Correction: This story originally contained the incorrect year when the Battle of the Bulge began. Also, some photo captions misspelled Arthur Bonifazi's last name. They have been corrected.

“Love, Patty.”

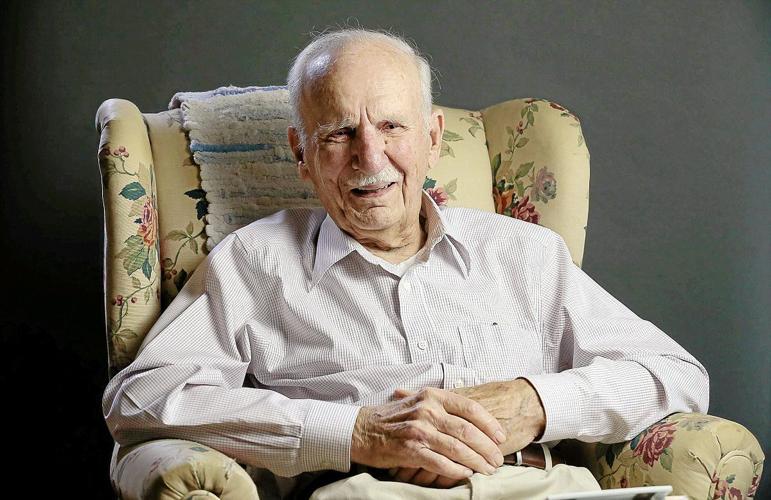

Arthur Bonifazi can’t say for sure how many times he read and re-read those words — or a variation of them — at the end of a letter.

But whatever the number, it could never be enough.

Thousands of miles from home, those written reminders of his sweetheart Patty Shurley’s undying affection helped him remember what he was fighting for.

“She still lays claim to saving my life,” Bonifazi, 91, said, recalling one letter he received while in Dusseldorf, Germany, near the end of the war in Europe.

People are also reading…

- Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Price Tower sold to Tulsa firm that revitalized Mayo Hotel

- Local high school basketball players die in Kansas crash

- City leaders provide details on weekend shooting, insist downtown Tulsa remains safe

- Oasis Fresh Market planning second grocery store location in downtown Tulsa

Sitting in a chair outside a building to read it, he had just finished it and gone back inside, when he heard the explosion.

It was an artillery shell. It had hit the chair where he’d just been sitting, blowing it to pieces.

Today, 69 years into their marriage, she sometimes reminds him of it.

“She says if she’d written one more line, I’d have gone with the chair,” Bonifazi said with a chuckle.

Immigrant’s son

A native of Dubuque, Iowa, where his father had settled after emigrating from Italy, Bonifazi was drafted into the Army Air Corps in 1943.

While stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey, he and his fellow troops often received USO passes to go to New York shows. One day, a buddy invited him to see the original “Oklahoma!” on Broadway.

But Bonifazi declined. He already had plans for an evening at the Ringling Brothers circus.

Imagine his surprise, he said, when he learned the next day that he was being sent to Oklahoma. He was transferring to Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma City.

“I didn’t know if that was punishment or what” for not going to the show, he said, laughing.

If it was punishment, it worked out in Bonifazi’s favor. It was at Tinker that he began dating Shurley, who worked at the base.

They hadn’t been together long, though, when word came that they would have to part.

Bonifazi was being transferred from the Air Corps to the Army. A year and a half after he was drafted, he was going overseas to join the fight.

“Patty wanted us to go ahead and get married,” Bonifazi said. But feeling it wouldn’t be fair to her, he decided against it. If he didn’t come back, he didn’t want her to be left a war widow.

So they would settle for writing.

Shipping out for England via the Queen Mary, Bonifazi would serve with the 302nd Infantry Regiment, 94th Infantry Division, which would eventually be assigned to the 3rd Army under Gen. George S. Patton.

Not long after they arrived, the 94th moved on to France in September 1944 and into the Brittany region.

A long way from giving up

Bonifazi remembers his first night in a combat zone, German flares lighting up the skies.

“They loved to shoot those flares,” he said. “They could see us, but we couldn’t see them.”

The next morning, as a patrol leader, he went to check on his men, who were huddled in their foxholes.

He was in for a big surprise.

Yelling to the guy on the far end, “I asked ‘Who’s in that hole next to you?’ ... and a German soldier popped up out of it,” said Bonifazi, chuckling at the memory.

The German, who had joined them sometime during the night, had no fight left in him. He just wanted to give himself up, Bonifazi said.

Nazi Germany as a whole, though, was still a long way from giving up.

In mid-December 1944, the German counteroffensive that would become known as the Battle of the Bulge began.

“There was so much artillery fire. I don’t know how we came out of that alive,” Bonifazi said.

The worst part, though, was the cold. That winter was one of the worst Europe had experienced in decades.

“I was born and raised in Dubuque; that was cold to begin with,” Bonifazi said. “This seemed like it was twice as cold.”

Taking care of your feet was vital. Frostbite and trench foot were serious and all too common among the troops.

Bonifazi remembers shivering in his foxhole, “feeling like I had to get those shoes off and try to get my feet warm.”

He took his shoes off, he said, and hung his socks up to dry.

If he got captured, Bonifazi recalls thinking, at least it would mean going someplace warmer.

The unit was fighting throughout this time, and after the Bulge, when it resumed advancing, the opposition was still intense.

Death was all around, Bonifazi said.

“You’d see one of your guys laying in the mud dead — they wouldn’t even let us pick him up. They said the medics would get him.”

Among the many fallen soldiers he saw, he remembers one especially well — a guy from his company whom he knew. Bonifazi was catching a ride atop a tank when he saw the body lying off to the side.

“I got his Bible off of him,” he said. “I eventually brought it home. I carried it with me for a long time.”

There were lighter moments, too.

Once, while manning an outpost by himself, looking out across a river, Bonifazi suddenly felt a warm breath on the back of his neck. Freezing for a second, he grabbed the receiver to the outpost phone and swung it, trying to hit whoever was behind him.

He was greeted by a slightly bemused “moo.”

So focused on the river, he said, he hadn’t noticed one of the local cows sauntering up behind him.

Over the next few weeks, German forces were gradually worn down and began retreating. The 94th kept in pursuit, taking many prisoners as they went.

“Near the end of the war they were glad to surrender,” Bonifazi said.

Letters

Patty Shurley, who grew up in Sallisaw, started at Tinker Air Force Base after Bonifazi was already there.

“I remember somebody saying we were going to get a new girl Monday,” he said. “That was Patty.”

It didn’t take long for the new girl, who worked in the control room, to catch Bonifazi’s eye.

“One day,” he recalled, “I got up the courage to get my friend to ask Patty if she’d be interested in going to a basketball game with me. She said, no, she was going dancing. ... But I didn’t give up.”

His persistence was rewarded.

After he was called away to the war, their bond by then cemented, Bonifazi and Shurley wrote to each other almost daily.

An attractive brunette, Shurley could’ve passed for one of the era’s pin-up girls (she was “Miss Tinker Field” at one point). Once, when her photo appeared in a military publication, she began getting letters from all over from young servicemen.

Shurley felt it was her duty to answer them all and began corresponding regularly with some of them. Just hearing about her days, as mundane as she felt they were, seemed to lift their spirits.

But her heart, along with the bulk of her spare time and stationery, still belonged to Bonifazi.

Dusseldorf

Later in March, Bonifazi’s unit crossed the Rhine River.

Their course would take them eventually to Dusseldorf, where they would remain for the next few weeks.

One of Bonifazi’s memories from Dusseldorf was meeting for Mass one Sunday in a chapel.

The chapel was connected to a hospital that had been partly destroyed by bombs. But there was enough of it left for a service.

One thing was missing, though, Bonifazi said.

“The priest didn’t have an altar boy — I guess all of them were in the Army.”

So Bonifazi stepped in.

He might not have looked the part, dressed in his Army uniform, rifle on his shoulder. But afterward, he said, one of the nuns did compliment him on his Latin.

Bonifazi was still in Dusseldorf when the war in Europe ended in May 1945.

Part of four campaigns with 209 days in combat, the 94th had more than distinguished itself. It would receive a Presidential Unit Citation for its contributions.

He’s not sure when, but Bonifazi remembers Patton coming and speaking to the division and “thanking us.”

With the war over, Bonifazi’s main duty was helping keep order in Dusseldorf.

Priority No. 1, he said, was going house to house collecting any kinds of guns.

Bonifazi kept a German Luger pistol he confiscated. But he ended up trading it to a guy in his company who had his heart set on one.

Bonifazi believes he got the better deal in return — a beautiful triple-barrel shotgun, which he boxed up and sent home for his mother to keep for him.

Trading was also common with the German residents, for whom cigarettes were in big demand.

“I didn’t smoke,” Bonifazi said, “so it was easy for me” to trade his Army-rationed cigarettes. His best deal was a nice camera with a bellows that some Germans gave him for his cigarettes.

Along with items he traded for, Bonifazi took home enough war-related memorabilia to stock a small museum. But several years ago, his home was burglarized. The most valuable items were stolen, including the shotgun.

“It was a great shotgun,” he said, still sorry for the loss.

Reunited

Discharged in January 1946 as a first sergeant, Bonifazi sailed for home on a Navy ship.

He’ll never forget his arrival in New York and first sight of the Statue of Liberty.

“They deliberately went by and then turned around, so the guys on the other side of the ship would have a chance to see it, too.”

“It kinda made you cry,” Bonifazi added, his own eyelids reddening. “After a year and half, you finally see something that you recognize.”

An even better sight was waiting for him in Oklahoma.

Connected only through their letters for all that time, he and Patty Shurley were reunited in the flesh. They married in Oklahoma City shortly after his return.

The couple would go on to raise seven children together. Bonifazi graduated from Oklahoma A&M with a degree in mechanical engineering. He would eventually have his own firm in Tulsa.

Reflecting on his military service, he said: “People of this generation should really do all they can to keep the peace. ... I had a year and a half of good times (before going overseas). But war is really hell.”

He saw too many men lying dead in the muck to ever think otherwise.

“When you see that,” he added, “you’d think ‘Who in the devil wants to start a war?’ ”

Tim Stanley 918-581-8385

Please direct inquiries about this series, or the veterans who have been featured, via email to bobby.marshall@tulsaworld.com.