How You Turn Music Into Money in 2012 (Spoiler: Mostly iTunes)

Less than $300 from Spotify. More than $45,000 from iTunes.

Talking about how he makes money, the independent musician Jonathan Coulton has compared his business to a "special engineered cow who eats music and poops money." Coulton doesn't have any idea what happens inside the cow's gut, but that's okay. Money comes out the business end.

And that's how it is for most online musicians, or artists generally, in today's digital economy. If they're lucky enough to make money, they may not heavily analyze the particulars. They feed the cow music, and out comes the money.

So it's rare that we, as consumers or fans or fellow artists, get the ability to see exactly how successful makers support themselves: to look at the source of their earnings, and to glance up into the cow's -- well, I'll cut this metaphor now.

The avant garde cellist Zoe Keating has allowed us see her revenue model. Earlier this summer, she posted the details of her Spotify earnings, revealing that every time someone listened to one of her songs, she made about three tenths of a cent. She also posted her iTunes earnings at the time.

But yesterday, she augmented that data with new material: what she makes from Pandora, radio plays, and her participation in the royalty-collecting American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (which everyone calls ASCAP).

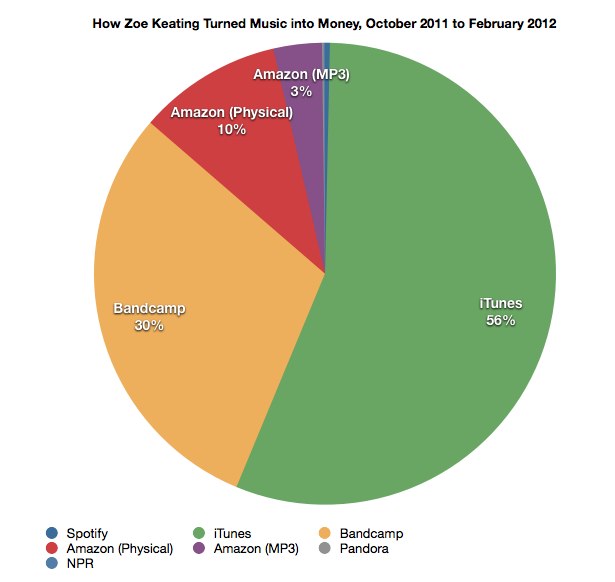

During those six months, Zoe Keating made (before taxes) $84,385.86. This is where that money came from:

Just taking a first look at these data, it becomes clear that buying music from artists directly -- through iTunes, Amazon or Bandcamp -- is the best thing you can do to support their music-making. Keating made 97% of her revenue through people just buying her music, whether through physical sales or digital download. Spotify subscribers pay their ten bucks a month for the service, and that even feels like a healthy little monthly gift to music-making. But it's not nearly as helpful to the artists as buying an album or a song from iTunes, Bandcamp or Amazon.

And this is a point Keating makes herself: that digital distribution -- even through iTunes -- most helps artists because it removes the middle man. In notes attached to her Google Doc, she writes:

The income of a non-mainstream artist like me is a patchwork quilt and streaming is currently one tiny square in that quilt. Streaming is not yet a replacement for digital sales, and to conflate the two is a mistake. I do not see streaming as a threat to my income, just like I've never regarded file-sharing as a threat but as a convenient way to hear music. If people really like my music, I still believe they'll support it somewhere, somehow. Casual listeners won't, but they never did anyway. I don't buy ALL the music I listen to either, I never did, so why should I expect every single listener to make a purchase? I think that a subset of my listeners pay for my music, and that is a-ok because...and this is the key.....there are few middlemen between us.

And there's one more point here, about streaming services and their similarity to radio (which, for Keating, means income from NPR in both its satellite and terrestrial broadcasts).

When Keating first revealed her streaming revenue, many compared her earnings from Spotify to radio royalties. That is, they're not worth much by themselves, but in the aggregate, they bring in some cash. The two have little in common as services -- when listening to the radio, you're not your own DJ -- but today's numbers both do and don't support that economic thesis.

During the fourth quarter of 2011, Keating made $77 from NPR and $149 from Spotify. But zoom out a bit, and it seems that a great month in radio reaps profits that streaming services can't touch. Last year, from April to December, Keating made $271 from Pandora -- and $640 from NPR. Radio helped Keating far more than streaming did. And advertising data might support that: according to this Mary Meeker slideshow, while Americans spend 11% of their time listening to radio, advertising companies (who drive the worth of the medium) spend 15% of their budgets there.

Ultimately, though, data from Keating alone don't provide enough evidence to know how the music business works right now. "I admit I have grander designs" than revealing the innards of her music-making cow, writes Keating in the Google Doc:

[I]f we are going to discuss the ideal structure of the new music industry, we need to know how recording artists make a living today or we're just spouting hyperbole. So, in the interest of evolving the discussion, I am making myself into a data point. I encourage other artists, if they are able, to do the same.

Let's hope so.