I’ve just got back from Slovenia, where I gave a lecture on the Euro crisis to the Institute of Labour Studies (http://dpu.mirovni-institut.si/roberts2013.php). The Institute was set up by a group of economics students who support a Marxist analysis. They are doing a great job in trying to develop Marxist economic theory by inviting leading Marxist scholars and writers to do lectures or participate in conferences. The Institute is really a spin-off from Slovenia’s unique Workers and Punks University (http://www.dpu.si/), a sort of alternative university formed by radical young people to present an alternative to conventional educational institutions and dominant ideas that there is no alternative to the current society. The Institute is funded by the Peace Institute in Slovenia, leftist parties and think tanks in Europe. Anyway, they asked me to present a lecture on the Euro crisis, to coincide with their enterprising launch of a new Slovenian translation of Marx’s Capital Volume 1.

The subject of the lecture could not have been more apt, because tiny Slovenia, a nation of 2 million people wedged along the Alps, between Italy to the west and Austria to the north, is the only Balkan (ex-Yugoslav) country to be in the Eurozone. Slovenia has been relatively more prosperous than the other Balkan states and avoided the internecine wars that took place between Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Kosovo after the collapse of the ‘communist ‘ Yugoslav federation. It entered the EU and the Eurozone with great hopes of going forward. Then the global economic crisis erupted from 2007 onwards. Slovenia seemed to avoid the worst for a while. But now it has been hit with tremendous damage. The economy is in a deep recession that began in 2011. The response of all the political parties has been austerity – under the direction of the EU institutions. That has been a disaster and eventually Slovenians had had enough. Last November there were huge demonstrations demanding an end to austerity and a plague on all the political leaders. This heightened when it was found that both the leaders of the centre-right and centre-left appeared have been involved in corruption scandals.

The Slovenian economic crisis is very similar to that of Ireland. Slovenia’s state-owned banks had been engaged in massive loans to Slovenian companies, mainly in construction and real estate, stimulating a huge commercial property boom that came crashing down when the global economic slump began. And just as in Ireland, it has been found that the politicians were in collusion with builders and developers to promote a crazy credit boom, taking a slice of the action for their troubles.

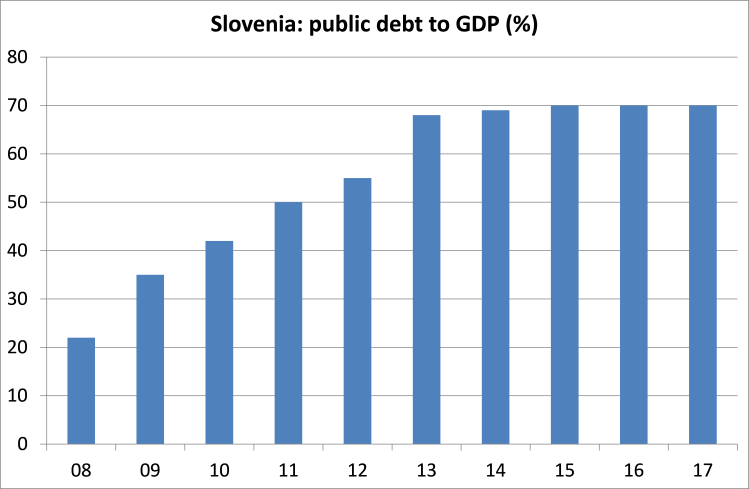

For a while this was covered up, but with unpaid loans now reaching 20% of all lending, the banks are close to bust. A bailout of the banks is now on the agenda and Slovenia needs at least €5bn by the summer to do it to avoid collapse. Of course, the EU and IMF came up with the usual ‘Irish solution’, which was to hive off all the bad debts into a ‘bad bank’ which the taxpayer must ‘own’, while the cleansed banks are given funds to recapitalise, with the aim of selling them off to foreigners or others as soon as possible. The Slovenian government will then be left with a public sector debt that will have risen from 23%of GDP in 2008 to 70% by 2017, a massive burden on taxpaying Slovenians.

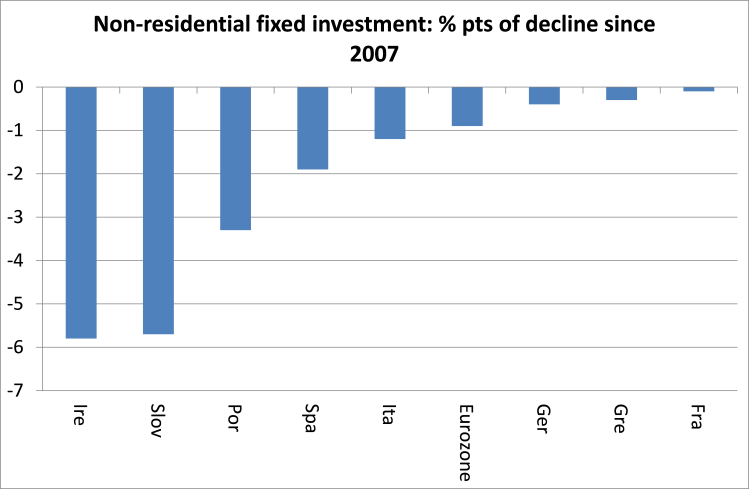

And the level of debt built up in the credit boom has destroyed the ability of the banks to provide more credit and companies funds for new investment. Non-residential capital investment has fallen by nearly 6% of GDP since 2007, as the Slovenian capitalist sector went on strike or bust. That drop is second only to Ireland in the Eurozone. The depression is mega-sized for such a small country.

Since the protests began, various coalition governments have come and gone. As I delivered my lecture, a new left-leaning coalition was being endorsed with a female premier, Alenka Bratusek, who is supposedly an ‘expert on finance’. The new coalition is now faced with finding the money to bail out the banks or going into an EU-IMF ‘Troika ‘ programme as now Cyprus will shortly. Bratusek says she can deliver economic growth and fiscal austerity at the same time – if so, that will be a first in this euro crisis. Of course her aim is not really to relieve the burden of Slovenians, but as she says, but to “reassure financial markets” with a program of “three key things: overhaul of the banks; consolidation of public finances in a way that not hurt growth (!); and better management of state assets (does this mean privatisation?)”.

And the Euro crisis continues elsewhere. As I write, the EU leaders have just decided on a Troika bailout programme for Cyprus, where the banks have been driven to the wall through acting as a conduit for Russian oligarchs’ ‘hot money’ flows. Cyprus’ economic boom prior to the crisis was based entirely on providing a safe haven for illicit Russian funds, laundering them so they could then be sent back into Russia ‘clean’. Cyprus attracted $119.7bn of Russian “investment” in 2011 while itself transferring $129.9bn to Russia the same year, equivalent to more than five times the island’s annual output, according to Global Financial Integrity, a US-based money laundering watchdog. Raymond Baker, GFI’s director, said the amounts reflected “round-tripping” of illicit funds exported from Russia to companies based in Cyprus. The funds then flowed back as legitimate investment.

“I don’t think Cyprus has cleaned up its act. It’s still a centre for disguised entities and for money of suspect origin,” Mr Baker said. “I think the amount of legitimate Russian money coming into Cyprus would be minuscule.” Cypriot banks used these deposits to invest all over the place: in Greek assets (!) and in property all over Europe. Now these assets are worthless and they are bust and yet they must meet their obligations to the Russian depositors. The EU leaders were divided about what to do: they did not want to bail out Russian mafia, but they did not want to set a precedent by reneging on bank debts in case this was used by anti-austerity movements, as in Slovenia, to do the same. Under pressure from the IMF, the EU leaders have decided that the Russian depositors must take a 10% ‘haircut’ on their deposits, so that of the €17bn needed, only €10bn will now come from the Troika. Even so, that is a huge burden for Cypriots, equivalent to 40% of annual GDP. This will be agreed to by Cyprus which has just elected a centre-right president pledged to do so, after throwing out a ‘Communist’ president who was also imposing austerity.

And so it goes on. Italy is politically paralysed and cannot yet form a government because nobody wants to grasp the nettle of imposing more austerity on an electorate that voted by a large majority against it. And in Greece, the right-wing coalition government twists and turns with the Troika about how to meet the fiscal targets without imposing even more severe measures that could break up the coalition and engender new elections that could return an anti-Troika leftist party to power. The government is being asked to sack 150,000 public servants over the next three years, putting all of them on 40% pay right now, along with lots of other measures designed to squeeze yet further the population which has already lost 30% of real incomes. A deal will be reached with the hope of the government that Greeks will just continue to bear the burden until the Greek economy starts to recover.

But with the Eurozone still in recession this year, even France is getting into trouble. The French official GDP target for this year was 0.8% but this has now been lowered to +0.2-0.3%. This compares to +0.1% EC forecast. In 2012 growth was zero. The French budget deficit is seen officially at -3.7% of GDP this year from -4.6% in 2012 (both French government and the EC). This failure will increase the stresses between Germany and France over meeting EU long-term fiscal targets to get deficits and debt down. All the bailout countries are getting ‘more time’ to meet their targets. But without growth, it cannot be done.

And that is what my lecture dealt with: why this is so difficult for the EU leaders to achieve. The title of the lecture was The euro crisis is a crisis of capitalism. I could have added “and not a crisis of the euro”. In other words, even if the euro was to collapse and EMU states returned to running their own monetary and currency policies, the crisis would not go away and may even be worse. That’s because the euro crisis is the product of the failure of the capitalist mode of production globally. It has had the worst impact on the weaker capitalist economists like Greece, Portugal or Slovenia, but it has hit all.

In my view, that is the point that must be remembered. The crisis is only partly a result of the policies of austerity being pursued, not only by the EU institutions, but also by states outside the Eurozone like the UK. If that is right, then alternative Keynesian policies of fiscal stimulus and/or devaluation where possible,will do little to end the slump and will still make households suffer income losses.

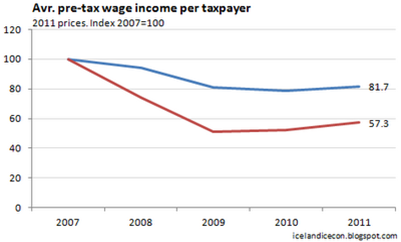

Austerity means a loss of jobs and services and thus income. Keynesian policies will mean a loss of real income through higher prices, a falling currency and eventually rising interest rates. Take Iceland, a country outside the EU, let alone the Eurozone. Devaluation, or Keynesian-style ‘beggar-thy-neighbour policies have still meant a 40% decline in average real incomes in dollar terms and nearly 20% in krona terms since 2007.

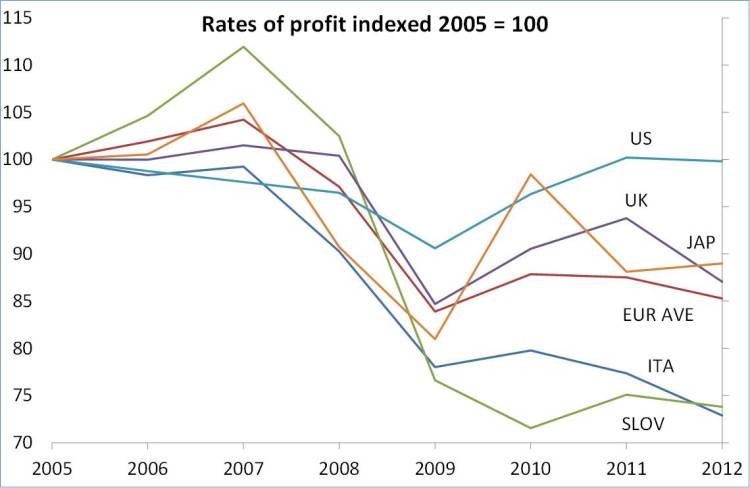

The Euro crisis is product of the slump in global capitalism and the subsequent failure to recover is the same. Profitability in most capitalist economies is still well below the peak of 2007 (the US is the only exception) and for economies like Italy and Slovenia it is still heading downwards.

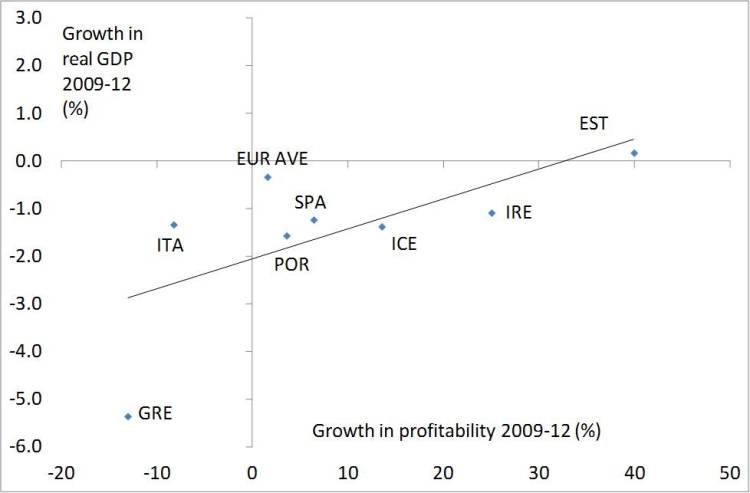

In the lecture, I correlated profitability with growth since the trough of the Great Recession (graph below). The trend line is positively sloped. Estonia and Ireland have seen the biggest recovery in profitability (through austerity and cutting wages and living standards for the population, along with massive emigration of the unemployed). As a result, they have had the best GDP recoveries – such as they are. Where the recovery in profitability has been weak or non-existent, real GDP has contracted the most since 2009.

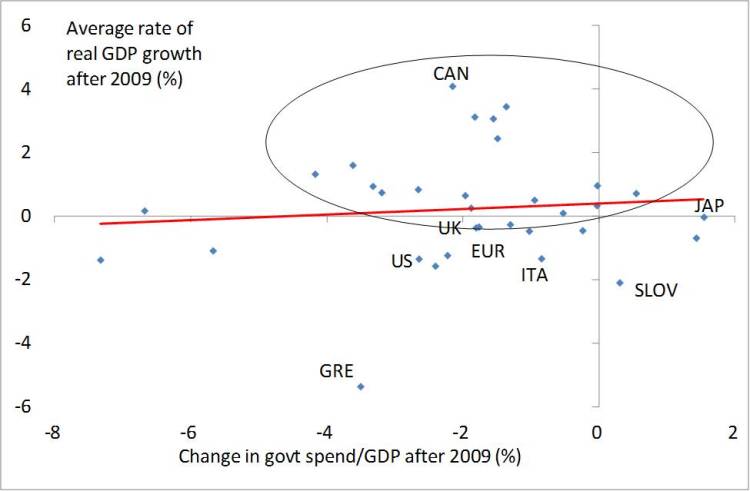

The correlation between profitability and growth is much better than between government spending and growth. Countries where government spending to GDP has increased since 2009 (i.e. Keynesian-style stimulus) like Japan and Slovenia (until now) have not grown at all (see graph below), while there are many countries that applied austerity and reduced government spending to GDP after 2009 and they have achieved some growth. There is no real correlation between growth and austerity (the trend line is almost flat), whatever Keynesian multipliers might indicate (see my post, The smugness multiplier, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/10/14/the-smugness-multiplier/).

And the build-up of debt, not just for banks, but also for the non-financial capitalist sector is exerting downward pressure on the ability of capitalist economies to recover quickly, even after cutting jobs, closing down businesses and ending investment to reduce the cost of capital. The more the growth in private sector debt before the crisis, the smaller the recovery has been. The IMF graph below shows how the level of private debt has held down the recovery. Balance sheet stress is heavier on the weaker EMU states and the financial centres of the UK and the US.

Of course, there are special features involved in the euro crisis. Capitalism is a combined but uneven process of development. It is combined in the sense of extending the division of labour and economies of scale and involving the law of value in all sectors, as in ‘globalisation’. But that expansion is uneven and unequal by its very mode as the stronger seek to gain market share over the weaker. Yet the Euro project aimed at integrating all European capitalist economies into one unit to compete with the US and Asia in world capitalism. But one policy on inflation, one short-term interest rates and one currency for all is not enough to overcome the centrifugal forces of capitalist uneven development, especially when growth for all stops and there is a slump.

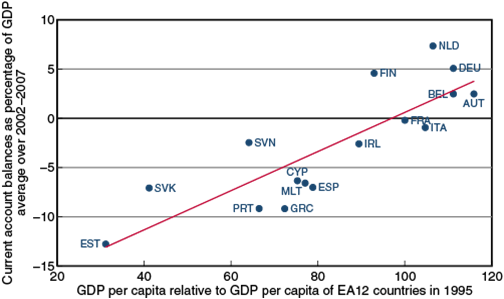

The aim from 1999 with the Eurozone was that the weaker economies would converge with the stronger in GDP per capita, fiscal and external imbalances. But instead, as the IMF explained in a recent paper (http://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2013/02/15/europe-toward-a-more-perfect-union/): “During the years that followed the euro’s introduction, financial integration proceeded rapidly and markets and governments hailed it as a sign of success. The widespread belief was that it would benefit both south and north—capital was finally able to flow to where it would best be used and foster real convergence. But in fact, a lasting convergence in productivity did not materialize across the European Union. Instead, a competitiveness divide emerged. As the financial crisis gripped the euro area in 2010, these and other problems came to the fore…. In fact, there has been little absolute real convergence in the euro area. Those euro area countries that had low per capita incomes in 1999 did not have the highest per capita growth rate”. The graph below rises up from left to right, instead of being flat.

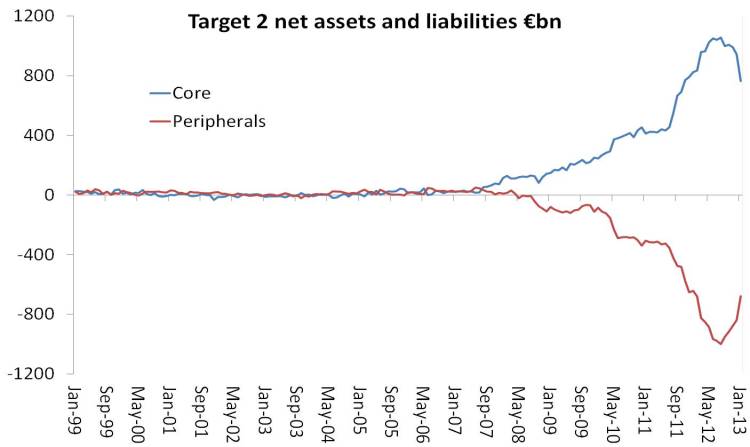

As I show in the lecture, the global slump has dramatically increased the divergent forces within the euro, threatening to break it apart. The fragmentation of capital flows between the strong and weak Eurozone states has exploded. The capitalist sector of the richer economies like Germany have stopped lending directly to the weaker capitalist sectors in Greece and Slovenia etc. As a result, in order to maintain a single currency for all, the official monetary authority, the ECB and the national central banks have had to provide the loans instead. The Eurosystem’s ‘Target 2’ settlement figures between the national central banks reveals the huge divergence within the Eurozone, although in recent months there has been some reversal back towards convergence.

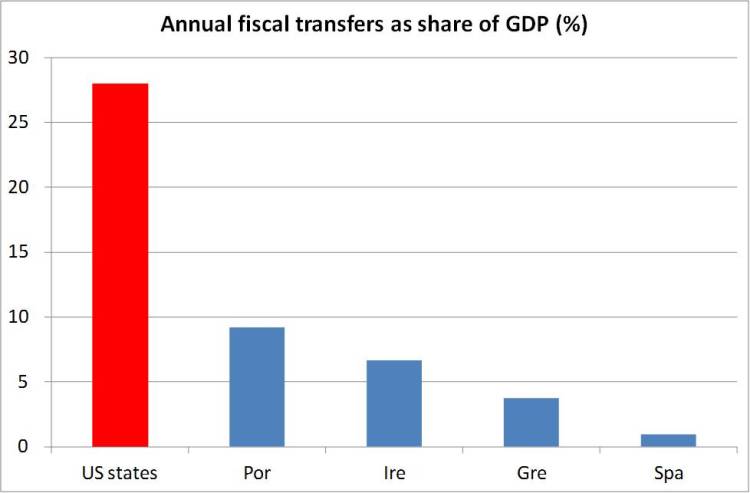

Those who wish the preserve the Euro project like the EU Commission, the majority of EU politicians and most capitalist corporations, recognise that the only way to do so is extend the process towards more integration. That means a ‘banking union’ so that all the banks in the Eurozone are subject to control by the Euro institutions like the ECB and not national government regulators. And, above all, by the establishment of a full ‘fiscal union’, so that taxes and spending are controlled by Eurozone institutions and deficits in one EMU state are automatically met by transfers from surplus states. That is the nature of a federated state like Canada, the US or Australia. These transfers reach 28% of US GDP compared to the controlled and conditional transfers under EU budgets and bailouts of less than 10% of one state’s GDP.

The Eurozone does not have such a fiscal union. Instead, after much kicking and screaming, the Germans and the EU agreed to set up some fiscal transfer funds, the EFSF and now the ESM. But these are not automatic fiscal union transfers; they are contingent on meeting fiscal targets in a Troika program and national governments can still set their own budgets. So there is growing opposition in Germany to shelling out cash for what they see as wayward countries who cannot get their public finances in order.

The IMF summed up the challenge for European capitalism in 2013: “2012 was a year of balancing on the edges of cliffs and precipices for Europe. 2013 needs to be a year of climbing mountains—doing the long and hard work of restoring competitiveness across economies to restore growth and making steady progress on completing the architecture of the monetary union.”

But can it be done? Is there time and will? Yes, austerity could eventually deliver the required reductions in budget deficits and debt. But already there have been years of austerity and very little progress has been achieved in meeting these targets and, more important, in reducing the imbalances within the Eurozone on labour costs or external trade to make the weaker more ‘competitive’. That could take many more years. Can the people of Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Slovenia and Ireland endure more years of austerity, creating a whole ‘lost generation’ of unemployed young people, as has already happened in Greece and will happen in Spain, Italy, Portugal and Slovenia?

The electorate is losing patience and is angry as the election turnout and vote in Italy shows and the events in Slovenia. The EU leaders and strategists of capital need economic growth to return quickly or further political explosions are likely. And yet, given the current level of profitability, that may take too long before, perhaps, the world economy drops into another slump. Then all bets are off on the survival of the euro.

My lecture is on You tube at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IaWHNaSRzmY&feature=youtu.be

A lot of people fell asleep.

new site of The Workers and Punks’ University (WPU): http://www.dpu.si/

“Cyprus may be required to privatize the Cypriot telecoms company, the electricity company and the ports authority.”…hmmm….is this why economists are promoting more government spending…..

seems to me government is being used as a leg for the publicly held corporations borrowings and for all the pension funds of the public and private ie. ALL retirement accounts that have a huge purchasing power….to be paid for by the individual tax return system….

Hi Michael. Currently watching the lecture on youtube, and I’m really enjoying it. But when you talk about the rate of profits as opposed to the mass of profits, in the U.S., I wonder: How can the mass of profits ever be diminished, i.e. how can a crisis occur, when the rate of profit is always positive (somewhere in the 20-30% range)? I hope that’s not a really stupid question and I’ve missed something blindingly obvious. Thanks, James.

The rate of profit is made up of the total mass of profit divided by capital advanced to buy constant capital (equipment, plant and raw materials) and variable capital (wages of employed labour). So the mass of profit (numerator) could fall but the rate of profit stays positive (but lower) as there is a stock of capital (denominator) to measure the lower mass of profit against. Most of the time the mass of profit rises but not as fast as the denominator and so the rate of profit falls. Only occasionally, just before a slump, does the mass of profit fall as in 2006-2008 in the US. But there is still a positive rate of profit as the mass of profit is not zero just lower.

Thank you for clarifying, I really appreciate this.

Interestingly, in the 1980s while the tensions between the various federal republics in Yugoslavia were still building up under the pressure of huge and unmanageable loans from the West and more openly festering nationalist discontent after the death of Tito, Slovenia — the richest of the republics — had a go at forcing Macedonia — the poorest — to settle accounts with it in dollars and not in dinars. They had to wait a few years before they got what they so witlessly wished for.

@Choppa Morph You’re right. Below is a shortened translation of the article published in the biggest newspaper in Slovenia, written by prof. Maks Tajnikar. You my find it interesting.

“A simple story of capitalism with some complications”

Maks Tajnikar (professor of economics at uni of Ljubljana)

At the end of the 1980s I wrote an article on the “exploitation”, which, however, has never been published. At the time, most (nationalist) politicians claimed that slovenes are “exploited” by the poorest federal republics of Yugoslavia and, therefore, it was necessary to become independent as soon as possible. I considered essential to explain that the claim of “exploitation” was wrong because the more productive Slovenia have great benefits from the single market, and that the transfers from richest Yugoslav republics to poorest ones in fact enabled the realization of these benefits. So many years later, in Eurozone,

the article could be publish providing that I would replace “Yugoslavia” with Eurozone, and Macedonia – let us add a little sarcasm – with Greece. I am sure that today the average German believes that Athens via Brussels exploit Germans, and that the average Greek opinion that Germany continues its World Domination plan from the WWII. Why do Europeans speak of “exploitation”? First of all, we must realize that the concept of “exploitation” is not part of any economic theory except for Marxist one. If any two manufacturers of the same product compete against each on a single market, the price for the product is formed on the average level of labor used in the production of these two manufacturers. Marx would say that the surplus value created by the work flows from less productive to more productive. The more productive manufacturer will get per unit of labor more than the less productive one. Marx says that it is nothing wrong with this. A similar transfer of the surplus value is going on also between two sectors, as it was shown by Marx in his famous transformation problem. The surplus value flows from labor-intensive to capital-intensive sectors. This simplified Marxist explanation gives the answer to the question why Europeans talk about “exploitation”. Differences in productivity in EU economies are more than twice and still growing. Therefore, a huge overflow of surplus value from less to more developed countries is going on within the Eurozone. The exchange of goods within the Eurozone makes possible the exchange between less-productive countries’s products for smaller quantities of more productive countries’ products. For the same level of earnings therefore the Greek, Portuguese, Spanish and Slovenian workers must work longer than German workers. Therefore, the single European market Euro undeniable benefits developed and especially those who can quickly increase the productivity of their work. It is clear why the United Kingdom has a problem with the EU: it could benefit only had the British be a part of the Eurozone. More developed countries also create oligopolies and monopolies in the single market; the rest are only sub-contractors and manufacturers with a lot of work. The gap in productivity and due to monopoly makes less developed countries too expensive and uncompetitive. If they want to keep up with their income, they must borrow. This increases the flow of money in the euro countries that are lagging behind, which creates excess demand in their markets and increases inflation. Slovenian companies every day are losing their competitiveness in the European single market, even if they do not lag behind in productivity and are victims of monopolies. Why do you think that all Slovenian exporters lower profits? The lag in productivity, production in sectors with high labor intensity, subordination to foreign brands and external borrowing Slovenia, makes them too expensive. This means that it is increasingly difficult to trade with, for example, Germany.

Single labor market – an illusion

Extrapolating the described processes would mean that, over time, less developed economies within the Eurozone will disappear, which partially confirms even the U.S.. But then, would not only apply to Slovenia and Greece would not be able to trade with Germany, just because they lack exported and have no income to pay for imports, but Germany would not be able to trade with them. Crisis is exacerbated by the introduction of a single European market in the field of labor and capital. If you defend the workers, because they affect the European labor market, or just because they are already on the edge of survival, after paying ‘European’ cost of capital to more developed countries, debt increases. Servicing the debt becomes even more expensive as higher labor costs in higher prices melt at lower productivity. If the German economy due to its superiority fails to pick up all the cream in Greek, Slovenian and Spanish market, then it picks up their banking. This is all completely legal! Then there is nothing unusual if the bankers for workers in European patients seem to be mere criminals.

It is an illusion that it is possible to stay together with the described tendencies. Of course you can say, come on, you can also increase productivity in Slovenia and become the market leader. But this is also an illusion, which is not justified by history. One Euro in European trade demands in Greece twice or three times as much work as in Germany. If this goes on as before, Greece will soon no longer be able to trade with Germany and the latter will not be able to benefit from the flow of surplus value from Greece. Greece will not be able to remain in the eurozone, Germany would not have interest in Greece in the eurozone. The less developed countries will be leaving the Eurozone, and the currency will end in a pile of dusty history.

All of this, of course, blame the Euro. If Germany and Greece still had the drachma and Deutsche Mark, Greece would simply devalue their drachma, thereby reducing all prices. If the devaluation is large enough, Greece with its cheaper products would again become competitive in the trade with Germany. Both countries would benefit. Germany would have a market to sell. German economists have calculated that the Greeks need to devalue by 37 percent, 30 Portuguese and Spanish 20 percent. But the PROBLEM is that Eurozone does not allow devaluations.

Therefore, erosion of the Euro is running faster than global warming.

Increasingly clear is that departures from the Eurozone will be the rule rather than the exception, if nothing will change. Greece’s departure would mean that it would have increased its debts in Euros, to at least some time should live only on its own product. A devalued drachma would accelerate exports and allow for growth. Level of living of an average Greek citizen would be decreased compared with the Germans, but not compared to other Greeks.

The longer will Europe torture Greeks with the present economic policy, the easier it will be for them to leave the Eurozone. Greek bankruptcy would cost Germany, German economists say, 80 billion euros. Because of the latter to the banks and credit rating agencies have been better off, if they require lower interest rates for indebted countries within the euro. BUT a financial world, in its role as a monopolist, which is stronger than the state and their unions, will never do it. It is true that profit motive is blind!

Too bad for the Eurozone that it does not allow devaluations. The most productive countries will have to pay significantly more to support the least developed ones within the Eurozone.

This can be done in different ways, but the amounts will have to be significantly higher than is currently the support from Brussels. It will demand both “brotherhood and unity”. If Greece will leave the Eurozone, it will do it for political reasons and not for economic benefits. Pressure on European politicians Greeks are disproportionate, unrealistic, arrogant and lofty. Politicians would not dare propose such measures in their own countries. It is a reminder that the Eurozone is nothing more than a simple story about capitalism with a few complications.

No mention of Goldman Sachs and its collusion with the rating agencies. I only wish that Marx wrote something about the activities of the usurious Banking Dynasties and the Sassoons’ drug Empire. My advice to Slovenia is to forget the gobbledegook Marxist claptrap and follow Iceland’s example. Don’t pay the Banks a shekel. Iceland’s economy is growing very well, not that it is mentioned in the Free Press.

Slovenia be warned: The Global Bankers’ ( New York, London and beyond), only interest is interest. Foolishly, Cyprus heeded the advice of the fiat currency alchemists and its indebtedness grows day by day. Slovenia your only salvation is following Iceland’s counter financial-terrorism model. For centuries an omnipotent parasitic clique has ruled the world. These obnoxious criminals must be thwarted.