How to Not Try

Trying too hard can be counterproductive and unattractive. Use your brain's cognitive control regions to shut down your brain's cognitive control regions.

Trying hasn't gone out of style. It was never in style. Cool is in style, and cool means moving through the world at once effortlessly and effectively.

Woven into most of our natures is a cumbersome desire to be accepted and liked. At odds with that is the equally natural tendency to be turned off by people who wear that desire on their sleeves. If you, like me, essentially reek of effort in all that you do, such that people can sense it blocks away, and it makes you unattractive socially and intellectually, and it makes babies cry, can you practice and learn to cultivate a genuinely spontaneous approach to life? Is it possible to be deliberately less deliberate?

Edward Slingerland offers some answers. He is a professor of Asian studies at the University of British Columbia. He trained in early Chinese thought at Stanford, but for the last decade he has immersed himself in cognitive neuroscience and social psychology. Right at that intersection sits his new book, Trying Not to Try: The art and science of spontaneity. In it, Slingerland offers prepossessing solutions to the problem of living, managing as best possible to make ancient philosophy concepts accessible to a wide audience without feeling like jejune misappropriation or commercialization.

He begins with two intertwined concepts: wu-wei and de. Wu-wei translates literally to "no trying" or "no doing." To completely distill a complex philosophical concept into one sentence: Wu-wei is like the automatic flow of being in the zone; often described as dynamic, effortless action, with elements of cultivated thoughtlessness and unselfconscious spontaneity. Some ancient Chinese philosophers considered it the source of all success in life. De (literal translation: "charismatic power") is a confidence without arrogance, a byproduct of wu-wei that, as a quality in others, people tend to find irresistibly attractive.

Slingerland describes reconciling the effortless action duality in a recent article at Nautilus:

Although talk of “mind” and “body” is technically inaccurate, it does capture an important functional difference between two systems: a slow, cold, conscious mind and a fast, hot, unconscious set of bodily instincts, hunches, and skills.

We tend to identify with the cold, slow system because it is the seat of our conscious awareness and our sense of self. Beneath this conscious self, though, is another self—much bigger and more powerful—that we have no direct access to. It is this deeper, more evolutionarily ancient part of us that knows how to spit and move our legs around. It’s also the part that we are struggling with when we try to resist that tiramisu or drag ourselves out of bed for an important meeting. The goal of wu-wei is to get these two selves working together smoothly and effectively. For a person in wu-wei, the mind is embodied and the body is mindful; the two systems—hot and cold, fast and slow—are completely integrated. The result is an intelligent spontaneity that is perfectly calibrated to the environment.

I spoke with Slingerland about how to be irresistibly attractive and successful without trying. I didn't go out of my way to talk with him, it just kind of appeared on my calendar and there we were, smiling and casually conversing with just the right amount of lightness and consequence. It went flawlessly.

How can I be effortlessly successful in this big, busy, dog-eat-dog modern world? [Editor's note: Begin by never saying dog eat dog again, even tongue in cheek.]

For the early Chinese thinkers, the goal was to get beyond striving. The ideal person for them is in a state where they’re not thinking, they’re not exerting effort, they’re not experiencing any doubts, and yet everything works out perfectly. Like just being on fire when you’re playing basketball, you’re not thinking; you’re absorbed in the activity and everything is going perfectly. The problem is, how do you get someone to be in that state if they’re not already?

A lot of the theories about human nature and self-cultivation that [these philosophers] develop are really all circling around the tension of how to try not to try. Part of what my book argues is that this is a real tension, and it’s something we should all be worrying about, too. We don’t tend to think too much about spontaneity because recent Western tradition has been more focused on rationality, self-control, discipline, cognitive control. We tend to, I think, feel that if you want to be different than what you are, the best way to go about it is to work really hard, and exert really hard, and try, try, try. And we miss the sides where that’s actually counterproductive.

There are a lot of areas in life where you really can’t succeed unless you’re not trying. So, like with people constantly focusing on happiness, there are obvious microcosms where you see this. If you have insomnia, and you’re trying to fall asleep, the more you try to fall asleep, the harder it is. If you’re in a social situation and you know you should be relaxed and confident, but you’re not feeling that way, thinking about it more and trying harder is actually going to be counterproductive.

I’m arguing that, for the ancient Chinese thinkers, this was their central worry, of how to get people who aren’t spontaneous to be that way. So they developed a lot of very sophisticated techniques for sneaking around the paradox in various ways. That’s the main thrust of the book, that in modern Western society, people who depend on being “in the zone” for their job—professional athletes, performers—think about this a bit. So they have terms for “being in the zone,” and various kinds of superstitions and strategies that they think help them stay in the zone. But I don’t think most people think about it.

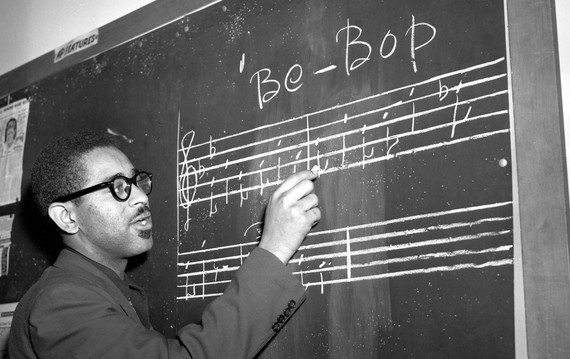

You write about jazz musicians and the various brain pathways that activate and disengage during improvisation. Kind of parallel to that, at Upright Citizens Brigade, the improv comedy theater, their motto is: “Don’t think.” For an improvising comedian, the apparent goal is to be incredibly clever and make connections, while also memorizing every detail that’s happening on stage so you can tie things together later in the show. Can you explain how the best approach to doing that effectively is not to think?

You could boil down the different strategies for "trying not to try" into four basic ones. It really is a tension, not just a trick of language or something, because you’re essentially trying to use your cognitive control regions to shut down your cognitive control regions. So that’s the trick. The first strategy is the Confucian strategy, which is “try really hard for a long time.” And to boil that down, it’s essentially if you train hard enough, eventually it become second nature and then you don’t need to worry about it anymore. Applying that to improv, maybe it would be, you do train a lot and have your little schticks that you’ve built up and you’ve watched other people do it, and you’ve tried it lots of times, and kind of not done so well, so you get to the point where you sort of internalize timing, or how to play off another person so that you can start doing it in a spontaneous way.

The second strategy, the Laozian strategy and Taoist strategy I view as a kind of corrective. Basically, the Taoists thought that Confucius had it all wrong; that if you trained in wu-wei, you would never really be in wu-wei. You’d just turn into kind of a hypocrite—someone who went through the motions. Apply that to improv or theater. If you’re overly manneristic or rely too much on tricks or stock things, you’re stiff or not able to change when things change, what you need to do is—the images that Laozi uses are things like returning to being like a child or being like the uncarved block. So, essentially he’s arguing that you basically need to stop doing anything and shut down your conscious mind completely.

Then you’ve got the third strategy, which is Mencius. So he’s a later Confucian and he’s trying to go the in-between route. He’s saying, look, we’ve got these spontaneous tendencies inside of us, we basically have the potential for wu-wei inside of us, but we need to cultivate it in a gentle way. His metaphor is agriculture. So, kind of like a farmer cultivating these sprouts and helping them get stronger. So I think that his strategy really applies to things where we do have tendencies that are helping us out and going in the right way, but we do need to do some work to strengthen them or expand them in some way.

The example I use for things like that is empathy. We do have a kind of innate empathy that doesn’t need working on. We see the puppy in the window and we feel bad. We have isolated instances of empathy, but we’re not very good at extending them in a consistent manner. So, we see the puppy and feel bad, but we walk right by the homeless guy and don’t notice him. So the Mencian strategy, I think, really applies more in cases where whatever it is we’re trying to get spontaneous at, we have the kind of seeds or sprouts of that within us, but we need to do a little work to extend them.

Then, the last strategy is the Zhuangzi strategy, which is another Taoist. He’s arguing a little bit like Laozi in that the problem is trying. So, essentially, the Chinese keep swinging back and forth between trying and not-trying strategies, but all of them are slightly different. With Zhuangzi, his dominant metaphor is emptiness, so, you make your mind empty, and if you can do that, then you’re open to the situation and you let the situation dictate your movements. And when you can do that—another big metaphor is “losing the self”—there’s no more you; you’re just being motivated by what is going on around you. The Zhuangzian approach is very appropriate for performers and athletes. It seems really in improv, that the key would be to just be tenuous. Be empty, to use a Zhuangzian metaphor, and just let the people you’re working with and the way the scene is going decide what your next move is going to be.

Yeah that's one of the tenets of improvising, that it’s all about reacting. That's one of the lessons people take into the real world. You can't be planning your next move while someone else is talking, because your next move is completely contingent on their every word.

It seems to me the Zhuangzian strategy is the one that’s the most appropriate for those situations: kind of high-speed, either performance or athletics where you really need to be receptive to whatever is going on around you. At the end of the book I lay out these strategies and talk about what’s the cognitive science and evolutionary theory behind each of them, and why they would work in certain situations, or be appropriate in certain situations. I argue the reason why none of these four strategies ever “wins,” is that there is no one best strategy. Which one is helpful probably depends both on the situation and what spontaneous situation you’re trying to get yourself to do, and probably also personality differences.

People tend to be born introverted or extroverted, or open to experience or not. And it’s also pretty clear that things like conservatism and liberalism are inborn, and certain basic tendencies. So it could be that certain strategies just appeal to certain personality types, and are more appropriate for certain personality types. This wu-wei ideal gets inherited in later East Asian religious thought; so Zen Buddhism picks it up and you basically see it throughout East Asia, and these four basic strategies just keep reappearing in different forms. I think the reason none of them wins out is because people need to do different things at different times.

Is there one way of thinking about this that seems to work best for people with social anxiety?

There, I think the kind of Laozian or Zhuangzian strategies. So the Laozian strategy, specifically, is aimed at tamping down goal-focused desire. I think the biggest problem for people, let’s say you’re not good at relaxing if you going on a date, it’s because you’re too focused on the goals. Like, I want this person to like me; I’m hoping that we’ll get to have a second date. Instead, what you really need to do is be like the uncarved block and just be simple and sincere, and that’s how it’s going to work out. So I talked a little bit in the Laozi chapter about books like The System or The Rules that give you these strategies for dating, and it just seems like none of those could ever possibly work, unless you actually just internalize them to a point where you really aren’t consciously following them any more.

Basically when you’re in wu-wei, the Chinese think you have this power that attracts people to you. So, if you’re a Confucian ruler, it’s what allows you to have people follow you without you forcing them; if you’re a Taoist, it’s what allows you to move through the world smoothly and allows people to get relaxed around you and not want to harm you.

What I argue in the book is that a naturalistic explanation of this power is that we trust people who are spontaneous. So people who are spontaneous are attractive because people have really good bullshit detectors. I go into some of the evolutionary game theory about why we’d be very worried about hypocrisy and people pretending to be something they’re not, and why we develop, through biocultural evolution, this tendency to like people who seem like they’re not trying. That’s very related to the social success aspect of wu-wei. You’re successful on a date when the person feels like they’re really meeting you and not something you’re putting on. Or a job interview, you tend to do better if you seem like you’re actually relaxed and really being who you are instead of putting something on that you think the interviewer wants to see.

Agreeing that there is a lot to be said for being genuine and living in the moment, is there ever a point where spontaneity becomes too much? When you’re the person who’s so totally in the moment that you don't get a flu shot, or don't pay bills, and you figure it'll all work itself out tomorrow?

That’s where I think the Confucian idea is important. Confucians think you really have to try and the end goal is wu-wei, but wu-wei properly understood doesn’t involve just sitting around and being natural if sitting around and being natural means you don’t get a flu shot or a job. This is where I think the person-specific nature of the strategies is important. I tend to be goal-directed and I like to plan things, so I’ve been drawn more to the Taoist, Laozi, Zhuangzian, be open thing. Whereas I think that people who may tend to be naturally relaxed and not goal-directed, maybe need a bit of the Confucian, let’s do some training and develop some new dispositions.