Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

What do survivors of human trafficking and gender violence need to help them move on with their life?

Sarah Symons

Sarah Symons started Her Future Coalition in 2005 with her husband John Berger. Since 2005 Her Future Coalition has been creating powerful and positive change in the lives of survivors of gender violence and girls at the highest risk.

They break the cycle of poverty and exploitation by providing education – and a full range of services that support education – to survivors and the most vulnerable girls in India and Nepal.

Previous to that, she was a composer of music for TV and film, and before that, a counselor and art teacher at Creative Arts Workshops in New York City.

Sarah is passionate about empowering survivors to be changemakers in their families and communities. She is the author of This Is No Ordinary Joy and co-author of the new book, Standing In The Way.

What We Discuss With Sarah Symons

- How she got started in helping survivors of human trafficking and gender violence

- How she chose what support services to provide survivors

- The root cause behind young girls being trafficked

- The difference between survivors who recover and move on and those who don’t

- Post Traumatic Growth and what we can learn from survivors

- How COVID has affected women’s issues globally

- The danger of staying silent

Transcript Highlights

How did you get started in helping survivors of human trafficking and gender violence?

It started in a very unexpected way. I had a very different kind of life back almost 20 years ago. I was working on Cape Cod, as a songwriter for film and television. My husband was an investment banker and our children were very small. One of my sons was featured in a film that was in Tribeca Film Festival.

I went to New York to see it and while there, saw this incredible documentary called The Day My God Died. It told the stories of young girls who had been trafficked from Nepal into the brothels of India. It really exposed the terrible suffering of that situation and the injustice they faced, even after they were rescued.

The part that was the most powerful for me was the inspiration of seeing all these people from around the world and different walks of life who were facing this issue down. Rather than being overwhelmed by the enormity of it, or avoiding the horror of it, they were taking action to help survivors and prevent girls from being trafficked. Some of the people in the film were themselves survivors who had been rescued and were putting their lives on the line to save others.

I thought there had to be something I could do to help and made the decision that very day to devote my life to working on this issue and to try and bring opportunities and a different future to those who had experienced it or who were imminently about to experience it.

How did you determine what services you were going to provide?

My biggest touchstone was to come at this from a place of humility recognizing that I did not have any expertise on this issue or international relations developed going into this, so I really needed to rely on the local organizations who were already doing the work and embedded in the communities, who knew best how to approach this.

The other primary value is collaboration. No one organization is going to combat human trafficking on its own. You need all kinds of solutions, ranging from legal solutions to more social work oriented, prevention, working with law enforcement, doing the rescues, sheltering the girls, and educating them. Rather than come in with a big ego like, “I know how to fix this”, you need to come with an attitude of, “What’s working and where can I add to this and be of service to make this work better?”

We reached out to local organizations, starting with the ones featured in the film. They asked us to work on economic alternatives and employment solutions for older survivors so we started there. By older I mean girls that had been rescued at age 16 or up, probably have almost no primary school education and may not want to go back to kindergarten and rejoin society that way. So they were looking for jobs that girls with low literacy, high trauma and high stigma could do.

We started there and over the years we grew and our understanding of what survivors needed evolved and changed. While we still work on the vocational training piece, we’ve added a lot of education programs, both for survivors and for their children, and for children who are either growing up in a red light area or a sister or mother has been trafficked, and they’ve been identified as extremely and eminently at risk. Finally, creating shelter and building on the shelters that are there so there’s a safe place for people to go right after they’ve been rescued.

What is the root cause of these young girls being trafficked?

I think we’ve all seen Hollywood movies like Taken which present a pretty unrealistic view of how this happens in 99.99% of the cases. In most cases it’s happening to young girls who already had some vulnerabilities. Poverty is a huge vulnerability, the death of a parent, parents that have addiction, and being a member of a minority or tribal group – this is the case in America as well as India and Nepal, that people from indigenous communities are extremely targeted. In America, kids coming out of foster care and kids of color are trafficked at a much higher rate than white kids from middle-class communities.

The other huge one is the low status of women in the community. This is especially an issue in the areas of India and Nepal where we work, where a girl’s birth is not celebrated and is considered burdensome. Because of the dowry system and other cultural issues, young girls are the least valuable members of society. So when things fall apart, that’s who bears the brunt of it. But in many cases, it’s not parents who sell their children. It does happen but it’s much less common.

More commonly the parents are tricked into thinking that their daughter is going to work as a maid but will also be able to go to school, send money home or have a good life. Or in many cases, girls at a young age go to a big city and they are cut off from their support systems and they get trafficked by new neighbors or a landlady, or something like that. In most cases, getting into a child marriage creates vulnerabilities for girls. Whether they are trafficked by their husband who just married her to trick her, or they move away from her support systems to a big city and she becomes very vulnerable.

Do you offer education to girls and parents around human trafficking prevention and what to look for?

Absolutely, it is so much better to prevent this from happening than to try and heal someone after it has happened because it’s so devastating on so many levels – physical, psychological and spiritual in every way. So we do a lot of prevention work, working with girls and parents, and along with that, providing some alternatives; making sure girls are in school.

What makes the difference between girls who are able to recover and move on and those who don’t?

We are very fortunate that, in the shelter homes where we work, the recovery rate is very high. And for the last 15 years I’ve been trying to figure out why that is. It’s a big focus of my first book – why do they have the capacity for joy and trust? Why, when they’re given tools they are able to use them and move forward while others are not?

While I don’t have a definitive answer, I think one thing is that there is community around them when they are rescued. According to the laws of India, they usually spent 2-5-10 years, depending on their age, in a rescue shelter. They are surrounded by peers who have experienced the same thing. So there isn’t a sense of isolation and they can see examples of girls who are moving forward.

Also culture is a factor. The South-Asian culture is an incredibly resilient culture. People are used to seeing a lot of suffering around them; it’s more out in the open. I think it was the Dalai Lama who said, “We’ve removed so much suffering from our society that we are unable to cope with the little bit that remains.”

So there’s a sense in Nepal and India of, “I’ve got to make my life work. There’s no safety net. There is no social service system that is going to support me beyond 18.”

There is still 3-4% who are not able to recover and remain in their anguish and trauma. It seems to be about having the ability to see that what happened to you is not who you are. Your abuse and victimhood is not your identity. A terrible thing was done to you but that’s not who you are. But if you’re continually reliving it, you’re just re-traumatizing yourself every single day.

Even in these really hard cases, there are breakthroughs. It’s about putting a really loving environment around the person, having excellent mental health services and addressing this holistically – you can’t just have talk therapy. What happened didn’t just happen verbally. The abuse came through your body so there needs to be healing that is more kinesthetic – with dance, art and ways that people can express that pain beyond just words. They may not even have words to express it.

(Listen for Anjali’s story and insight into the book she wrote with Sarah)

What is Post Traumatic Growth and how does one practically embrace that?

I believe it was pioneered by Martin Seligman at the University of Pennsylvania when he was working with soldiers who had PTSD. For every trauma that occurs in your life, there is a possibility to use it and find something from it. I certainly would never say that everything happens for a reason – I don’t believe that. But I do believe that you can make a reason, and you can make something beautiful out of the ashes of something terrible.

I wish Anjali had never been trafficked but those are the words she’s got to work with, and she says, “I’ve got to make a new story with the same words.”

What effect has COVID had on women’s issues globally?

It has been very hard on the most vulnerable. In Calcutta where we have a lot of our operations, there was a very strict lockdown. For two and a half months, you couldn’t leave your house except with police permission, and only to get food. Schools were closed, people did not have Wifi in order to have an online school experience, and schools have remained closed up until now. So a lot of kids lost an entire year of school, which is critical for girls like ours.

There was a risk of hunger and starvation and we and a lot of other non-profits switched direction really quickly and went into feeding and relief work, which is not what we do or our mission but it was necessary to keep girls from being trafficked.

For girls who had been trafficked, been locked inside was incredibly triggering and traumatizing. They felt like, “It’s happening again and I have no control.” It was very frightening and distressing. So we doubled down on the mental health services that we provide.

Again for domestic violence, for people who have an abusive family member, now they’re stuck inside with him all day long and there’s no escape. It was really hard, and I’m very hopeful that soon the schools will be able to reopen. Some of our centers in the red light district have reopened at a lower capacity because we just had to. Those kids live in a one-room brothel with their mother and when clients come, they need somewhere to be that’s not that one room.

What is the danger of staying silent about this issue?

I don’t talk about what happens, it’s obvious – a brothel where girls are seeing 10-12 men at night. Enough said. There’s no point to go into it because that’s likely to make people so overwhelmed and distressed that they back away.

Who was it that said, that all that it takes for evil to continue is for good people to do nothing – or say nothing? Human trafficking is an issue that thrives in silence, darkness and in shame. The more we are ashamed about it and keep it in the shadows and don’t talk about it, the more it can easily happen.

On the flipside, the more you expose it and shine a light on it, bring attention to it and intervene against it, it actually responds really well. It’s an issue that can be handled. Individual lives and communities have seen dramatic changes for the better.

There are so many wonderful people working on this around the world. I say join us, or if you can’t join us, donate, spread the word and use your voice, whether it’s individually or on social media to raise awareness.

The message I want people to share is not just that human trafficking is horrible and unacceptable, but also that you can do something about it and it’s an issue that responds really well to intervention.

Share with us some stories that have touched your heart the most and what you’ve personally learned from this journey.

There’s so much in that but I’ll try to be brief.

(Listen for Priya’s story and how she gained the opportunity to interview Michelle Obama and Malala Yousafzai)

I’ve learned so much and have been completely transformed by this experience. Every time I go to Calcutta or Nepal and I work in these shelters and areas, I come back and say, “I’m never going to complain again. I am so lucky and so blessed.” Of course I eventually complain again, but I keep it going for a good couple of months. I feel that it has given me an incredible perspective and hopefulness that I never had before.

If you can rise up out of that, anything is possible and we can transform our world through our love for one another into a heaven on earth. That’s all thanks to these girls and women, and what they’ve given me.

Episode Resources

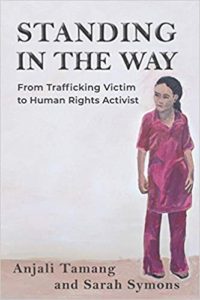

- Book – Standing In The Way: From Trafficking Victim to Human Rights Activist (Anjali Tamang and Sarah Symons

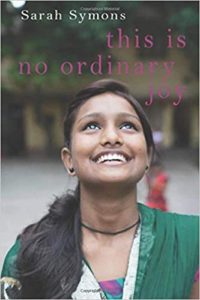

- Book – This Is No Ordinary Joy: How the Courage of Survivors Transformed My Life (Sarah Symons)

- Sarah’s TED Talk – Living Heroically

Learn More About Her Future Coalition and Get Involved

https://herfuturecoalition.org

Did You Enjoy The Podcast?

If you enjoyed this episode please let us know! 5-star reviews for the Leaders Of Transformation podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Pandora or Stitcher are greatly appreciated. This helps us reach more purpose-driven entrepreneurs seeking to make a positive impact in the world. Thank you. Together, we make a difference!

Additional Episodes You May Like

- 365: Changing Perspective with Nathaniel Brown

- 340: Chris Field: Disrupting for Good

- 314: Eva Yazhari: Bringing Hope and Finances to Rural India and East Africa

- 310: Wendy Steele: Empowering Women and Transforming Lives

- 119: Harmony “Dust” Grillo: Bringing Healing To Women In The Sex Trafficking Industry

- 033: Dr. Jenny Lopez: Women Add Value