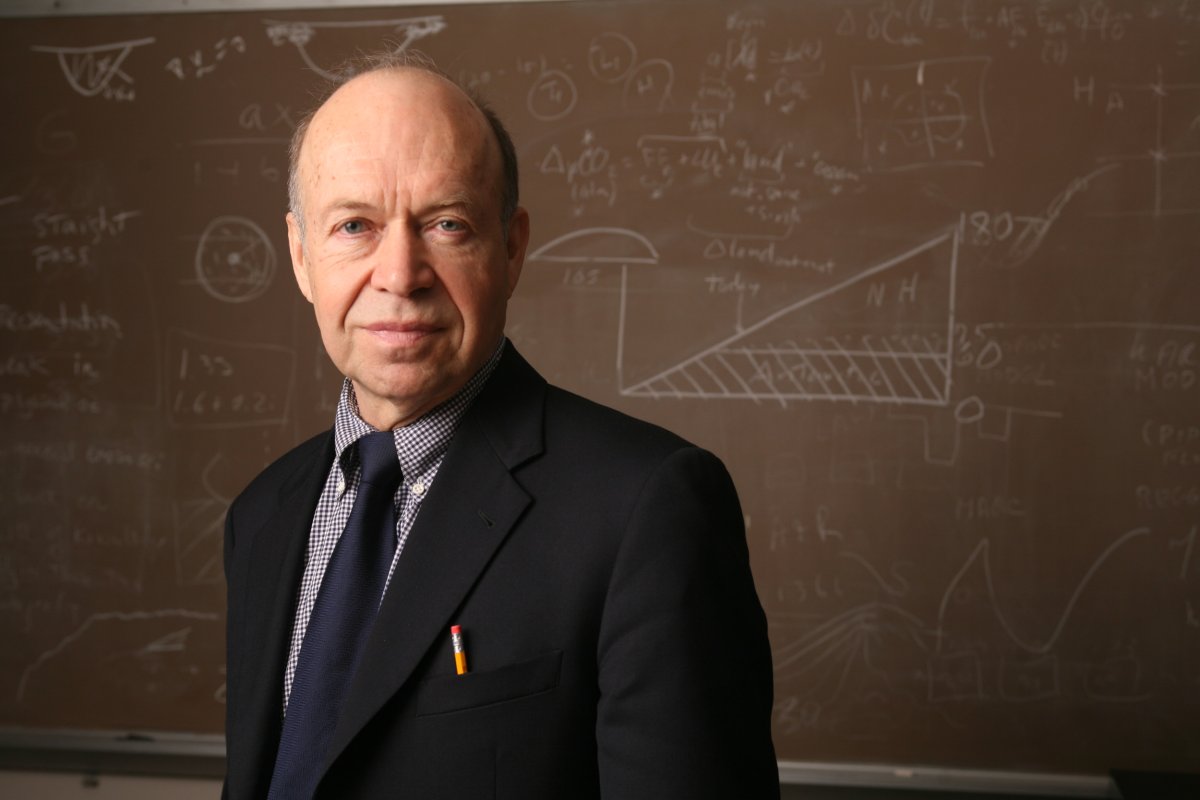

James Hansen became the face of climate science 35 years ago with high-profile appearances before Congress, calling attention to global warming. Hansen is widely respected for his research on greenhouse gas emissions and warming, and as director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies at the time, his words carried additional authority. But Congress did not act on climate change in the '80s or the '90s.

Hansen stepped up his warnings, urging immediate reductions in the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change and joining climate protests. He even got arrested during acts of civil disobedience outside a West Virginia coal mine in 2009 and near the White House in 2011.

Now an adjunct professor at Columbia University's Earth Institute, where he directs the Program on Climate Science, Awareness and Solutions, Hansen is issuing a new warning about climate change—as well as a controversial call for action.

Hansen and 17 co-authors argue in a new peer-reviewed paper that warming is accelerating beyond what many climate models show, and that cuts to greenhouse gas emissions—while urgently needed—will not be sufficient to avoid very dangerous levels of warming. He thinks a form of planet-wide geoengineering to block some of the sun's incoming rays will probably be needed.

"Highest priority must be to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as fast as practical, but that will not restore Earth's energy balance in less than several decades, at the best," Hansen told Newsweek in an email exchange. "In order to avoid large sea level rise and global chaos, we need to cool off the planet."

Hansen's conclusions about rapid warming and his embrace of geoengineering intervention in the climate put him at odds with many other leading climate scientists.

"I have the greatest respect for Jim's contributions to our science, but I think he's misguided on this," climate scientist Michael Mann told Newsweek. Mann, who serves as presidential distinguished professor at the University of Pennsylvania, directs the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media. He disagrees with the premise of Hansen's paper—and especially the recommendations for solar geoengineering.

"I'm deeply troubled by it," Mann said. "This is policy advocacy and dangerous policy advocacy, in my view."

Mann was a lead author on part of the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, the influential 2001 report that summarized the state of climate science.

Oxford University Physics Professor Raymond Pierrehumbert was also a lead author for the IPCC report and is a vocal critic of solar geoengineering. In an email to Newsweek, Pierrehumbert put things bluntly: "Jim has gone off the rails on this," he wrote.

Solar Radiation Management

In the paper Global Warming in the Pipeline, published Thursday in the annual journal Oxford Open Climate Change, Hansen laid out his argument for a form of geoengineering called Solar Radiation Management, or SRM, which can take a few different forms.

"The most innocuous SRM is probably spraying of (salty) sea water into the air by autonomous sailboats," Hansen said in an email to Newsweek. Robotic watercraft sending plumes of seawater skyward would help to "seed" the formation of low-level clouds. The clouds would then shade more of the ocean and reflect sunlight back toward space.

Another more controversial method involves high-flying aircraft injecting large amounts of aerosols into the stratosphere, forming a layer of tiny particles to bounce back some of the sun's rays.

"Nature has provided some nice tests, such as the Pinatubo volcanic eruption," Hansen said. That massive 1991 eruption in the Philippines sent so much particle matter into the upper atmosphere that it temporarily overcame the greenhouse heating effect and caused some global cooling, something Hansen and his NASA colleagues documented at the time.

He joined other scientists in an open letter in February urging more study on the effects of SRM. A report from the United Nations' Environment Programme this year also called for further study, and the U.S. government launched a review of geoengineering programs this year but stopped short of funding research.

Many other scientists warn that such tinkering with the atmosphere is fraught with unintended consequences for human health, weather systems and agriculture, and that any such program could not be fairly governed at the global scale.

In 2022, more than 60 climate scientists and policy experts launched a global initiative calling for an international non-use agreement on solar geoengineering, and hundreds of scholars around the world have now joined them.

Pierrehumbert at Oxford is part of the effort to ban deployment, public funding and outdoor testing of solar geoengineering, and he rejected Hansen's idea that SRM could be used in a temporary fashion to buy time for future carbon drawdown from the atmosphere.

"There is no such thing as 'temporary' use of solar geoengineering," Pierrehumbert said, adding that an SRM program would have to be maintained over a long term to avoid a rapid bounce-back of warming if its solar shielding should stop.

"Any suggestion that one could rely on solar geoengineering as a 'buying time' measure is fallacious, and just distracts from the necessary work of decarbonization," Pierrehumbert said. Solar geoengineering critics worry that a tech fix promising a cooler Earth would become an excuse to delay efforts to end the use of fossil fuels.

Despite those warnings, solar geoengineering programs have attracted major funding at some leading research universities.

University of Chicago professor David Keith is among the leading experts on this form of solar geoengineering. Keith is the founding faculty director of the Climate Systems Engineering initiative the university launched this year to explore ways to head off the effects of rapid climate change. Before that, he led the development of the Solar Geoengineering Research Program at Harvard University.

In an interview with Newsweek, Keith emphasized (as he regularly does in presentations) that solar geoengineering alone is not a climate solution.

"It's at best a weak supplement to what we must do to cut emissions," he said. But Keith defended his research on the benefits of solar geoengineering and challenged critics to be more specific and rigorous in exploring the risks they are concerned about. Further, he argued that the risks of solar geoengineering must be weighed against the risks of continued warming without it.

"There's no risk-free answer," he said. "The question is which is less risky."

For example, Keith said SRM would likely involve the injection of sulfur particles into the high atmosphere, cooling things to a point that would save lives from extreme heat. But sulfur particles are also air pollution, which could harm human health and damage the ozone layer, likely contributing to deaths. Those trade-offs must be better understood to inform any SRM decisions, he said, rather than simply avoiding any actions that carry risk.

"I think we've got to go a step beyond that and actually start quantifying the risks," Keith said.

In his email exchange with Newsweek, Hansen maintained that the global energy imbalance we have already created through air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions is a form of accidental geoengineering.

"We are already geoengineering the dickens out of the planet," he said. "I am suggesting that we reduce our geoengineering."

Rapid Warming

Aerosols are also at the heart of Hansen's argument about a rapid increase in global warming. Our industrial air pollution pumps massive amounts of particles into the atmosphere, contributing to millions of deaths around the world. But atmospheric science shows that those particles and the cloud droplets they help to form also reflect the sun's incoming energy, masking to some degree the full impact of warming due to the greenhouse effect of carbon dioxide.

Hansen called that a "Faustian bargain" that is now coming to an end as we clean up industry and transportation, as with the recently reduced particulate pollution from ocean-going cargo vessels.

Less pollution is good for our lungs but also means fewer particles blocking sunlight, and Hansen thinks that could significantly boost warming.

In his new paper, Hansen looks to evidence from the study of atmospheric and temperature changes in the Earth's deep history in order to better gauge how our current reduction of aerosols might affect warming. He concludes that the climate is very sensitive to warming when aerosols are reduced.

"The models used by IPCC tend to understate the role of human-made atmospheric aerosols," he said, and that implies that there is more warming on the way than the IPCC anticipates.

Hansen and his co-authors wrote in their new paper that "the scientific body advising the world on climate has not bluntly informed the world" that warming will likely exceed the IPCC targets.

The University of Pennsylvania's Mann and many other climate scientists disagree with Hansen on this point as well.

"It's fine for Jim to be skeptical and reject scientific findings," Mann said. "But it's important then to emphasize that he's taking a contrarian stance that is inconsistent with a wide body of mainstream thinking."

Mann said the recent global temperature increases are within the range of what climate models have predicted, and that there is no evidence that changes in ship-based aerosols, which Hansen emphasizes in the new paper, have played any meaningful role in recent warming trends.

And he added that there is strong evidence that natural systems that absorb CO2 will begin to draw down atmospheric concentrations if greenhouse gas emissions eventually stop, effectively slowing warming.

But Hansen said the assumption that emissions will stop is precisely the rub. His experience makes him skeptical that society will reduce emissions in time.

"The world cannot and will not instantly stop using fossil fuels," he said. "We have several years to help the public understand the situation while Earth continues to get hot enough for people to agree on the need for essential actions."

Climate Iconoclast

This isn't the first time Hansen has been at odds with others on climate science and environmental policy. Years ago, he was an outspoken critic of a climate policy proposal called cap and trade. That market-friendly approach would regulate the total amount of CO2 emissions and allow trading of carbon permits, and it was widely favored by many major environmental groups at the time. And unlike many environmentalists, he is a proponent of nuclear power.

"The fossil fuel industry, in cahoots with 'big green' environmental organizations blocked the development of modern, inexpensive nuclear power," he said in his email exchange with Newsweek.

In his new paper, Hansen reflects on his role as an iconoclast and the tendency among many scientists to reject new findings that challenge established ideas.

"The penalty for 'crying wolf' is immediate," he wrote, "while the danger of being blamed for 'fiddling while Rome was burning' is distant."

Hansen's warnings about warming now span parts of four decades, a record that raises an inevitable "what if" question: If society had responded sooner to climate scientists like him, would we even be in a debate over solar geoengineering?

"For sure we could have avoided the need for drastic measures," Hansen said.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.