In March 2020, Benjamin Espinoza Zavala saw an entire floor of his small hospital in Guanajuato, central Mexico, converted into Covid-19 wards. The hospital’s need for oxygen soared.

Deliveries from CryoInfra, part of the Grupo Infra group, occasionally slowed to once every couple of days, and he had to buy in extra to cover the sudden gaps in supply. Prices increased.

In January, the hospital built an onsite oxygen generator plant – also known as Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) plants – at a cost of 3.5m pesos (£125,000). It could supply the entire hospital and has already paid for itself in savings. The PSA equipment delivers 93% pure oxygen from air, as opposed to 99.5% purity from liquid oxygen suppliers.

The World Health Organization, Unicef and the World Bank have been helping hospitals in low- and middle-income countries build such onsite oxygen plants.

Grupo Infra noticed that orders had fallen. “Top executives, directors, administrators, doctors [from Grupo] came to the hospital to see the plant,” said Espinoza, general manager of the Celaya SA de CV Medical Specialties Centre in Guanajuato. “The administrators who visited were very kind, polite. We were on good terms.”

Then, in June, Grupo Infra’s lawyers told Espinoza’s hospital it had breached its contract by installing the plant and faced a hefty penalty. “If we stopped buying from them, we faced a fine of 1,300,000 pesos [£47,000].”

Espinoza objected, arguing that the hospital had never stopped buying the company’s oxygen, only reduced its order. “The contract doesn’t say anything about the amount we are obliged to buy,” he said. Grupo Infra later wrote to him, increasing the penalty to more than 10,000,000 pesos (nearly £400,000). He has been negotiating with the company since June, but no agreement has been reached.

Grupo Infra and another oxygen supplier, Praxair Mexico – who together control 70% of Mexico’s medical oxygen market – have been accused of spreading fear, doubt and misinformation, deterring hospitals from switching to cheaper and more convenient PSA plants and threatening legal action if they did, according to an investigation.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism claims that the companies sent letters to Mexican hospitals that contained misleading claims about the safety of the plants.

Grupo Infra said its actions were based on Mexican regulatory requirements and industry documents on the use of PSAs, oxygen quality and transport requirements. The company said it was not aware of legal action taken against any hospital for installing PSA equipment.

Praxair, and its German owner Linde, which had $27bn sales in 2020, did not respond to requests for comment.

Mexico has the world’s fourth highest Covid death toll – 253,000 to date. Researchers believe the true figure could be nearly three times as high, as testing numbers are low.

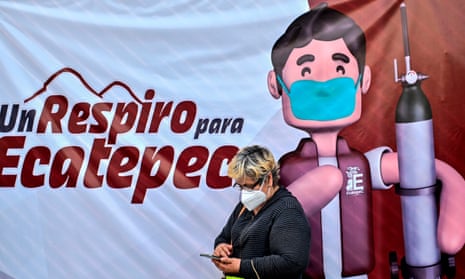

Demand for oxygen has soared. In December 2020, cases in Mexico City overwhelmed hospitals and the national guard was deployed to protect oxygen delivery lorries.

Dr Marta Hernández Vázquez*, director of a hospital in Michoacán, installed a PSA plant in October 2020. Her facility treated many patients with respiratory issues and she needed up to 40 cylinders a month, costing 30,000 pesos (£1,000). She said she was tired of reliance on Grupo Infra and wanted a convenient and more affordable supply. The PSA plant meant the hospital needed fewer cylinders a month from Grupo Infra.

On 6 October, Hernández received a letter from Grupo Infra’s lawyer warning that it would take away its cylinders if the hospital used them at the same time as onsite-produced oxygen. It also claimed such plants “put human life at risk”, and that PSA plants did not comply with regulations, produced lower quality oxygen than Grupo Infra, and could cause fires and explosions.

Hernández sent the letter to Ignacio Andrade, a biomedical engineer at HC Promedical, who imported the plant from the US. “The first time I read it, I said, ‘I don’t want to sell these [plants] any more, because if they’re telling the truth, we’re gonna kill some people’,” Andrade said. But the US manufacturer, AirSep, assured Andrade that the letter’s arguments did not reflect the truth.

Jim Stunkel, vice-president of Assist International, an NGO building oxygen plants worldwide, said: “I can easily say it appears obvious that the points of the letter are intended to block the implementation of PSA plants.”

Dr Paul Sonenthal of another medical NGO, Partners In Health, added: “What will put human life at risk is if a compressed gas supplier were to abruptly ‘take away its equipment’ from a hospital in the midst of a pandemic.”

Praxair Mexico made similar claims in a letter to at least one hospital. It said that using an onsite oxygen plant was breaking the law and the hospital’s contract with the company. If it continued, Praxair would stop supplying its oxygen. The letter said oxygen from PSA plants could aggravate respiratory conditions and cause “potential death”.

Grupo Infra told the bureau it did not recommend PSA equipment use in hospitals that have anaesthesia equipment, high-flow ventilation and hyperbaric chambers. “In our opinion, PSA equipment is suitable for hospitals located in hard-to-reach areas where the supply of cryogenic oxygen is complex. These hospitals are usually focused on primary care and do not have intensive care equipment that, due to the configuration of the medical equipment manufacturer, could require oxygen with 99.5% purity.

“It is important to mention that, in accordance with the current regulations … the minimum quality requirements that national and international products must satisfy, are the following: ‘Oxygen 93% grade (FEUM Pharmacopoeia) is used exclusively for respiratory therapies. Do not allow the use in anaesthesia processes and equipment, high-flow ventilation to patients and hyperbaric chambers’.”

Hernández has continued to use the generator plant. She said she believed the letter’s contents were unfounded and it was aimed “to pressure me or scare me”. “We are very happy with the results [of the plant],” she said. “It is a comfort that we generate oxygen here.”

Andrade believes that some of at least five other hospital clients who received the same letter have pulled out of installing PSA plants.

Leith Greenslade, coordinator of the Every Breath Counts Coalition, said: “To receive a long letter filled with legal jargon, serious medical claims, and highly technical engineering and infrastructure terms is meant to bamboozle the reader into submission.”

The coalition is writing to hospitals and government officials in Mexico to clarify that generator plants, and the oxygen they make, are safe.

Mexico needs more than 100,000 cylinders a day, just for Covid-19 patients, as cases rise.

“This situation with Grupo Infra worried me more than the drugs we ran out of because the fine was very large,” said Espinoza. He does not regret installing the oxygen plant. “The pandemic came and changed the ballgame for everyone when it comes to costs.”

* Name changed

Additional reporting by Rosa Furneaux