New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

On Aug. 20, 1922, roughly 20,000 spectators gathered at a Paris stadium to watch women break records in events from the 60 meter dash to the 1,000 meters to the shot put. Headlines called it the Olympics, but this was no ordinary Olympic Games: track was only the only sport contested, and there were no men on the starting line.

Since 1900, women had been allowed to compete in certain Olympic sports—ones deemed “appropriate for women,” such as tennis, golf, and figure skating. Track and field remained off limits into the 1920s, when women tired of waiting decided to stage their own competition.

The women-only Games were “an important catalyst for persuading Olympic organizers that women were capable and deserving athletes,” says Jaime Schultz, a professor at Penn State University’s History and Philosophy of Sport program.

“I can’t imagine the fortitude it must have taken to go up against the IAAF and IOC, much less to establish popular and successful international competition,” she said.

RELATED: The Running Pioneer You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of

The French Connection

The event was organized by the Fédération Sportive Féminine Internationale—or, in English, the International Women’s Sports Federation—whose president, Alice Milliat, was a leader in the women’s sports movement in France.

Ainsi que la Française Alice Milliat (1884-1957) nageuse, hockeyeuse et rameuse, militante de la reconnaissance du #SportFéminin pic.twitter.com/nagdn85Qbz

— Laboratoire Egalité (@Laboegalite) May 5, 2017

In 1919, Milliat asked Olympic officials to let women compete in track and field at the 1920 Olympics at Antwerp; Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics and then president of the International Olympic Committee, was strongly opposed, said Florence Carpentier, senior researcher in University of Lausanne and a sports historian who specializes in Olympic history and gender history.

Two years later, the French women’s sports federation hosted an international competition for women in Monte Carlo, with about 100 female athletes competing from five nations—France, Great Britain, Italy, Norway, and Switzerland.

But athletics events (aka track and field) were outnumbered by gymnastic dance events that emphasized women’s grace, Carpentier said.

To Milliat, it seemed like a “euphemized” version of sport for women, Carpentier said.

In October 1921, the Women’s Sports Federation (FSFI) was established, with Milliat as its president. The FSFI staged a repeat of the Monaco event two years later and in addition created the Women’s World Games, which were first held in Paris in 1922.

RELATED: Can We Run Away From Politics?

Olympics History in the Making

The U.S., U.K., France, Czechoslovakia and Switzerland sent 77 athletes. It was the first time a group of American women represented the U.S. at an international track and field competition, according to American Women’s Track and Field: A History, 1895 through 1980 by Louise Mead Tricard.

Several of the U.S. athletes, selected at a handful of tryout meets across the country, were high school and college students, and many paid their own way, the New York Times reported.

Days before the team set said for Europe, during a two-hour training session in New Jersey, Coach Dr. Harry Eaton Stewart told the Times the American team was less experienced than the competition but “we will concede nothing, because we think we have a chance in every event.”

The competition aroused so much interest: French newspapers discussed athletes’ training tactics in the days leading up to the races, and more than 20,000 people filled the grandstands at the Paris stadium on the day of the competition, according to the New York Times.

Spectators didn’t have to wait long for records to start falling.

Mary Lines, of the U.K., set new world records in preliminary rounds of both the 60 meter and 100 yard dashes, only to see Marie Mejzlikova, of Czechoslovakia, sprint even faster to claim both the record and the gold in the 60 meter finals. Mejzlikova also took silver in the 100 yards, while Lines took bronze in that race and won the 300 yard dash.

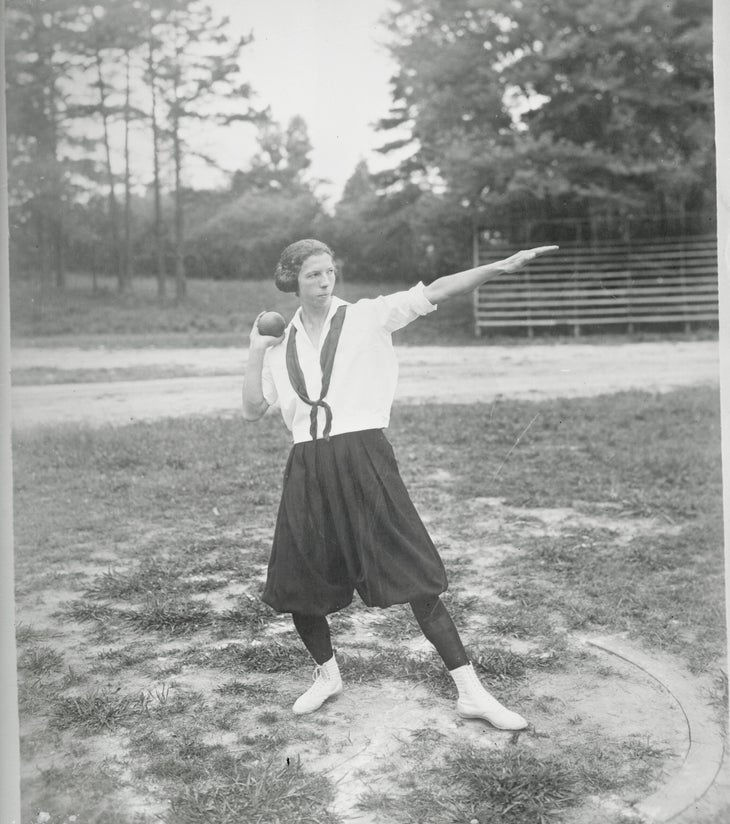

American Lucile Godbold, meanwhile, won the shot put with a world record throw, along with a bronze-worthy javelin performance.

Godbold, a student at Winthrop College in South Carolina who was chosen to be the U.S. team’s flag bearer, was nervous while preparing for her first event, the shot put, but heard her coach cheer before her record-setting throw, according to an account of her speech at a welcome home celebration in Mead Tricard’s book.

When photographers surrounded her after her win, “I grinned like a lunatic and tried to make believe I was used to it—but you know better,” she said.

Goldbold also competed in the longest race of the day, the 1,000 meter run, which was dominated by a pair of French runners.

Lucie Breard and Georgette Lenoir both finished at least 50 meters ahead of their closest competitor, and Breard set a world record, according to news reports. Godbold came in fourth after being tripped up near the finish when the runner in front of her fell.

“I could have murdered her. I was going pretty, and if somebody had offered me a million dollars to stop I could not have done it,” Godbold said at the celebratory event. She went on to teach physical education at Columbia College for 58 years.

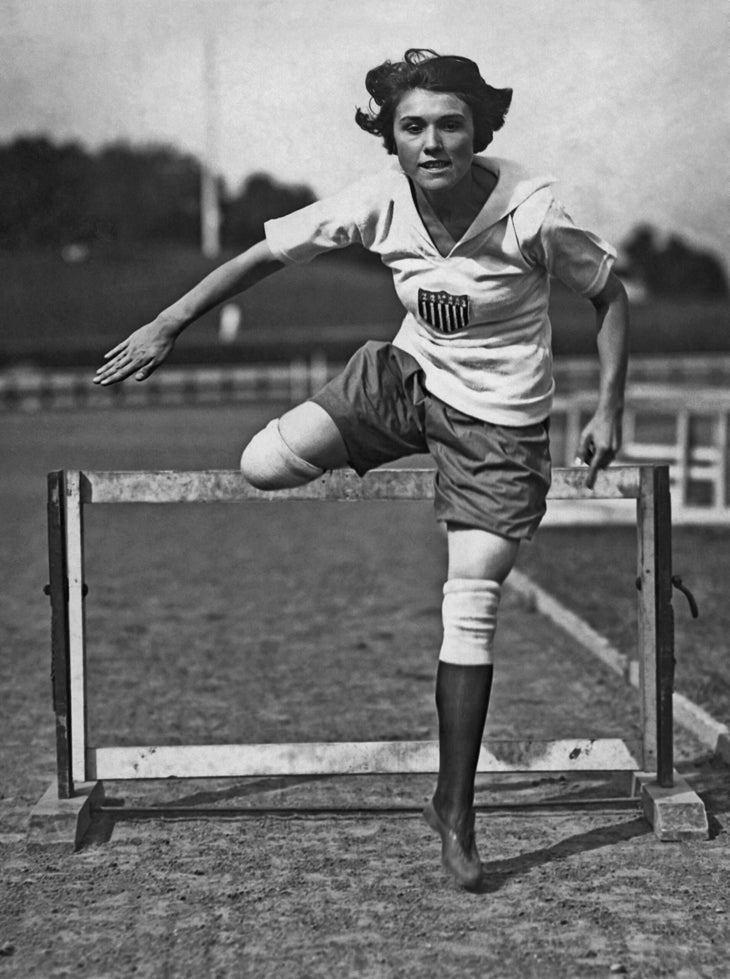

The U.S. team fared better in the 100 yard hurdles even though one of their top contenders, team captain Floreida Batson, sprained her ankle 10 days earlier in practice.

Batson, a Smith College student who began hurdling as a high schooler at Rosemary Hall, broke a world record in the prelims but struggled in the finals after her injured ankle gave way when she hit a hurdle.

“It was very disappointing,” she said while recalling the event years later, according to Mead Tricard. “But in Rosemary you were taught to take your disappointments and not say anything about them … We were taught to be a sports person and not cry over losing or anything like that.”

Instead, her teammate Camelia Sabie, a recent graduate of Newark Normal School, broke Batson’s record to take gold.

The British team, which also set a world record in the 4 x 110 yard relay, was deemed the winner in terms of points scored across the 11 events, followed by the U.S., then the French. Lines earned the most individual points, followed by Sabie and Godbold.

“The general impression is that the international games for women will prove a success, as a big crowd assembled today despite two counter attractions, the French athletic champions at Colombes and the swim across Paris,” the New York Times wrote.

Fighting for Change

While FSFI decided to continue holding the Women’s World Games every four years, Milliat still hoped to convince Olympic officials to let women compete in track and field on equal footing with the men.

And though Coubertin firmly opposed women’s participation, other Olympic and global track officials realized they “could not hold back the tide” and decided they were better off including women’s track than contending with a rival group, said Kevin Wamsley, a historian focusing on the Olympic Games and academic vice president and provost of St. Francis Xavier University.

“They want to get a handle on women’s sport, control it and dictate what happens,” he said.

They also objected to the FSFI’s use of the “Olympic” name.

Eventually, the FSFI and global Olympic and track and field officials negotiated a deal. Women would compete in track and field at the 1928 Games in Amsterdam, while the FSFI could continue holding its quadrennial women-only competitions as long as they dropped the “Olympic” name.

They were renamed the Women’s World Games until financial struggles forced a halt in the 1930s.

It would prove to be something of a double-edged sword for women. At the Olympics, the IOC and IAAF set the rules, and Milliat didn’t realize at the time how limited the roster of track and field events would be.

At the 1928 Amsterdam Games, women were allowed to compete in five track and field events, while men had 22. (There had been 11 events at the FSFI’s 1922 Games.) The longest race shrank from 1,000 meters to 800 meters.

That 800-meter race would end up threatening future competitive prospects after news reports focused more on the athletes’ exhaustion at the finish line than their performances.

The race “plainly demonstrated that even this distance makes too great a call on feminine strength,” a New York Times reporter wrote, even as he deemed it “one of the day’s most sensational races,” where six of nine runners finished under world record time.

Historians say press reports of athletes collapsing at the finish were wildly exaggerated.

Reporters may not have been intentionally trying to mislead readers, but their beliefs about women and sports influenced what they saw, said Victoria Jackson, a sports historian at Arizona State University.

“There’s a false narrative that develops out of that race that’s used to keep women out of strength and power events based on bad science, fake science and lies,” she said.

Women wouldn’t race the 800 meters at the Olympics again for more than three decades, in 1960 in Rome. It took 12 more years to add the women’s 1,500 meters.

The pattern of women creating their own athletic opportunities and running into resistance from or being folded into men’s organizations wasn’t unique to track and field, Jackson said.

Both Jackson and Schultz likened the story of the Women’s World Games to the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, founded to govern women’s intercollegiate sports in 1971 when the NCAA strictly concerned itself with men’s sports.

The AIAW at one point offered more championships for women than the NCAA had for men and was led primarily by female coaches and administrators, but when the NCAA decided to take on women’s sports, it offered college athletic programs incentives the AIAW couldn’t match and the organization eventually folded, says Schultz.

There’s a lot to be gained by joining powerful organizations like the NCAA, IAAF and IOC, but it also tends to mean losing organizations uniquely focused on women’s interest and women in positions of power. “We lose something when women lose control over their own sports,” says Schultz.

RELATED: 6 Life Lessons from the Pioneers of Women’s Running