At the Ripe Age of 105, IBM Seeks to Reinvent Itself—Again

Going into its 106th year, IBM faces existential challenges.

Say what you will about IBM—and at this point, nearly everything has been said—it is the only tech giant to reach the ripe old age of 105. The company has weathered many a storm since it launched as the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company in 1911.

IBM has made tabulators, giant disk drives, mainframes, midrange computers, PCs, and associated software. It invented or helped invent the bar code, the magnetic stripe found on credit cards, and the scanning tunneling microscope used in materials science and physics research. In the 1990s, IBM started building a giant IT services business that became the envy of competitors, including Oracle, Hewlett-Packard and Dell.

There have been stumbles along the way. In one example, IBM’s army of lawyers let it sign a contract allowing Microsoft (MSFT) to sell a version of the PC-DOS operating system it developed for IBM to any PC maker. That paved the way for a raft of PC clones that helped Microsoft—not IBM—to dominate the PC era.

Paul Allen, from Asymetrix Corporation/Vulcan Inc., and Bill Gates, from Microsoft, share a laugh at the annual PC Forum in Phoenix, Arizona in February of 1987.Ann E. Yow-Dyson — Getty Images

IBM (IBM) has always soldiered on. It touted breakthroughs in chip design and artificial intelligence by its vaunted research team while laying claim to a library of patents.

But in the past few decades, the company has also drawn attention for laying off tens of thousands of employees and divesting itself of lower-margin businesses, including selling its PC business to Lenovo in 2004.

From the Fortune archives: How IBM Teaches Techies to Sell

That’s the narrative that Ginni Rometty, now into her fourth year as chairman and chief executive officer of IBM, has to change. The question is whether she can or will do it fast enough. At this stage of the game, even dramatic moves like selling off IBM’s server business (again to Lenovo) and divesting its chip fabrication business won’t be enough to assure its legacy. She has continued to invest in artificial intelligence, or cognitive computing, as exemplified by the always-touted Watson artificial intelligence services as well as IBM’s cloud computing unit.

Under Rometty’s watch, IBM bought the Weather Company for its data trove and whizzy technology for the emerging Internet of things for an estimated $2 billion. It followed up by buying Truven Health for a reported $2.6 billion to give Watson more data and healthcare expertise to ingest.

Rometty herself summed up IBM’s quandary at the recent Code conference in May. “It’s easy to have an act one and two. Go ahead and have an act three, four, and five. The saying is the easy part, the doing is the hard part,” she remarked. “You have to change business models, products, and everything about yourself and what you stand for.”

IBM did not respond to Fortune‘s request for comment on this story.

IBM proponents say she has placed the right bets. Those wagers have included selling off older, less profitable businesses to focus on key bigger opportunities like artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and security. Although it does not break out specific sales and usage numbers for Watson, IBM asserts its artificial intelligence or cognitive services can solve big problems and will be a huge business some day.

Watson does represent a triumph of messaging—if not profitability. A public relations executive for a big IBM competitor somewhat shamefacedly admitted (but not for attribution) that IBM’s marketing for Watson has been a ringing success. Just look at its presence on the red carpet at the Metropolitan Museum’s Met Gala in May, she highlighted.

“Apple (AAPL) was the sponsor, but the only tech company that got any mention was IBM for Watson,” she said. Why? Because Watson helped design a spectacular LED-encrusted “cognitive” dress that stole the show.

Rometty, left, and Kenichi Yoshida, vice president of business development for SoftBank Robotics, stand near SoftBank’s robot Pepper as it waves to the audience during an IBM keynote address at the 2016 CES trade show in Las Vegas, Nevada January 6, 2016.Steve Marcus — Reuters

Some analysts suggest that IBM’s braintrust has the intestinal fortitude to keep on going.

“What many people don’t understand about IBM is that in its core, it’s a ferocious fighter. It’ll do what needs to be done,” said Judith Hurwitz, founder of Hurwitz & Associates, who often consults with IBM. “What makes IBM’s path harder to understand than what HP and Dell are doing is that it’s almost doing a heart transplant on itself and doing it in public.”

She credits the company for buying SoftLayer a few years ago in order to replace what had been a confusing and disjointed set of its own cloud products.

Roger Kay, founder of Endpoint Technologies Associates, another long-time IBM watcher and sometimes-advisor, agreed. In his view, IBM is putting its money where it counts, hinting IBM doesn’t feel it can add value competing node-for-node with Amazon Web Services in data centers. Instead, there could be more value in offering access to IBM’s cloud and related services, including the ability to pose business questions to Watson, for example.

“It’s philosophy is to invest in areas where it believes it can have a competitive advantage,” Kay explained. “In the Watson self-teaching technology, for example. They got rid of chip fabs because they didn’t feel that as a foundry they could contribute to the conversation. The volumes weren’t big enough.”

From the Fortune archives: How Steve Jobs Linked Up With IBM

Kay is particularly excited by IBM’s work in the cutting edge realm of quantum computing. Last month, IBM made an early version of a quantum computer available to researchers who want to test it out. The technology is complex to explain (more here), but a specialized quantum processor can crunch huge amounts of data fast and could lead to breakthroughs in decryption and security applications.

Critics have another take, which is that the best Rometty can do at this point is to manage a graceful decline. They slam her predecessor, Sam Palmisano, for saddling the company with his 2012 pledge to hit $20 earnings per share by 2015. “Not very nice of him,” quipped Forrester Research (FORR) founder and chief executive George Colony.

Rometty finally jettisoned that goal—some would say too late—in the fall of 2014. Nonetheless, as Kay pointed out, despite having reported 16 consecutive quarters of revenue declines, IBM still pays out a dividend of $3.50. This comes at a time when old line competitors pay a fraction of that, if anything.

A common refrain among the fatalists is that IBM may be doing its best but it’s too little, too late. They think the company spent so much time, money, and energy on financial engineering and were too late to the cloud computing wave that Amazon (AMZN) Web Services is riding. In this model, large providers like Amazon, field huge arrays of servers, storage, and networking, to run customers’ computing workloads. That’s attractive to businesses that don’t want to expand or build out more of their own data centers that run the types of gear IBM sells.

Somewhere between the bulls and the bears are skeptics who think that it’s not too late for IBM to resurge, provided it does something truly radical—much more radical than dropping a few billion here and there. IBM has to get bold. Really, really bold, specified the chief executive of a security company with close ties with IBM, who requested anonymity because of those relationships.

“You can’t cut your way to growth. There are some massive opportunities in the market. IBM needs to take some big risks, maybe buy Box (BOX) or Dropbox. IBM and Symantec are pretty similar. Growth is stagnant, they’re in survival mode, maintaining their earnings per share,” noted this executive. Lo and behold, Symantec (SYMC) went out and bought BlueCoat for $4.65 billion this week.

He’s hoping IBM might get inspired by that or by Microsoft’s even bigger $26.2 billion buy of LinkedIn, which may spark a resurgence in big-time tech M&A.

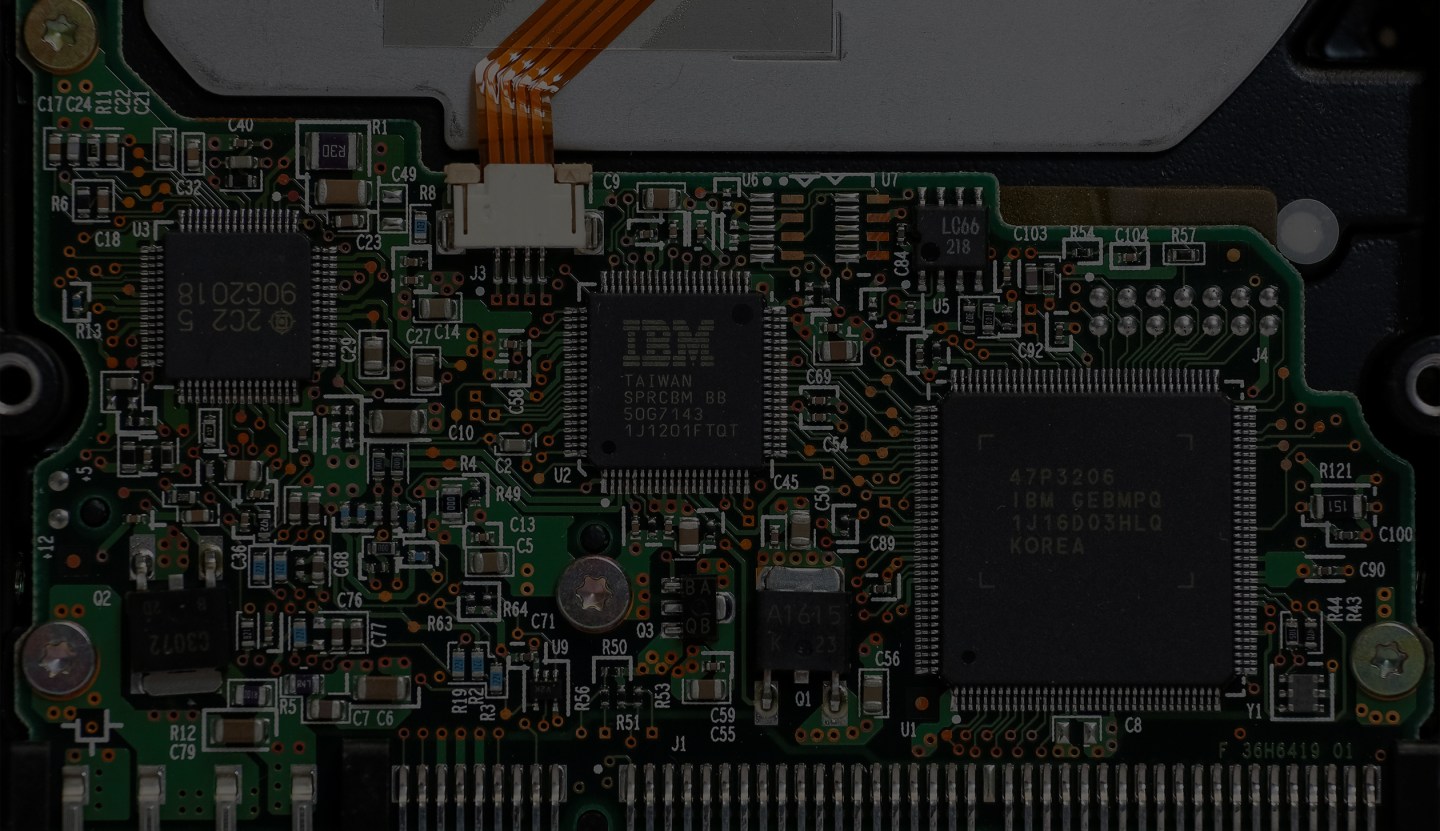

IBM INVENTIONS (Clockwise): The Hollerith tabulator and sorter box, invented by Herman Hollerith and used in the 1890 United States census, the IBM System/360, then-President & CEO of IBM John R. Opel (seated, center) demonstrates his companies personal home computer in New York on August 13, 1981, and Watson.Photos by (clockwise) Hulton Archive/Getty Images; IBM; Ralph Morse — The LIFE Images Collection; IBM

Ceding the consumer market turned out to be a mistake

Forrester’s Colony agrees. IBM’s ties to corporate buyers are a big asset, as is the fact that IBM gear runs the banks, the airlines, the trains of the modern world. But IBM, under Palmisano, ceded the consumer market with the sale of the PC business, and that has come back to bite it, he said.

“If you look at the big tech players from the old enterprise world, IBM, Cisco (CSCO), Microsoft, and Oracle (ORCL), they had a combined market cap of $850 billion or so at end of 2015. Now look at the consumer powers—Facebook, Apple, Google, and Amazon. Together their market cap is $1.8 trillion. More than double. So you can see where the market is shifting and capital is going,” Colony said.

Get Data Sheet, Fortune’s technology newsletter.

Chief information officers today now have to manage two big pools of technology. They still manage the internal IT—the databases, email, desktop apps, and associated hardware—they’ve always handled. But in the last few years they, sometimes along with their chief marketing officers, also have to deal with what Forrester calls “business technology.” That’s all the cloud services and software tools needed to create and run web sites and mobile apps—the tools that companies now use to connect with, woo, win, retain, and serve their customers.

That means IBM’s traditional CIO client base now has two agendas, one of which IBM is not addressing and needs to start dealing with pronto, in Colony’s view. “That great IBM franchise in IT is very important, but it’s not where the future is,” he noted. To reverse course, he and others think IBM has to get itself in front of consumers in a big way—probably via big acquisitions.

From the Fortune archives: Dangerous Liaisons at IBM: Inside the Biggest Hedge Fund Insider-Trading Ring

Several IBM watchers mentioned that the company should look into buying Dropbox, Slack, or even Salesforce (CRM). It has, after all, already purchased one of Salesforce’s largest services partners in Bluewolf Group. Colony even threw Snapchat on the list before noting that might be a bit of a reach.

“Dropbox would be a good move, but they’d have to hold their nose, overpay, and then take a lot of heat from investors,” he noted.

The consensus opinion here is that IBM has made some good strategic buys in things like the Weather Company and Truven Health. But IBM needs to get much, much bolder to make itself a front runner in this brave new world that blends back-office IT power and the consumer world.