Twenty-three activists, business and labor leaders, civil servants, doctors, and academics were sworn in Thursday to serve on President Joe Biden’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.

Among them was Minnesotan KaYing Yang, who arrived in the United States at the age of 7 as a Hmong refugee. Yang, 53, has dedicated the past three decades of her life to working for social justice as part of a number of local, national, and international organizations and movements.

She is the third Minnesotan to serve on the commission, which she helped launch in the 1990s. “It tells you that the state of Minnesota is a very important state for Asian American representation,” said Yang. “As a Minnesotan, I’m really pleased and proud to be an appointee for this administration.”

It’s been a long journey for Yang to reach this milestone — a journey familiar to many in her community in Minnesota, with its roots in the American war in Vietnam.

In the mid-1960s, Yang’s father, then a teenager, was recruited by the CIA to join the American fight in Southeast Asia. He served the agency for nearly a decade before arriving in Columbus, Ohio, without any knowledge of the English language.

The family’s first few years in the U.S. were difficult.

“I did not see a lot of joy, because I think that adjustment was very challenging,” Yang said.

related stories

Yang’s family soon moved to Wisconsin and found a strong and supportive Hmong community, but Yang still experienced racism routinely. Those experiences, along with her parents’ struggle to support their family economically, helped shape her world view.

After arriving in the U.S., Yang’s mother found work as a room cleaner at a Ramada Inn hotel, while her father worked as a custodian. They later became factory workers. Yang’s family shopped at second-hand stores and church sales

When Yang was a teenager, she wanted a pair of Levi’s jeans. Her parents, not for a lack of effort in their work lives, couldn’t afford it.

It was only years later, after Yang moved to Washington, D.C., that she bought her first new mattress at a Sears, which took her years to pay off.

Economic poverty, she said, is the result of leaders’ policy choices.

“Right now, I feel like all of our poverty alleviation programs really are very punitive on the poor,” Yang said. “Knowing how hard my mom and dad worked, and still struggling, tells me that there’s something wrong with the system. It’s not them. They worked hard.”

“Right now, I feel like all of our poverty alleviation programs really are very punitive on the poor. Knowing how hard my mom and dad worked, and still struggling, tells me that there’s something wrong with the system. It’s not them. They worked hard.”

KaYing Yang

Several years after graduating from the University of Colorado in 1991, Yang moved to Minnesota to serve as executive director of the Women’s Association of Hmong and Lao before heading to Washington, D.C., to lead the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center.

Refugee camp work

In the late 1990s, when Yang was establishing herself as a community and policy leader, ThaoMee Xiong, then a political science and government student at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, interviewed Yang for her senior thesis.

In 2004, as a second-year law student, Xiong took a semester off and moved to Thailand in hope of working in a Hmong refugee camp. Yang, who was in Thailand working for the International Organization for Migration, got her a job.

In Thailand, Xiong saw the full force of Yang’s abilities, both as a policy expert and as a person. Xiong said Yang spent her days working directly with refugees in the camp and then, in the evenings, got on the phone with colleagues in Washington to strategize on resettlement issues.

“I was always planning the next step, but she already planned 10 steps ahead of my next step,” Xiong said. “That’s the level of expertise and experience she brought with her. I was constantly in awe of her ability to quickly maneuver through really complicated situations.”

“I was always planning the next step, but she already planned 10 steps ahead of my next step. I was constantly in awe of her ability to quickly maneuver through really complicated situations.”

ThaoMee Xiong on KaYing Yang

In 2015, after working for several more years in Thailand and her native Laos, Yang returned to Minnesota as director of programs and partnerships for the Coalition of Asian American Leaders.

Now she finds herself on a national stage. Yang said she takes her responsibility as a representative of her adopted state very seriously.

Minnesota’s Asian American community differs from U.S. coastal Asian American communities in significant ways. It is largely composed of newer immigrants and refugees from Southeast Asia, many of whom are dealing with distinct challenges.

“We bring a very different perspective, because the Southeast Asian population, within the Asian American diaspora, is very young and new,” said Xiong, who now works with Yang at the Coalition of Asian American Leaders in Minnesota. “The socioeconomic, cultural dynamics are very different from anywhere else in the country.”

Yang and Xiong have sought to elevate issues facing Minnesota’s Southeast Asian community, pushing legislators to implement data analysis practices to help policymakers and advocates better understand the specific challenges their communities face.

Yang said her goals on Biden’s advisory commission will be to raise awareness of the diversity of the Asian American community and represent the specific interests of Minnesota’s community and that of the Midwest at large.

“How can we lift up and understand the diversity of Asian Americans and not always think that Asian Americans are the model minority?” Yang said. “When we say that Asian Americans are overly represented or are all doing well, we are basically doing a disservice to the communities that continue to struggle.”

“How can we lift up and understand the diversity of Asian Americans and not always think that Asian Americans are the model minority? When we say that Asian Americans are overly represented or are all doing well, we are basically doing a disservice to the communities that continue to struggle.”

KaYing Yang

The presidential recognition was an unexpected honor, Yang said. Last spring, she had filled out a form indicating her interest in working with the Biden administration commission, but she estimated that her application was one of thousands.

In a sense, Yang’s inclusion on the advisory commission has been a long time in the making. In the 1990s, she was part of a group that worked with the Clinton administration to help launch the commission.

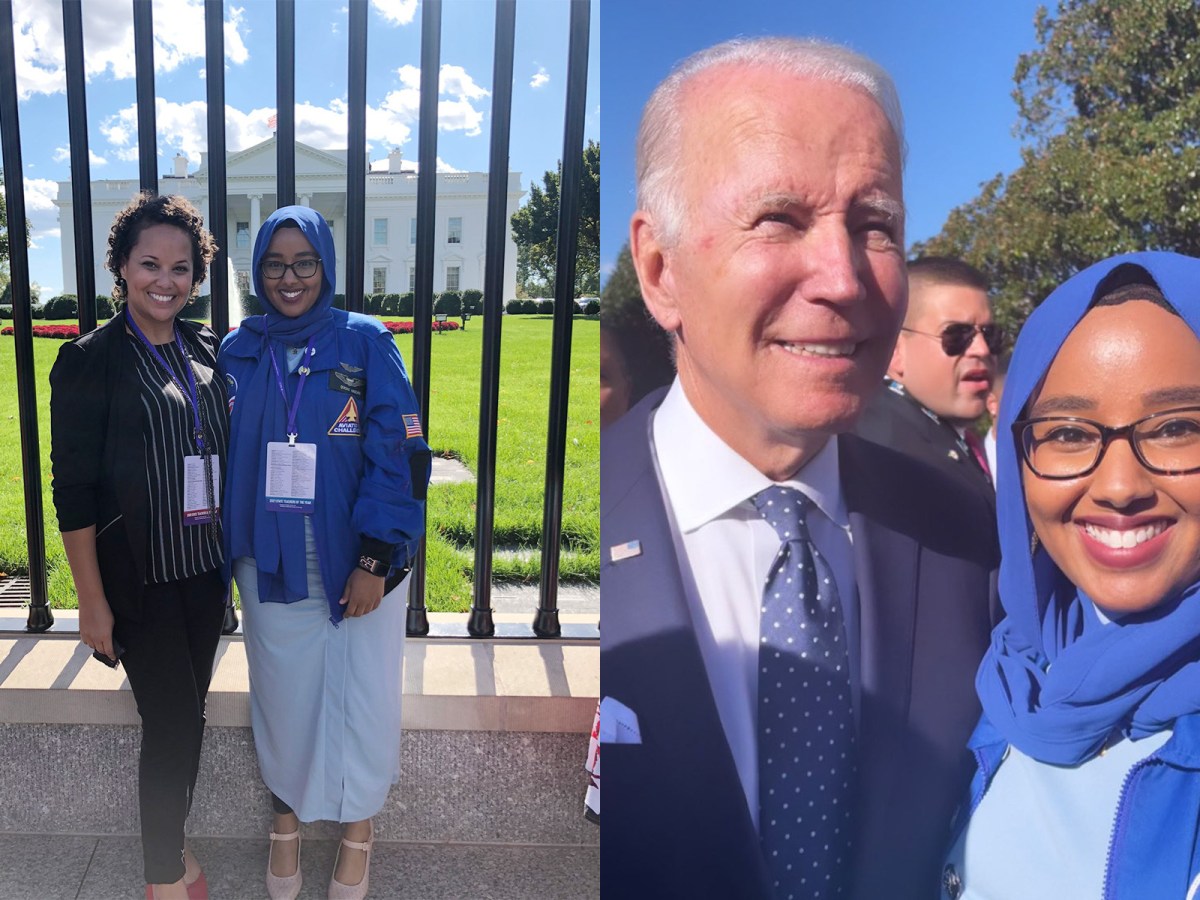

Yang will be working with a president whom she campaigned for. In the fall of 2020, she volunteered with Hmong Americans for Biden, and in the month before the election, she met with Jill Biden when the now-first lady campaigned at the Hmong Village Shopping Center in St. Paul.

Yang said then that she was excited both by her community’s ability to play a decisive role in the election outcome and by vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris’ inclusion on the ticket—but that she wanted results from the Biden administration.

“We want immigration reform that unites families instead of breaking up families,” Yang told Sahan Journal after Jill Biden’s campaign stop. “And we want affordable health care, just like everyone else.”

Primed to push for change

Immigration and health care are areas in which many feel that the Biden administration has made little progress. Xiong said that she will push Yang to work hard for immigration reform during her time advising the administration.

“We need action on immigration,” Xiong said. “This is tearing families apart. It’s breaking the fabric of our communities and it’s also creating a cycle of poverty, because many of the individuals who are being deported are heads of households.”

Yang, who has been working to try to stop deportations, said she won’t be shy about raising the issue.

“The issue of immigration is very important, and this is precisely why it’s important to be participating in such a commission—so we can raise the issues up to the highest level of government,” she said.

Other areas of focus for Yang include addressing the spike in anti-Asian hate crimes, highlighting the achievements of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and breaking down language barriers that often keep non-English speakers from receiving government assistance.

“I still look to her as a pioneer,” Xiong said. “The things I respected and admired about her when I was in college still ring true. She really is a great problem-solver. At the core, she brings everything back to the community, which is very hard to do, and many people don’t do it well.”

Yang said she regrets that her parents weren’t able to join her for the in-person induction ceremony in Washington. But she knows that they are proud of all that she has accomplished and the fights she continues to be engaged in.

“They just know that I’m a troublemaker in some ways,” Yang said. “But I think now they know it’s for the benefit of the community — and they try not to hush me so much.”