankin County, Gov. Reeves’ home. “Richland has been receiving free sewer treatment since February and wants to pay as little as possible when it finally receives a bill,” the same reporter wrote. “If it gets its way, the Richland Water and Sewer District will be paying for less than the other eight cities and districts that agreed to finance a $27 million sewerage project in 1975.”

That fight was over less than $10 million. The EPA provided the other $21 million.

The entire process, with all its ambitious new projects and gargantuan federal spending to support them came to a crashing halt in the 1980s—the Reagan era of deregulation and funding cuts. Federal support in the form of EPA grants virtually disappeared, replaced instead with access to State Revolving Loan Funds—money that would be useless to municipalities without the revenue to pay them back.

The fight over the Water Quality Act of 1987 was a bitter one. Congressional supporters of environmental funding clashed with Reagan over the cuts he wanted to federal funding for clean water projects. Reagan repeatedly vetoed attempts to spend on water initiatives, citing the national deficit.

Sen. Wyche Fowler Jr., a Georgia Democrat, discussed the legislation that would formally mark the end of the construction grants era, touting the restraint the new legislation represented.

“This legislation spreads $18 billion over nine years for (EPA’s) Construction Grants Program … almost half of it—$8.4 billion—is targeted for State revolving loan funds. Such State loan funds will help create a self-sustaining source of money for States to finance local construction,” he said on the floor of Congress early in 1987.

Even though the 1987 Act was the definitive end to the period of large-scale EPA investment in municipal water systems, Reagan vetoed it immediately, decrying it as “loaded with waste and larded with pork.” In fact, he had pushed for $12 billion more in cuts.

Congress overrode his veto, but the numbers spoke for themselves: The era of EPA-funded municipal water systems was over.

Municipalities Cut Loose to Go It Alone

To Dr. Aaron Packman, professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Northwestern University, dismissive characterizations of water-system funding as decadent government welfare perfectly depict the era’s shift in federal philosophy, pork barrel and all.

“This is the federal government giving up its responsibility to make sure that people have good water systems,” Packman told the Mississippi Free Press in an April 16 interview. “And this goes along with the whole (welfare) argument—should people be supported by centralized federal investments, or should they be cut loose on their own?”

Packman’s organization, the Center for Water Research, has been examining the federal pullback from water infrastructure and the devastating impact that change has had for years. “The federal government left every municipality in the country to deal with its own water issues,” Packman said.

For many cities around the U.S., especially those with shrinking populations, the only solution was hiking water rates to keep up with inflating costs.

“Most of the 14 utilities GAO reviewed raised rates annually to cover declines in revenues related, in part, to decreasing water use from declining populations, or to pay for rising operating and capital expenses,” the GAO report explains.

But increasing those rates came with a cost. “If you push these kinds of very costly, large-scale infrastructure investments to local communities,” Packman said, “a number of them will not be able to pay for it. And then, for political reasons, a lot more will just defer all that maintenance on it.”

The GAO report expressly identifies the expense of water and wastewater utilities as growing faster than other forms of infrastructure, and indeed, as growing faster than the rate of inflation itself.

“According to an American Water Works Association survey, typical water and wastewater bills for residential customers have increased due to rate increases from 2008 through 2014 by 41 and 37 percent, respectively. In addition, according to a 2015 study, prices for water and sewer maintenance continued to rise at a much higher rate than the overall rate of inflation, in contrast to price trends for other utilities, including electricity, natural gas, and telecommunications, that are tracking at or below the rate of inflation,” it reads.

Jackson’s water billing problems have their own sordid history, but the report confirms that the cost of water and sewer systems is rising out of the reach of many customers, especially in poverty-stricken areas.

“As rates increase to pay for replacing or rebuilding existing infrastructure, they may become unaffordable—that is, high enough that some customers may be unable to pay their water and wastewater bills without financial hardship.”

Danks: ‘Jackson Was the Mothership’

Dale Danks Jr. was the mayor of Jackson from 1977 to 1989, during the later period of the lucrative EPA grant era, when federal funding for municipal water systems reached its zenith, then waned and collapsed. In a March 9 interview with the Mississippi Free Press, he recalled the shifting federal support.

“Jackson was the mothership, so to speak,” he said, referring to its importance to water and sewer projects for the entire metro. “The feds lowered the financial assistance to deal with the metropolitan area, as it relates to water and sewage. I want to say at one time they contributed 90%.” Danks acknowledged that his recall was imperfect, all these decades later.

Whatever the number, once that funding was gone, the City had a massive hole to fill. “We had to find some source to fill the gap of reduction in participation by the feds,” he explained. Danks did raise the water rates in the late 1980s, precisely as the federal government expected municipalities like Jackson to do.

What happened to Danks then was entirely unsurprising: He was voted out of office—in his eyes, because of water rate hikes most of all.

“Frankly,” Danks said, “it’s what beat me when I ran for re-election.”

Whether or not that was true, Danks’ experience with water infrastructure shows the fundamental tension of the “shift in philosophy,” as Gomez put it, from federal support to “local self-sufficiency.” Local funding is not done at the bird’s eye level. Few circumstances have the potential for such immediate blowback as municipal price increases passed directly to residents.

Packman sees immense danger in the intersection of Jackson’s dwindling tax base and the lack of federal support. “Now, you have the combination of (funding) infrastructure where there’s no longer federal investment, and lower local tax base,” he said. “That is a recipe for disaster. And the reason we’re seeing (the consequences) now is that infrastructure is a long-term investment.”

Now in 2021, decades of underfunding have damaged that long-term investment. The Mississippi Free Press spoke to virtually every living mayor of the City of Jackson for this story. Each defended his record in his own way. Some pointed to infrastructure spending during their tenure. Some highlighted their dire warnings over the growing gap between revenue and expenses.

What none of them was able to accomplish was a mending of the rift, filled with unworkable math, that opened in the 1980s.

“(Jackson) is not an isolated incident,” Packman asserted. “This is a persistent set of trends.”

Examining Solutions

The primary focus of the GAO study was to examine the solutions that legacy cities like Jackson pursued to address their crumbling water systems. With the precipitous decline in federal support, neither rate increases nor collecting overdue water bills from poor residents are sufficient to address growing needs.

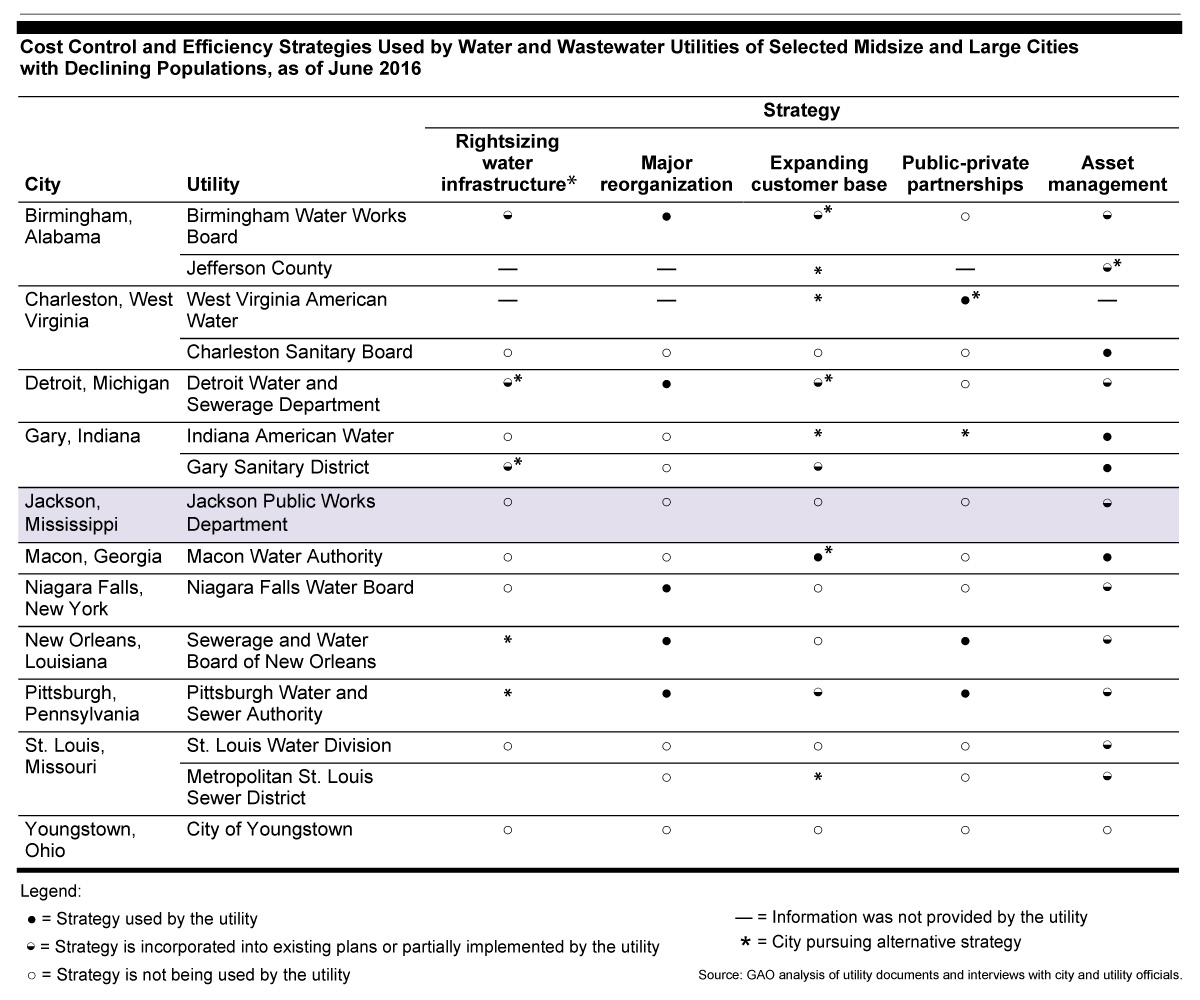

Gomez and his team identified five major strategies for addressing chronic water-system issues: rightsizing water infrastructure, a major reorganization of the city’s water utilities, expanding the utility’s customer base, public-private partnerships and asset management.

Jackson Public Works Director Dr. Charles Williams examined the comparative solutions that GAO found in a March 13 conversation with this reporter.

Williams discounted two of the solutions out of hand, citing Jackson’s geography as essentially precluding those options. Rightsizing water infrastructure, which entails the removal of redundant and unnecessary facilities and transmission lines or the downsizing of the service area, and expanding the customer base are unlikely to be strategies Jackson pursues now or in the near future.

“Jackson is a large city, and a lot of residents rely on that connectivity of the water distribution system and our wastewater treatment facilities. So, no. A reduction in that area is not going to benefit us, because our services are built on supplying Jackson from north, east, west and south,” Williams said.

Any plan to expand the water utility’s customer base faces the same problem. “We have Byram,” the public works director explained. “We service water there, but there’s no other suburbs that I believe we could expand to. I think the only way that we could have that expansion would be to increase the population though housing.”

Public-private partnerships, like partial takeovers of utilities, are not expressly off the table, but Williams suggested that lack of funding and consensus over who might take ownership of what meant the possibility was far down the road. “For you to have a true public-private partnership,” Williams said, “both sides have to have funding in place. I don’t think we’re financially there, yet.”

The remaining two solutions are not only on the table; they are in the works. Williams confirmed that the City is exploring asset management—which Gomez and his team highlighted as a key technology that allows cities to anticipate system needs and complete repairs before an emergency occurs.

The GAO report explains the value of asset management. “A water utilities’ management professional estimated that emergency repairs can cost three to four times more than regular repairs—for example, if the cost to repair 1 mile of pipe is $550,000, the cost to repair this same pipe in an emergency could range from $1.7 million to $2.2 million,” it states.

Williams explained that the city’s new asset management software should be online by the end of the year. “We’re in the process of doing it now,” he said.

“Part of that is (using) Cityworks,” he continued. “Cityworks is software that allows you to put all of your assets, your equipment, everything into a database. Then it can help you determine when you’ll need to repair, when you made the last repair, those types of things. (All) to keep up with your equipment and give you a better way to maintain your assets.”

More ambitious are the City’s plans for a major reorganization of its public works department. “It’s funny that you ask (about reorganization),” Williams said. “We actually have a consultant who presented to the mayor and the city council the possibility of breaking up the Department of Public Works.”

Williams cautioned that the plan was still preliminary—a proposal, not a concrete plan. But if implemented, the Jackson Public Works Department as it operates today would be broken up into three separate entities.

“What we have proposed is breaking out the Department of Public Works, the Office of the City Engineer, and then the Water and Sewer Business Administration,” he explained.

Williams continued: “You have a traditional public works department that would cover maintenance—of roads, water, distribution lines, collection systems, and our plants. All of that would fall under their scope of work.”

Another department would handle large-scale projects. “The Office of the City Engineer would handle all of your capital improvement projects in the city: those that would need to be engineered, procured and then bid out.”

Finally, Williams finished, the City of Jackson would have its own administrative department for handling the funding of the city’s enterprise fund, which pays for its water and sewer system. “The Water-Sewer Business Administration Office would be totally separate. It would deal strictly with billing and revenue.”

Some cities have separate administrations for water, sewer and drainage management. Jackson does not appear to be pursuing that strategy, a decision Packman sees as a wise one. Williams said that funding makes the systems fundamentally intertwined. “They’re together because the enterprise fund is the primary mechanism for both of those entities. They’re joined together—they can’t be separated,” he said.

In a sense, the proposal would represent a downsizing of Williams’ own authority over all of these disparate roles. But the public works director was enthusiastic about the idea. “(It would) better allow for more focus on areas that need to be addressed—not having them completely under one umbrella, which makes it a difficult task for a public works director: trying to cover so much ground,” he said.

Though the City of Jackson is now on track to incorporate some of the GAO’s identified tactics by the end of the year, a comparative analysis with the other shrinking municipalities the GAO examined shows that, even in 2016, most had implemented at least some major strategies for combating water system decline. Jackson had not, focusing instead on emergency repairs for a transmission system in a deepening crisis.

Williams acknowledged that, even compared to other legacy cities suffering from some of the same problems, Jackson was behind the curve on implementing systemic solutions at the municipal level.

“If we had done this maybe 20, 30 years ago, when we had a higher population and more people paying into the enterprise fund, maybe we would not be hit as hard right now. Maybe we’d be more able to work through these issues. But, unfortunately, we don’t have that luxury,” Williams said.

Federal Change On The Horizon

If Jackson is finally on the road to more ambitious solutions for its crippled water infrastructure, the federal government appears to be following suit, in theory, if not yet in fact.

President Joe Biden’s “American Jobs Plan” describes an enormous federal investment in infrastructure of all stripes, chief among them water and sewer systems.

“President Biden’s plan will eliminate all lead pipes and service lines in our drinking water systems, improving the health of our country’s children and communities of color,” the plan promises. It continues, further promising an investment of federal dollars so significant it would, in a sense, return the nation to the EPA grant era of half a century ago.

“Aging water systems threaten public health in thousands of communities nationwide. President Biden will modernize these systems by scaling up existing, successful programs, including by providing $56 billion in grants and low-cost flexible loans to states, Tribes, territories, and disadvantaged communities across the country.”

But the “American Jobs Plan” is still a proposal, and it faces a hostile congressional minority that is certain to tamp down on its proposed infrastructural largesse.

More immediate are the changes in language coming from some government agencies—specifically the EPA. Newly sworn-in EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan directed the agency to pursue environmental justice, specifically for marginalized communities like Jackson, in all agency plans and actions.

“Too many communities whose residents are predominantly of color, Indigenous, or low-income continue to suffer from disproportionately high pollution levels and the resulting adverse health and environmental impacts,” Regan wrote. “We must do better. This will be one of my top priorities as Administrator, and I expect it to be one of yours as well.”

In an interview with the Mississippi Free Press, Jeneanne Gettle, director of the EPA’s Water Division in Region 4, which includes Mississippi, acknowledged that the EPA’s primary relationship to funding municipal water and wastewater systems was through the revolving loan funds.

“What we do now is the ultra low-interest loans—and we do encourage use of every dollar that is available through the (revolving loan funds) to go into infrastructure needs into the communities,” Gettle said.

Regan’s words are a welcome sound to municipal leadership chafing under the burden of environmental regulations without the assistance of federal aid to fix the problem. But unless those words are accompanied by a new avenue for funding—and not in the form of debt—Jackson leadership has stressed that the revenue gap will remain.

The GAO report reveals that, for all the many grant and loan programs, the system is not set up to specifically account for cities like Jackson, which cannot merely expand rates and pair the measure with a steadily growing tax base.

Rep. Paul Tonko, the Democratic congressman from New York who ordered the GAO report, summarized its findings in a 2016 press release: “It illustrates what we have seen for years–legacy cities need additional assistance, and our existing federal programs are not designed to address their structural and demographic challenges.”

The report itself was more explicit. “None of the six federal programs we reviewed that can fund water and wastewater infrastructure needs were specifically designed to provide funds to cities with declining populations for water and wastewater infrastructure projects,” it stated.

‘Letting People Suffer’

This is the wellspring of the Jackson water crisis, the history of a city’s decline. White flight battered and drained it, grasping at fleeing suburban residents overextended it, and the federal government abandoned it to squeeze revenue out of a crumbling tax base to pay for an ever-more expensive water infrastructure. The city is behind on measures that could offset fractions of the decay, but expert analysis of legacy water systems reveals a nationwide gap between need and ability that municipal policy alone cannot mend.

Finding a comparative example for this series—a city much like Jackson—proved elusive at best. Midwestern cities have their own socioeconomic dynamics, and many struggle with combined water-sewer systems unique to the region.

Disentangling New Orleans’ many problems from the devastation of Hurricane Katrina is virtually impossible. Macon, Ga., essentially merged with its surrounding Bibb County—the idea of a consolidated tri-county metro under the mayor of Jackson is, at this point, somewhere in the realm of science fiction, considering the ongoing political and racial dynamics between the capital city, its suburbs and the State of Mississippi.

Perhaps there is no city quite like Jackson, in Mississippi nor anywhere else in the U.S. But the historical currents that drove its water system further and further from solvency are not unique, and so far, not changing.

Packman asserts that the federal disinvestment in the 1980s amounted to a lack of trust in municipalities to manage federal money, one that has persisted ever since.

“The real objective is to maintain a functioning, safe water system. There’s a huge disconnect, and it reflects a political philosophy—an ideology,” Packman told the Mississippi Free Press. “I do think it has really equated to, and until recently, still equated to just letting people suffer.”

This is Part 3 in Nick Judin’s “Under the Surface” series on Jackson’s water infrastructure, historic causes for its decay and potential solutions. Part 1 can be found here. Part 2 can be found here. Nick’s full and growing Jackson water crisis archive since March 1, 2021, is here.