Lead Poisoning in Rome - The Skeletal Evidence

A friend alerted me to an IO9 post, "The First Artificial Sweetener Poisoned Lots of Romans." It's a (very) brief look at some of the uses of lead (Pb) in the Roman world, including the hoary hypothesis that rampant lead poisoning led to the downfall of Rome - you know, along with gonorrhea, Christianity, slavery, and the kitchen sink.

The fact the Romans loved their lead isn't in question. We have plenty of textual and archaeological sources that inform us of the use of lead - as cosmetics, ballistics, sarcophagi, pipes, jewelry, curse tablets, utensils and cooking pots, and, of course sapa and defrutum (wine boiled down in lead pots) - but what almost all stories about the use of lead in ancient Rome miss is the osteological evidence.

But let's start with some contemporary medical knowledge. Metabolic disorders can be caused by a lack of nutrients - a lack of vitamin C gives you scurvy, and a lack of vitamin D gives you rickets - but they can also be caused by an abundance of something, like too much fluoride, too much mercury, too much arsenic, or too much lead.

Lead is a heavy metal, one that isn't needed by the human body, unlike vitamins C or D. This element is found in the environment naturally, so we do expect to find some amount of lead in the skeleton of every person, ancient or modern. But, because of the physical properties of lead - it can be made into hard, sharp things - people have been using it for millennia and thus have been exposed to heavy metal toxicity for millennia as well. The dangers of lead actually weren't well known until the second half of the 20th century, which was when lead was taken out of things like paint and gasoline.

The main problem with lead - the reason that it's toxic - is that it interferes with normal enzyme reactions within the human body. Lead can actually mimic other metals that are essential to biological functioning. But since lead doesn't work the same way as those metals, the enzymatic reactions that depend on things like calcium, iron, and zinc are disrupted. The most damaging enzymatic reaction that lead affects is the production of hemoglobin, or red blood cell production, which can cause anemia. So doctors in modern times often find anemia in a person with lead poisoning. Lead is also particularly problematic because it stays in the body for a very long time once it's absorbed, inhaled, or ingested. Most of it gets deposited in the bones and teeth. Lead can be removed from the body, excreted through the kidneys and urine, but it's a very slow process without modern chelation therapy.

In modern society, lead poisoning is diagnosed through a blood test to determine the level of lead in the body. We don't have blood in ancient remains, of course, so we have to investigate lead through the levels we can measure in bone and enamel. As far as I know, the first and only study to actually measure levels of lead in skeletons from Rome is the one that involved my samples from the two cemeteries of Casal Bertone and Castellaccio Europarco (1st-3rd c AD).* The analysis was led by Janet Montgomery, now at Durham University, and also involved around 200 samples from Britain from the Neolithic to the Late Medieval periods (see below, Montgomery et al. 2010).

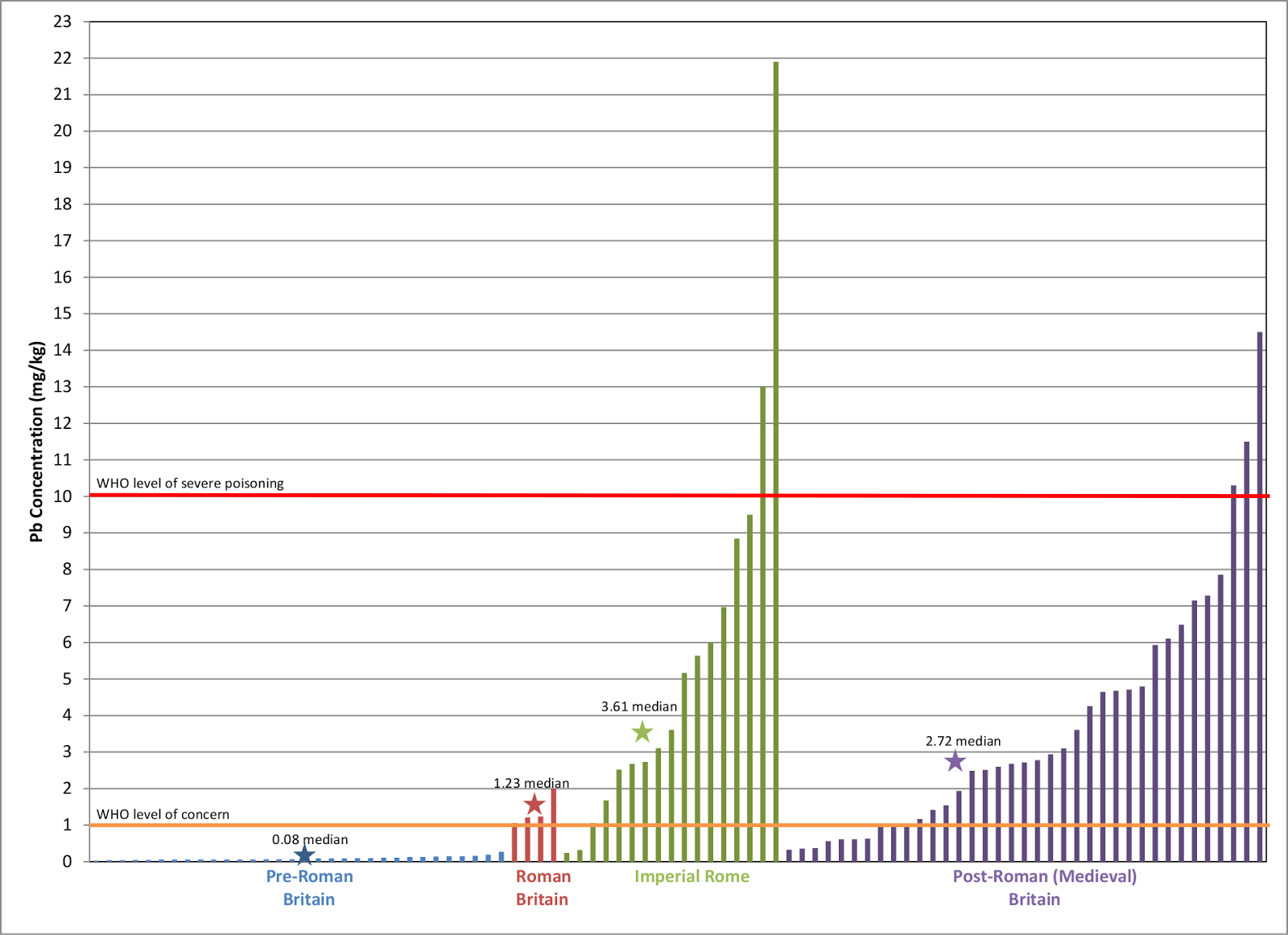

Some of the data from that article is below. The Romans are there in the middle. What you can see is that there are fairly low levels of lead in the pre-Roman periods in Britain (Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age) and the levels are lower in the post-fall of the Roman Empire (after 5th c AD). So what do those numbers mean on a scale of Normal to Lead Poisoned? Well, the modern recommendation by the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control is that children should not have more than 1 mg/kg of lead in their bones (or 10 ug/dL measured in blood). Back to the chart, where I've inserted a bright orange line at 1 mg/kg, and no one in the pre-Roman period is getting poisoned. The Imperial period is pretty special - we've got a person with lead levels over 20 mg/kg, which is 20 times higher than modern recommendations! In fact, this level is two times higher than the level the WHO considers "very severe lead poisoning."

It's not yet clear what the data mean, though, other than that some people likely had lead poisoning and others didn't. The sample size is fairly small, and more importantly, I don't know where in Rome people were living. That is, if the people buried at Casal Bertone and Castellaccio Europarco were living in an industrial area or were metalworkers, then they were more at risk for high levels of lead than were people not living in those areas and not doing those jobs. What is clear, though, is that lead poisoning is not something you'd want to have. People with very severe lead poisoning tend to have major neurological changes - brain swelling leading to seizures and headaches, aggressive behavior, loss of short-term memory, and slurred speech - and a host of other problems, like anemia and constipation.

Did lead poisoning cause the fall of the Roman Empire? Probably not. Yes, there was increased lead production in the Roman Empire, which we know from histories, ecological sources (like ice cores from Greenland and peat bogs in Europe), artifacts, and now skeletons. But the data - few as they are - simply don't support a conclusion of high lead concentration in the entire population. More research of this sort is needed, of course, to examine the potential effects that anthropogenic lead had on the population of Rome and the Empire. Fortunately, more will be forthcoming from Gabii as I start biochemical analyses of those skeletons this year, so stay tuned!

Notes:

* Aufderheide and colleagues (cited below) did test 20 skeletons from Italy, including a few from the greater Rome area. However, this was not an in-depth study, in that the skeletons were from various places. They further note that they could not control for lead diagenesis, which may (or may not) have thrown off their measurements. Twenty years later, the technology for identifying lead concentration in skeletons is greatly improved. Aufderheide and colleagues found that skeletons from the Roman period (by which they mean the Imperial period) had much higher lead levels than in the previous centuries, which is consistent with our study and the understanding that lead working increased in this time period.

Further Reading:

References:

References:

A. Aufderheide, G. Rapp, L. Wittmers, J. Wallgren, R. Macchiarelli, G. Fornaciari, F. Mallegni, & R. Corruccini (1992). Lead exposure in Italy: 800 BC-700 AD. International Journal of Anthropology, 7 (2), 9-15 DOI: 10.1007/BF02444992.

J. Montgomery, J. Evans, S. Chenery, V. Pashley, & K. Killgrove (2010). 'Gleaming, white, and deadly': using lead to track human exposure and geographic origins in the Roman period in Britain. Roman Diasporas, Journal of Roman Archaeology, Suppl 78, 199-226.

C. Roberts and K. Manchester. 2007. The Archaeology of Disease. Cornell University Press.

T. Waldron. 2009. Palaeopathology. Cambridge University Press.

| Lead pipes from a Roman bath (Credit: Ad Meskens / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0) |

But let's start with some contemporary medical knowledge. Metabolic disorders can be caused by a lack of nutrients - a lack of vitamin C gives you scurvy, and a lack of vitamin D gives you rickets - but they can also be caused by an abundance of something, like too much fluoride, too much mercury, too much arsenic, or too much lead.

Lead is a heavy metal, one that isn't needed by the human body, unlike vitamins C or D. This element is found in the environment naturally, so we do expect to find some amount of lead in the skeleton of every person, ancient or modern. But, because of the physical properties of lead - it can be made into hard, sharp things - people have been using it for millennia and thus have been exposed to heavy metal toxicity for millennia as well. The dangers of lead actually weren't well known until the second half of the 20th century, which was when lead was taken out of things like paint and gasoline.

The main problem with lead - the reason that it's toxic - is that it interferes with normal enzyme reactions within the human body. Lead can actually mimic other metals that are essential to biological functioning. But since lead doesn't work the same way as those metals, the enzymatic reactions that depend on things like calcium, iron, and zinc are disrupted. The most damaging enzymatic reaction that lead affects is the production of hemoglobin, or red blood cell production, which can cause anemia. So doctors in modern times often find anemia in a person with lead poisoning. Lead is also particularly problematic because it stays in the body for a very long time once it's absorbed, inhaled, or ingested. Most of it gets deposited in the bones and teeth. Lead can be removed from the body, excreted through the kidneys and urine, but it's a very slow process without modern chelation therapy.

|

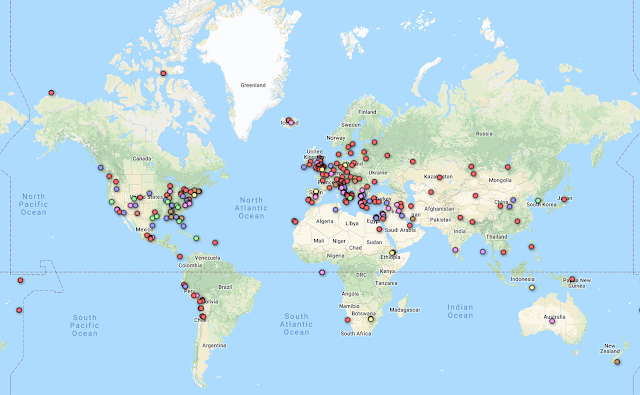

| Map of Imperial Rome and Suburbs (Map by K. Killgrove and P. Reynolds, 2013.) |

Some of the data from that article is below. The Romans are there in the middle. What you can see is that there are fairly low levels of lead in the pre-Roman periods in Britain (Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age) and the levels are lower in the post-fall of the Roman Empire (after 5th c AD). So what do those numbers mean on a scale of Normal to Lead Poisoned? Well, the modern recommendation by the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control is that children should not have more than 1 mg/kg of lead in their bones (or 10 ug/dL measured in blood). Back to the chart, where I've inserted a bright orange line at 1 mg/kg, and no one in the pre-Roman period is getting poisoned. The Imperial period is pretty special - we've got a person with lead levels over 20 mg/kg, which is 20 times higher than modern recommendations! In fact, this level is two times higher than the level the WHO considers "very severe lead poisoning."

|

| Lead concentration from skeletons from Britain and Rome. (Raw data from Montgomery et al. 2010, Tables 11.2, 11.3, 11.4.) |

The chart also shows the median human lead concentrations that I calculated for these groups. You can see a spike during the Roman period, and then median values drop in Britain. The post-Roman data can be broken down further into just post-Roman rule (5th-7th c AD, with a median of 0.39 mg/kg), early Medieval (8th-11th c AD, with a median of 1.93 mg/kg), and late Medieval (median of 4.69 mg/kg) (Montgomery et al. 2010, Table 11.4). The later Medieval period therefore shows an even greater use of lead than Imperial Rome, at least for these samples.

.gif) |

| Adverse effects of excess lead (Credit: Madhero88 / WikimediaCommons / CC-BY-3.0) |

Did lead poisoning cause the fall of the Roman Empire? Probably not. Yes, there was increased lead production in the Roman Empire, which we know from histories, ecological sources (like ice cores from Greenland and peat bogs in Europe), artifacts, and now skeletons. But the data - few as they are - simply don't support a conclusion of high lead concentration in the entire population. More research of this sort is needed, of course, to examine the potential effects that anthropogenic lead had on the population of Rome and the Empire. Fortunately, more will be forthcoming from Gabii as I start biochemical analyses of those skeletons this year, so stay tuned!

Notes:

* Aufderheide and colleagues (cited below) did test 20 skeletons from Italy, including a few from the greater Rome area. However, this was not an in-depth study, in that the skeletons were from various places. They further note that they could not control for lead diagenesis, which may (or may not) have thrown off their measurements. Twenty years later, the technology for identifying lead concentration in skeletons is greatly improved. Aufderheide and colleagues found that skeletons from the Roman period (by which they mean the Imperial period) had much higher lead levels than in the previous centuries, which is consistent with our study and the understanding that lead working increased in this time period.

Further Reading:

- The Bones of Martyrs? by Kristina Killgrove, Past Horizons, 5/25/11

- Lead Poisoning and Rome by James Grout, Encyclopaedia Romana

- Saturnine Gout among Roman Aristocrats: Did Lead Poisoning Contribute to the Fall of the Empire? by Jerome Nriagu, New England Journal of Medicine, 3/17/83

- The Myth of Lead Poisoning among the Romans: an Essay Review, by John Scarborough, Journal of the History of Medicine, 1984

- "Line on the left, one cross each:" the Bioarchaeology of Crucifixion by Kristina Killgrove, Powered by Osteons, 11/4/11

A. Aufderheide, G. Rapp, L. Wittmers, J. Wallgren, R. Macchiarelli, G. Fornaciari, F. Mallegni, & R. Corruccini (1992). Lead exposure in Italy: 800 BC-700 AD. International Journal of Anthropology, 7 (2), 9-15 DOI: 10.1007/BF02444992.

J. Montgomery, J. Evans, S. Chenery, V. Pashley, & K. Killgrove (2010). 'Gleaming, white, and deadly': using lead to track human exposure and geographic origins in the Roman period in Britain. Roman Diasporas, Journal of Roman Archaeology, Suppl 78, 199-226.

C. Roberts and K. Manchester. 2007. The Archaeology of Disease. Cornell University Press.

T. Waldron. 2009. Palaeopathology. Cambridge University Press.

Comments

" Water conducted through earthen pipes is more wholesome than that through lead; indeed that conveyed in lead must be injurious,g because from it white lead is obtained, and this is said to be injurious to the human system. Hence, if what is generated from it is pernicious, there can be no doubt that itself cannot be a wholesome body.

This may be verified by observing the workers in lead, who are of a pallid colour; for in casting lead, the fumes from it fixing on the different members, and daily burning them, destroy the vigour of the blood; water should therefore on no account be conducted in leaden pipes if we are desirous that it should be wholesome. That the flavour of that conveyed in earthen pipes is better, is shewn at our daily meals, for all those whose tables are furnished with silver vessels, nevertheless use those made of earth, from the purity of the flavour being preserved in them."

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio:

de Architectura, Book VIII 6. 10 - 11.

Lead is cheap and easily worked into pipes; it has only comparatively recently been replaced in our own cities[UK]. [I was told that you detect areas with lead water infrastructure in the education statistics [IQ]]

And the earliest probable description of lead poisoning (from which our article title gets its name) is in the Alexipharmaca of Nicander (II.74ff), who speaks of lead as "gleaming, white, and deadly" and describes many of the symptoms of lead poisoning. Yet there is no indication that lead poisoning was endemic - either in the population as a whole or in the aristocracy, who would have had better access to sapa, lead pipes in their house, etc.

So, in spite of the knowledge that lead (pipes) could cause problems for the human body, the Romans continued to use it for everything from pipes to wine sweetener. The sapa/defrutum would be the most problematic, since the Romans were actually just drinking it. But since they diluted their wine with water, that may have saved many of them from lead poisoning.

Still, the charts show that plenty of people had lead levels in their bodies well over modern recommendations. It'll be interesting as more data come out to see just how much lead people of Rome had in them, and perhaps settle this question of lead poisoning once and for all...

I recall another problem, thiamine, the B vitamin, the lack of it can cause violent symptoms and the overabundance apparently can be paradoxical, the body gets rid of it all. Cited in some literature in health effects of Japanese fishing culture food is all rice and fish.

I always wondered if Rome ever had sucrose all their sweeteners "sugars" were probably fructose?

Nriagu, Jerome O. Lead and lead poisoning in antiquity. New York: Wiley, 1983.

Nriagu, J.O. “Saturnine Gout Among Roman Aristocrats.” New England Journal of Medicine 308, no. 11 (1983): 660–663.

That might explain why rates are comparably high (pre-C8th), but only a few sample cases have 10mg/kg or higher.

There is also some discussion concerning diagensis and lead content in Roman skeletons.

De Muynck, D., C. Cloquet, E. Smits, F.A. de Wolff, G. Quitté, L. Moens, and F. Vanhaecke. “Lead Isotopic Analysis of Infant Bone Tissue Dating from the Roman Era via Multicollector ICP–mass Spectrometry.” Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 390, no. 2 (2008): 477–486.

Lead pollution was rampant in the greater Rome area. There's no reason to think that only the upper class was affected by lead poisoning. Of course, more research is needed - between the two studies, only about a dozen skeletons have been tested for lead levels.

I'll have to look into the lead diagenesis article you mention. The title suggests isotopes, but lead poisoning is inferred from concentrations. Two different measurements. Anyway, will check it out!

my second guess is that on some level it could correlate with age, since human's have poor led filtering capabilities.

It has recently been demonstrated that the decline in violent crime since the 70s can be explained only by the decline in leaded gasoline. http://www.motherjones.com/environment/2013/01/lead-crime-link-gasoline

And all the concoctions that we mix with water to "flavor it."

How "smart" (capable) were we in the past? There are some hints...look up videos on Youtube - 60 Minutes Endless Memory, and Human Calculator - Scott Flansburg or Rudiger Gamm. Also a series called Memory Masters. Also Orlando Sorrell.

Anecdotally, in the past many could recite long poems / oral history, but not we have to write a lot of things down because our memory sucks.

We think we are getting smarter and more capable with all of our "technology." But a lot of our technology is just making up for our devolution over many generations.

Chemicals and harmful EMF (mobile phones/cell towers, wi-fi/wireless, etc...) affecting our cell development, and increased exposure to artificial light.

There wasn't one single failure point for Rome, and there isn't one single failure point for our modern society.

To where the only way to do this accurately would be to find those Romans who actually consumed water that passed through lead plumbing regularly.