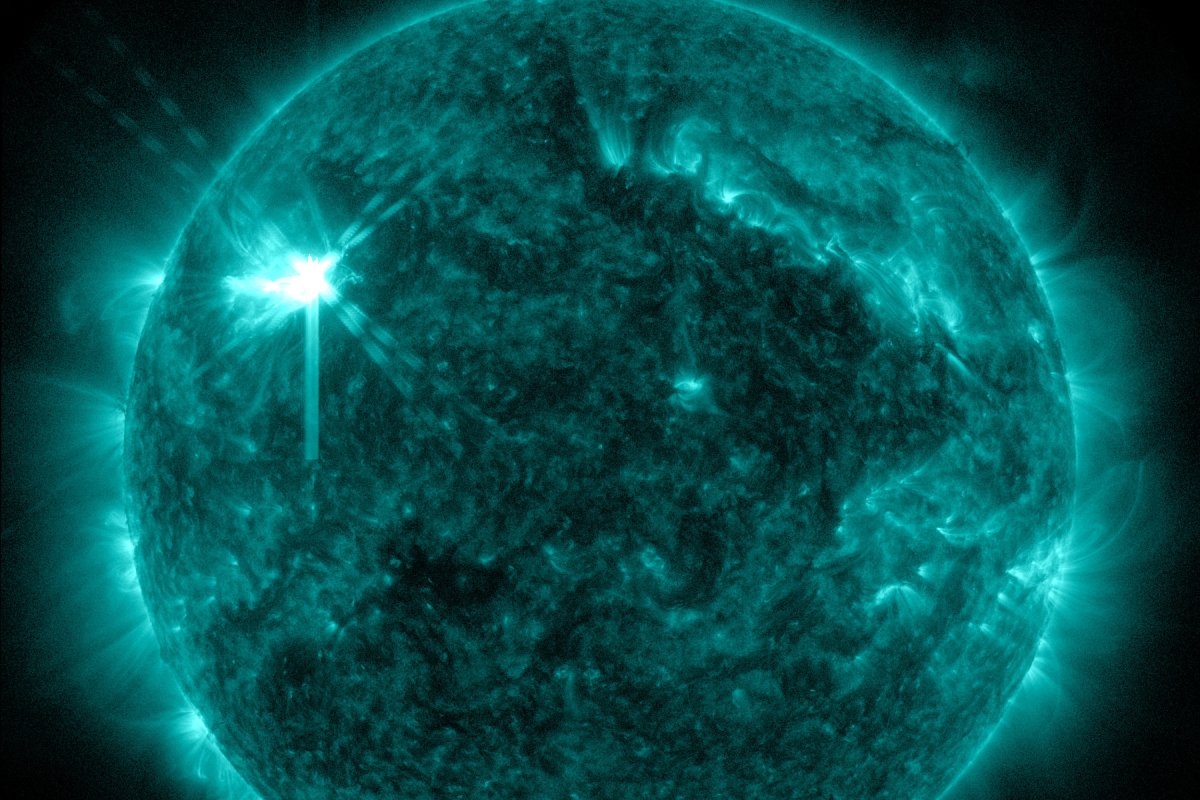

A powerful X-class solar flare hit Earth yesterday, causing radio blackouts over the U.S. West Coast and much of the Pacific Ocean.

The solar flare was spat out by a sunspot named AR3590, which has a volatile "beta-gamma-delta" magnetic field that makes it primed for X-class solar flares.

The flare that hit Earth on Wednesday was recorded as being X1.9-class, making it one of the more powerful solar flares.

"X1.9-flare now! Region 3590 fires a big flare at an R3-level #RadioBlackout over the Western Pacific, especially Western USA & Canada, New Zealand, Eastern Australia & Indonesia (colored regions in map). Although short-lived, expect more activity from this region!" space weather physicist Tamitha Skov posted to X, formerly known as Twitter, on Wednesday.

The same sunspot flung out an X1.7-class flare only a few hours later, Skov said in another post.

X1.9-flare now! Region 3590 fires a big flare at an R3-level #RadioBlackout over the Western Pacific, especially Western USA & Canada, New Zealand, Eastern Australia & Indonesia (colored regions in map). Although short-lived, expect more activity from this region! pic.twitter.com/9v2ufVTGou

— Dr. Tamitha Skov (@TamithaSkov) February 21, 2024

A solar flare is a sudden, intense burst of radiation emanating from our sun's surface, usually released from sunspots and other areas that have strong magnetic activity. When magnetic field lines on the sun's surface become twisted and stressed, it can lead to sudden releases of energy, often in the form of solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs). While CMEs are plumes of solar plasma, solar flares are eruptions of electromagnetic radiation, including X-rays and ultraviolet radiation.

Solar flares are ranked on a scale of A, B, C, M and X, with X-class flares being the most powerful. Each class is 10 times stronger than the last: an X1 flare is 10 times more powerful than an M1, and 100 times more powerful than a C1. X-class flares are more rare, however, and are only seen around 10 times each year.

"As an explosive event, [solar flares] can cause the X-ray level at Earth to go up dramatically, factors of at least a thousand or so as in this M-class event, or even more in X class flares. This can seriously affect the normally present level of ionization (breakdown of atoms) in the ionosphere at 50 to 60 (and more) miles above us and change what we are used to in how radio waves propagate, usually for the worse," Martin Connors, a professor of space science and physics at Canada's Athabasca University, told Newsweek.

Solar flares can cause radio blackouts on Earth, primarily in the 3 to 30 MHz band, due to the flare's high-energy photons ionize the gases in the upper atmosphere, particularly in the ionosphere. This ionization causes changes in the density and distribution of free electrons in the ionosphere. As the ionosphere plays a crucial role in reflecting and refracting radio waves, the flare's increased ionization can absorb radio waves across certain frequency ranges, especially those used for communication and navigation. This absorption prevents the radio waves from propagating through the ionosphere as effectively as they normally would, and causes blackouts.

X-class flares can also lead to radiation storms, which can impact satellite activity, and expose airlines to increased levels of solar radiation.

"The flare effect on radio is restricted to the sunlit portion of Earth, so cannot affect the whole world. Sometimes an X-ray flare is followed by more activity hours later (a proton storm, not likely this time) that affects northern and southern regions more than the area in sunlight. Since a lot of air traffic passes near the north polar regions, this type of storm can have a large impact on air traffic, and may also raise radiation levels at flight altitude slightly," Connors said.

X-class flares are more common as the sun approaches its solar maximum, which is the period of its 11-year solar cycle where it experiences the most sunspots and increased levels of flares and CMEs. The next solar maximum is due to occur between now and the start of 2026, so we are due to experience more frequent and more intense solar weather.

The most powerful X-flare on record was an X28-class flare which occurred in 2003. However, the Carrington Event in 1859 is thought to have been the most severe solar flare in history, causing significant disruptions to the telegraph systems around the world. Telegraph operators reported receiving electric shocks, telegraph systems malfunctioned, and some telegraph offices even caught fire due to the induced electrical currents.

If a similar event were to occur today, it could have far-reaching consequences due to our reliance on technology.

"If that were to happen today you can imagine just how much electronic equipment we depend upon and extrapolate how it is disruptive on earth," Alan Woodward, a professor of computer science and space weather expert at the University of Surrey, previously told Newsweek.

"Probably more immediate would be the impact on space-based systems as they don't have the protection of the atmosphere. Satellite safety is one of the reasons the solar weather watchers report as they do: it helps operators prepare their craft to withstand any flare,"

It is very unlikely that a Carrington Event-level flare would hit the Earth again in the near future, however.

"The chances of a flare affecting the Earth are lessened because the flares pop out in all directions decreasing the chance of them hitting Earth," Woodward explained. "The concern is if such a flare did ever affect the earth directly. It might be [a] 15 percent chance of one erupting but the chance it would come our way is much lower," Woodward said.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about solar flares? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.