War Within A War: The Rise & Fall Of FULRO, PT I

The Buôn Ma Thuột Rebellion

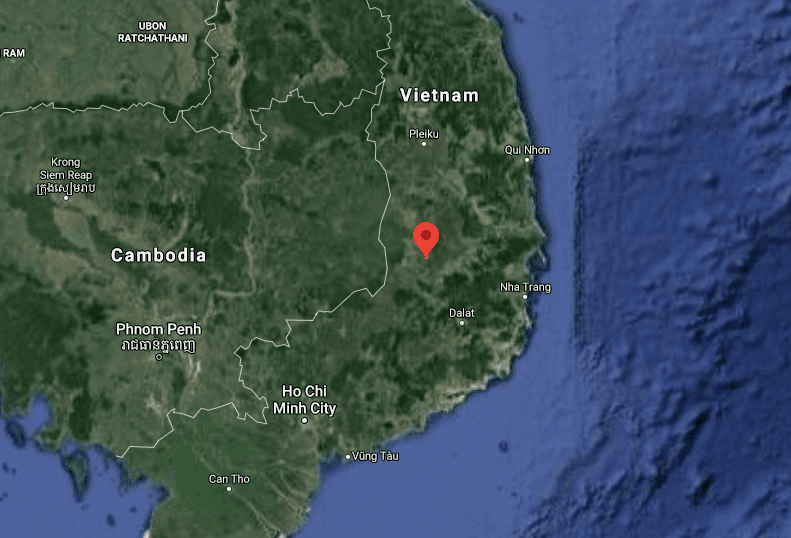

On September 20, 1964, American-trained Civil Irregular Defense Group (SID-GEE) troops based at Special Forces bases Buon Sar Pa and Bu Prang in Quang Duc province and in Buon Mi Ga, Ban Don and Buon Brieng in Darlac Province, on the Viet-Cambodian border turned on their South Vietnamese allies, killing dozens and disarming Americans on the bases.

From the Buon Sar Pa base, the rebels seized the radio station on Route 14 on the south-west outskirts of the town of Buôn Ma Thuột, and began to broadcast calls for independence for a variety of ethnic groups who had lost their homelands to centuries of Vietnamese incursions and settlement.

Tracy Atwood, an agricultural technician with the International Voluntary Service (IVS) was at Buon Sar Pa, and described how he was awakened by shouting, screaming, and shooting at around 1 am. (Quoted from Gerald Cannon Hickey’s Window on a War):

At the door he found himself face to face with several CIDG highlanders, one of whom shouted in English, “This is our night! We’re going to kill Vietnamese.” Atwood witnessed a highlander empty a clip of ammunition into the back of a Vietnamese interpreter. Atwood and the American team members were pushed into a room where Y Dhon Adrong, a Rhadé, came to assert that the camp had been taken over by FULRO. The aim of the revolt was to retake territory the Vietnamese had “stolen” from the highlanders, Cham, and Khmer Krom.

After the rebels left there was shooting outside. Team leader, Capt. Charles Darnell, reached the Bu Prang Special Forces team by radio and the commander reported that the Americans still had control of the camp but most of the Strike Force had gone to Trois Frontières to meet FULRO troops coming from Cambodia.

By 6:00 A.M. the shooting outside ended. The Vietnamese camp commander was tied to the flagpole, but all of the Vietnamese Special Forces team had been killed and their bodies thrown into the latrine.

Negotiations floundered between the rebels and the Army of Vietnam (ARVN), with the Americans, under direct orders from Gen. Westmoreland stuck in the middle.

With hostages- both Vietnamese and American Special Forces being held, including Col. John “Fritz” Freund, sent to control the situation- a military strike force was prepared to end the uprising, but a last-minute amnesty offer- brokered by the US- came from Saigon, and led to the agreement of surrender on September 27.

However, most of the group had already crossed the border to a former French base Camp le Rolland 15 kilometers across the border in Mondulkiri province- neutral Cambodia.

FULRO

The Americans had been caught off-guard by this short curious, but bloody rebellion. Unaware of FULRO and its leadership- a ‘bearded Cham’ was identified as the commander who took control of Buon Sar Pa. The NLF (Viet-Cong) were initially blamed, and French intelligence- Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage– were also suspected of having some involvement.

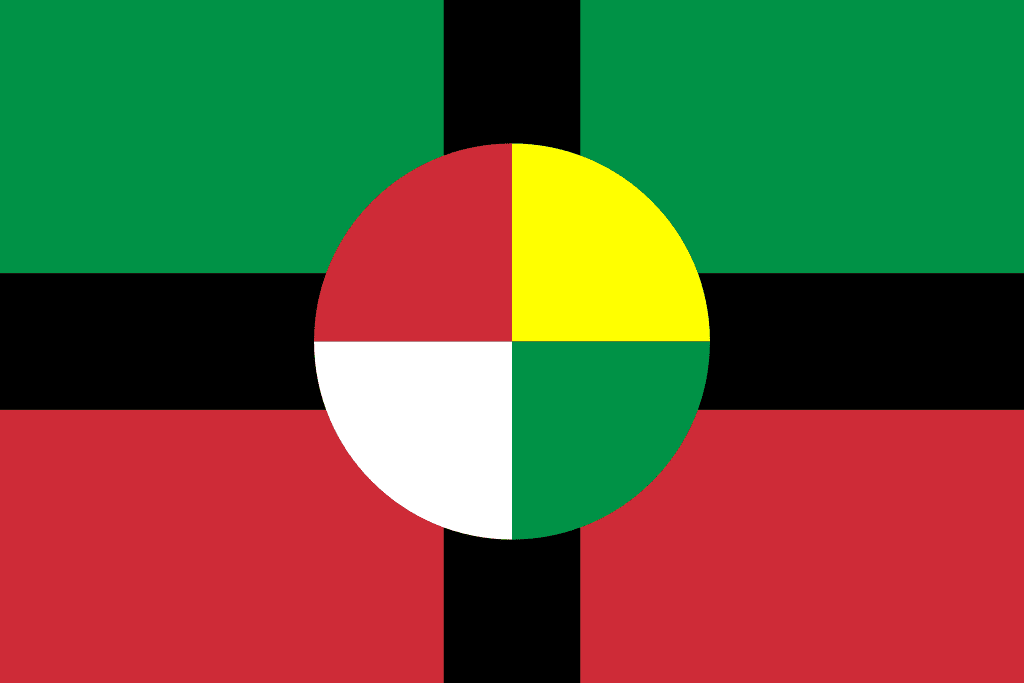

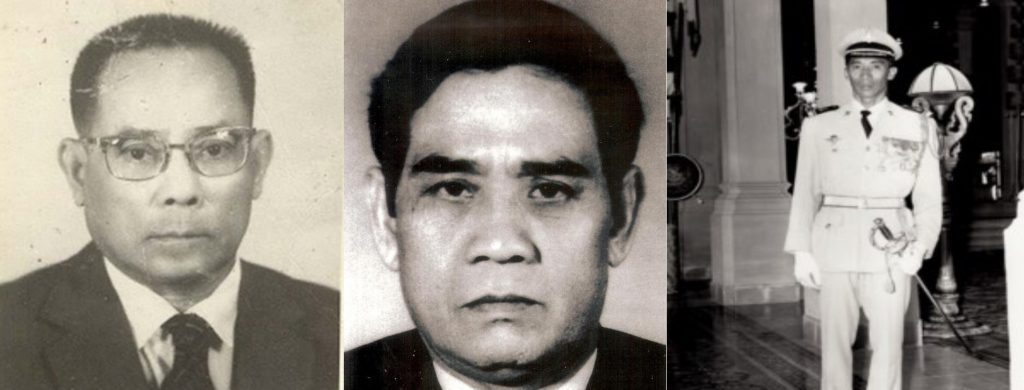

It soon transpired that Front unifié de lutte des races opprimées / United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races (FULRO) was a new political/paramilitary group led by Y Dhon Adrong, a former schoolteacher from the Rhade (E Da) tribe, two officers of the Royal Khmer Army; Lieutenant Colonel Y Bun Sur- Province Chief of Mondulkiri Province- a member of the Pnong tribe and an ethnic Cham Lieutenant Colonel named Les Kosem (both suspected of being French double agents), and Chau Dara, an ex-monk from Kampuchea Krom- South Vietnam’s Mekong Delta.

The roots went deeper into history, to French efforts to divide and conquer their colonial subjects, and the Nam tiến – the ‘southward advance’- that had seen Vietnamese expansion from the Red River Valley push down the coast since the 11th century.

As French Indochina began to crumble into nation states- North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos- small, but diverse populations with little in common, save their anti-Viet stance, began to unite- and soon make calls for self-determination.

The Montagnard

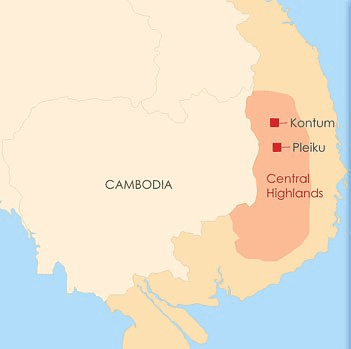

Assorted tribal groups once populated coastal areas of modern-day Cambodia and Southern Vietnam, before the expansion of early Khmer and Cham kingdoms sometime before the 9th century. They moved to the uninhabited mountains and jungles of the Central Highlands and remained in relative isolation until the French colonial era around one thousand years later.

Despite there being dozens of separate tribes of at least six distinct ethnic groups with unique languages based on three language groupings (Austroasiatic- the same branch as Mon-Khmer, Malayo-Polynesian- related to Cham and Malay and Kra-Dai- related to Thai and Laotian), the French labelled the population of the region Montagnard’; mountain people.

The French first used the local tribespeople for labor in coffee and rubber plantations, later, in a move unusual for the time, they granted minority groups limited autonomy, while such rights were denied to Vietnamese kinh elsewhere.

From the early days of French Indochina, the Central Highlands were viewed by the French as strategic areas that could be managed to control anti-colonial insurrections among the Kinh Vietnamese in the lowlands. The French administrator of Đắk Lắk- a somewhat colorful character named Léopold Sabatier (served 1914-26)- was one colonialist opposed to Vietnamese immigration to the highlands. Not only did he have a fondness for woman of the Rhade (also known as E Da) tribe- and at least one mixed race daughter- he also had a personal dislike for missionaries. Under his administration, a separate ethnic identity was created for the montagnards, along with acceptance of a tribal legal code.

In the 1930’s four major “tribes” in the central highlands were classified as ethnically different from the Kinh – the Bahnar, Sedang, Rhadé, and Jarai.

As Vietnamese revolts and insurrections continued, a French directive read “….to save this race, to disentangle it from all harmful foreign influences through a direct administration, and to tie these tribes to us … These proud peoples with their spirit of independence will provide us with elite troops, (serve) as safety valves in case of internal insurgency, and (act) as powerful combat units in case of external war”. An astute prophecy of what was about to befall peoples who wanted to be left alone.

After the French reclaimed their colonies after World War II, controlling the Highlands became vital. Ho Chi Minh had declared the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) from Hanoi in September 1945, with territorial claims over the three regions of Vietnam; Tonkin (north), Annam (central) and Cochinchina (south).

To counter this, in May 1946, the French high commissioner for Indochina Georges Thierry d’Argenlieu issued a decree making the central highlands a “Special Administrative Circumscription”, better known as the autonomous region for the Populations montagnardes du Sud-Indochinois or PMSI. Administered by a special French delegate, it consisted of the five upland provinces in Annam but excluded montagnard populations in the lower part of the territory as well as in Cochinchina, Cambodia, and Laos. Thierry d’Argenlieu’s strategy was to contain and if possible, roll back the DRV, without interference from Kinh Vietnamese, from the north or south.

DRV officials protested vigorously against both this and the French creation of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Cochinchina in the south. One French spokesman countered the DRV’s national claim to the highlands: “neither geographically, historically nor ethnically, can the highlands be considered a part of Vietnam”. DRV delegates reminded the French of Alsace-Lorraine.

Despite efforts to keep the PMSI free from Vietnamese expansion, in 1949, the French finally allowed the ‘autonomous’ Bao Dai government in Saigon to assert its “eminent rights” over the highlands. However, the French Associated State of Vietnam had to recognize the “free evolution of these populations in relation to their traditions and customs”.

To further delegitimize the Vietnamese claims over the area La Domaine de la couronne du pays montagnards du Sud (The Crown Domain of the Southern Highlander Country) or PMS was created. Although the French nominally recognized Vietnamese sovereignty over the highlands, they maintained a statut particulier for the highlands because of “special French obligations” and continued to direct the PMS through their special delegate, a Frenchman, not a Vietnamese representative of the Associated State.

In May 1951, Bao Dai signed a law promulgating the creation of a “special regulation” designed to provide more highlander participation in local affairs all the while reaffirming the “eminent rights” of Vietnam over this territory. However, Vietnamese national control over the central highlands remained incomplete until the French withdrew in 1954.

French efforts to counter communist-friendly nationalism led to efforts to build an educated anti-Viet Minh class among both the Kinh Vietnamese and Montagnard youth.

This led to hundreds of young men from various tribal groups coming from across the highlands to study at Collège Sabbatier in Ban Me Thuot in what became the common upland language, Rhadé, (E Da ) closely related to the Chamic language.

This lingua franca appears to have created some cohesion between groups that were previously unique, save for geographic location and minority status. Marriages between different groups were reported- unthinkable in previous times- and a new socio-political identity under a better educated leadership began to form.

Saigon, of course, had other plans. “The white man has a certain mystique for the highland people that the Vietnamese do not have.” One South Vietnamese general was reported to have said, following the American intervention and de-escalation of the rebellion at Buôn Ma Thuột in 1963.

The Cham

Another minority group- the Cham, were also given tacit support by the French to counter Vietnamese nationalism. The Kingdom of Champa, once a rival the Angkor Empire, had been lost over the centuries to the Vietnamese, and Emperor Minh Mang annexed the last ‘rump state’ remaining Champa Kingdom in 1832.

Over the centuries, Cham refugees- many following Islam, while others were Hindu- had mostly been welcomed in Cambodia, and had a sizeable presence at the time of Independence in 1954. In the vacuum that was left by the French as they left Indochina, hopes for a new Champa state rekindled, and a struggle against all Vietnamese- both North and South began.

Renowned scholar of Cham history, Po Dharma (born Quảng Văn Đủ) was an early member of FULRO. In December 1970, he was seriously injured fighting North Vietnamese in Kampong Cham and later moved to France and continued his studies.

The Khmer Krom

National dissident groups had formed within Cambodia too- well-known example being the Khmer Issarak who fought against the French from bases on the Thai and Vietnamese borders (and also formed occasional alliances with Viet-Minh communist guerrillas), which morphed into the anti-Communist and anti-Sihanouk group the Khmer Serei in the late 1950’s under Son Ngoc Thanh.

Thanh was from Kampuchea Krom- former Cambodian lands in the Mekong Delta which had been slowly taken over by Vietnamese encroachment and settlement over the years- becoming Cochinchina. On June 4, 1949 the French President Vincent Auriol signed the accord reincorporating Cochinchina to Vietnam. This was done without consulting the Khmer Krom population.

Ethnic Khmer Krom fighters also began a campaign against forced Vietnamization- such as being forced to take Vietnamese names, and forbidden to study in Khmer language- and began to organize movements for separate statehood.

The Coming Together

Following the withdrawal of the French after defeat at Dien Bien Phu, and the dissolution of the Indochinese Federation, four nation states emerged; The Kingdom of Laos, The Kingdom of Cambodia, The Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North) and Republic of Vietnam (South). As these four headed towards wars that would last for decades, minority movements were also forming inside Cambodia and the Vietnamese Highland border areas.

They included:

The Khmer Serei founded by Dr. Son Ngoc Thanh in 1958

The Khmer Con Sen Sar, or Khmer White Scarves movement, a semi-mystic, semi-military group, founded in 1959 by a monk named Samouk Seng.

Front de Libération du Kampuchea Krom- Front for the Liberation of the Kampuchea-Krom, or the FLKK, led by Chao Dara.

The Champa Liberation Front, founded in Phnom Penh in 1960 and led by Royal Cambodian Army officer Les Kosem.

BAJARAKA, which stood for four main ethnic groups: the Bahnar people, the Jarai, the Rhade people, and the Koho people formed on May 1, 1958, under Y-Bham Enuol. It soon split with another movement Front de Liberation des Hauts Plateaux, Central Highlands Liberation Front or FLHP.

These groups were introduced, under the blessing of the Cambodian state- and possibly with clandestine French influence- which led to the formation of the Front unifié de lutte des races opprimées (FULRO) or United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races.

The High Council consisted of Chao Dara as the Chairman of the Assistant Council, Les Kosem as the Chairman of the Central Committee and Y-Bham Enuoil as the Chairman.

The FULRO Montagnard movement was divided into two groups:

A peaceful resistance faction, under the command of Y-Bham Enuoil, was to lobby the United States to put pressure on the government of the Republic of Vietnam to allow the FULRO Montagnards to return to Vietnam as a legitimate political movement.

An armed wing under the command of Y Dhon Adrong was trained to use force in the fight for an independent nation.

The Cambodian Safe Haven

By 1964, the more radical Montagnard group the FLHP had established a base, with the blessing of Phnom Penh, at a former French military site Camp le Rolland in Mondulkiri province, 15 kilometers from the South Vietnamese border. It was here that the FULRO rebels from September 1964 retreated to, and where they continued to recruit and train fighters from the ethnic communities in Northeastern Cambodia.

Sihanouk hosted the “Indochinese People’s Conference”, in Phnom Penh in early 1965, this time an official FULRO delegation attended, headed by the popular Y-Bham Enuol. Y-Bham’s address reviewed historical friendly relations among the highlanders, Cham, and Khmer and after declaring that the movement were now struggling with the “American imperialists” and “South Vietnamese colonialists,” he lavished praise upon “Samdech Preah Norodom Sihanouk Varman.”

FULRO then published anti-South Vietnamese propaganda that attacked the Saigon regime and applauded Cambodia for its support.

The organization also released maps showing that their aims; Montagnard and Cham independence within a new Champa kingdom compassing areas of Ratanakiri and Mondolkiri provinces in Cambodia and the Central Highlands of Vietnam. Kampuchea Krom would be returned to Cambodia.

The American Conundrum

Yet, FULRO forces along the Cambodia-Vietnam border were still battling Viet-Cong and NVA regulars. The Americans clearly had a classic conundrum on their hands- like much of the Vietnam war there was no clear black or white, good Vs. evil, but a complex web of history and powerplay that Washington could not, or would not, truly understand.

Important factors for the US giving FULRO limited support were (among others):

- The Highlanders were western friendly, and still had loyalties to the French, with many converted to Christianity by American missionaries in the 1930’s. Attempts and offers had been made by Hanoi to appease them in a ‘united Vietnam’ but had for the most part been rejected- there was very little communist sympathy.

- The Cham leaders were well ingrained into the Cambodian army of Sihanouk’s Cambodia, yet as outsiders, had possibly less loyalty to the state. As the prince’s behavior became more erratic and seemingly friendly towards the communists, a pro-American faction within the armed forces would need them.

- The Khmer Krom irregulars were already experienced guerilla fighters and had very little to lose.

- Control of eastern Cambodia and the Central Highlands would be crucial to stemming the flow of men and munitions coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail into Southern Vietnam

- Montagnard local knowledge, Cham contacts in the Khmer Armed Forces and Khmer Krom manpower would help achieve the goals of cutting off DRV supply lines.

Likewise, potential problems included:

- South Vietnam, as an ally, would not tolerate dissent within its territory. The 1964 uprising had split the RVN-US- Montagnard relationship, and trust between all sides was strained.

- Cambodia, although neutral, was under Chinese influence, and appeared to be turning increasingly pro-Hanoi and anti-Saigon. By using FULRO to Cambodian advantage, it was possible that the lost provinces of Kampuchea Krom- still a bitter pill for the Khmer people- may have been partially offered as return for a secret Cambodian-DRV alliance against South Vietnam. A real danger was that the Cambodian government could use FULRO as proxies to aid Viet Cong operations in the heart of South Vietnam, while still keeping the regular Khmer forces in barracks and remaining neutral.

- Ho Chi Minh had laid down various ‘nationalities policies’ chinh sach dan toe since before his rise to power, and there was the risk that inaction by the Americans would cause some influential FULRO members to split and join the Viet-Cong based on promises given by Hanoi.

- Saigon had broken several agreements with the Montagnard and continued to encroach and settle the Central Highlands. Provocation from either side could have led to a ARVN military campaign against FULRO. The proximity to Cambodia may easily have led to border violations and drawn Cambodia into the wider war.

- Tensions were already running high in Saigon. The Buôn Ma Thuột rebellion came towards the end of larger civil unrest in South Vietnam- the Buddhist crisis from May-November 1963 (with the infamous self-immolation of Thích Quảng Đức)- a dispute between Catholic elite and the Buddhist majority- led to the deposition and assassination of President Ngô Đình Diệm. Any further sectarian or ethnic crises would almost certainly topple the fragile and unpopular military regime that saw five different heads of state from 1963-65.

Instead, Washington chose to raise the FULRO issue with Saigon, while conveniently ignoring the bases in Cambodia. The Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), from 1964, began recruiting ethnic minority soldiers from across Vietnam for Mobile Strike Force Command, known as Mike Force- an elite unit used for reconnaissance, rescuing downed airmen and counter-guerilla operations.

At the same time North Vietnamese NVA regulars had moved several battalions into the Central Highlands, just as American forces were building up following the first Marines landing at Da Nang on March 8, 1965.

The first major engagement between the Americans and North Vietnamese took place in November 1965 in the Ia Drang Valley- close to the Cambodian border in the Central Highlands. The war- seen as between outsiders- was now firmly in the Montagnard’s backyard. In 1963 there were 16,300 US service personnel in Vietnam, by 1965 there were 184,300.

Part Two: The Decline- 1965-92

*All is written to be as accurate as possible, but some sources differ and names, dates and events may conflict. H.S.

Sources include: Gerald Cannon Hickey- Window on a War, Khmer Thnaot, University of Quebec, New York Times, Dagar Foundation