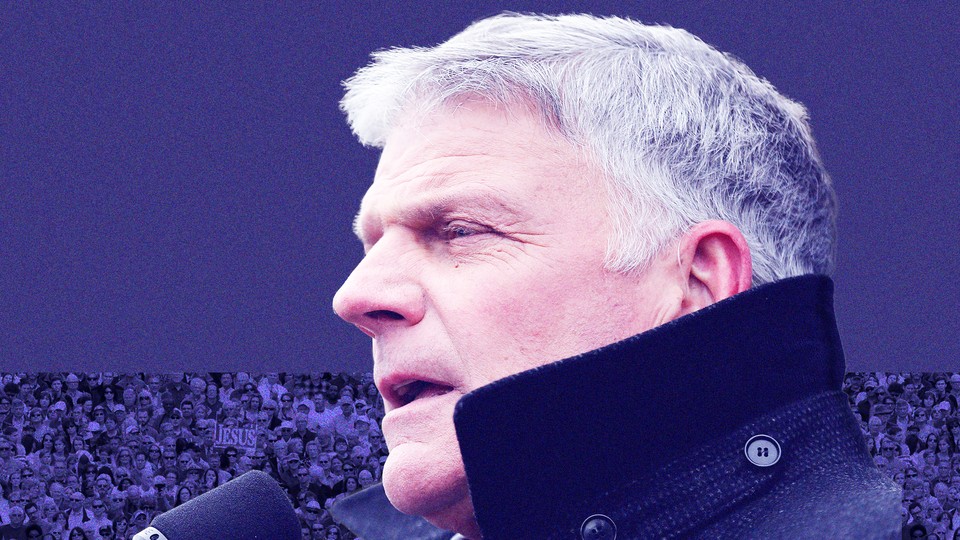

Franklin Graham Is the Evangelical Id

The famous preacher’s son embodies all the contradictions of Trump’s America.

Franklin Graham is a man of contradictions. He’s devoted his life to preventing persecution and helping those who face terrifying violence, yet he sees gay Boy Scouts as a major threat to children. His mission field knows no borders, but he’s proposed a total ban on Muslims entering the United States. He claims to hate politics, yet maintains a prolific, politicized Facebook page. And when he looks at Donald Trump, he sees God at work in the White House, not a president who would fire an FBI director while under investigation, brag about groping women, and give away state secrets over small talk.

Billy Graham’s son—a pastor in his own right who leads his father’s evangelistic association and the charity Samaritan’s Purse—represents in one person the best impulses of Christianity and the contradictions that have confused many Americans about what white evangelicalism stands for. He is the evangelical id. He speaks plainly, without any mind to political correctness, to an extent that has sometimes chagrined even fellow conservatives. When he looks ahead to the next four or eight years, he sees great hope, and when he looks to his fellow Christians, he sees only unity. Graham has a devoted following: He attracts big crowds at his rallies and has millions of fans on social media. But he’s also been a polarizing figure within evangelicalism, particularly among the young, and has alienated those who wish he would take a more welcoming tone toward non-Christians.

Franklin Graham may not be the presidential adviser his father was. But his version of Christianity is being lived out in America right now, with unknown consequences ahead.

Graham spent a recent Friday morning cooped up in a hotel room in Washington, graciously trudging through a marathon of media interviews. He seemed out of place in his mustard-yellow chair, dressed in a conservative dark suit and bright blue tie; the sprawling suite could have been the centerfold of a hip homes catalog, all chrome accents and inoffensive geometric shapes. “I try to avoid this city as much as possible,” he told me with a smile.

He had come to Washington to host the first-ever World Summit in Defense of Persecuted Christians, featuring a who’s who of evangelical heavy-hitters and D.C. elites from the Texas megachurch pastor Jack Graham to Vice President Mike Pence. More than 600 victims and advocates from 130 countries gathered to discuss and raise awareness about violence against Christians around the world.

It wasn’t a typical venue for Franklin. His controversial political views and famous father should make Graham the ultimate consigliere for Trump, who has surrounded himself with Clinton-era culture warriors. But aside from a recent White House cameo with his daughter, Cissie, Graham doesn’t enjoy the same kind of influence in Washington as people like Jerry Falwell Jr., another celebrity-evangelical son. During the 2016 election, Graham led a 50-state prayer campaign but refused to endorse a candidate. He speaks to Donald Trump “not that often,” he told me. He doesn’t want to “hang around looking for opportunities to go to the White House or to go to some senator’s office,” he said. “I don’t have time for that.”

Graham says he feels called to something different. Building on his work with Samaritan’s Purse, an evangelical aid organization that provides disaster relief and medical care, Graham has become an unofficial international ambassador for God and country. In doing so, he’s come to embody a certain kind of evangelical culture within the United States.

Graham recounts high-profile diplomatic encounters like they’re scenes from a Harrison Ford thriller. After a Samaritan’s Purse hospital was bombed, he met with the president of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir—“just a wicked man,” Graham said, who, indeed, has been accused of war crimes by the International Criminal Court. (He has also reportedly been invited to a summit with Trump in Saudi Arabia; if both attend, that would break with longstanding American norms.)

“So I met with him and I said, ‘Mr. President, I’ve come to ask you to quit bombing my hospital,’” Graham began.

“[Bashir] turned to one of his aides. He said, ‘Did we bomb this hospital?’

“‘Yes, Mr. President,’” the staffer apparently said.

“[Bashir] turned around and laughed,” Graham said. “He laughed, like it was a joke, like oh, ha ha, you got bombed.”

Graham went on. “The churches that he burned, I told him, I said, ‘Mr. President, I’m going back to the churches you destroyed.’ I said, ‘For every pastor you kill, I’m going to train two to take his place.’

“He didn’t laugh. He just looked at me. Then he said, ‘I want to make you a Muslim.’” Graham was incredulous. “He wants to make me a Muslim. Like he’s going to twist my arm or put a knife to my throat. And I said, ‘You know, Mr. President, I’m surprised that you would find me worthy to be a Muslim.’ I said, ‘I want to persuade you—not make, but persuade—to become a follower of Jesus Christ. I’d like to persuade you.’” This, Graham claimed, is “the difference between a Muslim [and a Christian]: The Muslims want to force conversion. Christians want to persuade you to voluntarily change your heart to where you would say yes to Jesus Christ.”

It’s not clear whether Graham expects his version of this colorful encounter to be taken at face value. But the themes of this bravado-full scene with a foreign president—good guys standing up to bad guys, a global struggle against evil, an inherent opposition between Islam and Christianity—are constant in Graham’s thinking. Several times during our conversation, he repeated Trump-administration arguments about refugees: Some of the Muslims who try to come to the United States “are not legitimate,” he claimed. “We live in a dangerous [world], where we need to be more careful, and do a better job of vetting anyone who comes into America.”

There’s reason to fear what’s happening in America, too: “We’re in a sick world,” he said, “very sick.” Christians “have been targeted by the gay-lesbian groups, purposefully, to put them out of business,” he said, and “we are exposed to the gay lifestyle [through] television, music, school.” He believes that organizations like the Boy Scouts “have lost it,” he told me, because they have opened up their membership to LGBT kids and allow gay men to lead troops. “It’s not an organization that’s fit to exist.” He especially worries about the influence of gay troop leaders. “Gay couples cannot have children,” he said. “All they can do is recruit your child. … There’s going to be a lawsuit one day, where a child will be molested, and will have been taken advantage of … I hope the directors are going to be held accountable.”

There was more. He bemoaned political intolerance: “The hatred, especially on the left, is incredible,” he said. “Their hearts are filled with hate.” And he described his objections to the way he believes Islam is practiced in the United States, mentioning honor killings—violence against women who shame their families—and “the mutilation of a young woman’s sexual areas so that sex is painful for them, and therefore they supposedly will be faithful to their husbands because of pain,” as he described it. “That happens a lot.” (So-called honor killings are difficult to define and track. The prevalence of female genital mutilation is also challenging to document, although evidence suggests it may be limited to specific ethnic or nationality-based communities. Authorities recently brought charges in the first case of female genital mutilation in the U.S. to be prosecuted under a federal statute specifically barring the practice.)

As I sat waiting for our interview, Graham told a reporter from the evangelical magazine World that the persecution Christians face in the U.S. is “maybe not having your head cut off,” which is what happens to religious minorities in the Middle East. But “there’s not too big of a difference here.”

Graham takes comfort in Trump’s election. “He did everything wrong, politically,” Graham told me. “He offended gays. He offended women. He offended the military. He offended black people. He offended the Hispanic people. He offended everybody! And he became president of the United States. Only God could do that.” Now, there’s “no question” that God is supporting Trump, Graham said. “No president in my lifetime—I’m 64 years old—can I remember … speaking about God as much as Donald Trump does.”

It’s Trump’s signaling that seems to matter most to Graham. The president stood in the Rose Garden and declared that “we are giving churches their voices back”; he sent Pence to speak at Graham’s summit on persecuted Christians. In this, Graham finds optimism: “I saw the evangelicals come out by the millions in this election. Many hadn’t voted for years,” he said. “[I] never told them how to vote. But I said, ‘Pray before you vote.’”

As for those Christians who worry about Trump, those of color, those who wish their leaders would be more welcoming toward Muslims and LGBT people even if they disagree with the way they live: “I don’t think there’s a divide,” Graham said. If they have problems with Trump, and with role white evangelicals are playing in this era of politics, “talk to God about it,” Graham advised. “If they’re hurt, sorry. … I believe Donald Trump’s there because God put him there.”