This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

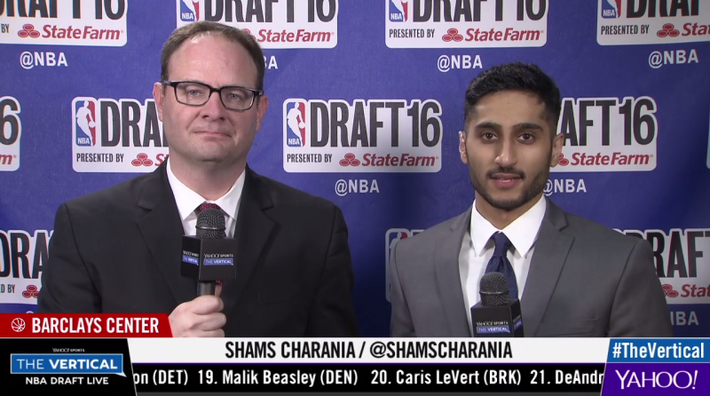

Shams Charania arrived at a restaurant in downtown Chicago last month just as his colleagues and sources around the National Basketball Association told me he would: running a bit late, phone in hand, AirPods plugged into both ears. “It’s very hard to have lunch with Shams,” a former NBA executive had warned me. The issue is holding his attention. Charania works for The Athletic, the sports website that is now business-critical to the future of the New York Times and where his title is senior NBA insider. The job involves staying in near-constant contact with hundreds of agents, executives, players, and hangers-on throughout the NBA in order to be in position to break basketball news big and small to his 2.1 million followers on X (the former Twitter) — more than any other reporter at the Times. When we met, Charania had taken a Lyft from his home in the Chicago suburbs because driving would have prevented him from texting and the train wasn’t an appropriate place to take a call from, say, the general manager of an NBA team whose name popped up on Charania’s iPhone shortly after he sat down. At one point, Charania set down a piece of toast to type out a text with his right pinkie to avoid smearing the screen with the strawberry jam on his thumb. “I didn’t even realize I was doing that,” he said when I pointed it out. “I’ll do anything to get the text off. I’ve used my nose before.”

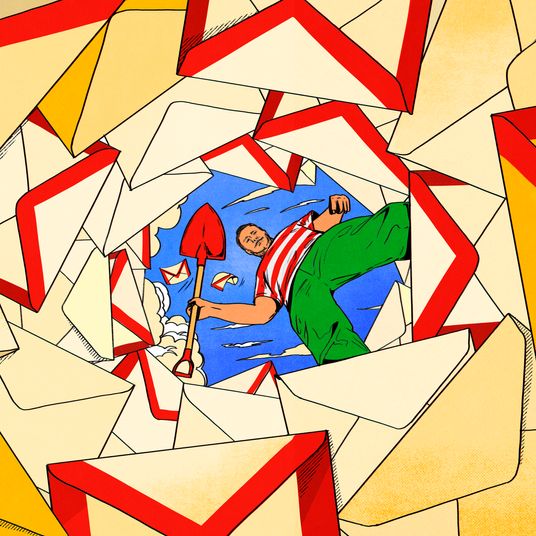

It was mid-September, a rare slow moment in the NBA calendar, but Charania was keeping tabs on a pair of extended dramas involving two star players, Damian Lillard and James Harden, who were both demanding to be traded by their respective teams. “If I take a day off, never mind a week off, I put myself behind the eight ball,” Charania said. At the restaurant, he wore all black — suede jacket with a hood, sweatshirt, skinny pants — and a pair of John Geiger sneakers that were white save for what appeared to be a coffee stain. Charania drinks only two cups a day but exudes caffeination; his legs shook constantly under the table, and I lost track of how often he reached for his phone, which had 125 unheard voice-mails, 72,443 unread emails, and an unceasing stream of texts, many of which he responded to as they came in. He averages 18 hours of screen time a day and was proud of how far that number had dipped on a recent vacation to Portugal with his family, even if he had continued tweeting minor news — “Skal Labissiere has agreed to a partially guaranteed one-year deal with the Sacramento Kings” — throughout the weeklong trip. “I prefer the poolside sit-and-do-nothing vacation, so I can still be on my phone as constant as I wanna be,” Charania said. “But did it get to, like, 14 hours? Yes. Did it get to, like, 12 or 13 hours some days? Yes. I think that’s a win.”

Charania, who is 29 and has been a working NBA journalist since he was a teenager, is an omnipresent figure in the lives of everyone in the league. Earlier this year, Steve Kerr, the head coach of the Golden State Warriors, was so miffed that Charania had leaked a tactical change the Warriors planned to make that he suggested Charania had a mole in the locker room. Kevin Durant once said on his podcast that it seemed like Charania was in the CIA. “Shams a creep, yo,” Durant said of Charania’s ability to gather intelligence. When there is big NBA news to be broken, the only question anyone has is whether they will learn about it from Shams or Woj.

Woj is Adrian Wojnarowski, ESPN’s own senior NBA insider and Charania’s onetime mentor. Wojnarowski gave Charania his first big job in journalism and helped train him in the murky reportorial art of becoming an “insider” — among the best-paying and most intrigue-filled jobs in journalism — only to have Charania become his chief rival in the race for NBA scoops. “These two guys who never even played varsity basketball dominate information flow in the NBA with a direct line to the commissioner, to agents, to owners, to everybody, because of platforms they’ve created basically out of thin air,” one longtime NBA front-office executive told me. Charania and Wojnarowski have become celebrities in their own right — Wojnarowski has more than 6 million X followers — by serving as vessels for the daily stream of news that holds NBA fans’ attention even (and perhaps especially) when there aren’t any games being played.

“The NBA’s primary cash crop is drama,” one league source told me. “On some level, Woj and Shams are the writers of the soap opera. Who gets shot? Who leaves who? Who falls off the building? It’s the same as, Who wants out of which team? And, of course, Who’s the villain?”

While Wojnarowski, who is 54, worked his way up the newspaper-reporting circuit before pivoting much of his energy to Twitter, Charania is a pure creation of the turbulent past decade in sports media. He has never known reporting without iPhones and DMs and is far more famous for his constant tweeting than for any story he has ever published, in part because his writing is so notoriously clunky that the sports website Defector named an annual award for inscrutable prose after him. In addition to his work for The Athletic, his résumé is a laundry list of modern-media arrangements his predecessors could never have imagined: He has side gigs with FanDuel, a sports-gambling company; Stadium, a digital-video network owned by the owner of the Chicago Bulls; and AT&T, for whom he films commercials about how much he uses his phone. While many of his colleagues rue Charania’s success and what it says about their industry, they also respect his hustle and acknowledge that his quick rise is indicative of the times. “You don’t need to be able to write when the currency is the scoop,” one of his colleagues told me.

This summer, the Times announced that it was shuttering its sports department and replacing it with Charania and his co-workers at The Athletic, which the Times had purchased last year for $550 million. The decision jolted the sports-media world and raised Timesian hackles about Charania in particular, as Times journalists questioned how the instantaneous, anonymously sourced, transactional reporting that he specializes in fit in at the paper of record and whether his arrangement with a sports-gambling company opened him up to the kind of ethical conflict it tries to avoid. “He is now a vital part of a de facto sports section for a newspaper that would never hire him,” a former Times reporter told me.

But as sports journalists debate whether Charania represents the industry’s decline or its inevitable future, the question for the Times may be less about whether it can turn Charania into a proper Timesman and more whether it’s willing to adapt to the conflicts that come with competing in modern sports media. The question for the NBA is what to do about the mole in the locker room.

When I asked people who work in the NBA what it was like to have Charania chase them for a scoop, especially early in his career, they described it as an experience somewhere between irritating and a pain in the ass. “He was calling all the time — like, nonstop — to get any little morsel of information,” Jerry Colangelo, who ran USA Basketball throughout the 2010s, told me. It was like being doxxed, except that all of the calls were coming from a single person. “He’ll text you 20 times in an hour, to a point where he wears guys down, and you just want him to fucking leave you alone,” the longtime NBA front-office executive told me. Even when there wasn’t any news to break, he was still in touch. A current executive told me he gets a “Happy Father’s Day” text from Charania every year, which he presumes is sent to every dad in the league. A third recalled a message wishing him a “Happy Labor Day.” “The only other person who texts me ‘Happy Labor Day’ is my union buddy,” the executive said. (Almost everyone I spoke to in the NBA declined to go on the record, partly because talking anonymously has become the default way of communicating in the league and partly because they feared crossing the reporters who dominate its coverage.)

When I mentioned the comments about his relentlessness to Charania, he acknowledged that they were fair. Charania estimates that he sends more than 500 texts, calls, and emails a day. “My mind is consumed by, What can I do today to get information that I didn’t have yesterday? ” he told me. “It consumes everything I do.” It was only two years ago that Charania moved out of his parents’ home in the Chicago suburb of Wilmette; he bought a house one town over to stay close to his mother. He goes on dates but doesn’t understand how his colleagues with spouses or children manage to do their jobs.

Like many sports journalists, Charania started writing about basketball because, at five-foot-nine, he wasn’t good enough to have a career playing it. He made the freshman team at New Trier High School but was cut the following year. (Charania still plays but stopped for six months after missing an urgent tip about the Boston Celtics potentially firing then-coach Ime Udoka during a pickup game last year.) After getting cut, Charania opened a Twitter account — @SCharania94, the year he was born — and reached out to an editor for a local blog network run by the Chicago Tribune to ask if he could write about the Bulls. The editor’s only question was whether he had permission from his mom and dad. His parents, who immigrated from Pakistan and worked in medicine, had another question: Have you thought about medical school? But Charania was a distracted student — “C’s get degrees, that was really my philosophy” — and much of his middle- and high-school class time was spent refreshing HoopsHype and RealGM, early internet websites that allowed basketball obsessives to track the rumors, deals, and intrigue that weren’t quite worthy of SportsCenter but were being constantly whispered about around the league. “The audience for this stuff is me,” a veteran NBA agent told me. “Guys who live and breathe this shit because they have nothing else in their lives.”

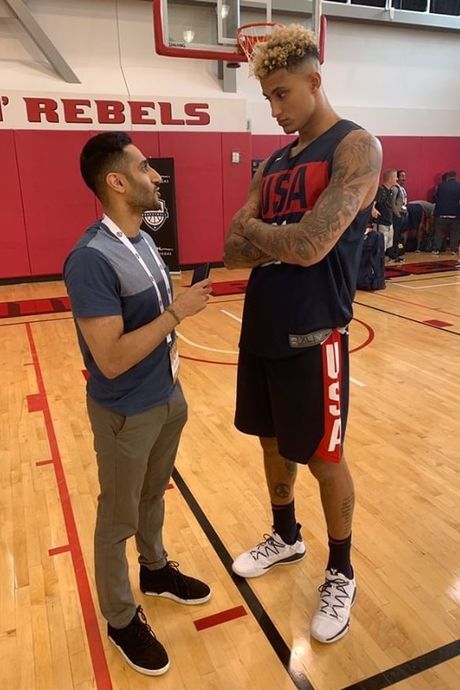

As a teenager, Charania started writing for RealGM and brought an unusual precociousness to the job. When the Bulls wouldn’t give him a press pass because of his age, Charania started driving his mother’s Camry to cover NBA games in Milwaukee and Indianapolis, racing to make it back to Chicago for class. (He racked up enough speeding tickets to get his license suspended.) But no one could tell how old he was through the phone, and Charania started cold-texting NBA agents whose numbers he found online, hoping to land interviews with their players. Bernie Lee, who now represents All-Stars Jimmy Butler and Ben Simmons, remembers Charania asking to interview one of his clients, who was a minor bench player for the Bulls. “I suggested after practice at 1:30, and he was like, ‘I’m in school,’” Lee told me. “I said, ‘Come on, I blew off classes in college all the time,’ and he said, ‘No, I’m in high school.’”

Charania aspired to write the kind of in-depth, longform stories that had defined sports-media success, but he was getting into the industry at a moment when the relationship between reporters and their subjects was changing. Sports leagues were selling wildly lucrative contracts for the rights to televise live sports, which made them business partners with some of the media outlets tasked with covering them. Social media also gave players and teams the chance to reach an audience without ever talking to a journalist. “The people in the business were feeling a tremendous amount of pressure to basically favor-trade for access,” Henry Abbott, who covered the NBA for ESPN at the time, told me. “It was moving to a Hollywood model because the same agencies were getting involved in sports: CAA and other very powerful global agencies were accustomed to the media kowtowing in certain ways.”

Meanwhile, covering the off-season was becoming as crucial as reporting on the games themselves. In 2010, LeBron James turned what had traditionally been a quiet process — choosing whether to stay on his current team or join a new one — into a prime-time special called The Decision, which filled sports media with conjecture and gossip for weeks before and after it happened. (The NBA would eventually move the start of free agency from midnight up to 6 p.m., launching the frenzied burst of player signings in prime time.) For most beat reporters, the prize was no longer a probing profile of an athlete or a locker-room-scorching column but nuggets of information gleaned from front offices and dispensed for podcasters and ESPN talking heads to chew up. Insiders littered their stories with “league sources,” a phrase vague enough to refer to practically anyone from a ball boy to the NBA commissioner. In 2014, Bryan Curtis, who covers sports media for The Ringer, compared the rise of sports insiders to the emergence of Nikki Finke in Hollywood. “She became a player by scooping the hiring and firing of executives that 99 percent of the public had never heard of,” Curtis wrote. “It wasn’t the transactions per se that made people perk up. It was the idea that Finke purloined info from inside a closed system.”

As Charania built up his contacts, agents started leaking him minor scoops that more established NBA reporters wouldn’t bother with: Jannero Pargo’s ten-day contract with Atlanta, Quincy Douby heading to China to play for the Shanghai Sharks. “Shams barely felt like a real person,” a fellow NBA reporter told me of Charania at the time. “It almost felt like he was a bot.” Charania’s big break came in 2014, when he was a 19-year-old sophomore at Loyola University Chicago. He was sitting in his room watching a movie when an email came in from a source with a genuine scoop: All-Star forward Luol Deng was being traded from Chicago to Cleveland. Charania felt a rush of adrenaline as he posted the news, stunning other NBA reporters. ESPN’s Brian Windhorst tweeted what he thought was a scoop before realizing that Charania had gotten to it two minutes before: “Hat tip to @ShamsCharania” — he had professionalized the handle — “looks like he got the Deng news out just before I did.” Windhorst, who had covered a young LeBron James, started referring to Charania by the same nickname James had been given: “the Chosen One.”

But in the world of NBA scoops, the king was still Adrian Wojnarowski, who had left a successful career as a newspaper columnist to join Yahoo Sports in 2006, just as digital outlets started to challenge traditional ones. In the 2010s, Wojnarowski’s Twitter feed became the place where people in the NBA found out what was happening, sometimes on their own team. His most league-disrupting scoops on blockbuster trades or free agent signings came with their own hashtag: #WojBomb.

Charania wasn’t yet dropping any #ShamsBombs, but in 2015, when he was a junior in college, Wojnarowski hired him to join the NBA team at Yahoo. After the Deng trade, Wojnarowski had called Charania “the best young reporter” in the business; Charania, meanwhile, referred to Wojnarowski as “the blueprint to sports journalism, period.” Wojnarowski took Charania under his wing and predicted that he would become “the news breaker in the NBA” — in other words, that Charania would supplant him.

In 2017, ESPN finally got so tired of having to cite Wojnarowski’s scoops on the network’s scrolling news ticker that it decided to hire him. “It had to do with brand and wanting to be known as the most important news organization in sports,” John Skipper, who was president of ESPN at the time, told me. “But if I’m a tiny bit cynical, it was also pride. We wanted to be first, and we wanted to win.” Charania was still in college with a year left on his Yahoo contract, but John Kosner, an executive at ESPN, told me Charania could have joined Wojnarowski at ESPN after that. But without Wojnarowski, who has a reputation for being competitive even within his own newsroom, Charania thrived. Some of his young agents and junior front-office contacts were now in bigger jobs, and Charania was suddenly competing for the biggest scoops in the league. “Adrian sort of created Frankenstein’s monster,” Frank Isola, who has worked with both Charania and Wojnarowski, told me. (Wojnarowski declined to comment for this story.)

Instead of joining ESPN, Charania took a job at The Athletic, a website founded in 2016 by Alex Mather and Adam Hansmann, both of whom were from the tech world. Venture capital had come for sports media. The Athletic gobbled up reporters across the country in an effort to create a digital-only, nationwide network of local sportswriters. In 2017, the Times sports section published a story about the site that now feels like an omen. “We will wait every local paper out and let them continuously bleed until we are the last ones standing,” Mather said. “We will suck them dry of their best talent at every moment. We will make business extremely difficult for them.”

The Athletic wasn’t hiring Charania to deliver award-winning feature stories. In the first sentence of an article describing Kyrie Irving’s demand for a trade from the Brooklyn Nets, Charania unleashed a cascade of metaphors: “A league-altering domino fell and shook up the marketplace, causing a shockwave across the league and an arms race to get underway.” Last year, he wrote that another player’s skill set “has become incredibly valued toward winning.” Readers and other journalists noticed that Charania’s stories were often written in an oddly passive voice that seemed to value protecting his sources over projecting clarity. In a controversial story from 2021, Charania cited anonymous sources to explain Irving’s decision not to get a COVID vaccination, writing that “those who know Irving understand he is not driven right now by money, nor cares for inheriting more, but rather the stand for larger issues in his mind that need his support.” That year, Defector started giving out its annual Shamsy Award for clumsy writing: “The Shams Charania Award for Excellence in Divulging of Information Through Syntax Comprehended by Many.” In a fitting valediction to an era in sports journalism, last year’s Shamsy went to Woj.

At The Athletic, some employees expressed skepticism about Charania’s value. “It was hard to wrap your mind around, ‘Wait, 90 percent of his value is on another platform?’” a former executive at The Athletic said. Charania’s colleagues there told me he was an eager teammate willing to share scoops and help local beat reporters with his nationwide network of sources. But his Twitter following was what the young start-up was really after. “There’s basically a marketing cost priced in,” a former business-side employee told me of Charania’s salary. “Every time one of Shams’s tweets gets projectiled around the world in front of tens of millions of people, you’re saving tons of money.”

Charania had become a brand. In addition to his work at The Athletic, he signed a contract to appear on an NBA-focused show for Stadium, a digital-video network. (A former Athletic executive told me Charania was expected to tag @theathletic before @stadium on X.) And part of the brand was his rivalry with Wojnarowski, which became entertainment itself for NBA fans, who responded to their scoops by superimposing their faces onto NBA players dunking on each other. A sample Reddit post: “I Analyzed Over 2000 of Woj and Shams Tweets to Determine Who Reported More News This Year.”

To hear “league sources” tell it, Wojnarowski has a grip on many of the NBA’s front offices, while Charania has more of a foothold among agents and even many players. But they are often competing for the same scoops from the same people. “A reporter will develop a relationship for months, and those months earn them the first text — which is 40 seconds ahead of the second text,” another NBA reporter told me. In 2021, Ethan Strauss, a former ESPN reporter who now writes a Substack about sports, published a document Wojnarowski was distributing to potential sources highlighting that his social-media reach dwarfed that of other NBA journalists, including Charania. The implication was that leaking to anyone else would do a disservice to yourself and your client — and that Wojnarowski was worried about losing ground.

Today, Wojnarowski and Charania are locked in something of a cold war and rarely acknowledge each other in public. “Maggie Haberman will mention Josh Dawsey, or vice versa, but you don’t see that in the NBA,” an NBA reporter told me. Wojnarowski deleted his early tweet endorsing Charania as a promising young reporter; at ESPN, one of Wojnarowski’s colleagues told me, Charania is “he who shall not be named.” When I asked Charania about the status of his relationship with his old mentor, he asked what I had heard, then turned to his phone and sat in silence for a full 45 seconds before saying that it had been “a blessing” to work with Wojnarowski and the rest of the team at Yahoo.

Wojnarowski and Charania have become so dominant in the race for scoops that most other reporters who cover the league told me they have stopped trying. “I talk to the same agents, the same GMs, but I never even try to break news,” another ESPN reporter told me. “I know it’s already promised to one of them — like they’re a wire service.” In an attempt to keep up, Ken Berger, who was a national NBA reporter at CBS Sports, started using Google Voice to send texts because it allowed him to send separate identical messages to five people at once. “I could text three agents and two front-office people in five seconds, and I’m still getting beat,” Berger said. He eventually left NBA media for good to run a fitness studio in Queens. To help his old colleagues, he started a personal-training program tailored to helping NBA journalists survive the unhealthy lifestyle the job entailed.

In 2021, Bernie Lee, the agent who first met Charania when he was in high school, got a notification on his phone that Charania had reported on tension between one of Lee’s clients, Jimmy Butler, and his team, the Miami Heat. Lee thought the report, which centered on Butler being demanding, was misleading — “Jimmy’s hard on people? No shit!” — and took to Twitter himself to respond. “Shut the fuck up you click bait, ambulance chasing, dirt bag piece of shit,” Lee wrote of Charania. “No one has told you this because this is not reality. Go find someone’s assistant to text abt an MRI or some other human calamity you want to be 1st on.” Lee told me he objected partly to the story itself but also to the media environment in general. “Players are experiencing the world through their phones and consuming this like everybody else, and because these guys are consuming nothing but garbage about themselves, I’m seeing guys be unable to have an accurate sense of themselves,” Lee said. “It’s not solely Shams’s fault. He just happens to be a ringleader of a really shitty circus.”

Plenty of people in the league expressed a desire to wish away the insider era and the constant rumor cycle that comes with it. NBA news didn’t use to flow so freely. Reporters had to call a team’s office and persuade a receptionist to connect them to the general manager, who might be the only person who really knew what trades or signings were about to happen. If news leaked, you knew where it was coming from. Now, NBA staffs have ballooned in size with analytics teams and salary-cap experts, and everyone is a text away. “Prior to Twitter, and the birth of these breaking-news guys, the league was all about how you keep your information confidential,” a longtime front-office executive said. “Now you have to operate off the assumption that the minute you utter a word about something, it’s gonna get out.” With reporters chasing stories around the league and reporting rumors day-to-day, one GM estimated that between 10 and 20 deals get blown up because of leaks every year. “I can’t tell you the number of times a potential trade leaks out, and you get a call from the other GM who says, ‘My fucking owner doesn’t like the terms,’ or ‘My owner wants this player, not that one,’” the longtime front-office executive told me.

Charania and Wojnarowski typically aren’t the ones blowing up these deals ahead of time. If they hear about a trade that isn’t quite finalized, and the team’s GM asks them not to report it just yet, both Charania and Wojnarowski are often willing to sit on the story on the expectation that they’ll get the scoop when it’s done. Everyone I spoke to in the NBA said the trust and comfort they felt around Charania and Wojnarowski were key to their success. “The thing you learn very quickly is: The reporters have everything,” one NBA executive told me. “Everyone wants to always pretend that they’re not talking. But everyone is talking.”

In part, this was PR 101: Team executives want to leak their side of the story, because if they didn’t leak, the other side would anyway. For agents, both Charania and Wojnarowski have taken to reporting contract signings in recent years by mentioning not only the agent who negotiated the deal but tagging their agency on social media — free publicity for agents hoping to attract potential clients. “You would never see a tweet from a D.C. reporter saying, ‘Fantastic deal negotiated for water rights on the Colorado River’ and then the names of the undersecretaries who made the deal,’” a former Times reporter told me.

But many agents and executives said there were less obvious and more private reasons to work with Charania or Wojnarowski. They can give you as much as you give them. “Woj made me a better agent,” Warren LeGarie, a longtime agent who represents coaches, told me. “If I was trying to get in on something, he would tell me, ‘You’re wasting your time, that deal is done.’” Another agent told me that if he needed to know, say, how many open roster spots a team had to see if he could land a job for one of his players, he could text Charania, who would find out and get back to him. Teams can also use insiders as middlemen: If one GM wants to trade a player while maintaining deniability about their desire to do so, they might let one of the reporters leak it quietly around the league. “They become like Henry Kissinger — Nixon can’t get on the phone with Brezhnev, but Shams or Woj can,” the longtime front-office executive said. “They can be used to facilitate a conversation that is beyond salvation. It’s like having a marriage counselor.”

Every reporter navigates a gray area with sources, but the relationships Charania and Wojnarowski have appear especially cozy. “The thing that changed is they became double agents,” John Skipper, the former ESPN president, told me. “They call people and say, ‘Tell me what you’re up to,’ and the quid pro quo is, ‘I’ll tell you a little something I’ve heard.’ You’re suddenly on the road to being part of causation if somebody acts upon something you share.” The longtime front-office executive told me that information from insider reporters could even help a GM save a buck. “Woj or Shams might say, ‘Hey, don’t get levered up on Player X; he’s not gonna get an offer from his team,’” the executive said. “There are times when they have information that has prevented me from making a mistake in terms of the magnitude of a contract offer or the inclusion of a specific asset in a deal.”

I found conflicting views throughout the NBA about Charania and Wojnarowski and the role they play in the league. Many people appreciated their usefulness or enjoyed the game. “Some people treat this stuff like nuclear secrets, but this is sports,” one team executive told me. “Trying to figure out what another team is doing is fun.” But many NBA journalists, in particular, worried about the stories that weren’t getting told when the biggest reporters in the game were so beholden to the league and everyone in it. “It’s not that this needs to fit Thomas Jefferson’s view of the press, but it’s become the opposite of that,” Henry Abbott told me. “NBA fans see the pinnacle of journalism as breaking a transaction: ‘It’s Christmas. What trade do you have for me?’ It’s almost like Shams got them the trade — he’s Shamsta Claus.”

When the New York Times bought The Athletic last year for $550 million, it made Charania and his Athletic colleagues a core part of the company’s business future. The purchase was the paper’s largest since buying the Boston Globe for $1.1 billion in 1993 and cost nearly 20 times what the Times had paid for Wirecutter in 2016. The Times could have spent a sliver of that hiring the best reporters from The Athletic to beef up its own sports coverage, but the acquisition was about something else. The Athletic has never been profitable and continues to lose money, but like Wordle, which the Times acquired in 2022, the site is meant primarily to serve as a funnel sluicing readers toward the increasingly expensive Times subscription bundle.

The strategy is something of a throwback. Newspapers were the original bundle with different readers subscribing for the news, the comics, and sports; The Athletic was founded on the premise of unbundling sports; now, the Times is trying to rebundle it. The Athletic had 1.2 million subscribers when the Times bought it, and only one out of ten were already paying for the Times, meaning The Athletic offered an opportunity to reach demographics (men who live between the coasts, for one) it has traditionally struggled to bring in. The acquisition nudged the Times past its goal of 10 million subscriptions, a metric it has now increased to 15 million individual subscribers by 2027. The Times believes there are “some 135 million English-speakers” who might pay for its services, 17 million of whom are willing to pay the Times for sports coverage.

When I spoke to business-side employees at The Athletic, several told me that Charania had been among the biggest subscription drivers in the company’s history. While local beat reporters in Cleveland or Dallas could keep Cavaliers and Mavericks fans subscribing month after month, Charania was the one who got them in the door — a funnel into a funnel. The Times’ decision to shutter its sports department this summer and replace it with coverage from The Athletic both online and in the print newspaper made it clear how central it sees Charania and his colleagues in helping to bring in new readers. While the sports section had focused on investigations and human-interest stories, it had largely ignored the coverage for hard-core sports fans that The Athletic specializes in. “We bought the Athletic because it was the best at serving fans — people who care deeply about sports,” said David Perpich, the Times executive who oversees The Athletic. Perpich said the Times sees similar business value in breaking news about NBA transactions and news about the White House — politics obsessives want the latter, sports obsessives want the former, and the Times aspires to feed them both.

Some readers seem ready to welcome the change. Last year, Ralph Nader complained that the “Sports” section had a “full page on some soccer stadium in Milan, Italy, 2/3rds of a page on a soccer team in England and nothing about the hometown @Yankees or @Mets games.” The publication seems to be doubling down on insiders: The Athletic recently poached Dianna Russini, an NFL insider from ESPN, and according to former Athletic executives, came close this year to hiring Fabrizio Romano, who has become the predominant scoop machine for international soccer with nearly 19 million X followers.

But there is skepticism among Times staffers about whether the company’s investment in The Athletic will pay off: How many new readers will come to the Times looking for both NBA mock drafts and Sam Sifton’s recipe newsletter? Since the acquisition, there has been tension between both staffs. The Athletic writers have office space in the Times’ New York headquarters, but on a different floor from the newsroom. Times staffers have complained that some of The Athletic’s work, and Charania’s in particular, isn’t up to the Times’ journalistic standards. Perpich rejected this critique. “What’s important is that when we’re putting it out, we can stand behind it,” he said. (For their part, multiple Athletic employees told me they were similarly unimpressed by their new colleagues: “You get to the Times, and think, They employ the best of the best, they’re gonna run circles around us, and then you get there and realize, Oh, they’re just like us.”) The Times’ decision to replace its unionized sports staff, all of whom were moved to other departments, with the nonunionized Athletic unleashed even more angst. The Times’ union has filed a grievance, and an arbitrator will consider the paper’s argument that The Athletic, which it owns, is merely a subcontractor, akin to Getty Images or the Associated Press. No one is holding out much hope the sports department will get reincarnated; a unionized Athletic seems more likely.

In August, roughly 200 staff members at the Times sent emails to A. G. Sulzberger, the newspaper’s publisher, and several members of its masthead, protesting the decision to shut down the sports department. Among the most pointed was a letter from Emily Bazelon, a staff writer for the Times Magazine who typically covers gender and the law. Bazelon wrote specifically to object to the fact that the Times was “allowing reporters who now effectively cover sports for the NYT to work for a sports betting company.”

She didn’t mention Charania by name, but it was clear whom she meant. Last year, Charania became a FanDuel partner, appearing on its cable network and posting about the company’s sportsbook on social media. The Times wanted to keep Charania from leaving for another job, but according to multiple people with knowledge of his contract negotiations, it couldn’t afford the going rate for his services. In addition to offering Charania more than $600,000 a year — significantly more than the paper’s top reporters make — the Times allowed him to take on the side deals with both Stadium and FanDuel. (His total compensation from various sources is now well into seven figures; neither Charania nor the Times would discuss his pay.) “The blow to our collective integrity is real,” Bazelon wrote. “It’s deeply unsettling to many of us and just not worth it.”

The FanDuel arrangement had already come under fire in June, after Charania tweeted a few hours before the NBA draft that there was “serious momentum” toward the Charlotte Hornets selecting a player named Scoot Henderson, only for Charlotte to choose a small forward named Brandon Miller instead. (Wojnarowski took the occasion to send a victory tweet: “All along, the entire Charlotte Hornets organization has been all-in on Brandon Miller.”) Many gamblers had placed bets based on Charania’s reputation and in turn lost money to FanDuel, the company that employs him.

No one I spoke to accused Charania of anything intentionally untoward. FanDuel doesn’t get his scoops beforehand, The Athletic doesn’t allow him to gamble on the NBA, and Charania says he doesn’t gamble at all. But a news reporter partnering with a gambling company felt icky. Several Times employees who have worked on the integration of The Athletic said that while it wasn’t the best look, it was also the price of doing business in modern sports media. ESPN recently signed a $2 billion deal with a different gambling company to launch its own sportsbook.

And the FanDuel arrangement was the kind of compromise the Times has occasionally made to keep its stars in-house. The paper has long had a dual-class hierarchy where marquee writers are allowed to do outside work that most staffers aren’t, and several employees compared Charania’s arrangement with FanDuel to that of Andrew Ross Sorkin, who covers finance while hosting CNBC’s morning show Squawk Box. While some of the complaints I heard from Times staffers were based in journalistic principle, many of them suggested an annoyance that they weren’t able to pursue similar opportunities.

Charania and I met for breakfast the day after the Times’ sports department shut down for good. When I asked Charania about the drama, he was unmoved. He stood by his reporting during the draft, although he would discuss the details only off the record and saw his connection to FanDuel as irrelevant to the news he reported for The Athletic. As for the Times infighting, he wanted to stay out of it. “In my mind, I work for The Athletic,” he said. Then again, a few days later, he proudly posted a photo on Instagram of his first article in the newspaper, on page B9 — the first time he’d had a story published in print since his high-school newspaper.

It’s possible to follow Charania’s career over the past decade and trace the shifts in sports media — from blogging, to tweeting, to a venture-capital-funded start-up, to being gobbled up by the Times, to an embrace of gambling. As for what’s next, Charania is loath to prognosticate. He has a tendency to revert to the practiced media-trained-speak of an athlete in a postgame press conference. “I just have tunnel vision,” he told me on several occasions. The uncertainty of Twitter’s transition to X, and what role it might play in the future of sports journalism at a time when social media has stopped driving traffic to websites, wasn’t something he had spent much time considering. “All I can do is keep my head down and focus on myself,” he said. When I asked if he might ever write a book, he said maybe, well into the future. There were certainly a lot of stories he couldn’t tell now without imperiling the next scoop.

While Wojnarowski has shared a fantasy with colleagues about one day taking his phone and throwing it into the sea, neither he nor Charania has shown much sign of slowing down. “There are stories where I’ll be dealing with one of them,” an NBA executive told me. “And I’ll just think, Look at everything you’ve accomplished, and all the money you’ve made — and you’re still sweating this minor transaction.” After breakfast, Charania hopped in another Lyft, tapping out texts along the way to the United Center, where the Bulls play, to tape a segment for Inside the Association, a daily show about basketball that he appears on as part of his deal with Stadium. If there was a predictable future for Charania, it was most likely an old one: TV. During the NBA season, he will spend much of the week in Los Angeles, where he will tape his cable show for FanDuel.

But in Chicago it was also clear that TV wasn’t driving Charania. He stepped into the bathroom before the taping and came back with his AirPods plugged back in, having squeezed in a quick call with a GM. In the studio, he asked a producer how to pronounce the name of the WNBA player he was interviewing and gamely read through a list of premade questions. Once the shoot was over, he picked up his phone and got back to work.