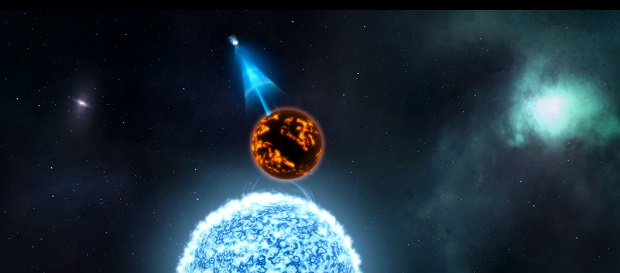

Wot I Think: Stellaris

Supergiant or electroweak?

Stellaris [official site] is one of the most eagerly awaited strategy games in years. Known for their historical grand strategy games, Paradox Development Studio have turned their attention to the stars, with a game that attempts to create a sense of sci-fi mastery through its randomisation of everything from the galactic map to the traits and behaviours of individual species. But in marrying traditional 4X systems to the complexities of their previous offerings, have Paradox found a fine balance or a series of compromises. Here's wot I think.

Stellaris is a true hybrid. Throughout its design, the threads of 4X games are stitched through the tapestry of Paradox's patented grand strategy style. In that, it's a success, intelligently recognising which elements make for happy shipmates and jettisoning the rest into the void, or reconfiguring them to find a happy middle-ground. It's the company's most elegant and accessible strategy game, with an interface that while not far removed from the likes of Crusader Kings II or Europa Universalis IV, has undergone a nip and tuck to hide unnecessary complications and direct the eye (and the mouse pointer) toward what is essential at any given time.

It's tempting to assume that if you're interested in Stellaris, you already know what to expect from a 4X game, and how that might differ from a grand strategy game. Perhaps you've been brought here by the lure of dynamic science fiction stories rather than taxes and trade though, and if that's the case here's a quick primer on what Stellaris seeks to achieve, and for those in the know, I'll begin to explain how well it all works.

4X games take their name from the central activities that make up playtime: eXploring, eXpanding, eXploiting, and eXterminate. From tiny beginnings, your chosen nation/faction/race explores the world, starting with their immediate surroundings, builds new settlements to expand, exploits the resources that they find and the relationships that they nurture, and exterminates anyone who gets in the way. The balance between the four Xs depends on your playstyle and the particular situations you find yourself in, but the general shape of such games tends to involve uncovering the map from behind a fog of war, and then painting it red/blue/green/yellow/fuchsia.

Stellaris follows that formula but upsets the march toward domination with several tricks borrowed from the less predictable and linear shape of Paradox's grand strategy games. You begin with a single planet, your species' home world, and most other players are in the same position. Faster-than-light travel is a new discovery and you're likely to spend the first stages of the game exploring your own system, searching for exploitable resources on nearby planets and moons as you prepare to head out into the galaxy.

Even before the game proper begins, your choice of FTL technology determines how you'll explore. You can choose between three possibilities - hyperlanes, warp or wormholes - and each fundamentally changes the way your experience plays out, from beginning to end. A game played with hyperdrive tech can see you bottled into a corner, with dead-ends and angry amoebas all around, while working with warp or wormholes is initially liberating but has its own drawbacks.

Whatever your FTL choice, science ships will undertake most of your early exploration. They're a combination of scout and research vessel, able to survey new systems to tag resources while also discovering anomalies to investigate. Those anomalies and other discoveries mark one of the larger most obvious interruptions to the traditional shape of a 4X game.

Some are little more than the interstellar equivalent of Civ's goody huts, providing a boost to resources or research values, but even those lesser events are elevated by the quality of the text that introduces them. One of Stellaris' great strengths – strange to say for a strategy game – is in the writing. From the humour of the diplomatic messages that encapsulate ethical stances in tidily composed sentences to the longer event chains, and the mysteries and wonder they contain, Stellaris does flavour text so well that it becomes plot.

It's the best-written strategy game since Alpha Centauri, drawing in ideas from almost every strand of science fiction and giving them space to add colour and interest to the galaxy. While the simplest discoveries play out like goody huts, the more complex event chains are almost reminiscent of Sunless Sea's stories, with various avenues of possibility, and outcomes that are restricted by and later inform the character of your empire and founder species. It's in these that the game finds the sweet spot between its strategic systems and its urge to tell every sci-fi story under/in/around every sun.

This is nowhere more apparent than in the late-game crises. These are not so much 'event chains' as 'event bombs', blowing the game wide open by introducing new dangers and tearing empires apart. They're triggered by the activities of players, both AI and human, with an element of randomisation to determine if and when they begin. Certain elements must be in play before the genesis event for a particular crisis begins and even then, they can be defused. Strategy games may be built on a foundation of numbers but one of Stellaris' great strengths – not unexpected given its pedigree – is to elevate words to almost equal importance.

Let's talk numbers though. The purpose of the crises and other event chains, including the pre-sentient and pre-FTL species that can be discovered across the galaxy, is to add wrinkles to the natural progression of a 4X game. The same is true of Fallen Empires, which are bloated, powerful but stagnant AI entities, each with their own personality type. All of these things interrupt the march toward victory, either by placing speedbumps in the road or – far more intriguing – providing alternate routes. Rather than navigating a path that leads toward victory, avoiding obstacles and taking advantage of speed boosts, you're exploring possibilities. Sure, you can ruthlessly exploit and exterminate in a way that isn't always feasible or satisfying in CK II or EU IV, but even though there are victory conditions to achieve, the game encourages you to take the scenic route. There is almost as much value here for sightseers as for those wishing to soldier toward dominance.

Despite all of the plotting and the diverse range of species you'll encounter, Stellaris is relatively transparent when it comes to the numbers. There are three basic resources, two of which are mined from the map and one that stems from your status and control of your population. The physical resources – energy and minerals – are, respectively, a form of galactic currency and the war material from which ships and planetary improvements are constructed. In simple terms, minerals help to build the foundations of empire and energy ensures that the lights don't go out.

Both of these resources can be detected on planets and in stars through use of survey ships. Ideally, you'll want to build a mine to suck up every item within your empire's borders and the galactic map does a splendid job of highlighting precisely what is available in every system, and whether a construction ship has already built the necessary facility to take advantage of the bounty. Until matters become complicated by conflict later in the game, the shiny green numbers next to your mineral and energy stashes should be ticking upwards at a steady rate.

You won't have to worry about inflation or exchange rates or the cost of shipping minerals from the homeworld to a distant outpost. If the numbers are going up, you can spend the resources as they arrive and not worry too much about where the next batch are coming from. As a game of resource management and exploitation, Stellaris is extremely easy to come to grips with, and even when new tech unlocks rewarding strategic resources to capture, capturing and utilising them is a simple case of controlling the correct system and building a facility to extract them.

This feels like the right choice for a game that is more interested in the complexities that arise within an empire than the basic infrastructure of that empire. From the very beginning of a game, whether you decide to craft a species and government or play with a random creation, Stellaris places you in a very specific role. You'll be assigned, or select, a handful of traits - both negative and positive - that define your species. There are only a few negative traits at present, which prevented me from trying to take a pile of idiotic jellies into space, and ethics aren't classified as either positive or negative. They simply permit/forbid certain behaviours. Are you a xenophobic democrat terrified of every shadow you see in space or the ruler of a pacifist race of religious fanatics? Would you prefer to build a galactic federation of peacekeepers or an ugly alliance of convenience, ready to shatter as soon as the knives grow long enough?

Every choice comes with certain restrictions. Certain ethical codes will prevent you from enslaving members of your own race, which can speed production while reducing happiness, while others will prevent you from making certain decisions during event chains. Everything from the migration of people within the galaxy to the level of orbital bombardment that can be used to soften up defenses prior to a planetary invasion is determined by the outlook of your species. In that sense, Stellaris forces you to roleplay, creating boundaries that cannot be crossed, and the people who get the most out of the game will be those who take that roleplaying ball and run with it.

Because the characters who take up positions within your empire aren't as numerous or as convincingly fleshed-out as those in Crusader Kings II, Stellaris has much less scope for the kind of interpersonal stories that make that game such a delight. A scientist exploring the fringes of the universe, and the fringes of knowledge, might gain new traits as a result of her experiences, but she won't have a family to care about back at home. Leaders provide bonuses based on their own traits and different government types have different rules for when the top job changes hands, but the only personality on show is for a species as a whole rather than for the individuals within that species.

From a diplomatic perspective, that makes the game much tidier. You're dealing with a type of negotiator rather than one person bringing their own motivations to the table, interlaced with the needs and fears of an empire. This is a trend that runs through the whole game – it's neat, legible and compact. Sure, it's “grand strategy on a galactic scale” just like the tagline says, but Stellaris is a game that shows its hand at all times. There are surprises, both pleasant and perilous, but it's possible to keep track of and account for every element in play at any one time. Compared to the rich complexities of its Paradox predecessors, that may make Stellaris seem either disappointingly anaemic or exquisitely lean depending on what you want from the game. While there are certainly areas that I find a little too thin, I find the overall structure an almost perfect fit.

In terms of the game's systemic integrity, the clarity of statistics and interactions means that everything is on show. Want to know why those molluscoid militants won't agree to peace? The game can break it down for you in a way that is almost immediately comprehensible, and you'll be able to figure out what steps need to be taken to change the situation. Noticed a sudden shortfall in your energy output? Hover over the resource bar at the top of the screen and a tooltip will explain all (you've almost certainly got too many ships in fleets that aren't locked in expense-saving orbit).

Combat is the one area where the game stumbles slightly in this regard. Every individual ship has its components and size translated into a single number, conveying military strength. A fleet has an overall strength derived from the sum of its parts. However, there are complexities behind that number that might cause an apparently superior fleet to come a cropper.

First of all, you're going to lose some military strength every time the enemy destroys one of your ships. That means a single ship with a military strength of 1k has an advantage against twenty ships with a combined strength of 1.2k – that second fleet will become increasingly feeble as the battle progresses, whereas the 1k ship effectively operates at 100% efficiency until it falls to pieces. Further to that, the military strength doesn't take into account components that might have been put in place to counter a specific threat. Weaponry divides into three basic types – lasers, projectiles and missiles – and certain defenses work better against certain offense. The military strength of a fleet gives a rough estimate of how they'd cope in an even battle, but battles aren't always even. And because conflicts actually play out on the map – and look rather handsome as they do so – there's at least a small element of simulation. Slow moving ships will struggle to close the distance which could be a problem if they don't have long-range weaponry.

All of which is to say, relying on the military strength reading and the “auto-best” option for ship construction and upgrades can lead to disaster. Adjustments are easy to make on the ship design screen - and the ability to simply click a button to automate the process of returning to the nearest spaceport and upgrading is a godsend – but I've spent a great deal of time building fleets and often feel that their success comes down to the luck of the draw somewhat. If I don't have the right tech to punch through an enemy's shields quickly, military conquest becomes much more expensive and time-consuming.

Tech doesn't entirely come down to the luck of the draw though. Research is the other area of the game, alongside combat, that threatens to muddy the waters of clarity. Conducted in three areas, tech research provides new options whenever current work in each area has been completed. The new options are randomised, though with weighting to provide a greater portion of 'cheap' tech, lower down the 'tree'. Occasionally you'll see a rare piece of tech or a costly invention that feels like it should come much later in the game.

Usually, there are three choices but you can open up more slots, either by performing research on the actual map – picking through debris or pieces of dead aliens to discover components and biological info – or by discovering technologies that provide extra slots. At first, the whole system feels like drawing from a trick deck of cards, rolling with whatever might emerge and hoping for the best. However, you can trick the deck even further by switching around the scientists in each department.

Intuitively, you'll stick scientists who can boost a particular branch of research to work where they're most obviously useful. But consider swapping the xeno expert in your biology labs for someone with a passion for military tech and you'll increase your chances of picking out certain types of card (virulent horror-weapons, most likely). It's one of the few areas in the game where you can push the numbers in your favour, trying to shape the future somewhat, without directly seeing those numbers. Opaque, where so much is transparent.

Thematically, most of these choices make perfect sense to me. The muddle of historical politics and personalities has been replaced by a more monolithic view – the present, for these spacefaring civilisations, is knowable; the future is not. That's why the mysteries and wonders of Stellaris so often exist at the edges of what is known: in the tech screen and in the extra-dimensional terrors or spiritual awakenings of the event chains. It's a 4X game that leans heavy on the exploration and exploitation, asking what you will find and how you will choose to deal with it rather than how many new worlds you want to conquer, even if many campaigns will end in intergalactic warfare.

And it's brilliant. I'd expected something messier and sometimes the edges are a little too clean and tidy, without the room for chaotic simulation that is such an integral part of Crusader Kings II. Stellaris is far closer to its 4X inspirations – Sword of the Stars, Distant Worlds, Ascendancy etc – than it is to Paradox Development Studio's historical grand strategy titles, but it's been carefully constructed so that there is room for growth in certain areas. Diplomacy and politics both feel like satisfactory foundations rather than fully-fledged systems at present, and the nature of the event chains opens up all manner of possibilities for new stories.

I say that I'd expected something messier and part of me had hoped for something messier. That messiness may come with expansions and DLC, but for now Stellaris is incredibly assured and confident, if perhaps a little too tidy and streamlined. It's one of the most accomplished 4X space games I've ever played, but it feels knowable. Despite all of the randomisation and the extraordinary influence of Fallen Empires and other features that shake the 4X formula hard enough to make it wobble, this is a game that can be understood, analysed and mastered. Doing so has been, and will continue to be, a joy, and yet I crave the early days of exploration before the galactic map became a place on which to exterminate the competition rather than to find new ways of living.

The great experiment of the game was not so much the change of scenery, from history to science fiction, it was the decision to create a Civ-like game of expansion with some complexities and aspects of simulation borrowed from grand strategy. It's in the simulation of a living galaxy that most of the complexity has been lost, but what has been gained is a precise and finely tuned machine. Less erratic and surprising than its ancestors, but much more elegant in its design.

Stellaris is out today, 5pm UK time.