A new coronavirus variant – A.30 – has been identified by a group of German researchers as highly-efficient in escaping vaccine-induced antibodies. However, since only four cases of the variant have been recorded in the world, none in the past five months, the variant is most likely already extinct and there is no need to be overly concerned about it, said Prof. Cyrille Cohen, the head of the immunology lab at Bar-Ilan University.

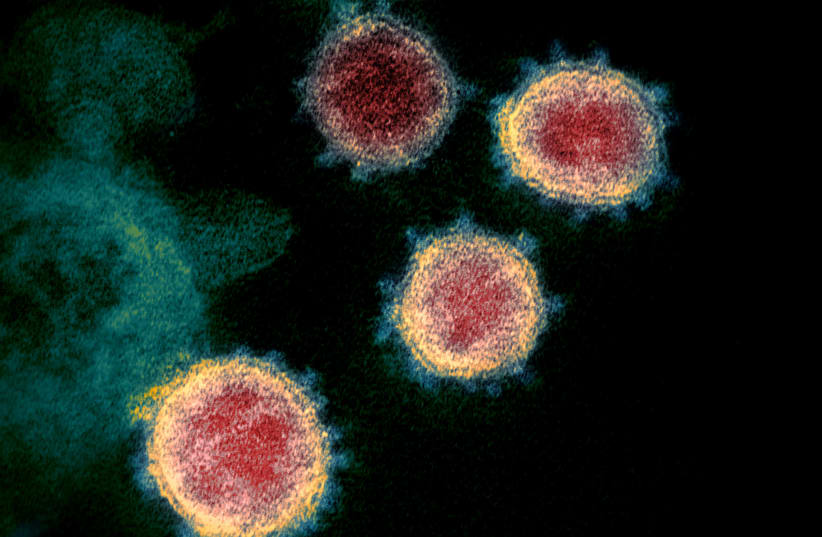

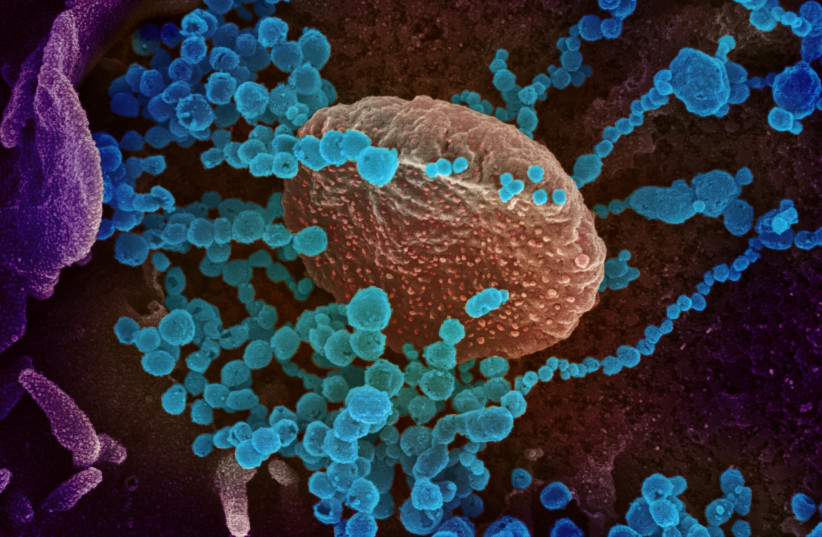

Viruses constantly mutate. While most mutations have no consequences, a cluster of mutations can engender a new variant, and the virus may create a different protein as a consequence. In the case of the coronavirus, the key protein to consider is the spike protein, which is found on the surface of the virus and allows it to penetrate host cells and cause infections.

According to the study published in Nature, the A.30 variant probably originated in Tanzania and was detected in individuals in Angola and in Sweden. It presents significant mutations in the spike protein, which the vaccine produced antibodies target.

However, Cohen said that there are several reasons why the variant does not appear to be a threat, even though studying it is important because it might help understand how its mutations work if they appear in other variants in the future.

“It could be that a variant can evade the immune system in the lab but it cannot spread fast, it does not infect a lot of people and therefore it disappears,” he said.

This seems to have been the case for A.30.

“It is possible that some of its mutations will reappear, but we have not seen a case of it since May,” Cohen noted.

He explained that when it comes to a new variant there are three elements to investigate: whether it spreads fast, it causes a more severe disease, and it evades the immune system’s response.

“With Alfa, Gamma and Delta variants we know that vaccines are effective,” Cohen said. “In July we were asking the question whether the spike of cases in Israel was caused by the fact that it was more contagious, or that it was resistant to the vaccine or because the immunity was waning. Now we know that it was more contagious and the immunity was waning, but a fresh vaccine was still highly effective against it.”

On the other hand, the family of the Beta variant – also known as the South African variant – appears to be more resistant to the vaccine but it has not spread in the world as much.

“So far, we see that the Delta and its descendants are the variants causing problems in the world,” Cohen concluded.