I’ll spare you the poop jokes and get right to the point: endurance athletes tend to have a lot of gastrointestinal issues. The standard estimate is that 30 to 90 percent of marathoners and triathletes (i.e. somewhere between no one and everyone, much like running injuries) experience nausea, bloating, reflux, abdominal pain, flatulence, and diarrhea during their events.

None of these things are fun. But figuring out why they happen and how to avoid them has proven to be a formidable challenge. A new review in the European Journal of Applied Physiology gives a broad overview of what’s currently known about the topic, and highlights some promising areas of emerging research, like the gut-brain axis and role of hormones secreted in the gut. There’s no magic cure at the end of the article, but the authors—a team from several institutions in the United States and the United Kingdom, led by Florida State’s Michael Ormsbee—weigh the evidence on some possible countermeasures. Here’s the scoop.

What Goes Wrong

I should start by noting that, in general, people who exercise regularly have better gut health: less constipation, lower risk of colon cancer, and so on. But during prolonged endurance exercise, things can get uncomfortable. The longer and harder the exercise, the worse and more frequent the symptoms tend to be. In fact, that’s one of the problems with much of the existing research: if you have subjects jog for an hour, most of them don’t have any GI issues, so it’s impossible to tell if the miracle cure you were testing works. Future studies, the authors suggest, should involve exercise lasting at least two hours at a moderate effort of 60 percent of VO2 max or more.

The lining of your gut is where the problems start. It has two jobs: to let food pass from your gut into your bloodstream, and to prevent nasty bacteria and toxins from following the same route. During exercise, blood flow gets diverted away from your digestive organs, which normally take about a quarter of your blood, in order to supply your hard-working muscles with oxygen. Even moderate exercise reduces the gut’s blood supply by up to 70 percent. Keep that up for long enough, and the oxygen-and-energy-starved cells of the gut lining will start malfunctioning, blocking the food you’re trying to absorb and letting toxins leak into your bloodstream.

There are other factors that play a role. The bouncing and jostling of exercise may cause direct mechanical damage to the lining, which is probably why running causes more GI problems than cycling. Heat and dehydration also draw more blood away from the gut, making the lining more permeable. One theory for how heat stroke works attributes many of the symptoms to runaway inflammation triggered by toxins leaking from the gut into the bloodstream.

It’s not just a plumbing problem, though. One of the most frustrating facets of GI distress is that it’s often worst when the stakes are highest. Anxiety and psychological stress trigger the release of fight-or-flight hormones like adrenaline, which further diverts blood away from the digestive system and may also increase the leakiness of the gut lining. This is another reason the topic is so hard to study: you may be fine in training, fine in tune-up races, and fine in lab tests—but still end up in the porta-potty halfway through your big goal race.

The review also gets into some more nuanced mechanisms. For example, your gut produces a variety of peptide hormones that make you feel hungry or full, and speed up or slow down the passage of food through various parts of your digestive system, including by altering the permeability of the intestinal lining. These hormones are mostly produced in response to what you eat, but they also respond to exercise. So does your gut microbiome, which plays a crucial role in these digestive processes. The point: it’s unlikely that there’s one single cause for your digestive problems, which unfortunately means there probably isn’t one simple solution either.

How to Fix It

The most obvious approach to dealing with GI problems is to consider what you eat. In a perfect world, you’d identify a few foods that trigger your problems, eliminate them from your diet prior to races, and then you’re good. When I asked Tour de France star Mike Woods a few years ago about what he eats in the days leading up to a race, he described his approach as a “5-year-old’s diet”: no veggies, no red meat, no high-fiber foods, in order to reduce bloating.

But there’s no real consensus about which triggers to worry about. Candidates include gluten and, more recently, FODMAPs, a class of poorly digested carbohydrate found in wheat, milk, stone fruit, legumes, and a variety of other foods. In addition to specific foods, timing matters: taking in fat, protein, or fiber in the 90 minutes before exercise may raise your risk of GI problems. These approaches are worth a try, but it’s also worth bearing in mind the downsides of unnecessary dietary restrictions. People following low-FODMAP diets, for example, tend to develop less healthy and diverse gut microbiomes.

Another option is supplements—and this is probably a good time to note that three of the review’s five authors report receiving research funding from companies that manufacture supplements. Still, their summary of the literature isn’t all that effusive. Studies generally seem to fall into two categories: those that find improvement in physiological markers like gut leakiness but don’t see any reduction in GI symptoms, and vice versa. The biggest focus of research has been on probiotics, and on balance I’m tempted to conclude that they work (in the sense of producing a mild improvement, not eliminating symptoms entirely). But the devil is in the details: which strains of probiotics, in what combination and quantity, for how long?

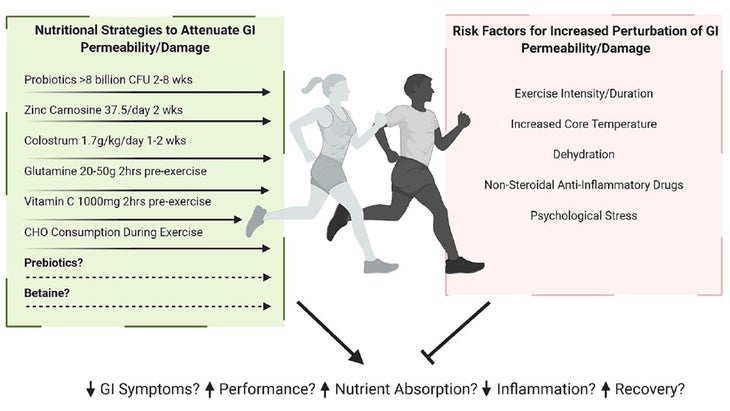

The review includes the handy figure below which shows, on the left, a list of supplements that may help with exercise-induced GI function, along with specific dosage recommendations. With the exception of probiotics, I don’t find the evidence for any of them convincing—but it’s a very hard topic to study in the lab, so I can’t rule it out either.

If there’s one fix that seems most promising, it’s the idea of training your gut. There’s plenty of anecdotal evidence that, over time, athletes get used to downing sports drinks and gels with fewer and fewer GI symptoms. There’s also some mechanistic evidence showing that the gut lining develops more transporters to ferry specific nutrients into the bloodstream if you eat them regularly. And, as I wrote a few years ago, there’s practical evidence that even just two weeks of gut training can measurably improve GI symptoms during a long run.

That seems like an optimistic note to end on. But let’s be honest: there are many athletes who’ve been struggling with gut issues for years. Regular exposure hasn’t solved their problems. For them, the best option is to painstakingly and methodically work through as many potential causes and solutions as they can. For starters, I’d recommend picking up a copy of Patrick Wilson’s 2020 book The Athlete’s Gut: The Inside Science of Digestion, Nutrition, and Stomach Distress. Wilson, too, doesn’t offer any miracle cures—because he’s not full of crap.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.